Black History Month Note No. 2

Let’s talk about Black quarterbacks.

By Gerald Early

February 11, 2023

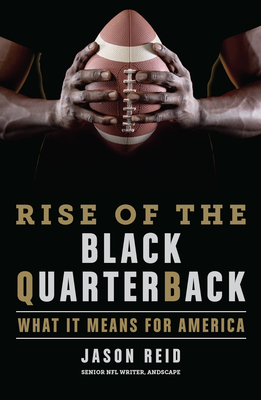

Rise of the Black Quarterback: What It Means for America

When this season’s Super Bowl combatants were decided, with both the Philadelphia Eagles and the Kansas City Chiefs boasting Black quarterbacks in Jalen Hurts and Patrick Mahomes for the first time in history, Doug Williams, the first Black quarterback to lead his then-named Washington Redskins to a 42-10 victory over the Broncos in 1988, likened the historic matchup to the 2008 election of Barack Obama as president. After reading Jason Reid’s history of Black quarterbacks in the National Football League (NFL), one may be inclined to forgive Williams’s overstatement, an indulgence he probably earned the right to express.

It was, for a considerable time, a tough climb for Blacks to gain a chance to play that position. The NFL’s intractable racism, coupled with the intractable nature of authoritarian head coaches bound by tradition about how the position should be played and how the game itself should be approached, were difficult to overcome. Institutional and structural racism combined with the conservatism of “this is how we do things here because this is how they have always been done” reminds one of the White Confederates and their perverse rationalizations and ruthless exercise of power. Pro football can, in some respects and at a certain time in its existence, be likened to Bourbon culture.

The NFL sells the quality of its competition, which is based on having the best players, and the league cannot afford to shun the best players at a particular position because of race which, after a point, is irrational, a bad business decision. There is something here for every ideology!

Black liberals and leftists might say that what has brought us to the “racial achievement” of Super Bowl LVII is the pressure of protest, rising self-awareness and an ever-evolving political self-consciousness among Blacks, growing Black political power, the unstoppable radicalization of the race that has changed how Whites can conduct business, especially in areas where the presence of Blacks is essential, such as professional football. Black conservatives will argue that rising Black income made Blacks a more powerful audience and better able to nurture and supply talent for the game; and the ineluctable impact of markets effected the change: NFL owners discovered that racist practices concerning quarterbacks were becoming too expensive to maintain and too inefficient. The NFL sells the quality of its competition, which is based on having the best players, and the league cannot afford to shun the best players at a particular position because of race which, after a point, is irrational, a bad business decision. There is something here for every ideology!

As Reid informs his readers, pro football has its “thinking” positions, “such as interior offensive line, middle linebacker, and, of course, quarterback. The players in those jobs make the initial play calls and pre-snap adjustments based on opponents’ offensive and defensive alignments. Not surprisingly, they’re usually the smartest guys in the locker room.” (61) (The NFL administers intelligence tests which Reid does not discuss.) Of these positions, the quarterback is the most prominent, the leader of the offensive unit which, of course, is the unit designed to score points for the team. Players who score are more popular, seem more heroic, more dazzling, than players who prevent opponents from scoring, at least in football, a game that strikes most uninformed viewers as being built on the contradiction of blending regimentation and chaos. The quarterback is the player most likely to be known to casual fans or even people uninterested in football. (Think Tom Brady) He is, in effect, as Reid notes, the face of the team. And if he is particularly good, he is likely the highest-paid player on the team.

The knock on Blacks being quarterbacks was, Reid recounts, “[they] supposedly lacked work ethics, lacked the intelligence to comprehend NFL playbooks, lacked the confidence to lead white men, and lacked the toughness to play through pain.” (84) This was the exact criticism that was used by the American military to maintain racial segregation and curtail Black advancement through the ranks before Truman’s order desegregating the military in 1948. In short, Black men were too dumb, too lazy, too cowardly, and too weak. Football, frankly, is a sort of warfare without weapons (consider its terminology of blitzes and bombs and strikes). A good deal of the modern game’s mentality and ethos, the style of game that became a force in American culture, was shaped by men who had served during World War II or who were deeply influenced by men who had served in that war, “the good war.” That Whites in pro football and in the pre-integrated military would see the same so-called defects in Blacks is hardly surprising.

Players who score are more popular, seem more heroic, more dazzling, than players who prevent opponents from scoring, at least in football, a game that strikes most uninformed viewers as being built on the contradiction of blending regimentation and chaos. The quarterback is the player most likely to be known to casual fans or even people uninterested in football.

Reid starts Rise of the Black Quarterback with an account of the effort to get Fritz Pollard into the pro football Hall of Fame, led by Pollard’s grandson. Pollard was a star college player, principally with Brown University. He became a pro player in 1919, never graduating from any of the many colleges he attended. Along with Paul Robeson, who became a pro player to earn money to attend law school, Pollard led the Akron Pros to an undefeated season in 1920-1921. Pollard also served as co-coach of the team, so he was not only first Black star of pro football but also the first Black coach. He was technically a quarterback in the pros (a halfback in college), but the position was not what it is today. Forward passes were rarely thrown. He was basically classified as a backfield player. Pollard left the game in 1926 and was shut out of the game several years later as the NFL (formed in 1922) stopped accepting Black players or any Black presence on the field in 1933. Pollard formed an all-Black team in the 1930s, but NFL teams refused to play the squad. Blacks would not return to the game until 1946.

