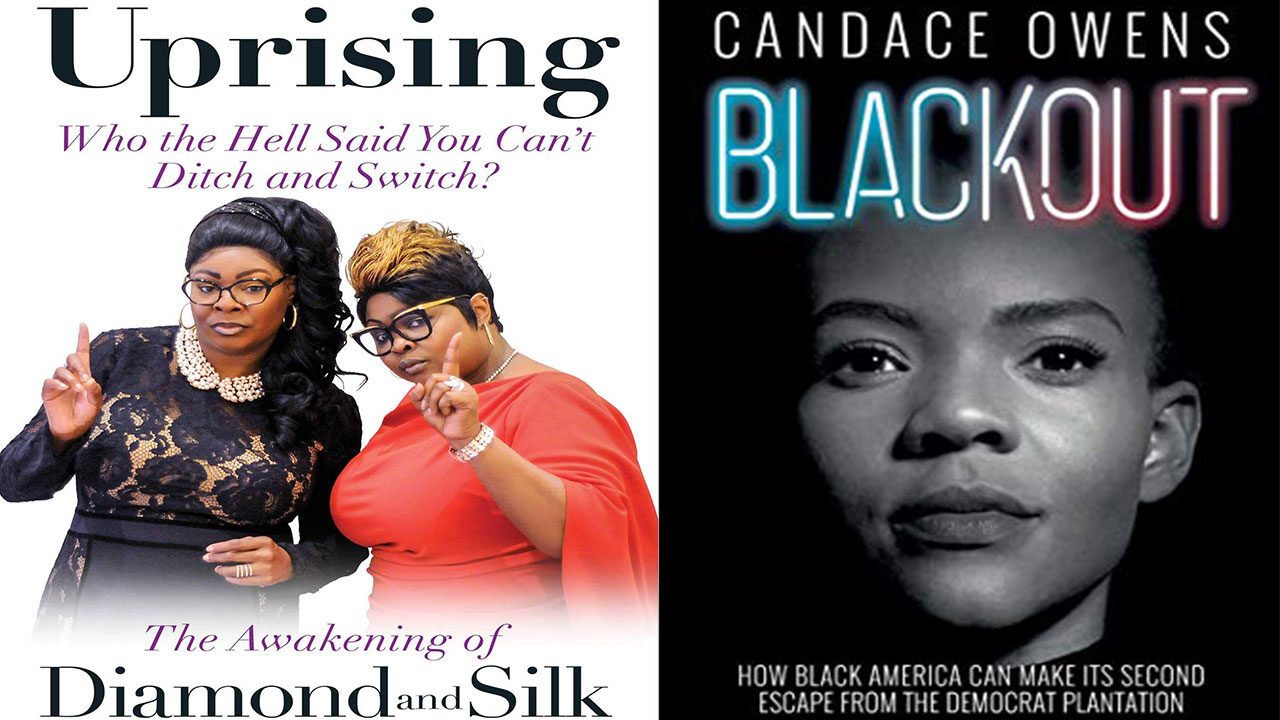

Uprising: Who the Hell Said You Can’t Ditch and Switch? The Awakening of Diamond and Silk

By Diamond and Silk (Lynnette and Rochelle Hardaway)

(2020, Regnery) 287 pages including index and photos

Blackout: How Black America Can Make Its Second Escape from the Democrat Plantation

By Candace Owens

(2020, Threshold) 300 pages including notes

- “Why Try to Change Me Now?”

… that we are at once permissive in matters of ethics, statist in matters of public policy; that we have become the second because we became the first; and that the two feed upon one another in baleful symbiosis.

—M. Stanton Evans, Revolt on the Campus (1961, italics Evans) ²

The epigraph, from White movement conservative M. Stanton Evans’s book about the conservative counter-revolution on college campuses in the early 1960s, characterizes succinctly the underlying belief of nearly all Black conservatives. Namely, post-World War II welfare state liberalism and cultural Marxism unleashed such license and moral depravity upon the United States that the Black family was loosed from its moorings, from its foundations in faith (Christianity) and in communal values (self-reliance and bourgeois respectability). The Black family ceased to believe in the honor of its own destiny.

