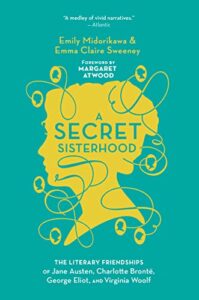

A Secret Sisterhood: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf

In A Secret Sisterhood, authors Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney make the bold claim that they have unearthed literary friendships which “a conspiracy of silence has obscured” (263), although it is hard to imagine how their research could uncover “a treasure trove of hidden alliances,” (xvi) considering the fame of the writers in question. We have reached the stage, after all, when the enthusiasm for all things Austen has led to the publication of Jane Austen for Dummies. The Brontë Society has been following every lead and preserving every scrap of information about that famous family since 1893. My quick count of biographies of George Eliot, including this year’s entry by Philip Davies, comes to a conservative fifteen, and biographies of Virginia Woolf to twelve and counting. That tally does not even take into account the published volumes of correspondence and diaries written by these authors and by those who knew them, or the popular blogs, author society journals, and academic scholarship which have chronicled their every association.

A Secret Sisterhood is framed by an introduction and an epilogue by the authors celebrating their own friendship, and their intention in pursuing as their chosen theme, “to learn valuable lessons about how we could sustain our own friendship in the years to come” (xix). A generous preface by Margaret Atwood attests to another act of sisterly encouragement. Though I I feel rather churlish in dismissing this declaration of intent as a guarantee of value, the appeal to the personal and anecdotal as both the occasion and the purpose of an exercise in popular biography seems calculated to package as fresh what is essentially a fairly stale bill of goods. Secret Sisterhood offers little in the way of secrets and even less in the way of female literary friendship, but instead rehashes what is already known in a form that hints at more significance than it can reasonably assert.

Though I feel rather churlish in dismissing this declaration of intent as a guarantee of value, the appeal to the personal and anecdotal as both the occasion and the purpose of an exercise in popular biography seems calculated to package as fresh what is essentially a fairly stale bill of goods.

A Secret Sisterhood proceeds on the basis of three related assertions which provide the rationale for the volume. The authors argue that women’s literary friendships have been neglected by biographers and literary historians while men’s friendships, such as those between Byron and Shelley, Coleridge and Wordsworth, have become legendary. They contend that the friendships on which they have focused—Jane Austen and Anne Sharp, Charlotte Brontë and Mary Taylor, George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe, Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield—insofar as they have been mentioned at all, have been misconstrued as either unimportant, unduly contentious, or “tantalizingly consigned to the shadows” (xx). And finally, Midorikawa and Sweeney assert, in order vigorously to refute the charge, that these authors have become ensconced in the popular imagination as “solitary eccentrics or isolated geniuses” (xiii). None of these claims holds up well under closer examination, nor do the chapters that elaborate them convince one to the contrary. The authors are repeatedly obliged to speculate where there is no evidence, to exaggerate influence when there is little to go on to corroborate it, and to present as “little known” (xvi) what is widely available information. The section on Jane Austen’s friendship with Anne Sharp, the governess of Austen’s niece Fanny, for instance, is almost entirely based on conjecture. The narrative of their connection is filled with such locutions as, “Anne might well have hoped”; “she must have grown anxious”; “she and Anne would have found plenty of opportunity for literary conversation” (12, 15, 19). Charlotte Brontë’s letters to Mary Taylor, the friend on whom she based the character Rose York in her novel Shirley, were burned by Taylor, just as Katherine Mansfield burned the letters that Virginia Woolf sent her. Unfazed, the authors make much of the literary influence of Taylor on Brontë (she did not like Jane Eyre!), and they assert on the strength of Woolf’s diary entries and the extant correspondence that the Mansfield/Woolf friendship “would profoundly influence the course of English literature” (xvii).

