Campaign That Tune

How campaign theme songs speak to opposing camps.

By Kelsey Klotz

October 6, 2016

In an election year that feels more divisive than any other, in which votes seem just as likely to be cast against one candidate as for the other, it may seem strange to focus on how presidential candidates can create a community of supporters.[1] But these supporters are crucial to any candidate’s ground game: without volunteers, local spokespeople, or even positive social media, bumper stickers, and yard signs, candidates risk the impression that they lack the votes needed to win. This can create a downward spiral—after all, as third party candidates well know, it is difficult to convince someone to vote for a presidential candidate who looks as if he or she cannot win.

Obviously, a presidential candidate’s political beliefs and party affiliation will create a community of supporters (and, ideally, voters). But political campaigns also often use music as an important tool to enhance a feeling of community, particularly when candidates select music that is already well-known to their supporters. As musicologist Dana Gorzelany-Mostak argues, “pre-existing songs [songs initially composed for other purposes] project a cluster of associations onto a politician, thus contributing to their brand, or, their presidentiality.”[2]

Popular songs can serve as a powerful binding tool in the formation of a community, in large part because of their emotional content. However, musicologist Simon Frith, who specializes in popular music, writes that popular songs do more than simply reflect emotions; using the example of love songs, Frith explains that these songs “give people the romantic terms in which to articulate and so experience their emotions.”[3] When a group of people listen to the same set of songs, or have a similar repertoire, they possess similar terms to explain their emotions. For instance, one of the primary campaign songs played by Bill Clinton’s campaign in 1992, “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow,” might have prompted his supporters to think of Clinton as a forward-thinking presidential candidate who would continue to plan for the future. The song likely helped to create a common language for supporters, as they attempted to explain why Clinton was their chosen candidate. Using a common language, whether verbal or musical, can ultimately create a community of people (in this case political supporters) that votes, sings, speaks, and even feels similarly. Because of this, a candidate’s repertoire of songs can serve as a useful tool to allow supporters to feel heard while simultaneously telling voters how (or perhaps simply that) the candidate will address voters’ concerns.

When a group of people listen to the same set of songs, or have a similar repertoire, they possess similar terms to explain their emotions.

In the rest of this essay, I’ll explore the two current major party candidates’ song selections at their campaign rallies. What kind of communities are these candidates and their campaigns attempting to create with their musical choices? Further, what can their music choices tell voters about their message?