This disruption, this disjuncture, wreaked upon the heads of a socially and politically precarious, marginalized, and persecuted group heroically trying to improve its lot, led to the unbinding of the group’s moral fiber and sense of duty. It further resulted in the group forming an attitude of entitlement to government largess, an unhealthy and unreasoning obsession with its ever-lessening oppression that colors every facet of the group’s sense of reality, and an utter lack of personal responsibility or accountability. This might be called the cult of a favored victim status, if you will, a political default that has corrupted the group’s character and debased the struggles of its ancestors. From this perspective, Blacks, prizing their resentment, their hatred, their anger, all meant to hide the shame of their inability to achieve as they ought and as they wish to, have ceased to be heroic and have become just a cauldron of grievance. So goes this view.

As Candace Owens, the most vociferous and self-promoting Black conservative currently on the punditry and social media scene, writes in Blackout, “LBJ’s Great Society initiatives were a deliberate attack on the black family. … Emboldened by the appeal of free government money, many of the pro-family advancements made by a post-slavery black community were quickly rolled back.” (Blackout 50, italics mine) And, she also writes, “… [Black Americans’] modern ideas of oppression were fathered by communism.” (Blackout 205) Those “modern ideas of oppression,” it nearly goes without saying, have corrupted Black people’s self-understanding. Blacks have become enamored of “free stuff” as the ideal good (Blackout 109). Diamond and Silk, like Owens, are social media personalities. They became acclaimed or, in some circles, notorious, when they became Trump supporters shortly after Trump announced his candidacy in 2015. They were attracted to Trump’s immigration policy. They write something similar to Owens in Uprising, about how the Democratic Party and the liberal state were “entrenching the American black man even further into dependency,” (Uprising 128) and ultimately beguiling the downtrodden with “free stuff” (129). The lure of “free stuff” was and is a way to keep Black people enslaved and undermine their will to achieve. Diamond and Silk state, “If you’re doing anything half-assed, some in the black community and some left-leaning white liberals are happy with that.” (Uprising 127)

Nowadays, it is easier to be a Black conservative among White conservatives than among Blacks generally, who despise and distrust conservatives and Republicans, but it is not necessarily easy. Across the racial divide in conservative circles, there is always suspicion about people’s motives.

This, of course, echoes the complaints of various Black conservatives—from Shelby Steele to, well, Candace Owens—that affirmative action is meant to debase Black people’s standard of excellence, to make Blacks satisfied with lower expectations of themselves, to make you as a Black feel simultaneously entitled and second-rate, privileged and an object of charity, a possessor of unearned privilege, to use a current term, that paradoxically has been purchased by your past oppression and, incredibly, your self-respect. (I remember some years ago that the late jazz critic Stanley Crouch told me he thought Blacks, except in a few areas of endeavor, wallowed in a vat of mediocrity that made Whites feel superior. “Our problems and the remedies for our problems are all meant to make Whites feel superior, even when they’re feeling guilty and contrite and are self-loathing revolutionaries,” he said.) And, at least from one perspective, the root of this pathologized tangle we call race relations is permissive ethics and statist public policy. To this extent on the nature of the failure of liberalism, it is instructive to know that White conservatives and Black conservatives think alike. It is not always the case that they do or even, at times, that they may want to.

Nowadays, it is easier to be a Black conservative among White conservatives than among Blacks generally, who despise and distrust conservatives and Republicans, but it is not necessarily easy. Across the racial divide in conservative circles, there is always suspicion about people’s motives. For the Black conservatives: Are the White conservatives, underneath their welcome, truly racist, and see us as a convenient tool? For the White conservatives: Are the Black conservatives really just opportunists and hustlers feathering their own nest or preening egotists looking to keep other Blacks out so that they revel in being special?

