My last name has an accent mark. It is Tarragó, not Tarrago, not Tarragon like the herb often used in French cuisine, or Tarragona, the port city in Spain.

Growing up in the United States with a last name with an accent mark is a little weird. It is cumbersome to insert when typing and is rarely respected when written. And then there is the decision to even include the accent mark. I always have, thanks to a mother, who despite it not being her own family’s last name, emphasized the importance of keeping the letter “o’s” little Tintin-like tuft of hair.

Names are special. Whether you are John or Vladimir, Susan or Xochi, your name is your name. You did not choose it. You respond to it, you sign next to it, and in general, you would prefer if it were pronounced and written correctly.

I always have, thanks to a mother, who despite it not being her own family’s last name, emphasized the importance of keeping the letter “o’s” little Tintin-like tuft of hair. Names are special. Whether you are John or Vladimir, Susan or Xochi, your name is your name.

I have grown accustomed to seeing my last name written without its little tick. From state IDs to visitor passes and anything imaginable in between, Tarrago is the norm. I am just content that it is even spelled properly. However, I do feel genuinely happy when someone takes the time to include the accent mark in my name. Something lights up inside.

You see, my name just looks a little naked without its accent mark. And with good reason. Accent marks are not just useless flair. Not only is the accent mark in my last name part of my family’s history, it also serves an important purpose. It tells you on which syllable to put emphasis. In my case, Tarragó is TarraGO, think “sweet and LOW” or “kiss and GO.”

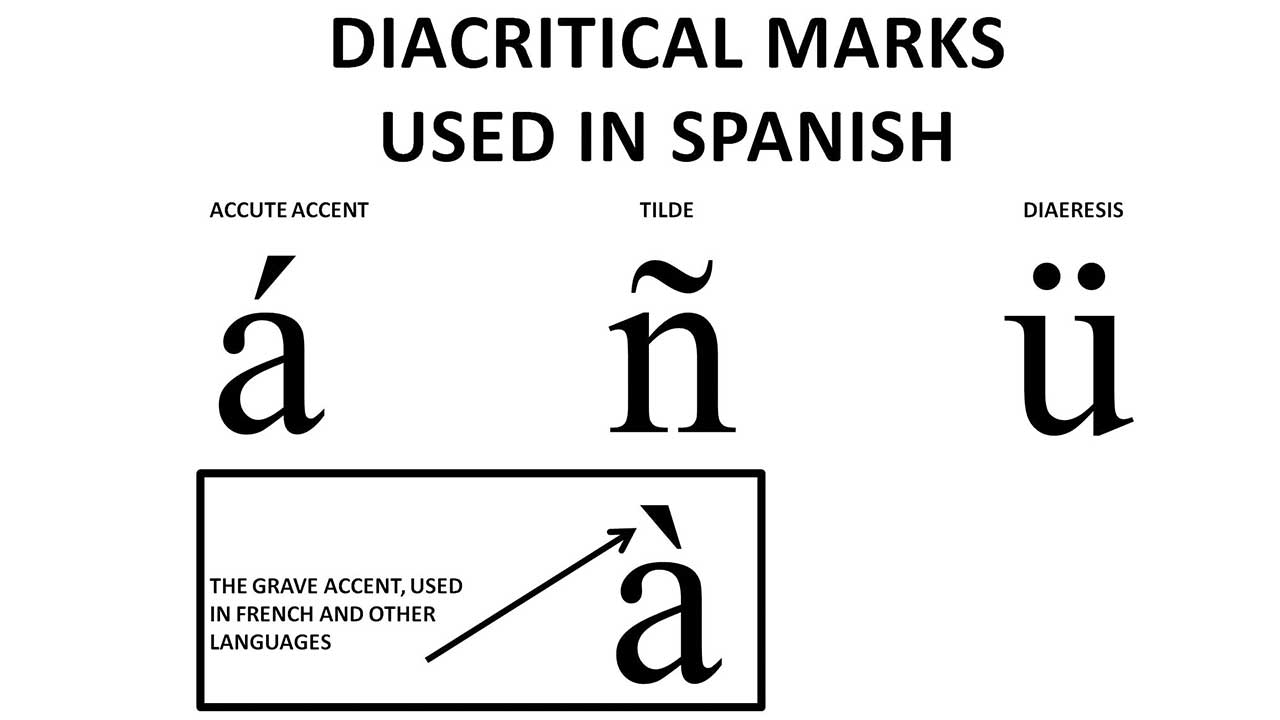

Accent marks are part of the larger linguistic category of diacritics. A diacritic is essentially a sign that can go above or below a letter and changes the sound of letters and words. So when you are eating a jalapeño and working on your resumé, you can thank diacritical marks for your stellar pronunciation of the two. But the inclusion or exclusion of these signs can even change the meaning of a word or a name. Bartolo Colón, the oldest player in the MLB and proud bearer of the nickname ‘Big Sexy,’ would have a completely different name if the accent mark in his last name were removed. ‘Colón’ would become ‘colon,’ like part of your large intestine. The equally common last name Peña, sported by Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto or American actor Michael Peña, becomes pena (pity) if its diacritic is omitted.

And it is a pity to have your name consistently misspelled and mispronounced. The New York Times chronicles an anecdote from Dominican baseball player Eduardo Nύñez. As the big-time San Francisco Giants shortstop sat in the locker room ahead of the Major League Baseball All-Star Game last year, a clubhouse employee walked in, holding his jersey, but called out an unfamiliar name. “Noonez,” the employee said. Without the diacritic “ñ,” the employee did not know how to properly pronounce Eduardo’s last name. And this is the name of a top-tier professional baseball player, an all-star with a $4.2 million salary, whose name is on the lips of commentators and on the backs of countless jerseys across the country. It is shameful that a player can give everything to his team and his fans, and they do not even pronounce his name correctly.