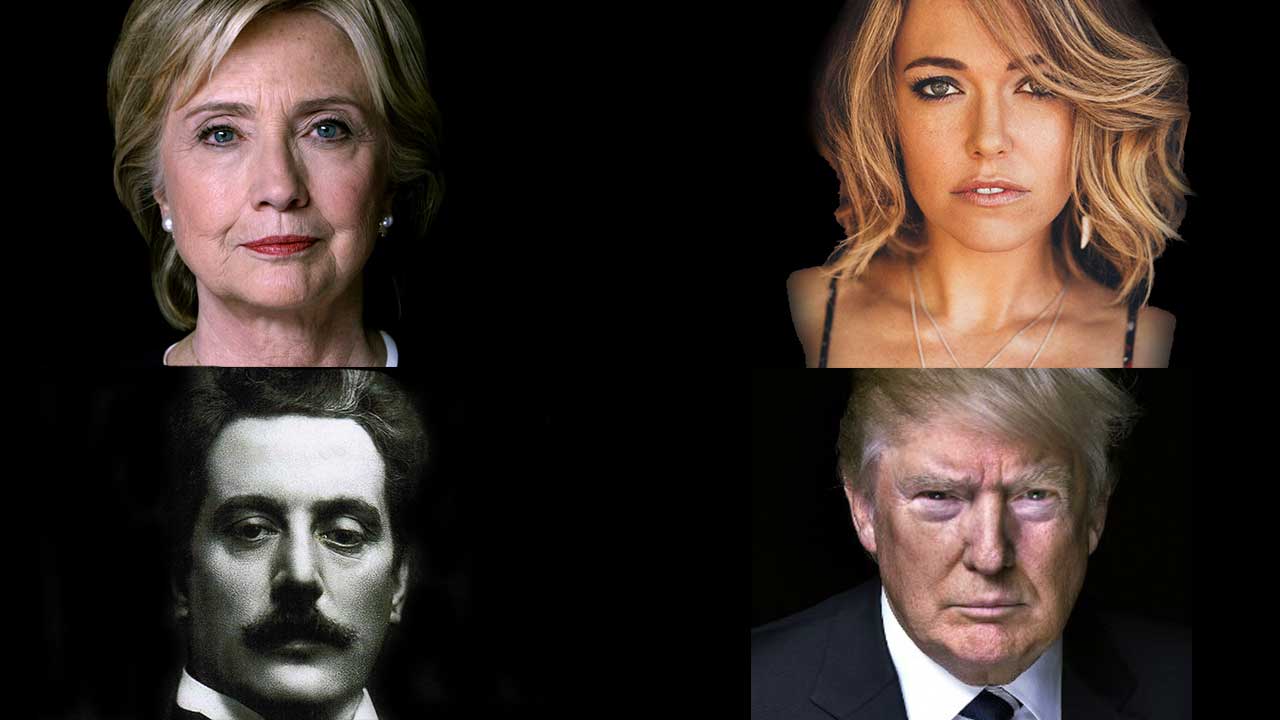

The 2016 election and its music

Both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s respective campaigns have used music to comment on trending topics during the campaign; for instance, the Trump campaign played Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” while Ted Cruz’s Canadian birth was a major discussion point, and James Brown’s “I Feel Good” welcomed Clinton onto the stage when Clinton returned to the campaign trail following a controversial bout of pneumonia. These songs may also reflect both Trump and Clinton’s targeted audience: for Trump, the selection of a Springsteen song may reveal an attempt to cater toward a mostly white, working-class audience; for Clinton, “I Feel Good” may be an attempt to show how “with it” she is with minority, and particularly black, voters. Furthermore, both songs are jokes that Clinton and Trump’s supporters get to be in on, further enhancing a sense of collectivity for each. These types of songs reinforce a sense of common knowledge through their shared references.

But just as Clinton and Trump demonstrate disparate approaches to campaigning, policy, press junkets, supporter interaction, advertising, etc., their varying musical strategies reflect two entirely different campaign styles. Whereas the Clinton campaign’s musical choices individually reflect a common goal, the Trump campaign’s musical choices must be taken as a whole to understand Trump’s ideal community.

Trump: Make America Great Again

Commentators have often found the Trump campaign’s musical selections to be as disconcerting as they did his initial viability as a political candidate. With musical selections ranging from Elton John to Bruce Springsteen to the Beatles to Adele to Andrew Lloyd Weber’s Broadway hits to Puccini, even some of Trump’s supporters have found his music difficult to rally behind. As Chris Richards of The Washington Post writes, “Nobody’s singing along to any of these tunes. Nobody’s bobbing their head … Instead of energizing this crowd, Trump’s playlist simply replaces silence with a different kind of emptiness.” Rebecca Sinderbrand, also of The Washington Post, noted that some members of a crowd in Nevada actually booed the beginning of the Puccini aria “Nessun Dorma.” There seems at first glance to be little common narrative behind the collection of songs aside from possibly being songs that Trump himself seems to enjoy. However, a closer look reveals how deeply engrained Trump’s infamous campaign slogan is with Trump’s song choices, and in fact, may offer an alternative understanding of the slogan.

Commentators have often found the Trump campaign’s musical selections to be as disconcerting as they did his initial viability as a political candidate.