Earlier this year, I reviewed two books by Black Trump supporters in these pages but found myself compelled to revisit the topic of Black Trump support with these new books, in part because it is useful to consider for a moment Black conservative women. There are, to be sure, some notable conservative Black women like Kay Coles James, the head of the Heritage Foundation, Carol Swain, professor at Vanderbilt University, Deneen Borelli of Project 21, Alveda King, anti-abortion activist and niece of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Star Parker, Sonnie Johnson, and Crystal Wright, commentators. Arguably, aside from Kamala Harris, the Black woman politician who has received the most media attention this election season is Maryland Republican Kim Klacik, a candidate for Congress, who ran an ad about inner city Baltimore that excoriated the Democratic leadership of the city and became a viral hit in conservative media.

But Black women, as a group, are not known for their conservatism. They are, in fact, more likely to vote Democratic and along progressive lines than Black men. Indeed, the most famous Black conservatives are men: Larry Elder, Clarence Thomas, Thomas Sowell, Shelby Steele, Jason Riley, Walter E. Williams, to name just a few who immediately come to mind. So, Uprising and Blackout are worth thinking about in this context. Why are some Black women openly, even aggressively as in the cases of Owens and Diamond and Silk, identifying as conservative? Is it an individualized pushback against a kind of Black political conformity? Is it a new expression of Black feminism? Is it an attempt to force Black people to become more politically diverse in their identification with America’s two major parties? Is it because Donald Trump has a particular appeal to some Black people because of his attitude, his manner, his status as a political outsider, his pop-culture bona fides?

Owens heads a movement called Blexit, encouraging Blacks to leave the Democratic Party, or the “Democrat Plantation” as virtually all Black conservatives refer to the party, in part, in reference to its past connection to slavery and Jim Crow segregation and in part to its hold on the mind of the Black voter. Although Blacks, as a voting bloc, switched from Republican, the party of Lincoln, to Democratic in 1936 in support of Franklin Roosevelt, they became overwhelmingly Democratic in 1964 when Arizona U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater, a major voice of the conservative movement and considered by most Black voters to be blatantly anti-Black, ran as the Republican presidential nominee. The Democratic Party has won nearly 85 percent or more of the Black vote since then. (It should also be noted that 1964 is the last time the Democratic Party won the majority of the White vote.)

In short, Owens’s project is to change Blacks’ political orientation. This could be said about Black conservatives generally but Owens is the main voice, the Pied Piper, if you will, propagandizing for this. That is what the title of her book, Blackout, suggests: a departure. “Let us turn the lights off in the liberal establishments of America as we shut the door behind us. Let us make this blackout a reality,” are her final sentences. (Blackout 284)

Owens’s project is ambitious but not without precedent. Indeed, among Blacks, everyone is trying to change your political orientation because there is always someone who is unhappy with it, who thinks, if only you were this, your mind would be free and Black people would finally escape the thralldom of Whites, the prison of our inferior status, the burning memory of our oppression.

This is ambitious and no easy hill to climb. As Clarence Thomas points out in his autobiography, My Grandfather’s Son, distrust, outright hatred of Republicans, “[runs] deep among blacks.” When he escorted Coretta Scott King to meet his then-employer Missouri U.S. Senator John Danforth, he told her how much the senator cared “about the plight of blacks in America” and his close relationship with Morehouse College. Mrs. King simply and with distaste dismissed Danforth as a Republican, which, for her, said it all. ³

Owens’s project is ambitious but not without precedent. Indeed, among Blacks, everyone is trying to change your political orientation because there is always someone who is unhappy with it, who thinks, if only you were this, your mind would be free and Black people would finally escape the thralldom of Whites, the prison of our inferior status, the burning memory of our oppression. If you are Black, everybody is talking at you, from Communists to Christians, from Muslims to Motherlanders (Back to Africa), from activist idealists to apathetic criminals: all claim to have the cure for what ails you even if you are not aware that you are sick or if you think the cure to be worse than the disease. It is all the hubbub, the background noise, of being Black. Owens is a new chord in the noise, at this point, a minor one but that could change.