Bartolo Colón, the oldest player in the MLB and proud bearer of the nickname ‘Big Sexy,’ would have a completely different name if the accent mark in his last name were removed. ‘Colón’ would become ‘colon,’ like part of your large intestine. The equally common last name Peña, sported by Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto or American actor Michael Peña, becomes pena (pity) if its diacritic is omitted.

Out of this reality, the Ponle Acento (“Put an Accent on It”) campaign was born. Sponsored by Major League Baseball in partnership with cultural branding agency LatinWorks, the campaign sought to put accent marks on the names on players’ jerseys. Traditionally accent marks have been omitted. By having names correctly spelled on their jerseys, the movement is a valuable way in which to recognize the important contributions that Latinos—who make up over a quarter of the MLB—have made to the sport.

“We always knew there was a big parallel between the U.S. and baseball. Minorities are a fundamental part of both,” LatinWorks associate creative director Alberto Calva told Adweek. “Twenty percent of the U.S. population is comprised of Hispanics, roughly equal to the 27 percent of Hispanics in MLB’s rosters. This country and this game look like they do today because of what Hispanics have brought to the table.”

The movement became a hashtag and spread among top players in the MLB. Since its inception last year, 30 players and coaches have added accent marks to their jerseys. Among them, Seattle Mariners second baseman and 2017 MLB All-Star Game MVP Robinson Canó has made the change. And of course, Eduardo Nύñez has, too.

But the politics surrounding accent marks extends past the limelight of celebrity athletes. In many states, children born with names that include accents marks are not allowed to have these diacritical marks on any official documents. Strikingly, all four states that border Mexico, California and Texas included, do not allow accent marks.

A look at the most popular male baby names in the country from this past year shows a considerable number of names that would normally include accent marks if written in Spanish: Sebastián, Julián, Adrián, or Ángel. All are well within the top 100. For girls, Sofia, written Sofía in Spanish, is the 14th-most popular female baby name in the entire country.

The issue is even more pronounced in California and Texas. Take the name ‘José’ as an example. Of course there will be variations, but by and large, the name is traditionally written with the accent mark. According to the Social Security Administration, during 2016 alone, 1,117 babies were named Jose in California. The same year, Jose was the ninth most popular male name in Texas with 1,421 newborns receiving the name. Jose was the 77th most popular male name in the entire United States in 2016, two spots behind Adam, and right in front of Ian. For all of these newly born Josés, none will have an accent mark on any official documents.

A look through state laws governing naming restrictions reveals the variety that occurs by state. So while you can name your child R2D2 in Hawaii, Illinois, or South Carolina, you can not name your child Sofía or Tomás in the majority of states.

Efforts are being made for this to change. In California, a bill was introduced this past spring that would overturn the state’s ban on diacritical marks in official documents. The change would allow for diacritical marks on marriage licenses, and certificates of birth and death. The Josés, Zoёs, and Chloёs would be able to live and die under their correct name. The bill, introduced by California Assemblyman Jose Medina, was passed unanimously in its first round of voting by a California assembly committee.

“Right now, we are all talking about California being a place where your values can be respected, whether you are an immigrant or of a different ethnicity, or whether you come from another country, and it all starts with the name,” Medina said.

It seems that Texas is following suit. State Representative Terry Canales filed a bill this past February aimed at allowing diacritical marks on official documents. As he explains, the state was Spanish-speaking before it was English-speaking. Texas, like the United States, has no official language.

“It’s absolutely critical that we use the accents or diacritical marks because that’s your name,” Canales has said. “You are your name. That’s your identity.”

Besides the obvious importance of having your name properly spelled on official documents, proponents of these bills contend that the law is not applied equally. Names such as O’Doyle or O’Donnell are allowed, while names with diacritical marks, particularly those of Hispanic origin, are not.

A look through state laws governing naming restrictions reveals the variety that occurs by state. So while you can name your child R2D2 in Hawaii, Illinois, or South Carolina, you can not name your child Sofía or Tomás in the majority of states. It is time for that to change.

No, I do not go crazy and correct people in email correspondence nor write back to membership subscriptions asking for my name to be changed, but I do take the extra infinitesimal amount of time to add my accent mark, particularly when writing by hand. My signature includes it, my school work includes it, and I’ll be damned if this article does not include it as well.

Having been born in the state of Nevada, which does not allow for diacritical marks, my name legally is not Delmar Tarragó. Instead, my birth certificate has the blander and incorrect Delmar Tarrago. My death certificate will likely have the same. But this does not prevent me from including my accent mark whenever I am able to do so. No, I do not go crazy and correct people in email correspondence nor write back to membership subscriptions asking for my name to be changed, but I do take the extra infinitesimal amount of time to add my accent mark, particularly when writing by hand. My signature includes it, my school work includes it, and I’ll be damned if this article does not include it as well. At the end of the day, it is my name.

And with all of this in mind, for those with accent marks in their names, I urge you to do the same. In the face of rhetoric that diminishes and marginalizes our immigrant communities, we must remind ourselves and those around us that our culture and our heritage should not be erased. Diacritical marks might seem like a tiny blip in the larger picture of tumultuous politics and proposed policies that actively harm our minority populations, yet they serve as a reminder of our important presence and contribution to this nation.

Our names are our names. If we can correctly pronounce and write O’Donnell or Coach Krzyzewski, there is no reason that for Lucía or Pérez we cannot do the same. Reclaim and remain proud. Because let us face it … we are here to stay.