New Documentary Portrays Intrigue at Venice Biennale

October 13, 2024

“Cultural diplomacy”—the propagation of art and other culture by a government as a form of soft power—can be a tricky thing. As UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) says, “Beyond State driven policy processes, cultural diplomacy engages a wide range of non-governmental actors such as artists, curators, journalists, teachers, lecturers and students which support or amplify these processes, differentiating it from other areas of diplomacy. International art biennials, for example, rely on artists and curators.”

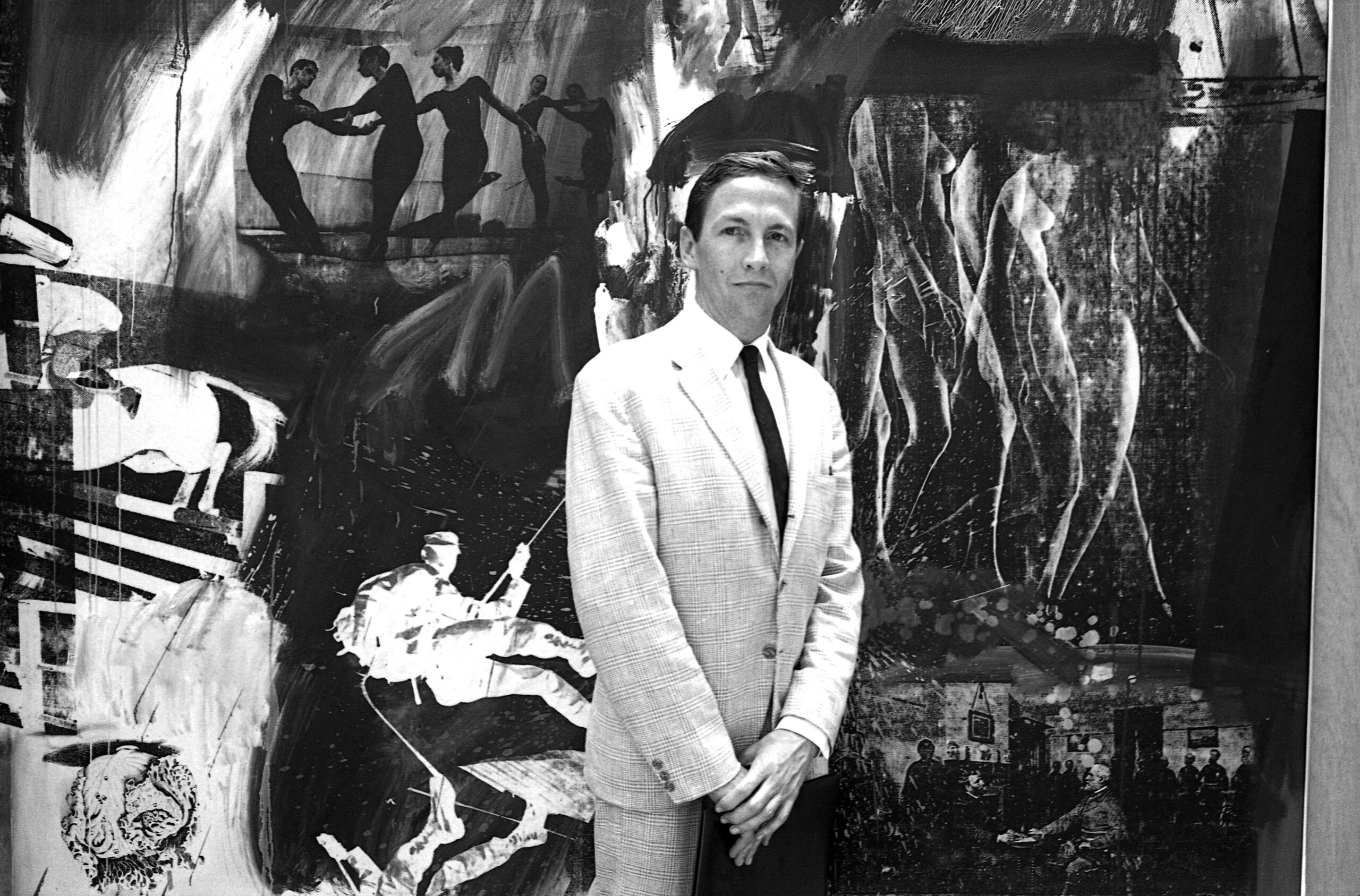

The specific mention of international biennials might point to the Venice Biennale, “the Olympics of art,” where in 1964, a small team of American “non-governmental actors,” with the help of the US government, schemed to amplify artist Robert Rauschenberg right into the grand prize. They succeeded by standard methods: lobbying well-placed tastemakers, getting someone on the voting committee, threatening to resign from said committee, increasing Rauschenberg’s visibility, and in one case stretching the rules pretty hard. His prize would become the first Golden Lion awarded to an American, causing indigestion across the continent.

A new documentary, Taking Venice, directed by Amei Wallach, tells the story of that intrigue with original footage, recent interviews, some recreations, and a snappy jazz-funk soundtrack à la Ocean’s Eleven.

The American exhibit (also John Chamberlain, Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Claes Oldenburg, and Frank Stella) and the Rauschenberg win opened the European art scene to American pop art. It was a major event in art history, but some thought the American commission’s “aggression” in the show was the final stage of American colonization. The Biennale was already “a big fiesta of nationalism,” the film points out, but the French had been seen as the dominant nationality. Christine Mabel, Director, Venice Biennale 2017, says, “Art is not just about art. It’s also about power and it’s about politics.”

The film is strongest on its portrayal of the “skullduggery” by three American non-governmental figures: Alice Denney, a longtime friend of the Kennedys; Alan Solomon, “an ambitious curator making waves with trailblazing art”; and Leo Castelli, a New York art dealer. Denney, whose husband worked in the State Department, tapped into United States Information Agency (USIA) funds—it was the first year the American government was involved in the exhibit—and got a US Air Force plane to carry the American art to Venice when no other funds were available. The three civilians profited, one way or another, by Rauschenberg’s win.

The film actually has little to say about the U.S. government’s role, beyond it insisting on “clearing” artists to be involved. Lois Bingham, Director USIA Fine Arts Division, says in a 1981 oral history used in the film, “If anyone was on the House Un-American Activities list, uh-uh, they were out. At that time, if anyone found out that we were censoring an art exhibition…we would have been finished.” The government’s goal was not to push a particular artist, or even style, but to boost American prestige abroad during what it thought of as a “cultural Cold War,” as Louis Menand says in the film. (There is often plenty to say about how the United States uses culture for influence.)

Rauschenberg, for his part, seems genuinely perplexed that anyone might have put the fix in for him. When there are glimmers, he appears rueful, resentful, angry. Much of the film watches him engage in his normal artistic life instead, including his collaboration with Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

“The Biennale thing was,” Rauschenberg says, “I don’t know…it all seemed quite unreal. It’s easier to remember what my reaction was afterwards, like months and months afterwards than what those few days were like.”

Calvin Tomkins from The New Yorker says, “This Biennale changed the way American art was perceived. It also changed Rauschenberg. He was now an international figure. Things weren’t going to be the same.”

The 1964 Biennale also proved to be the demise of the Fine Arts Section at USIA.