When I hear all this chatter, as I have heard it all the years of my life, I often think, I am too old. In the words of Cy Coleman’s song, “Why Try to Change Me Now?” But much to their credit, Black folk never stop trying. But change, conversion, rebirth, redefinition, this is a young person’s game.

- “… Stifling Those Who Strive”

The sellout … is (or is thought to be) a member of the family, tribe, or race. The sellout is a person who is trusted because of his perceived membership in a given group—trusted until he shows his ‘true colors,’ by which time he has often done harm to those who viewed him as a kinsman or fellow citizen.

—Randall Kennedy, Sellout (2008) ⁴

I believe wholeheartedly that Democrat politicians believe that black people are stupid.

—Candace Owens, Blackout (227)

In the days of the Harlem Renaissance, Candace Owens would have been called a striver, a Black person working hard to get ahead, trying to achieve bourgeois respectability with a college degree and the desire to live an integrated life with racial pride. (There is a section of Harlem called “Strivers’ Row.”) One example of her “striving” is how she emphasizes the strenuous effort she made to pay off her college loans, which she succeeded in doing. If I seem to be suggesting that, in some sense, Owens is, for lack of a better term, old-fashioned, it is because she presents herself that way. Like Clarence Thomas, her biggest influence was her grandfather, who rescued her family from “a run-down, roach-infested building,” from “[living] among a cluster of impoverished residents [where] fistfights, police visits, and drama were commonplace.” (Blackout 14) Her grandfather had grown up in the segregated south and had learned in that challenging environment the virtues of hard work, personal responsibility, religious faith, stern discipline, and good manners.

Owens’s strategy here is to locate conservatism as a natural component of Black life and culture, something, in effect, that transcends politics. To borrow a term from former Washington University Law professor Christopher Alan Bracey’s Saviors or Sellouts: The Promise and Peril of Black Conservatism, from Booker T. Washington to Condoleezza Rice (2008), a certain strong strand of conservatism among Blacks is “organic,” implanted in Black people’s own sense of themselves as Americans and, by and large, as people of deep religious faith. The biggest criticism of Blacks generally about conservative Blacks is that they are “sellouts,” in other words, inauthentic, tools of the White establishment, and so forth. The strategy of Owens, Thomas, and others is to argue that being conservative is ingrained in Black culture and Black life. It is how Black people see the world. It is natural.

The truth is that liberalism, Marxism, progressivism, and the like are all “White” concepts that have been grafted onto Black people’s consciousness, as Whites have essentially used Blacks as guinea pigs for their ideas. That those are the sources of the inauthentic, and it has been the influence of those ideas—in essence, White people’s political pathologies and obsessions, their own expressions of unhappiness with themselves—that has so badly damaged Black people. Diamond and Silk echo this: “Religion and God have always been an integral part of the black community and the black family. Conservative values and faith in God were the glue that sealed our hope and etched it into our very being, all going back to the days of slavery.” (Uprising 33) In this regard, the true sellouts are the liberal and leftist Blacks who have perverted Black people’s political inclinations and grounded themselves in an alien ideology. So, sometimes, Black conservatives and Black cultural nationalists think alike. (The reverse side of this coin is that Black liberals and radicals accuse Black conservatives of being sellouts, being used by White conservatives as a disguise for the inherent racism of American conservatism and maintaining a racially perverse status quo.)

The strategy of Owens, Thomas, and others is to argue that being conservative is ingrained in Black culture and Black life. It is how Black people see the world. It is natural. The truth is that liberalism, Marxism, progressivism, and the like are all “White” concepts that have been grafted onto Black people’s consciousness, as Whites have essentially used Blacks as guinea pigs for their ideas.

It is this “organic” formulation that gives Black conservatives their only hope of truly converting some significant number of Black people to their cause. Conservatism must be rooted in race pride, not race surrender, a combination of filiopiety, jeremiad, and deliverance. Blackout, in other words, is a Black civics book, an old-fashioned quest for a useable past. Owens speaks of Blacks “… [making] a return to our conservative roots.” (Blackout 39) Do not let down your ancestors, you pampered, bratty Black youth of today, with your pointless, irresponsible radicalizing, your whining, and your sloth. Owens mentions the struggles of earlier generations of Black folk at every opportunity. (In this way she sounds like the scolding Black schoolteachers I had as a child who kept reminding you not to let down the race.)

