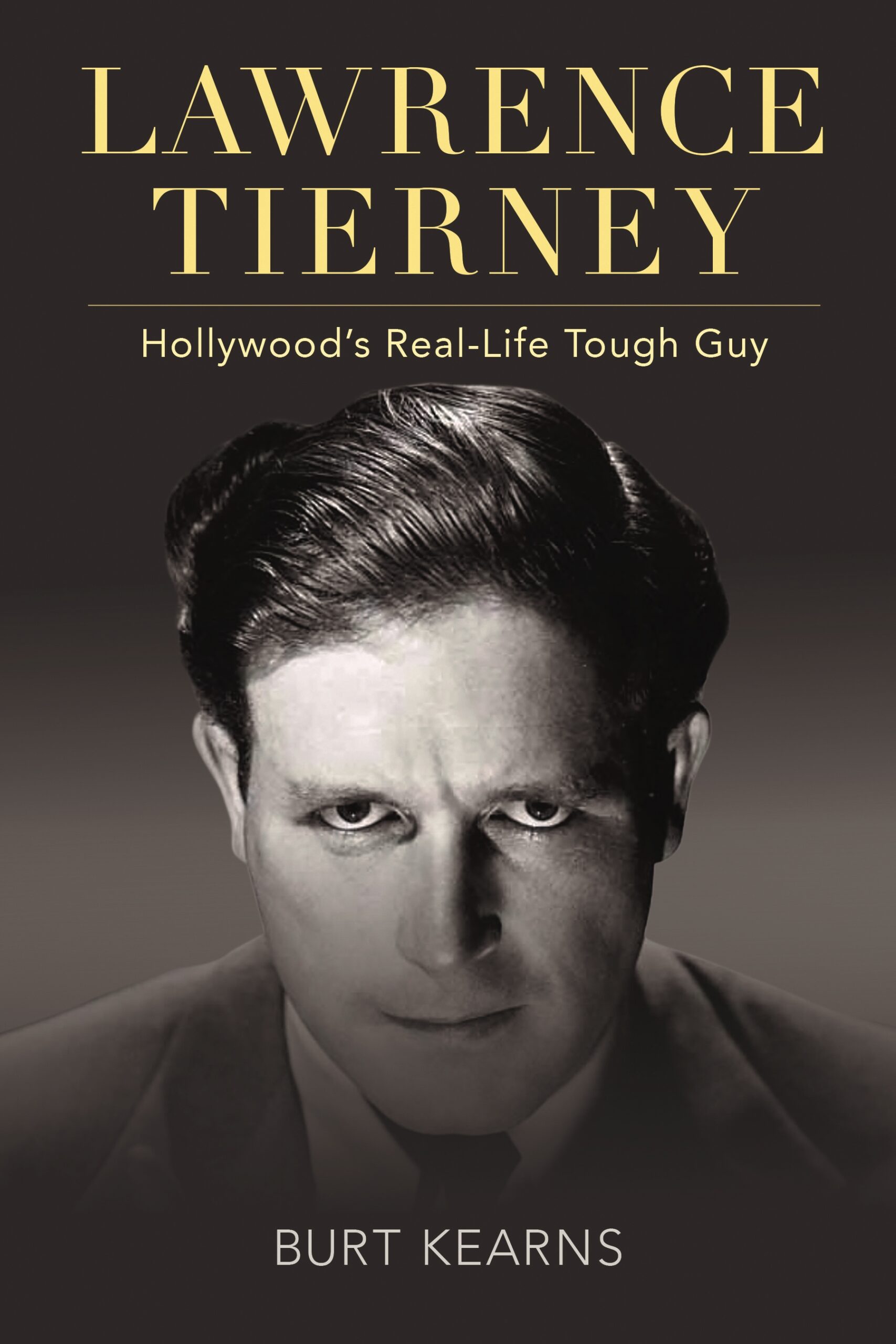

Who’s Afraid of Lawrence Tierney?

