The Death of a Tavern Keeper

By Chris King

September 13, 2024

It is often said that when an elder dies a library burns down. It could also be said that when a tavern keeper dies a tavern burns down. So many moments of fellowship, of shared music and drinks, that would have happened now will never happen—they vanished before they could exist.

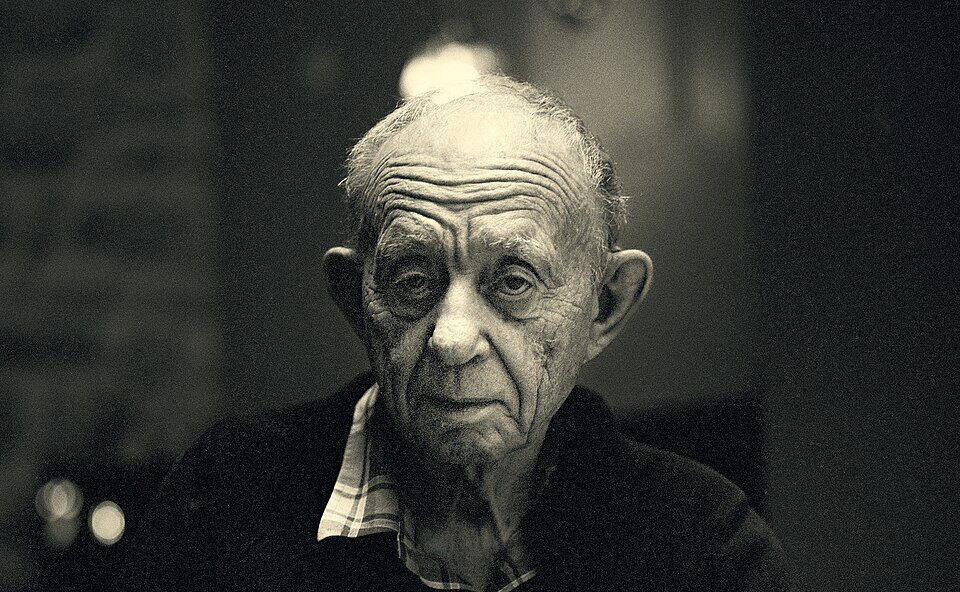

Jacobsmeyers Tavern is little known outside of my hometown of Granite City, Illinois. When its longtime proprietor Bobby Kirksey died on February 14, 2024, I was surprised to see a moving tribute to Bobby and his tavern written by Thomas Crone, a veteran St. Louis writer still eyeing his home region lovingly from his adopted new city of New Orleans. Crone remembered Jacobsmeyers as a gritty hipster haven in a rugged steel town just across the Mississippi River, where one might be surprised to find an incipient microbrewery, a batch of house hot sauces made from locally harvested peppers, or a surprisingly good local rock show. Crone also works in the tavern-restaurant business, so he would talk shop with Bobby, enjoying the candid, weary advice Bobby dispensed quietly from behind his ruddy, half-lidded eyes.

I grew up with Bobby Kirksey in a vast circle of interlocking friendships. Though we were never best friends, “Kirksey” and my last name of “King” lined up alphabetically, so we saw a lot of each other in class and quite a bit outside of class. We played some of the same sports—he pitched while I fielded third base—partied with many of the same friends, and would come to share an interest in playing rock and roots music.

I was a latecomer to playing music after an adolescence of rabid fandom and imaginary over-involvement in the idea of starting bands and making records. Bobby had the benefit of a musician father, also named “Robert” though known as “Dale,” something I discovered only at Bobby’s funeral. For Bobby it was always “my old man,” and the most often trotted out anecdote consisted of Bobby picking up bluegrass guitar at the knee of the old man and then fishing the roaches of his joints out of the ashtray.

When Bobby bought Jacobsmeyers—already a legacy tavern in Granite City—he made it clear to his musician friends that his tavern was open to us. He meant it. By the time Bobby was a tavern keeper, I was a traveling rock musician, and by the time I settled back down in St. Louis after a sojourn editing a magazine in New York, Jake’s (as the bar is colloquially known) was the perfect place to book our reunion shows. Though my band Enormous Richard was based in St. Louis, we always had a somewhat rabid Granite City fan base that would cross the river to see us play at Cicero’s Basement Bar. I thought it would only be fitting for what St. Louis loyalists remained to cross that same river heading east, now, and see us on our ur home turf. Thomas Crone encountered Jacobsmeyers Tavern initially as a venue for an Enormous Richard reunion show.