Of course, the book rehearses all the usual stuff and statistics that Black conservatives spout about White police killing Blacks (rare, Blackout 170), about Black underachievement in school (bad public schools, Black student self-sabotage, weak Black families, Blackout 140-151), about the rot of welfare (destroying Black families, undermining Black men, Blackout 50-58), current Black popular music (the declension of a rich art form and Black people’s taste, Blackout 223), the lingering impact of slavery on Blacks today (nil, Blackout 239) and the like. The last point might make readers wonder how can liberal government programs of the last sixty years, bad though they may have been, have had such a devastating impact on Blacks in all aspects of their behavior but a totalizing system of complete oppression and utter social degradation like slavery that lasted for a few hundred years, and that deeply influenced the political structure and philosophy of the country, has virtually no lasting effects now. That formulation, to be sure, is curious! This is especially true in light of the Black conservative’s insistence on calling the Democratic Party a “plantation” and that it was the party of slavery. Apparently, Black people can and have, in most ways, escaped the legacy of slavery but not the Democratic Party! (You can read a complete list of Black conservative beliefs here.)

Indeed, Owens says that nearly all Black problems can be solved by the return of the Black father to the household. (Blackout xiv) It is the absence of fathers that has undone the Black family and the destruction of the Black family has led to all other Black problems. Black people need to marry and stay married. And fathers need to rear their children. Simplistic and reductionist, critics will say. But the naïveté of this answer is also its beauty. It is, after all, easier for people to get married than it is to have a total revolution. And who is to say that the ultimate result of the former would not be as good, if not better, than the latter, especially considering the track record of revolutions? Also, timing is everything: Every Black conservative has pointed out that Black out-of-wedlock births began increasing rapidly in the 1960s at the time social welfare programs and the War on Poverty became significant forces in urban Black communities. Black poverty rates went down dramatically between World War II and the 1960s, but stalled after that despite increased government spending to eradicate poverty. Hmmmm. Is it really easier to get out of poverty through marriage than by government social services? Inasmuch as Owens sees marriage as the passage to adulthood and responsibility, Blackout, in short, becomes a manual teaching Black people how to be proper citizens of the country in which we live.

The germane challenge to pose to Blackout is the flip side of the question that conservatives pose to liberals and progressives. The conservative question is: Is there any limit to the amount of money you are willing to spend on any given social program before finally acknowledging that you are wasting money and pull the plug on it? Is there a point where spending more money on social problems is clearly neither the moral nor the practical answer? Owens writes, “Welfare is the largest expenditure in the federal budget—more than $1 trillion, yearly—with absolutely no empirical points of success that warrant its continued existence.” (Blackout 54) The question, then, for Owens and her ilk is: In reducing Black dependency, how far back would you roll back welfare and social programs? Benefits only for widows and orphans but not for single, unwed mothers and their children? Benefits only for a small portion of the disabled who obviously cannot work in any capacity? The elimination of federal funding for education? The elimination of public housing? Separating Black people on the basis of being “worthy” or “unworthy”? What is the limit of reduction that must be reached to end dependency? Would eliminating all of it end completely the pathology of dependency? Is Black conservatism nothing but a quixotic attempt to bring back Victorianism?

Both women [Diamond and Silk] have managed to persevere and so, in many respects, Uprising, as it reveals the personalities and close relationship of these two sisters, is a more interesting and less preachy book than Blackout.