The story of an actor who became how he was typecast

By Gerald Early

October 30, 2024

Lawrence Tierney: Hollywood’s Real-Life Tough Guy

Reservoir Dogs and the Return of Lawrence Tierney

“Quentin Tarantino assumed that Lawrence Tierney was dead,” writes Burt Kearns in Lawrence Tierney on the famous director’s 1991 shoot of Reservoir Dogs. (296) As things turned out, Tarantino probably wished his assumption had been right that Tierney was dead. It would have saved him the agony of working with an aged, bald, overweight, uncooperative lout of an alcoholic actor. Tarantino thought Tierney had been shot to death in a whorehouse in Mexico, which would not have been a strange ending for a man who lived such a turbulent and peculiar life. “‘He was the toughest guy of ’em all,’” Tarantino gushed to a friend. (296) Let us say Tierney had the reputation of the toughest of ’em all. But it might have been a more accurate observation on Tarantino’s part to have said that Tierney was a survivor of his special brand of self-destruction. In any case, to Tarantino’s great surprise, in the early 1990s, Tierney was living behind the Hollywood library, safe from Mexican sex workers and bullets, although not entirely immune to his self-destructive habits.

Tarantino signed Tierney to play Joe Cabot, the criminal mastermind who assembles the heist team central to Reservoir Dogs. Filming started on July 29, 1991. Tierney hated Tarantino’s dialogue and his direction, so he refused to learn his lines, thinking them too convoluted and repetitive, and fought being directed, even being touched. He was, in a word, difficult. By August 2, Tarantino and Tierney, who, by then, was hated by nearly everyone on the set, got into a fistfight after Tarantino yelled at Tierney, “You’re fucking fired! Take your fat fucking ass off my fucking set.” (300) Actor Tim Roth parted the two combatants before anyone was seriously hurt. Tarantino had to almost instantly rehire Tierney, running after him as Tierney was departing, as he could not afford to replace him or to reshoot what he had already filmed with the actor. Reservoir Dogs was a low-budget film, after all. In the end, the ordeal turned out beneficial for both men: Tarantino gained street cred for working with the cantankerous B-movie star of the 1940s and early 1950s, and Tierney was introduced to a new audience as the toughest of ’em all. The film rekindled the legend of the man known for playing John Dillinger.

Dillinger and the birth of Lawrence Tierney

When RKO lent an upstart Irish-American actor named Lawrence Tierney to Monogram Studios to star in Dillinger, he was, according to gossip columnists like Louella Parsons, “six feet tall, 25 years old and considerably better looking than the late Dillinger.” (15) More precisely, Tierney was, according to Kearns, “175 pounds, a shade over six feet tall, with an athletic build, gray-green eyes, brown hair, and a distinctive flesh-colored mole on his chin.” (7) In short, he had the make-up, the looks, of a matinee idol, which he never became. More importantly, Tierney had a presence, chilling and forceful, which is why he was chosen to play Dillinger, the notorious bank robber and jail breaker, Public Enemy Number One, who went down in a hail of FBI bullets outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago on July 22, 1934, at the age of thirty-one. Tragedy and farce in one fell swoop. There was something about Tierney, almost poetical, that made him a natural to perform the absurdity of a stupid and defiant gangster’s life. Filming Dillinger began on October 10, 1944, and was completed in twenty-one days, a typical shoot schedule for a Poverty Row studio, which is what Monogram, which usually did westerns, was, in the parlance of the movie business. Tierney caused no problems during the shoot, but years later costar Anne Jeffreys said he threatened to throw her down a flight of stairs at the top of the set. A gaffer prevented it. He “was all right sober,” she said, “but if he had one drink—wow. He was a wild man.” That would become the story of his life. (15-16)

Let us say Tierney had the reputation of the toughest of ’em all. But it might have been a more accurate observation on Tarantino’s part to have said that Tierney was a survivor of his special brand of self-destruction.