Getting Pollard, who certainly deserved the honor, into the Hall of Fame was a struggle. His grandson launched the effort in 1990 and Pollard was finally voted in 2005. Part of the problem was that most journalists, the main body of Hall voters, had never heard of Pollard. They had to discover a whole new archive by learning about him in the Black newspapers of Pollard’s day. Everyone was surprised, not only in learning about Pollard’s athletic ability but how much of a crowd draw he was until the coming of Red Grange, the Great White Hope of professional football. Voters were also surprised that he served as a pro coach.

To be sure, Pollard faced incredible racism at that time. In college, his grandson recalled, “‘They shouted the N-word nonstop and threw things at him. His freshman season, this went on everywhere he played. There were always threats. The fans were awful.’” Or perhaps more accurately put, the White fans were awful.

Warren Moon, whose NFL career went from 1984 to 2000, after having played several seasons in the Canadian Football League, became the first and only Black quarterback to be inducted into the pro football Hall of Fame (2006). Reid writes of Moon’s college days, “Oddly, University of Washington fans booed throughout home games for three straight seasons in the 1970s. They did it in unison, showering the school football team in disapproval in 60,000-seat Husky Stadium. The storm of negativity had little to do with the quality of play on the field, or for that matter the team. An overwhelming majority of Huskies ticket holders disapproved of just a single player: starting quarterback Warren Moon.” (136) Moon had beaten out a popular, local White player for the starting QB job. When quarterback James Harris was drafted by the Buffalo Bills out of Grambling in 1969, “[the] hate mail he received was stunning—in both volume and depravity.” (110) Welcome to the Fritz Pollard White Fan Club! Or as the French put it, for quite a while, with Black quarterbacks, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

That Black players in the twenty-first century feel secure enough to criticize a Black quarterback because they feel that the Black quarterback has finally arrived and is himself secure is significant, something to think about in considering the complexities of America’s crossover society.

Rise of the Black Quarterback is a fascinating book, tales of hope and heartbreak, men determined to give it their all to achieve their dream and, for many years, not being given a fair chance even to try. Joe Gilliam was under so much pressure to be perfect to fight off Terry Bradshaw as quarterback of the Pittsburgh Steelers, (Gilliam won the job and had better skills than Bradshaw), that he folded, and his game came apart at the seams. The coach benched him even though the Steelers had a winning record. Bradshaw came in and the Steelers won four Super Bowls over the next six years. Who can say the decision to bench Gilliam was wrong but if Gilliam had been White would he have been given more of a chance to right himself? Gilliam eventually lost his career to a drug habit. Tony Dungy, the first Black head coach to win a Super Bowl, had been a star college quarterback but had to become a defensive back when he reached the NFL. Most Black quarterbacks who wanted any sort of career in the NFL had to switch positions, even though nearly all of them had never played the position that they were switched to and had to compete for playing time against men who had played the position most of their career. Willie Thrower (great name for a quarterback) was the first Black quarterback to play in the NFL, that is, to throw a forward pass. In fact, he threw eight of them, completing three. Reid provides the stories of such standout Black quarterbacks of the 1980s and 1990s as Michael Vick, Randall Cunningham, and Donovan McNabb (all of whom played the lion share or important portions of their careers for the Philadelphia Eagles). In looking at the Black quarterback under pressure and combatting criticism, Reid does not look at the feud between Donovan McNabb and wide receiver Terrell Owens who were both teammates on the Eagles when the team lost Super Bowl XXXIX in 2005 to the New England Patriots. Owens accused McNabb of choking during the big game. McNabb, at one point, accused Owens of committing a “Black-on-Black” crime with his criticism. The story does not quite fit the overall theme of the book, but the idea of the purpose and utility of the criticism of the Black quarterback, no matter whether the source is Black or White, seems important. That Black players in the twenty-first century feel secure enough to criticize a Black quarterback because they feel that the Black quarterback has finally arrived and is himself secure is significant, something to think about in considering the complexities of America’s crossover society.

It nearly goes without saying that there is a chapter devoted to Colin Kaepernick. Reid is right that it was disgusting how the NFL hung Kaepernick out to dry for committing no greater crime than having some principles, thinking about his civic responsibilities, and badly mangling Marxism. Indeed, Kaepernick committed no crimes at all, which cannot be said of some other NFL players in recent years. But an unalloyed admiration of Kaepernick because he is “political” is too simplistic and, in fact, I think does a great disservice in trying to understand the man, his psyche, his quest for identity, and the circumstances today that make life more difficult in some respects for people for whom many things have been done to make it easier. The left’s, nay, our worship of Kaepernick is nothing more than the standard mythologizing of the anti-hero, afraid if we do not, we are missing something, not monumental, but cool. If we have ceased to live in an age of miracles or in a world of the genuine, we surely live in an age of irony. Kaepernick is worth more than to satisfy that rather tawdry need or simply to see himself as we see him. Unfortunately, whatever may be said about the world we live in, we have never left the age of hucksterism.

Kaepernick, I suspect, must be desperate to get back to playing football. After all, it is the game he spent most of his life learning to play at an extraordinarily high level, a level attained by only a gifted few. To see his best years go to waste must be agonizing for him no matter how much hero worship he gets from leftist corporate types and the activist crowd. But I suppose that Reid must have felt that that aspect of Kaepernick is another story for another day. And insofar as the subject and approach of Rise of the Black Quarterback is concerned, he is right.

Happy Super Bowl Sunday, Everyone!