Diamond and Silk, sisters, are a bit too working-class in their origins to be considered “strivers” in how that word has been used historically among Blacks. But they were and are hard-working women, learning the weaving trade and then attending beautician school. Their parents were religious and, at times, unsuccessful but persistent small business owners. Diamond had a baby at sixteen and suffers from a blood disorder that, at one point, nearly killed her. Silk had problems with going to school and with her family that eventually led to her living for a time with relatives in another state. But both women have managed to persevere and so, in many respects, Uprising, as it reveals the personalities and close relationship of these two sisters, is a more interesting and less preachy book than Blackout.

The women started using social media to post their opinions after they were laid off from their weaving jobs as more Mexicans began appearing in working-class jobs in nearby factories and farms. As Diamond puts it, “Companies were laying off regular Americans, especially black Americans who had worked there faithfully for ten or twenty years, and they brought in these illegal aliens for cheap labor.” (Uprising 69)

This led the sisters to support Donald Trump, who said he was going to change NAFTA, which Diamond and Silk blamed for their dilemma. They announced their endorsement as part of their regular stream of social media commentary. It made them instantly much more famous than they had been and, naturally, created many more critics and enemies as well. The women came to the attention of the Trump campaign, were invited to a rally, met Trump himself, who admired their spunk, and soon they were fixtures at Trump events: debates, general rallies, women’s gatherings.

What they liked about Trump was his plain-spokenness: Diamond writes on hearing him announce his candidacy, “It was like, finally, I understand exactly what this man is saying. He’s not using these big words. He’s just saying it, and we, the American people, all could understand it.” (Uprising 93) The sisters themselves are quite plainspoken, “downhome girls,” you might say, which is what gives their book its charm, its authenticity, and is perhaps the quality that attracted Trump to them. They seem like very everyday Black women, too ordinary and too downhome for some of the middle-class Black Republicans they meet later. (Uprising 167-168)

Uprising is another sort of civics book. … It is perhaps a fable about how Black people truly believe in the myth of America and in its promise. It is about how much they want to be a part of America and not in a constant fight or in constant opposition to it.

What really impressed them was when, at a particular rally, Trump invited them to join him on stage and said he hoped they had “monetized” their video commentary. (Uprising 126) He expressed the hope that they would become very rich. They felt both inspired and respected by this. As Diamond writes: “When Donald Trump said, ‘Make America Great Again,’ it was not an invitation to white people to take over. It was an invitation for all Americans—all—to dream something big in your life, go after it with hard work, and be as great as you can be. That’s the American dream. And that goes for black, white, Hispanic, Asian, or any other American citizen.” (Uprising 131) Silk continues: “That’s why it was so good to hear a billionaire telling us, ‘I hope you’ve monetized this.’ Donald Trump’s message was just the opposite of the Democrats’ invitation to a permanent pity party.” (Uprising 132)

Uprising is another sort of civics book. (The “Ditch and Switch” subtitle is about the sisters’ information campaign to get people to change their party affiliation so that they could vote for Trump in the 2016 primaries.) It is perhaps a fable about how Black people truly believe in the myth of America and in its promise. It is about how much they want to be a part of America and not in a constant fight or in constant opposition to it. It is the common view of Black liberals and leftists that the Black experience is understood only through the prism of “resistance.” And while resistance is an important dimension of Black American life, to emphasize it at the expense of other dimensions of how many Blacks see their American experience is to distort who and what we are.

Black people have not only hated White people and opposed them, they have liked them too, in some cases even loved them. They have, in many instances, believed in the greatness of this country more than Whites have. Black people have always wanted to be Americans, not White, but Americans. For them, to be an American was not to be White but to be a lush possibility, to be anything. America has always been the land of self-improvement. It is White America that has let Blacks down in this aspiration, thwarted this belief. And many Blacks have grown weary of being outsiders and having to adopt the attitude of the outsider, of always being self-conscious. In this respect, the dissatisfaction that Whites have with this country and that Blacks have is fundamentally different. And understanding that difference is very important. Not understanding it may explain why White liberals and leftists do not appreciate or even wish to recognize the nature and compulsion of Black people’s version of conservatism, which means, to that extent, they do not understand Black people at all. Any Black person, no matter his or her political inclination, knows what this conservatism is because sometimes we have all felt life this way.