Bill Watterson’s Wisdom Literature

February 24, 2024

Once upon a time an artist made something entertaining but true about life, friendship, and imagination. The medium he used to communicate was often not taken seriously, and the money men tried to dictate his and everyone else’s design and content.

Many readers found it remarkable that he used his “comic,” which portrayed the adventures of a little boy and his stuffed tiger, to ask big questions, such as, “Why did that little raccoon [in the boy’s care] have to die? He didn’t do anything wrong. He was just little! What’s the point of putting him here and taking him back so soon? It’s either mean or it’s arbitrary, and either way I’ve got the heebie-jeebies.”

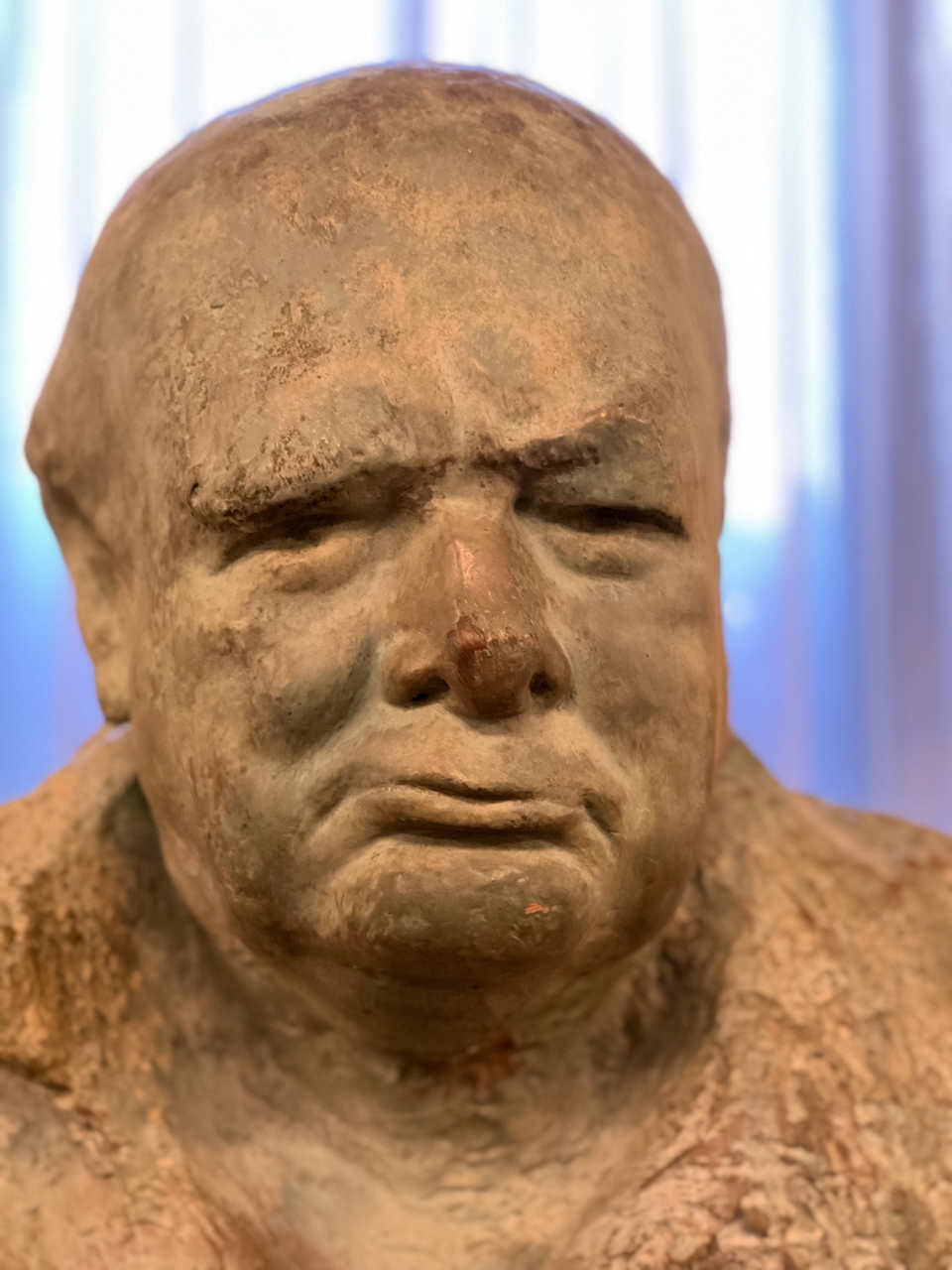

He also commented on art itself in the voice of that kid with a cowlick: “This piece [a snowman] is about the inadequacy of traditional imagery and symbols to convey meaning in today’s world. By abandoning representationalism, I’m free to express myself with pure form. Specific interpretation gives way to a more visceral response.”

“This sculpture [another snowman] is about transience. As this figure melts, it invites the viewer to contemplate the evanescence of life. This piece speaks to the horror of our own mortality!”

The artist, Bill Watterson, famously stopped drawing Calvin and Hobbes when it was still much loved and (infamously, in the estimation of the money men) refused to allow “merchandise” to be licensed with his characters’ images. In the documentary Dear Mr. Watterson, actors, artists, and business people marvel at the integrity of that decision and make conjectures about the hundreds of millions of dollars lost by it. But as Bill Amend, creator of the strip Foxtrot, says, “[Calvin and Hobbes] will be remembered in the ‘proper way,’ which is based on the work and not because there’s still Hobbes dolls for sale at Target.”

The strip ended in 1995, and Watterson was not seen or heard from much since—until last year, when he and caricaturist John Kascht published The Mysteries, a (very) brief graphic novel.

The Mysteries takes the long view. Its publisher calls it a fable, but it is more a parable, about specific but anonymous humans who live in a dark, medieval time. They aggressively enter the modern world, thinking they have a handle on what has made them afraid ever since forests have existed, then rapidly fly out the other side to whatever comes next. Because the story (which is Watterson’s) thinks in eons and at the scale of the universe, only the Mysteries “lived happily ever after.” The story is not good news for us. It is not not good news; it just is, calm as oblivion.

In one of Watterson’s simple, black-and-white strips from a midweek newspaper all those years ago, Calvin tells Hobbes, “Mom says death is as natural as birth, and it’s all part of the life cycle. She says we don’t really understand it, but there are many things we don’t understand, and we just have to do the best we can with the knowledge we have.”

Watterson echoes this sentiment in a promotional video for the new book, Collaborating on The Mysteries. The video, made with Kascht, details their working collaboration and its (many) frustrations due to both artists’ uncompromising approaches. Watterson’s demand that the book be new and its own thing, even if that thing turned out to be an unusable nothing, recalls Calvin saying, “The only permanent rule in Calvinball is that you can’t play it the same way twice!”

Watterson says in voiceover, “Our process was appallingly inefficient, and wasteful. We were basically drawing the map as we wandered around lost. But when you’re lost, pretty much everything is surprising.”

At the end of Dear Mr. Watterson, celebrity fans talk about the final Calvin and Hobbes strip. The lads go sledding while enthusing about “a brand new world” due to the “clean start” of the New Year and the new snow.

“It’s like having a big white sheet of paper to draw on!” says the tiger.

“It’s a magical world, Hobbes, ol’ buddy,” Calvin says. They fly into the white space together, toward whatever comes next.

“Let’s go exploring!” Calvin cries.

The difficulties of process and doing the best we can with our mortality: All of this is not particularly bad news. It is not not bad news. It just is: wise.