Trump’s slogan, “Make American Great Again,” has come under attack from the left (and the right): for many, including Bill Clinton, the slogan implies that Trump yearns for the seeming prosperity of the 1950s—even if that prosperity was only shared among white, heterosexual, middle- and upper-class American males.[4] However, Trump’s musical preferences may point to a different decade as his vision of a prosperous America. Below is a table of musical selections I have learned of in various articles; it is by no means exhaustive, but it does represent many of the songs Trump uses regularly, as cited by a number of journalists who have attended Trump rallies.

| “Here Comes the Sun,” Beatles | 1969 |

| “You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” Rolling Stones | 1969 |

| “Rocket Man,” Elton John | 1972 |

| “Hey Jude,” Beatles | 1973 |

| “We Are the Champions,” Queen | 1977 |

| “Memory,” from Cats, by Andrew Lloyd Webber | 1981 |

| “Don’t Stop Believing,” Journey | 1981 |

| “Start Me Up,” Rolling Stones | 1981 |

| “Eye of the Tiger,” Survivor | 1982 |

| “Born in the U.S.A.,” Bruce Springsteen | 1984 |

| “Music of the Night,” from Phantom of the Opera, by Andrew Lloyd Webber | 1986 |

| “It’s the End of the World,” REM | 1988 |

| “Rockin’ in the Free World,” Neil Young | 1989 |

| “Nessun Dorma,” from Puccini’s Turandot | Opera: 1926;

Pavarotti Recording: 1990 |

| Air Force One theme |

1997 |

| “Rolling in the Deep,” Adele | 2011 |

| “Skyfall,” Adele |

2012 |

There are many observations that can be drawn from this list: 1) Nearly all songs were performed by white men (with the notable exception of the two Adele songs); 2) 13 of the 17 songs listed were released when a Republican was in office; 3) Of the 13 released when a Republican was in office, 7 were released when Ronald Reagan was in office; 4) Though the songs’ collective release dates span from 1969-2012, nearly half of the songs were released in the 1980s. Of course, Trump’s campaign may have selected songs from the 1980s to appeal to his voter base (which most polls show predominantly consists of white males older than age 30).

When considered with Trump’s biographical details, it seems that the decade for which Trump yearns most is not the 1950s, but the 1980s, when Trump, then in his late 30s and early 40s, came into his own as a real-estate investor. After being given control of his father’s company in 1971, Trump made his first major deal in Manhattan in 1978 (building the Grand Hyatt Hotel near Grand Central Station). Many deals followed: in 1981 Trump purchased the building that would become Trump Plaza; in 1983, Trump completed Trump Tower; Harrah’s at Trump Plaza in Atlantic City, a hotel and casino, opened in 1984, and Trump Castle opened in Atlantic City in 1985; Trump purchased Mar-a-Lago in 1985; in 1988, he purchased the Plaza Hotel and the Taj Mahal Casino in Atlantic City. Following Trump’s real-estate boom of the 1980s, he filed bankruptcy for various hotels and casinos four times between 1991 and 2009.

A common historical narrative of American triumph in the 1980s matches that of Trump’s personal successes in the 1980s. At the beginning of the decade, America was in the greatest recession since the 1930s; by 1984, Ronald Reagan was campaigning on the strength of the economic recovery that occurred during his presidency. America’s image abroad was likewise strong at the end of the decade; as historian Michael Schaller writes, “The United States stood ‘tall’ abroad, by 1989 the only true military superpower left in the world.”[5] Historian Michael Heale explains contemporary conservative understandings of the Reagan years like this: “Reagan rehabilitated conservatism, turned the nation to the right, practiced a pragmatic conservatism that balanced ideology and the constraints of politics, revived faith in the presidency and in American self respect, and contributed to victory in the Cold War.”[6]

Historian Gil Troy explains that such commentaries contribute to a three-part “Reagan storyline”: the first part features four failed presidents (Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter), a humiliated military, and run-away inflation; the second part sees Reagan elected president “with a mandate for change”; and in the final act, “the stock market soared, patriotism surged, the Soviet Union crumbled, and America thrived.”[7] Despite attempts by Bill Clinton in his 1992 presidential campaign to point out the growing social injustices of the 1980s (evidenced in Reagan’s opposition to affirmative action, the AIDS epidemic, the doubling of the prison inmate population, falling earnings for production workers, and the growth of homelessness), as well as the growth of the national debt, the “Reagan as Republican hero” storyline persists.

