Prisons, El Salvador and Us: The Way We Were

By Chris King

February 11, 2025

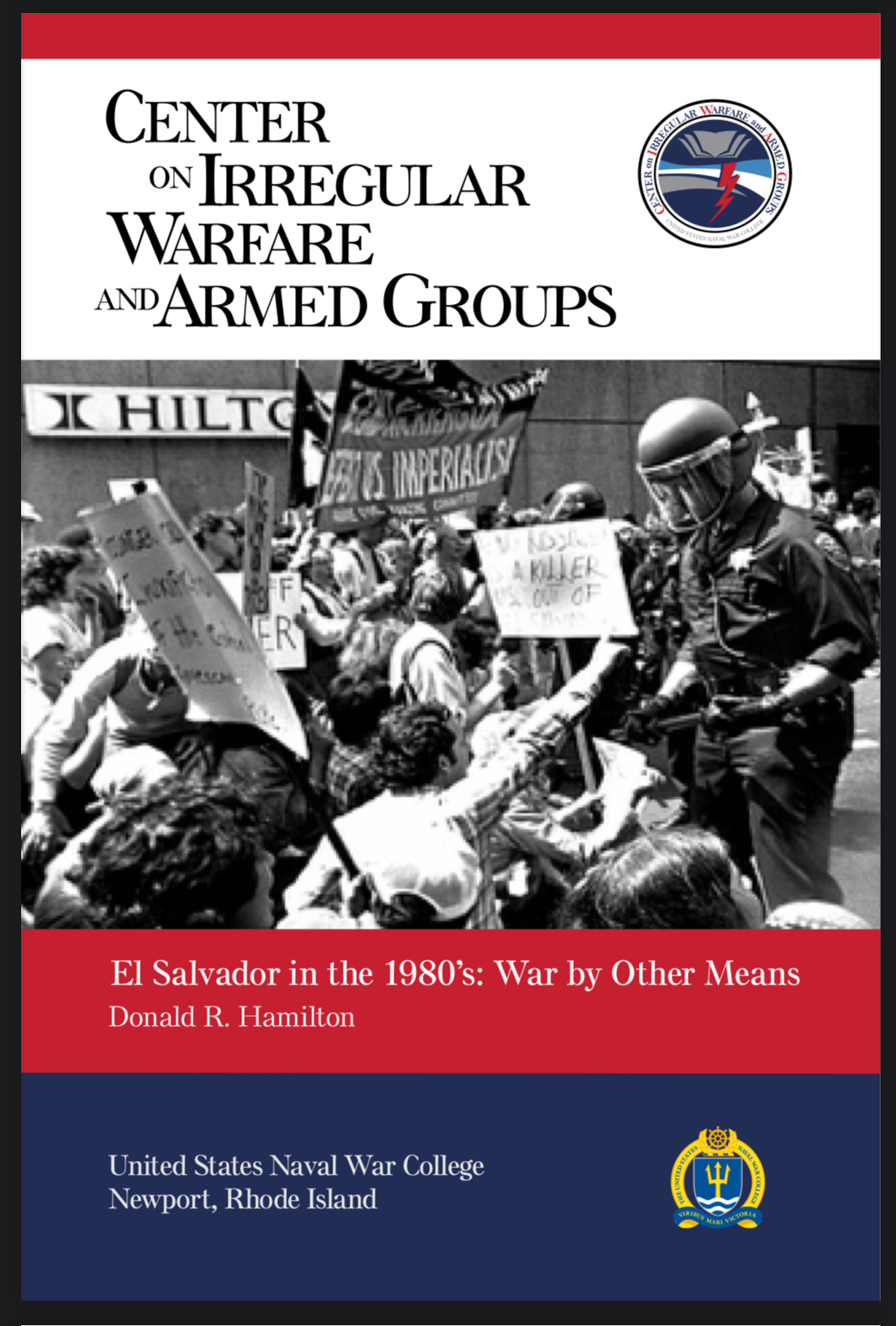

When newly sworn U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced—approvingly—that the president of El Salvador had volunteered to accept United States prisoners (including U.S. citizens) for custody in Salvadoran jails for a vendor’s fee, it triggered memories from a far distant time for El Salvador, the United States, and prisons.

It was the spring of 1985, a suitably biblical time span of 40 years ago, and I was seated with my fellow Navy ROTC midshipmen in a Boston University lecture hall for our Thursday afternoon assembly. On Thursday afternoons, we squids (as we were affectionately and dismissively known) paraded around BU’s urban campus in our dress Navy uniforms toward a lecture and group conversation about U.S. Navy values and strategy.

On this Thursday, a guest lecturer from the U.S. Naval War College walked into the lecture hall, and we all stood at attention. “As you were,” this young lieutenant said, and we all were freed to return to our seats. That ritual piece of language—“as you were”—is an unusually economical and graceful piece of military lingo. That is what a commanding officer says to someone of inferior rank who has snapped to attention at their approach. You can expand this utterance slightly to complete its meaning: go back to as you were—go back to the way you were before I walked in.

