A Jesuit’s Reluctant, Beautiful Confession

October 22, 2024

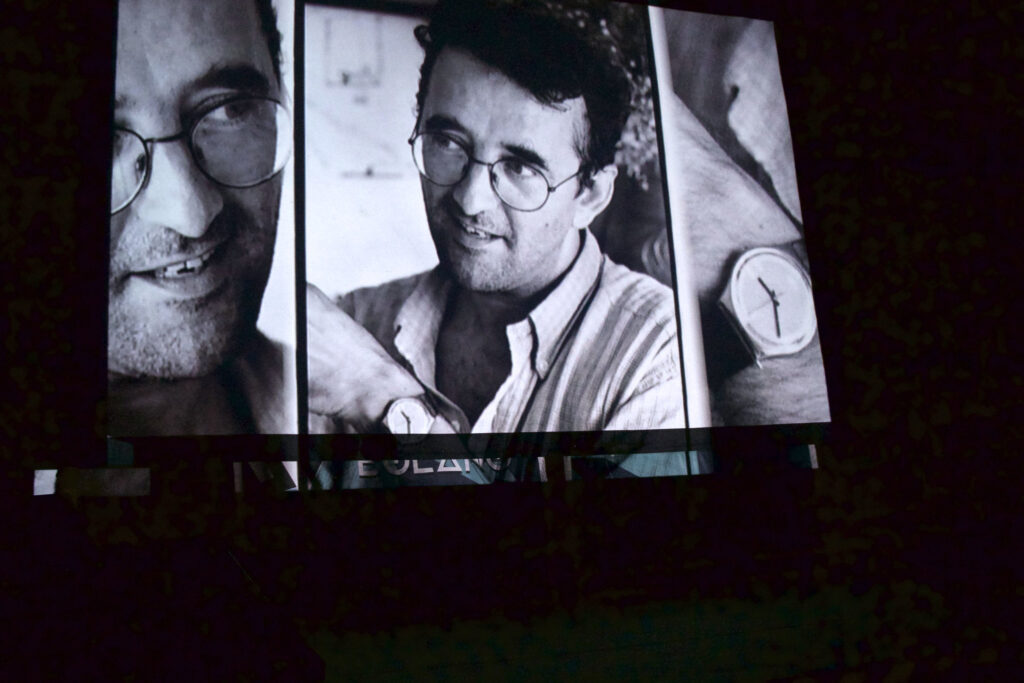

“A respected novelist while alive, in death Bolaño has soared to cult status.” Whoever wrote that for Newsweek was not exaggerating. Though Roberto Bolaño’s name does not glide off most Midwestern tongues, those who know his work are fervent in their praise. Now Picador intends to expand that cult by reissuing Bolaño’s books, starting this fall with By Night in Chile, Antwerp, and The Return.

Offered review copies, I chose By Night in Chile. A wisp of a book, nothing like his 672-page triumph, The Savage Detectives. Surely I could manage it. Surely I should manage it. Writing after Bolaño’s death, literary critic James Wood said By Night in Chile was “still his greatest work.” Susan Sontag called it “the real thing, and the rarest: a contemporary novel destined to have a permanent place in world literature.”

Plus, the novella is a long, reluctant confession by a Jesuit. Having been put through my paces by his brethren for nine challenging years, I was intrigued.

By Night’s first delight is its epigraph: “Take off your wig.” Chesterton. No more deceit, it promises, no more pretending. Yet turn one page, and Father Sebastián Urrutia Lacroix is beginning his spin, rationalizing his sins of omission and complicity even on his deathbed. He defends, he protests; does he even want to confess? He cannot pry off the boards he hammered hard to seal away his sins.

A priest who wears his cassock as a talisman, Lacroix keeps donning it in situations where he did not intend to wear it. He hides behind its credential when he, himself an aspiring poet and critic, meets the famous Pablo Neruda; meets a renowned literary critic; is forced to meet one of the peasant farmers he despises. When Lacroix mingled “with the best-dressed men” in Europe, he recalls, “there I was, with my cassock fluttering in the air-conditioned breeze or the gusts that issue from automatic doors when they open suddenly, for no logical reason, as if they had a presentiment of God’s presence, and, seeing my humble cassock flapping, people would say, There goes Fr. Sebastian, there goes Fr. Urrutia, that splendid Chilean, and then I returned to Chile, for I always return, how else would I merit the appellation splendid Chilean.”

Later, he will see his costume more clearly: “My cassock flapping in the wind, my cassock like a shadow, my black flag, my prim and proper music, clean, dark cloth, a well in which the sins of Chile sank without a trace.”