When considering Trump’s history and his apparent musical preferences in the context of this persistent narrative, it seems likely that the American dominance Trump yearns for is the same decade that most Republicans are nostalgic for.[8] The fact that Reagan’s campaign slogan in 1980 was also “Make America Great Again” further underscores Trump’s look back to the 1980s. And emphasizes, in the way two of his most noted supporters—Ann Coulter and the late Phyllis Schlafly—point out in their most recent books that Trump is the most plausible, if peculiar, reinvention of Reagan since Reagan left office. Ultimately, if we analyze the Trump campaign’s musical selections individually, they do not give a clear-cut sense of the identity of his supporters. (Do they go to the opera? Broadway? Do they prefer hair metal bands, or calm Beatles melodies?) The very irregular, even whimsical, nature of the list may signal to Trump’s supporters his honesty, his lack of pretension, his insistence on being himself which are the qualities that many of his supporters find most attractive about him. The fact that so many musicians have complained about Trump using their music validates many of his supporters’ view that he is an anti-establishment maverick, a rebel. When considered as a whole, his selections seem to point to a period and to a national character that many staunch conservatives praise—even those conservatives who refuse to support Trump.

Clinton: I’m With Her

Like Trump’s campaign, Clinton’s campaign uses music to create a sense of community among supporters; however, while Trump’s playlist as a whole supports his slogan, each song on the Clinton playlist supports Clinton’s pro-feminist, pro-millennial message of empowerment through togetherness. In mid-June 2015, the campaign (under Clinton’s name) released a Spotify playlist of campaign music full of music from the 2000s: it featured songs by the American Authors, Katy Perry, Kelly Clarkson, Pharrell Williams, John Legend, Jon Bon Jovi, Marc Anthony, Sara Bareilles, Demi Lovato, and Rachel Platten, among others. The oldest songs on the list were Mary J. Blige’s “Real Love” (1992), the Gap Band’s “Outstanding” (1982), and Jennifer Lopez’s “Let’s Get Loud” (1999).

Clearly, when compared to the Trump campaign’s musical selections, both of Clinton’s playlists feature performers with more diverse backgrounds in terms of their race, gender, and sexuality. Taken as a whole, Clinton’s playlist reflects her interest in courting black and Latino voters, LGBT voters, young voters, and female voters.

But even when analyzed individually, most of the songs on Clinton’s playlist stick strictly to a common message of inclusivity, optimism, and empowerment. For example, Demi Lovato’s “Confident” (2015) takes on common criticisms of women as being overly confident, emphasizing the singer’s control over her life and decisions. Likewise, Katy Perry’s “Roar” (2013) shows the evolution of the singer from a quiet, polite (perhaps stereotypical) girl to a woman ready to make herself be heard, to fight and, importantly, to win. Clinton’s inclusion of “Glory,” from the film Selma (2015), extends these messages of optimism and empowerment specifically to people of color.

The Clinton campaign’s reliance on “Fight Song” is not only a reference to her challenges or status, however, but rather an invitation to her supporters to feel empowered to improve their lives—with her.

Perhaps the most commented upon song Clinton uses is also one of the songs she plays the most: Rachel Platten’s “Fight Song” (2015). Clinton campaign rallies often feature “Fight Song” both before and after her speeches—rumor has it that reporters and Clinton staffers alike have tired of the song. Similarly to “Roar” and “Confident,” “Fight Song” features a female singer whose life is a struggle, but who knows she is capable of greatness: “I might only have one match, but I can make an explosion.” For Clinton supporters, the song demonstrates Clinton’s grit, or her ability and willingness to fight for families, immigration reform, black lives, the environment, etc., despite—according to her supporters—unprecedented levels of scrutiny and even misogyny. On the other hand, critics of Clinton explain that the song’s lyrics “describe a previously silenced underdog who’s finally willing to stand alone, no matter how unpopular her stand might be”; for them, Clinton is powerful, she’s political experienced, and she’s never been in danger of being ignored—and her use of the song further underscores her disingenuousness.