I must have booked 750 rock shows with 200 club owners over the years, and it was never easier than it was with Bobby. If no private event had been booked at Jake’s for the date I wanted, we were on, with no discussion of what money would change hands. Bobby never charged a cover at the door—something unthinkable in Granite City— and I doubt our gigs ever brought him much business above his usual weekend bar ring. For thirty-five years, Jake’s was literally the only place everyone I knew in Granite City ever thought of going to have a beer at a bar. However little money our band genuinely had earned, at some point near the end of the night Bobby would surprise me with a wad of cash—more than we had earned or that he could spare, but he would disappear as fast as he had surprised me, and the transaction was final.

The last time I saw Bobby, no surprise, it was for a booking at Jake’s. This was not a gig, but rather a guitar circle and potluck to commemorate the first anniversary of the passing of a dear mutual friend, John Kindle. As always, whenever there was an idea to convene something in Granite City, Jake’s was the first and only thought for venue, and, as always, Bobby was effortless to work with. Though we were in the throes of tightly contested NFL playoffs, Bobby was happy to host us and to deal with the mess that comes with a potluck—a mess with no profits to the house.

Jake’s had long since given up the ghost of being a microbrewery, and Bobby also had quit stocking unusual beers when the Granite City faithful always wanted the same array of predictable pilsners. Knowing all that and my penchant for craft ales, Bobby always told me to bring my own beer to his bar. As another silent agreement in a friendship where almost everything went unsaid, I always brought enough beers to share with Bobby, and his barmaid tolerated me sharing space with her behind the bar as I worked through my private stash.

My very last memory of Bobby was lining up in front of him one each of all my leftover beers I was taking away when I left the John Kindle memorial. I am sure I thanked Bobby, though I was not in the habit of remembering what few things we said to one another, expecting decades more of the same. I am equally sure he said farewell to me using the sobriquet “Bro Cat,” his private deconstruction of my hometown nickname, “Brother Dog” or “Brodog.”

After Bobby passed just a month later due to a bacterial infection of his heart, I heard that mutual friends thought he had looked pretty bad at John Kindle’s funeral the year before. I thought everyone had looked pretty torn up at Kindle’s funeral—and not much better a year later at his memorial. Other friends heard Bobby say at Kindle’s funeral that it should have been him in the casket. Twenty years before, Bobby had survived his first major heart event. Heart valves had been installed surgically that became infected and got him terribly sick, a harbinger of the medical condition that would end his life far too early at the age of 57.

I was aware that Bobby’s lust for life had been waning somewhat, though I associated that with our phase of life, when middle age starts to turn into the next thing. I knew Bobby had been wanting to sell his tavern and not finding a buyer, though I have never known a tavern keeper who did not, at times, fret that they wanted out. Bobby had groused about the burden of his bar as long as I had been booking shows with him, so I just assumed that this pattern would continue—Bobby graciously booking my shows at a tavern he wished to unload.

Bobby’s last and most serious girlfriend Brigitte Kittel was another old friend in our large friendship circle (*). She had lived with Bobby and helped out at Jake’s, so she knew the tavern from the register side, and not just as a privileged interloper drinking his own free beers from the cooler.

“I saw the other side of it,” Brigitte texted me after Bobby died, when we were all mourning Bobby and Jacobsmeyers—“the late hours, the daily drinking to the point of some level of inebriation, most of the time drunkenness, the stress of broken equipment, escalating power bills and liquor costs, thieves, unreliable staff, gambling addicts, meth heads, a deteriorating neighborhood that affected his bottom line. I would have given anything for him to have walked away.”

Brigitte worked out her feelings in a poem called “Dirge,” excerpted here, that provided an emotional autopsy of Bobby and his tavern.

Sticky floors keep you stuck in one place

High

Backed by a body on a broken stool

Behind a bar-ricaded

Protective moat

So you don’t get too close

Crowded loneliness

Just put it on my tab

The oasis is a mirage

An optical illusion

An attractive siren who sings and lures you

On the rocks

Extra salt

No lime

Make it a double

Cutting corners

Corner taverns

Leaking valves

Your playground is your pay stub and your Playmates pay the power bill

Requiem offerings

Go in the tip jar

On the day of Bobby’s funeral, I texted yet another lifelong mutual friend a short video clip of a glum version of myself, Bobby’s buddy, Bro Cat. I looked despondently into the tiny camera on my cell phone and said, “Can you pay your last respects to somebody when you never paid your first respects? Bobby was the greatest smartass I ever knew. It had never occurred to either one of us to ever be respectful.”

Only in his last years, with that growing sentimentality we often see in aging men, did Bobby become anything other than the consummate smartass. I remember fifty years of his scraggly beard, half-lidded eyes, and razor-sharp tongue. It is the fate of most situation humor to be forgotten—it emerges in a particular moment, has little legs beyond that context, and the memory fails to hold onto it. Since I never had Bobby’s wit and cannot reconstruct his brand of devastating one-liners, I prefer to remember Bobby in his other dominant mode: a covert yet highly observant silence.