So, we went back to the way we were before this young, energetic Navy lieutenant walked into the lecture hall and started asking us questions. “What do you midshipmen think about Patrick Henry?” he wanted to know. “How about Benjamin Franklin? George Washington? What do you think about freedom fighters?”

Squids practically fought one another for their waving hands to be noticed so they could be called to attention for their hand-over-heart homilies to the greatness of our founding fathers. There was a certain patriotic one-upmanship going on.

“Okay,” the guest-lecturing lieutenant said. “What do you midshipmen think about Hezbollah? How about the Palestinian Liberation Organization? The Sandinistas? What do you think about terrorists?”

Again, there was a nearly physical skirmish of squid on squid trying to be seen and called to attention so they could issue bloodcurdling threats to these terrorist organizations in absentia.

“As you were,” the lieutenant said, in an effort to settle the agitated squids so he could proceed with his lecture. The foaming at squid mouths subsided.

“I have bad news for you midshipmen,” the lieutenant said. “George Washington was a terrorist. Hezbollah are freedom fighters. A freedom fighter is a terrorist we wish to see win. A terrorist is a freedom fighter we wish to see lose.”

He broke down the facts of war that underlie these emotionally charged labels. He explained that if you have, for example, an Army with tanks and an Air Force with bomber planes, then you fight with tanks and bombs. Getting attacked by tanks and bombs is terrifying, but it’s not called “terrorism.” It is called “war.” If you are, however, a stateless entity fighting to disrupt and overpower a state government, then you fight with what you have. You fight with confiscated arms and improvised explosives. You pull stunts such as suicide bombings and violent actions against civilians. Though no more objectively terrifying than the violence issued through tanks and bombs, these forms of warfare are known as “terrorism”—unless, of course, they are being practiced by a stateless group that we would like to see win. In that case, they are freedom fighters fighting for their freedom.

Next, he brought the point a little closer to home. Our Navy ROTC unit was run by a U.S. Marine Corps captain who was pushing all of us midshipmen to apply for summer deployments where we would serve alongside U.S. Marines. Our captain had his heart set on eventually graduating as many of us as possible into the Marine Corps, rather than the general Navy. That meant in our summer deployments we would be serving alongside Marines who had been fighting in Nicaragua and El Salvador—as yet undeclared wars that were proving messy for the officers leading them. This fired-up lieutenant said that, in just a few short years, those of us who went for the Marine Option would be leading men in battle in places just like Nicaragua and El Salvador. This could pose a problem if you did not know how to understand and describe what we were doing down there.

He said we would be leading men to do things like empty prisons and jails in places like Honduras and parts of Nicaragua and El Salvador controlled by our allies. We would empty jails and prisons of murderers, rapists, pimps, burglars, and thieves, stand them up in cheap uniforms, issue them rifles, and lead them at war against the terrorists. A major problem was that our freedom fighters, as our enlisted men knew, were murderers, rapists, pimps, burglars, and thieves. The terrorists, however, were peasants—they were the landless sons of landless farmers fighting to get their corn and bean fields back from the coffee barons. “You have to understand, we have an all-volunteer Marine Corps,” the lieutenant explained. “It’s no longer the case that a judge will say, ‘It’s jail or the service, son; pick one.’ Your enlisted men will not be criminals like our freedom fighters from the prisons in Honduras. Your enlisted men will be the landless sons of landless farmers, like the terrorists.”

I looked around at a lecture hall of squids trying to make all this make sense. I was freaking out and wanted to run screaming for the exits—as I would do right after a summer deployment on a helo carrier in the Mediterranean, where I did, indeed, serve alongside Marines who had seen combat in our undeclared wars in Central America.

The lieutenant was winding up his lecture with a pop quiz to make sure we had been paying attention.

“So, keeping all of this in mind, midshipmen, let me give you a brief quiz,” he said. “The murderers, rapists, pimps, burglars, and thieves that your men just let out of prison and issued rifles. What do we call them?”

The squids said, in firm unison, “Freedom fighters.”

“That is correct, midshipmen. Now, the landless sons of landless farmers fighting to get there cornfields back from the coffee barons. What do we call them?”

“Terrorists,” the squids all said.

“That is correct, midshipmen.”

Forty years later, we have been presented with the specter of U.S. servicemembers going into Central America— not to empty prisons looking for freedom fighter fodder—but to fill up foreign prisons with U.S. prisoners, including U.S. citizens. I have taken a vow of silence about the new presidential administration, but I wanted to record this memory for others who might want to think about the distance we have come in forty years and what it might mean. All I will say, for now, is that I long for the day when the current commander in chief of the United States’ armed forces says, “As you were,” and we can all go back to what we were doing before he walked in.