The Clinton campaign’s reliance on “Fight Song” is not only a reference to her challenges or status, however, but rather an invitation to her supporters to feel empowered to improve their lives—with her. “Fight Song” was Rachel Platten’s break out song after more than a decade struggling through temp office jobs, playing empty clubs, and receiving rejections from record labels. The campaign’s reliance on the song reveals not only Platten’s public support of Clinton (and therefore a hope that Platten’s fans will support Clinton), but Clinton’s support of Platten and other young women attempting to succeed in life.

After a year of campaign rallies using “Fight Song,” actress Elizabeth Banks introduced a new music video for “Fight Song” on the second night of the Democratic National Convention (July 26, 2016). Political scientist Glenn Richardson argues that this new video transforms the song into a “universal anthem” more effectively than did Clinton’s partnership with Platten alone.[9] The video features Banks, Platten, America Ferrera, Jesse Tyler Ferguson, Kristin Chenoweth, John Michael Higgins, Sia, Renee Fleming, Jane Fonda, Connie Britton, Eva Longoria, Idina Menzel, Mandy Moore, and more celebrities, as well as non-celebrities. Throughout, the celebrities take turns singing an a cappella version of the song (a reference to Banks’s 2015 directorial debut, Pitch Perfect 2), appearing on the screen in equal sized frames that continually change as more people join in the song. The collective star power itself is compelling (particularly when considering Trump’s pre-RNC claims that the RNC would be star-studded), and the inclusion of non-celebrities is moving, but these stars’ willingness to share the stage together, Richardson argues, shows a move away from Clinton and “toward the millions who will vote for her.” Ultimately, “Fight Song” shows who stands “with her,” while simultaneously showing Clinton herself standing with Americans more broadly.

In the end, song choices very rarely hurt candidates; as Gorzelany-Mostak argues, campaign music “is very much about speaking to those that are already in your camp, and isn’t a conversion tool.” In other words, there is little chance that the Clinton campaign’s over-use of “Fight Song” or the Trump campaign’s seemingly disorganized collection of songs will turn voters away. Campaign music is most powerful when it unites and excites supporters. Because it can create a community of people sharing similar beliefs, music has the potential to assist in transforming supporters into voters.

[1] Many thanks to Elizabeth Dister for her thoughtful comments and suggestions.

[2] Dana Gorzelany-Mostak, “Keepin’ It Real (Respectable) in 2008: Barack Obama’s Music Strategy and the Formation of Presidential Identity.” Journal of the Society for American Music 10, no. 2 (2016): 114.

[3] Simon Frith, Sound Effects: Youth, Leisure, and the Politics of Rock ’n’ Roll (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981), 123.

[4] However, Trump has (unsurprisingly) been vague about what period he means. The New York Times offered an analysis of when Republicans and Democrats believed America was greatest: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/26/upshot/when-was-america-greatest.html?_r=0

[5] Michael Schaller, Reckoning With Reagan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 180.

[6] Michael Heale, Ronald Reagan and the 1980s: Perceptions, Policies, Legacies, ed. Cheryl Hudson and Gareth Davies (London: Palsgrave MacMillan, 2008), 250.

[7] Gil Troy, Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 12.

[8] Interestingly, Reagan’s son, Michael Reagan, stated June 6, 2016 that the 2016 election would “most likely…be the first time if my father was alive that he would not support the nominee of the GOP.” (Twitter: @ReaganWorld)

[9] Glenn W. Richardson, Jr. “Trial, Transformation, and Redemption: Hillary Clinton, Elizabeth Banks, and Women in Competition—Popular Culture and the Audiovisual Transformation of My “Fight Song” into Our “Fight Song,” Trax on the Trail 13 September, 2016: http://www.traxonthetrail.com/article/trial-transformation-and-redemption-hillary-clinton-elizabeth-banks-and-women-competition