Dillinger did not get good reviews. But as a gangster movie about a real-life, famous, outlandish, dramatically shot-down, Depression-era bank robber, it was, in some respects, review-proof for its time. The film was a hit, and so was Tierney’s cold-blooded performance. He transcended the historical Dillinger and became the embodiment of a pure psychopath, something almost approaching a perverse, obscene expression of artistic will, the ultimate violent rebel without a cause. As a viewer, you cannot take your eyes off him. And when he is not in a scene, you crave his presence. He is riveting. Tierney is the movie; the rest of the actors are there to fill out the plot. His career should have been made with this film. He should have become a big star. All the gossip columnists thought so. Many people in the industry thought so. But he faltered and ultimately failed. Because he faltered, he fell victim to what so many charismatic actors—from Errol Flynn to Sean Connery—feared: typecasting. He was always the tough guy, the unhinged sociopath as in Born to Kill (1947), his best film and his most blood-curdling performance as a man who is not, as costar Claire Trevor’s character puts it in the film, “a turnip” as she feels most other men are. He is, in fact, a perverse, immoral ideal, an Ayn Randian hero on steroids. Tierney would have made a terrific Mike Hammer. Or, if he had been British, he would have been a better James Bond than any actor who wound up playing the character. Born to Kill might be obviously said to be about toxic masculinity, as it were, but it is more brilliant than that, as it is also about toxic femininity and how each fuels the other.

What destroyed Tierney was drinking and brawling offset. Lawrence Tierney is a solid biography that describes in detail Tierney’s career as an actor, which are the best parts. The worst parts, where the book becomes a slog, are the endless episodes detailing Tierney’s drunken street and bar brawls (he seriously assaulted several people over the course of his journey in hell), his uncontrolled drinking, his inability to stay on the wagon despite his promises, his countless arrests, at least forty by my count in the book, and his unbelievably good luck in never being sent to prison despite constantly breaking the law and often not appearing in court. (I doubt if the court system would have been so extraordinarily lenient had he been a Black man, but I digress, I assure the reader, without bitterness.) Studios refused to use him because he was unreliable, although, to his credit, he was never drunk on the set and would usually do his job professionally. But the studios always wished in some way that they could use him in some way, rehabilitate him. Film work became intermittent occasions between drunken binges: Step by Step (1947), Bodyguard (1948), The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), The Hoodlum (1951), Female Jungle (1956), varying quality B-films with varying performances that often seem like variations of Dillinger or efforts to make movie-goers wish that he could reprise Dillinger. The recitation of self-destruction becomes mind-numbing after a bit and, for this reader, sandbags the book, for the biographical narrative, after a point, ceases to have a point, except to say, in words of Peter Fonda in Easy Rider, Tierney “blew it.” But perhaps the repetition has a kind of readerly virtue in just getting through it. Tierney survived, and in the end, you, as the reader, have survived too.

He transcended the historical Dillinger and became the embodiment of a pure psychopath, something almost approaching a perverse, obscene expression of artistic will, the ultimate violent rebel without a cause.

Two of Tierney’s brothers became successful actors, Scott Brady in particular, who appeared in both features and on television. I like four Brady films: I Was a Shoplifter (1950)—featuring a very young Tony Curtis—, Canon City (1948), about a prison break, White Fire (1953), a British crime film where Brady tries to save his brother from the gallows for a crime he did not commit, and that strange classic western, Johnny Guitar (1954). In many respects, Brady had a far more successful career than his brother, but Lawrence Tierney is still the legend. It is like the story of the Prodigal Son. The faithful son is, well, the faithful son but the bad boy gets all the attention and affection. Tierney was not uncouth when sober: he could recite reams of poetry by W.B. Yeats and John Donne and was, in fact, well-read. He had the stereotypical wildness of a male Irish creative. His body could not contain what he wanted to express, and his mind could not vent his body’s needs properly. This made him thrilling, undisciplined, artistic, and stupid in one complex mix.

For me, the real tough guy of Hollywood was an actor and scriptwriter named Leo Gordon, whose tough, mean characters got punched out in so many fights and brawls in television and movie westerns by actors ranging from James Drury to Steve McQueen that it is almost comical. The tough, imposing, craggy-faced actor never won a staged fight, and those fights were almost always very physical with little use of stuntmen. Gordon served five years in San Quentin for armed robbery and was shot in the stomach by the police to boot. He knew something about fighting in real life. Even watching him as an old adult intimidates me. An engaging biography awaits.