But for the exaggerated claims about the course of English literature, A Secret Sisterhood adds nothing to what previous biographers, and Woolf herself, said of her complex, sometimes frosty, sometimes warm friendship with Katherine Mansfield. Claire Tomalin pays sufficient tribute to Jane Austen’s friendship with Anne Sharp in her biography, Jane Austen: A Life. Lucasta Miller’s The Brontë Myth puts paid to the mythologizing of Charlotte Brontë against which Midorikawa and Sweeney take aim, and Pauline Nestor, in her monograph Female Friendships and Communities, explores the importance of Mary Taylor to Brontë as well as of Beecher Stowe’s correspondence with George Eliot. In order to justify their contention that specifically literary friendships between women have been ignored while male friendships have been celebrated, the authors have also ruled out mentioning other female friendships that enriched the lives of their subjects and that should dispel any lingering notions that such relations were few and insignificant. There was, for instance, the intimate and enduring friendship between George Eliot and Barbara Bodichon, the eminent women’s rights activist, artist, and educator who founded Girton College, and the close friendships between Virginia Woolf and her sister, the artist Vanessa Bell, and with her friend and sometime lover, the novelist, Vita Sackville-West. Midorikawa and Sweeney make the rather self-serving assertion that Woolf’s relations with Mansfield, “her literary equal,” have been overshadowed by her later friendship with Sackville-West, “the popular novelist,” because Woolf had yet to acknowledge the sexual attraction to women that would fascinate her later biographers (224). This assertion seems to me particularly disingenuous, first, because it ignores the fact that Woolf and Sackville-West were close friends and frequently acknowledged their importance to each other’s work, and second, because the literary quality of the secondary figure in each “secret sisterhood” is not an issue in the other pairings. Anne Sharp never published the plays she wrote for domestic performance and with the exception of a brief response to Mansfield Park (she preferred Pride and Prejudice) there is no recorded evidence of what the authors refer to as “a collaboration” (51). Mary Taylor only managed to publish one unremarkable novel decades after Charlotte Brontë had died, and her letters to Brontë contain scant exchanges on literary matters. For friendships to be “secret,” in other words, the authors are obliged to avoid the more evident and celebrated examples of women’s intimate connections; and to be “literary,” quality does not matter, unless, of course, it does.

The authors are repeatedly obliged to speculate where there is no evidence, to exaggerate influence when there is little to go on to corroborate it, and to present as “little known” what is widely available information.

What Midorikawa and Sweeney have done, which may make for the appeal of their book, if one sets aside the dubious claim that wrongs are being righted, is to dramatize incidents drawn from the letters and diaries of the women they write about. Scenes of reading or writing are themselves presented in narrative fashion; “missives” are “penned,” letters delayed and anxiously awaited. The letters exchanged by Charlotte Brontë and Mary Taylor, after the latter emigrated to New Zealand, are presented as episodes of high tension: “Across continents and a time lapse of several months Mary’s voice seeped from the blue-tinged paper” (108). George Eliot waits two years for a letter from Beecher Stowe: “In the chill of her north London home, Marian surveyed the day’s post laid out before her” (168). “The pages she grasped in her fifty-two-year-old hands were largely taken up by a long commentary on the work of several spiritualists known personally to her friend” (169). And here is Woolf reading Mansfield’s “Bliss” for the first time: “As Virginia began to read, her friend’s words gradually disturbed the peacefulness of the summer evening” (217).

I am not immune to the hunger to know more about cherished authors or to the desire to imagine an intimacy across time with their sufferings, their romances, their struggles to be read and admired. It is the same desire that, for many of us, sustains our passion for fiction. Jane Austen has become a character as fascinating as Elizabeth Bennett but with the added advantage, at least as far as the possibilities for expansion are concerned, of a life that can be documented in letters and memoirs and reimagined in innumerable forms. Homes can be visited, objects displayed, friends and relatives whose own lives gain luster through association can be inquired after; new perspectives will continue to be shed on long-established biographical fact. There are even a few secrets yet to be mined. What disappoints in this entry to the vast archive of material produced by author-love is the disparity between what is claimed and what is offered. For readers tantalized by these familiar names, and by the alluring promise of secrets, sisterhood, and friendship, A Secret Sisterhood may offer some pleasures. But for those enthusiasts who are eager to indulge their appetite for more information about these extraordinary women and their creative lives, this is thin gruel, indeed.