Winston Churchill once famously remarked, “Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” But the Soviet Empire was obviously not the only mystery that concerned politicians and the public in Cold War America and the larger “free world.” There was also Mao’s China. Inaccessible because the Chinese revolutionary state barred westerners from visiting the country, unfathomable due to the lack of direct contact and credible intelligence, “we’ve only fitful glimpses of what happened,” Pulitzer winning journalist and historian Theodore White so poetically put in 1967, “snatches of photography, so tantalizingly incomplete, to explain what happened.”[1] In a land of timeless tradition and “changeless wonders,” White proclaimed that China “began in mystery, and goes on today in mystery.”

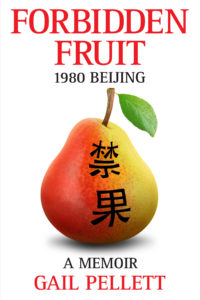

The mysterious qualities of China perpetuated two opposing but interdependent patterns of representations of the country and its people in Western political and popular discourses during the Cold War. One depicted China as a nightmare of red menace, fueled by xenophobic tradition and revolutionary madness, threatening to destroy everything the “free world” stood for. The other promoted a rosy picture, showing China as a dream of utopian future that held the promise for the global fight against all forms of inequalities and exploitations. While the “Red China” nightmare galvanized anti-communist politics in the escalating Cold War, the utopian dream took roots on western campuses and intellectual circles and bred a generation of New Leftists in the West. It was against this backdrop of ideological standoff and political agitation in the 1970s that Gail Pellett, author of this book, began her intense and intimate encounter with China.

In her own words, Pellett “had been influenced profoundly by the ideas and slogans of that [China’s] revolution and its egalitarian, anti-authoritarian, anti-bureaucratic thrust, its effort to overthrow elites and elevate the power and wisdom of the underclasses.”

In her book, Pellett does not shy away from her deep, and sometimes naïve, infatuations with the Chinese revolution that she developed in her formative years in San Francisco as an anti-war and feminist activist, going from St. Louis to Berkeley as a student studying the family revolution in China, and then to New York City as a radio and TV producer. In her own words, she “had been influenced profoundly by the ideas and slogans of that revolution and its egalitarian, anti-authoritarian, anti-bureaucratic thrust, its effort to overthrow elites and elevate the power and wisdom of the underclasses” (372). As Pellett crisscrossed the United States in search of her political passion and professional career, the world began to change.

Political radicalism was winding down on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. More notably, Mao died and his radical allies—the Gang of Four—were purged in 1976. Deng Xiaoping launched the economic reform in 1978. One year later, China normalized diplomatic relations with the United States, which had been vilified for decades as the greatest enemy to the Chinese revolution. China’s powerful propaganda system began to educate people on these new visions of domestic development and the world order. The old slogans such as “class struggle” and “world revolution” were either significantly tuned down or completely removed from newspaper headlines; in their place were new policy initiatives to open and modernize China. Westerners were once again allowed to come to China. Foreign journalists came to open news bureaus, capitalists to set up joint ventures, and “experts” (zhuanjia) to help China with a multiplicity of tasks ranging from operating machines in factories to the reform of language curriculum in colleges. At this historical moment, Pellett was offered an opportunity to work for Radio Beijing, which was China’s equivalent to the Voice of America, to provide training in Western-style journalism. She took the offer, packed up, and came.

Her experience reveals that, for a westerner, to come and work in China in the 1980s was not an easy matter. It required an invitation letter, a Chinese host institution, a visa, an air ticket, and a person who could put all these pieces together, and last but not least, a willingness on the part of Pellett to explore the unknown. She had all.

Like many westerners of her generation who seized upon the opportunity to come to China in the wake of Deng Xiaoping’s historical economic reform, Pellett saw a country in transition and thus full of contradictions. Her experience reveals that, for a westerner, to come and work in China in the 1980s was not an easy matter. It required an invitation letter, a Chinese host institution, a visa, an air ticket, and a person who could put all these pieces together, and last but not least, a willingness on the part of Pellett to explore the unknown. She had all. Once she landed in China, Pellett found that living in post-Mao Beijing and working in a Chinese government agency was far more challenging than she ever anticipated. First of all, China at the time was very much an impoverished third-world country in terms of economic development and material life. She noticed:

“On the ground at the capital city airport of the world’s most populous country, there seemed to be less technology than at the Provincetown airport on Cape Cod. A dozen workers in grey, baggy overalls squatted in the shade of a sleeping jet, bicycles parked nearby. Chopsticks flew between mouths and metal boxes. The ground crew that flagged in our gigantic aircraft made frenetic arm movements, then stood with their fingers in their ears (10).”

At her apartment, household appliances, such as a television, washer and dryer, and modern communication devices like a telephone, were beyond her reach. Basic western foods, such as cheese and jam, were only available at the foreigner-exclusive Friendship Store about six miles away, or a 50-minute bicycle ride (one way) from where Pellett lived. Moreover, every time she cycled on the streets, she found herself surrounded by the monolithic and dreadful socialist scenes: men and women dressed as inconspicuously as possible in the iconic charcoal-grey “Mao suit,” “rows of four-story socialist Realist buildings (23),” and “giant images of Mao, Marx, Lenin, and Stalin stuck in bold on the front facade” of the Museum of the Chinese Revolution in Tiananmen Square (37). The omnipresent socialist sights, and the simple, and even Spartan life, characterized the monochrome of the social landscape of post-Mao Beijing.

