Albrecht Dürer, who went on to paint one of the earliest independent self-portraits in the history of Western art, first sketched himself with a pillow floating in the foreground. Oddly angled, the shadow of its billows cross-hatched in sepia, the pillow is a bit of a puzzle.

But when I read about his arranged marriage the following year, to a pious yet selfish woman who failed to understand him, I am glad he had the comfort of that pillow.

Few things matter more than where you rest your head. Hard synthetic foam is an abomination, and the ancient Chinese preference for hard-angled ceramic pillow boxes mystifies me. I would have stuffed a silk case with mosses and fragant herbs, or borrowed a loved one’s lap.

The sign that a romantic relationship has deepened into something that can endure? The moment one person, troubled or in pain, rests their head in the other’s lap, feeling no need to ask permission, knowing they will be soothed. Their time together has ceased to be performative; it is as much about solace as desire.

We are all pillows for one another, softening life’s rocky passages whenever and however we can. A cool pillow can ease a feverish body. A pillow from home can make a hospital stay less unbearable. Cartoonist Mike Peters travels with a little red pillow, hugging away stress. Our tenderest confidences are exchanged in “pillow talk,” in the naked, quiet moments before sleep. Only fools and newlyweds fight at bedtime. Ready to explode, we scream into a pillow. Sob into a pillow Practice kissing on one. The best fights kids can have are pillow fights, proof that you need not draw blood, only feathers.

Pillows are silly—one of several reasons Pillow Guy’s bombast was so much fun to mock. But they are also deeply personal. Bereaved spouses cradle and inhale their loved one’s pillow, catching their scent, thinking of that stubbled cheek pressed against its casing. A baby tooth must be carefully placed under your pillow, because that is a safe and magical place that is only yours.

Alas, for that same reason, some people sleep with a gun under their pillow, or a knife. Those who keep their phone there worry me even more. It is said that if you slide a coin under your pillow, you will dream about money, but who wants mere dreams? Superstitious college students stick a textbook there and hope for osmosis. Thoreau did better; he kept paper there, in case sleep eluded him and ideas flowed. Those worried about insomnia or bad dreams keep a sachet of lavender there, hoping for sweet rest.

To be pillowed, the Urban Dictionary tells us, is to be so exhausted you feel giddy, a little drunk.

Asked to name the ten most essential luxuries, I would include, though I do not have one, an eiderdown pillow, stuffed with the soft underlayer feathers, the ones closest to the body. But goose is good enough. I knew I was squarely middle-aged when I started bringing my pillow on road trips, knowing our rented bed was unlikely to have a squashable one. On our bed rests a grateful profusion of pillows: I lean a feather pillow against a firmer bolster and stick another beneath my knees; my husband uses two beneath his head and stretches his arm across a third; and when the dog is first to bed, he lays his head on a pillow and snoozes in such bliss, I found him an old one to use as his own. We do not take these pillows for granted. Choosing a new one is a first-world research project, because—and this has political and economic implications—once you have lived in comfort, you will do anything to keep it.

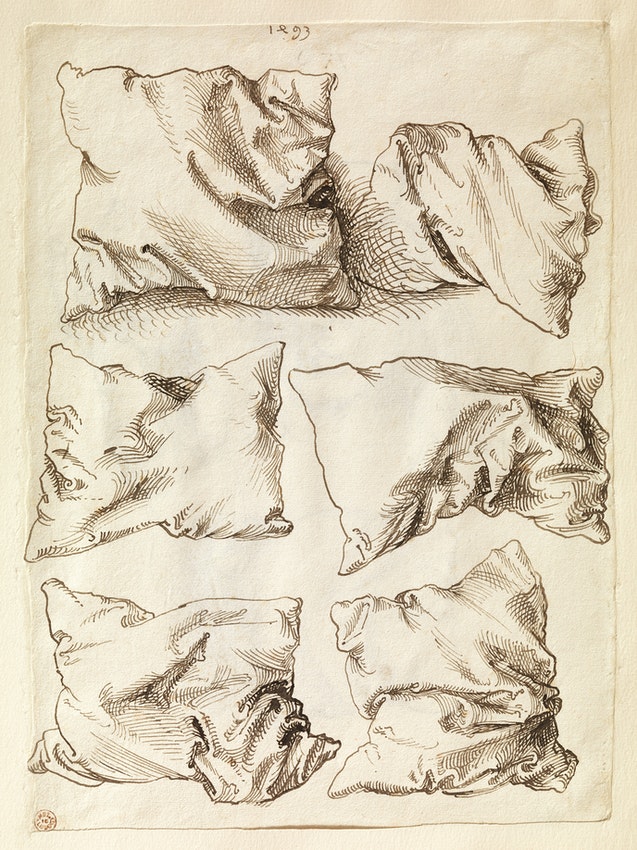

On the back of Dürer’s self-portrait are six pillows, afloat without anchor, each crumpled or twisted in its own way, as though they have yet to recover from a succession of nightmares. Art historians insist that if you stare long enough, you begin to find distorted faces caught in the folds. “This game of ‘seeing as’ can be played indefinitely,” writes Joseph Leo Koerner, “transforming corners into noses, chins, or satyrs’ horns, and creases into mouths and brows, until each pillow is animated by a number of hypothetical masks frowning, laughing, fretting, and speaking.” Heads are inside the pillows, not atop them.

I assume this is academic overreach until I spot an unmistakable eye and, below it, a wicked smile creasing one pillow’s corner. And why not, I think, swiftly changing my mind. Surely our pillows do end up containing us. They share our miseries—they absorb the cold sweat of night terrors, receive the angry punches of the insomniac, get cast aside to create space for acrobatic intimacy. All is forgiven, and they wait, dented, to be plumped back into shape and catch our dreams again.

China no longer sleeps on solid porcelain, ceramic, or bronze pillows, but it has had an arduous journey toward comfort and probably still suspects us of indulgent excess. The surrealist painter Zhang Xiaogang was a little boy when his parents were yanked away and sent to one of the “study camps” of the Cultural Revolution. Today, much of his work explores family. In one painting, a child clad in bright red lies in a drab, austere bedroom, its only softness three pillows stacked out of reach.

Ancient Japan’s Pillow Book brings everyday ease close again, as author Sei Shōnagon jots court gossip, lists what she loves or hates, scribbles poems, describes the seasons. The entries are disconnected, random as a cough-syrup dream, because pillow books are meant to be personal, not ordered for public consumption.

“My religion is my pillow for my compassion,” sings Ifrah Monsour in “I Am a Refugee.” Supporting, cradling, restoring. By all accounts (including the opinion of Goethe, at whose feet I would sit for hours), Dürer was an extraordinarily nice man, sensitive and kind and generous, noble even. I am glad he made his pillow part of his self-portrait. Glad he carried comfort with him.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.