I call it a “costume,” which is harsh, because he is perfunctory in his religion, though he loves its power. Invited into the home of a farmworker, he is annoyed to learn that a child has either fallen ill or died—and does not bother to find out which. “Even prayer is boring in the long run,” he remarks. He would far rather be part of the literary cliques, even if it means enduring “the idle but agitated and often indiscreet chatter of the Parisian salons.”

Not a priestly priest, you see. A man whose arrogance takes turns with querulous insecurity. His confessions are sly. “Silences rise to heaven too, and God hears them, and only God understands and judges them, so one must be very careful with one’s silences,” he observes. “I am responsible in every way. My silences are immaculate.”

His silences have shown complicity with the violent regime of General Augusto Pinochet, to whom he gave lessons in Marxism so Pinochet could understand his enemy.

Bolaño was living in exile when he wrote By Night, and his angry love for his homeland comes through—but with surprising lightness. One of his characters suggests “a good Chilean supper” so the guest “could see for himself how well we live in Chile, in case he thought that over here we were still walking around wearing feathers.” Lacroix later references “that sense we Chileans posses to an uncommon degree, the sharpest of all our senses, the sense of the ridiculous.”

The experience of reading these 130 unparagraphed pages, thanks to the consummate skill of the author, is that of being held in someone’s arms and swirled through a pool of water. The words flow and you do not want them to stop, do not need a paragraph break or even a breath because you are inside this old priest’s head thinking with him, and one image morphs smoothly into the next, one sentence leads inexorably to the next because he is terrified of stopping, terrified of thinking honestly about his life and realizing what he has done and, worse, what he has failed to do.

Bolaño’s command of language is stunning, even in translation. He slips beauty and terror into his sentences when you least expect them. Description comes in layers: “We move like gazelles or the way gazelles move in a tiger’s dream…. We move as if we had no shadows and were unperturbed by that appalling fact.” He reports conversations like a discerning gossip, noting the smallest quirks, like “that diplomatic hmm hmm noise that can mean absolutely anything.” He plays with words and thus with us, describing a Guatemalan painter as “skinny, wasted, rickety, pinched, scrawny, gaunt, haggard, debilitated, emaciated, feeble, drawn, in a word: extremely thin.”

Lacroix is modeled on the priest and right-wing literary critic José Miguel Ibañez Langlois. Another of Bolaño’s characters, a woman who invites writers and artists to her elegant salons, is modeled after Mariana Callejas. She and her American husband worked for the secret police, entertained on their main floor, and tortured those they interrogated in the basement. Lacroix tells us he only went to a few of the salons; he explains that another guest discovered a murdered man in one of the bedrooms. How did the couple expect to continue in this fashion? “With time, vigilance tends to relax,” Bolaño reminds us, “because all horrors are dulled by routine.”

His writing, by contrast, is never dull. The text has a strange, propulsive rhythm, with a brush of snare drums to introduce each symbol or allegory. Lacroix is invited to Europe by Mr. Raef (Fear) and Mr. Etah (Hate). They have an import-export business, these two, a clam-tinning plant. They want him, as a loyal member of Opus Dei, to travel from one European church to the next, reporting on their preservation. Which takes the form of falcons, trained by the priests to kill pigeons—bloodying even the white pigeons we know as doves of peace—so their excrement will no longer harden on the gothic spires.

Later Lacroix publishes a good review of a book called The White Dove, “although deep down I knew it wasn’t much of a book.”

The motif that holds By Night in Chile together is his accuser, “the wizened youth” who has made allegations Lacroix is still trying to deny. Wizened? An aging, dessicated youth? Is it his own early idealism, so fast faded we never saw it? Now he feels “the whipcrack of the years, the precipice of illusions.” Clues about the youth arrive sporadically—he is “just a kid from the south, the rainy borderlands”—but none clinch his identity.

The wizened youth accuses Lacroix of being “an Opus Dei queer.” Lacroix snaps that he has never denied belonging and was their most liberal member. We see him tormented by homosexuals in his dreams and approached in daylight by men to whom he does not succumb. His own repression parallels his country’s.

When rebellion exploded in the streets of Santiago, he and the literary critic he admires “stayed put and kept still, only our hands moving, lifting the coffee cups to our lips, while our eyes looked on, as if what they were seeing had nothing to do with us, as if we hadn’t noticed what was going on, in that typically Chilean way.”

By the novella’s end, Lacroix has informed his accuser, “You better get used to it.”

“The wizened youth, or what is left of him, moves his lips, mouthing an inaudible no. The power of my thought has stopped him,” the Jesuit brags. “Or maybe it was history. An individual is no match for history.”

Not even one who is able to capture it this powerfully.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.