While material life was simple, the Chinese way of handling foreign visitors and sojourners were depressing and even repressing. Like all foreigners in China, Pellett was required to live in foreigner-only compound, not to mingle with her Chinese co-workers or ordinary Chinese. Next were travel restrictions. Going anywhere beyond the capital city’s perimeters would require permission from her host institution and the itinerary must also be evaluated and approved. Moreover, it was almost impossible to ward off the prying eyes of coworkers sharing office desks, janitors cleaning apartment floors, and security guards behind the gate of apartment compound. There was “the total lack of privacy” (229). Worst of all, Pellett felt trapped in a comfortable cocoon made for her by her Chinese host. She was given a better salary, a bigger apartment, and access to stores reserved exclusively for foreigners. On the other hand, she was not allowed to meet freely with ordinary Chinese whom Pellett hoped to understand and befriend. “I could never seem to move beyond a surface veneer to something more authentic, reflective or revealing of private doubts and fears, fantasies and phobias or joke, that become the stuff of intimacy or true sharing” (70), she once complained.

To penetrate the invisible wall separating her from ordinary Chinese, Pellett devised many means, some conventional while others quite risky: organizing reading group for her unit, hosting holiday parties, buying cooking oil at the Friendship Store for Chinese co-workers and editing their application letters for American universities, organizing dance parties, and even secretly pursuing romantic relationships with Chinese. However, her attempts to crack government surveillance and to forge durable relationships with Chinese ended in utter failure. She protested at one point:

“There was no one with whom to share the experiences. Nobody to bounce off the insights, nobody who would laugh, cry or wonder with me. Nobody to question my interpretations. Nobody to linger with over a meal at the end of the day” (284).

Unable to overcome “the trauma of living with the surveillance, mistrust and fear that reinforce it (74),” and refusing to subject herself to the system and institutional culture that encapsulated her, Pellett quit her position at Radio Beijing and returned to the United States “with a broken heart wrapped in a blanket of depression (369).”

If she came to China aspiring to better grapple with the legacy of Mao’s revolution and understand the experimental phase of Deng’s reform, Pellett failed. She failed to unlock China’s past and present in part because of communication barriers. Not speaking Chinese herself and segregated living arrangement, both deprived her of many invaluable opportunities to have sustained discussions and meaningful conversations with the Chinese. But her experience also testified to the formidable power of Chinese state that “created a fearful, anxious state of mind” and “a self-censoring populace” (319). Even though the worst excesses of the Mao era’s political purges and mass campaigns had abated, the country and its people were still living in the outsized shadow of Mao, one of the most charismatic, complex, and controversial politicians of the 20th century.

Today, thirty-seven years after Pellett’s first trip to China, most historians agree that the experimental phase of the reform era is indeed a fascinating period. China arrived at the crossroads; or in historian and the President of the American Association of Asian Studies Timothy Brook’s words, this is a time of “strangeness” when “few foreigners lived in Beijing and no Chinese could be sure which way was forward.”[2] Travelogues and memoirs written by foreign visitors vividly capture this historic moment of confusions and contradictions. There are bitter memories of Mao’s revolutionary violence. There are also complaints about all kinds of bureaucratic restrictions and harsh reports of post-Mao state’s relentless attack on the budding democracy movement and draconian efforts to carry out the One-Child policy.

Even though the worst excesses of the Mao era’s political purges and mass campaigns had abated, the country and its people were still living in the outsized shadow of Mao, one of the most charismatic, complex, and controversial politicians of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, there are visible signs of change lurking beneath the surface stability of socialism. Pellett took notice of the pervasive street trade, “the shoe repairmen with their little stools, simple implements and jagged pieces of grungy leather, the tin man shaping useful items from recycled metal, the old woman who parked her sewing machine near the curb to mend those plastic zippered tote bags everyone carried” (66). Beyond the capital city, many westerners were surprised and thrilled to see similar instances of grassroots entrepreneurship. For one example, Baltimore Sun’s correspondent Michael Parks visited a village in central China and captured an amusing sight of farmers loading “little piglets on the back of the bicycles going off to the market” and selling them to make tidy profit and buy other consumer products.[3] These street trades underscored the dramatic shift of China’s economic policy and a bold attempt to dismantle Mao’s utopian program: the people’s commune was broken up, the free market was re-established, prices were deregulated, and people were encouraged to get rich. Over time, this “tiny stirrings of private enterprise” (66) mushroom from “tentative experiments of Deng’s Four Modernization at the grassroots level in the early 1980s to become the driving force that integrates China with the global market and contributes to the Chinese economic miracle that stuns the entire world.”

Working and living in China for seven months, Pellett took many snapshots of the country and recorded many slices of Chinese life; nonetheless, she was unable to piece them together into a complete picture and coherent story. But, Pellett’s “failure” captures precisely the essence of China in transition, emerging from revolutionary devastation and hesitantly embracing the uncertain future. The country contains multitudes, as every country does. It is in such a jumble of incomplete pictures and incoherent stories that we remain in search of the dynamism of China’s great economic reform.