The bill of a ball cap obscured the eyelids that hid almost all of the eyes, the beard masked the face, but if you got close enough—an approach that risked some smartass zinger from Bobby, tied to what you were wearing, or the way you were walking, or whatever Bobby had been watching you do from across the tavern—you would see those tiny fragments of eyes moving everywhere and seeing everything.

“I drove by Jacobsmeyers yesterday,” Brigitte texted me days after the funeral. The tavern that Bobby had failed to sell when he was alive had sold after his death—some version of Jake’s would survive Bobby after all. “The new owner has taken down the multi-colored lights that crisscrossed their way above the beer garden,” Brigitte wrote. The tavern had not burned down but would never twinkle in the dark quite the same.

Bobby and Brigitte fell in love under those now-downed twinkling lights ten years ago. They both served on the planning committee for the thirtieth reunion of the Granite City High School Class of 1984, with many events to be held, of course, at Jacobsmeyers. “We would meet up and sit outside under the lights at Jake’s and pretend we had something of great importance to discuss,” Brigitte wrote. “It wasn’t long before we realized that maybe there was more to us than event planning and day drinking.”

Brigitte stipulated a make-or-break make-out session as a kind of audition. “I told him if he was a bad kisser we could not be romantically involved,” Brigitte wrote, “and he had to promise me we would continue to stay friends regardless of the results of the make-out session. I was very concerned going in about the scratchiness of his beard, but he assured me it was soft as he did condition it daily.” They—and their lips—met in the beer garden at Jacobsmeyers. “We made out,” Brigitte remembered. “His lips were soft. But not nearly as soft as his well-conditioned beard. And all I can think about now is that summer and how all the beautiful lights are gone.”

Brigitte Kittel and friends will celebrate Bobby Kirksey with Bobtoberfest on Saturday, October 12 at Jacobsmeyers Tavern, 2401 Edwards St. in Granite City, Illinois. Confirmed musical acts include Scott and Mechelle Smith, Jared Unfried from Hideous Gentlemen, Casey Ashby from Doctor Martin’s Flannel Brigade, Ed Belling’s from Pik n’Lik’n, Blues “N” Grass, and Solstice. Expect even more music. Bring your instrument. Doors at 4 p.m., music at 6 p.m.

(*) Brigitte Kittel

I cannot fit into this narrative about Bobby Kirksey how I met his girlfriend Brigitte Kittel forty years before, but I drop this footnote to tell a story that richly illustrates the Granite City of our youth.

In the summer (1983) before our senior year in high school, the city offered a work program where union painters led crews of students in painting the exteriors of low-income homes pro bono. On the first day, the union painters picked their crews one kid at a time like captains drafting teams to play a game of sandlot ball. A wiry, indeed wired union painter named Lorren picked a crew that included Brigitte Kittel, a red-headed orphan named Yurkovich, and me.

I did not know the other kids because for three years they had attended Granite City South High School while I had attended Granite City North High School, two distinct institutions only being merged into one for our looming senior year. So, I did not know them, they did not know me, and Lorren knew none of us, but Lorren was a really good talent scout.

During our first break in painting our first house that morning, Lorren, a smaller man, dropped into this tiny crouch and lit a joint that he passed around to his teen crew members. “I picked all the freaks,” Lorren said, as indeed everyone partook of his proffered joint.

Then the homeowner threw open a window near us, cranked up the K-SHE real rock radio, stuck his hairy head out the window, and invited us all inside for our smoke break. The homeowner had plenty of good reefer to share. Come lunchtime, Yurkovich invited the whole crew to his house. Like any enterprising teenage orphan living under no adult supervision, he had a keg of beer on tap in his basement. The work days passed in a haze of weed, real rock radio, beer, and a modicum of house painting.

Lorren had this idiosyncrasy as a storyteller. He was eerily silent unless dropped into his tiny crouch to light a joint, at which point he opened up and told stories. His stories always began with “This guy I drink beer with”—it was never a buddy or a friend, always a guy he drank beer with—who presented a predicament that Lorren would proceed to solve for him and for all of us if we paid attention.

One day on the job, Lorren called a break, dropped into his tiny crouch, lit a joint, and said, “This guy I drink beer with. Always complaining about his wife. Every day, something new. That’s on top of the old things. Which he also complains about again too. Finally, I said to this guy, ‘Here’s what you do. Get a big cooler and some of those little plastic bags. The ones you see on the side of the road. That road crews use to bag trash. Then, you go ahead and kill her. Chop her up real small. Put her in all those little plastic bags. Better double bag it. Tie them up tight. Put all those little bags into that big cooler. You’ll need a little cooler for your beer too. Then you just drive around one night drinking your beer and dropping her off a few pieces at a time everywhere you see those little plastic bags of roadside trash.’”