Never Mind Kendrick vs. Drake, Get Yourself Some Young vs. Skynyrd

By Ben Fulton

February 14, 2025

This year’s Super Bowl was two big rivalries for the price of less than one, given how handily the Philadelphia Eagles defeated the Kansas City Chiefs 40-22 and how deftly Kendrick Lamar used the biggest stage in the nation—the N.F.L. halftime show—to score another round against his hip-hop rival, Drake.

The press embraced Lamar’s show in a purr of almost unanimous praise, with The New York Times calling it “perhaps the peak of any rap battle, ever.” Never mind the shooting deaths of Tupac Shakur in 1996, followed by that of The Notorious B.I.G. in 1997, as a result of their heated East Coast-West Coast rivalry—one which also drew Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan as a mediator between the two sides, adding to the religious leader’s long list of attempted peace settlements between rap artists.

My trip down memory lane recalls with fondness the heated late 1980s beef between Kool Moe Dee and LL Cool J, in which both traded masterful barbs of rapid-fire insults without bullets flying. Even more fond are memories of reading the vinyl LP liner notes of Public Enemy’s 1988 album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, for which Chuck D and Co. gave a shout-out to virtually every rap artist and act at the time, East Coast and West Coast, without insulting a single soul. Public Enemy’s example of fighting “The Man,” and not your fellow rap artist, now seems quaint.

But whether minor bickering or mattes of life or death, what all these conflicts obscure is the long, very long, history of rivalry running through pop culture, whether punk rock, rock, pop, or hip-hop. Perhaps the sole difference between current and past rivalries is that they tended to hold more cultural, as opposed to personal, weight.

Rock from its inception was oppositional. It was a creative expression of African-American rhythm and blues crossing the segregated line to drive white youth wild with excitement and induce panic in their parents. Elvis Presley mastered the form without writing songs, while the Everly Brothers and Buddy Holly could pass for “colored” in swagger without sounding too gritty. Then a boatload of “British Invasion” bands showed how best it could be done, most notably The Rolling Stones, still the greatest White blues band of all time.

Elvis killed rock music’s promise of rebellion by joining the U.S. Army. Bob Dylan rebelled against folk-music strictures by “going electric.” The Beatles, near their collective end, rebelled against one another to go solo. With the dawn of punk, The Sex Pistols traded barbs with The Clash. With the dawn of grunge, Nirvana traded nasty looks across Seattle and abroad with Pearl Jam.

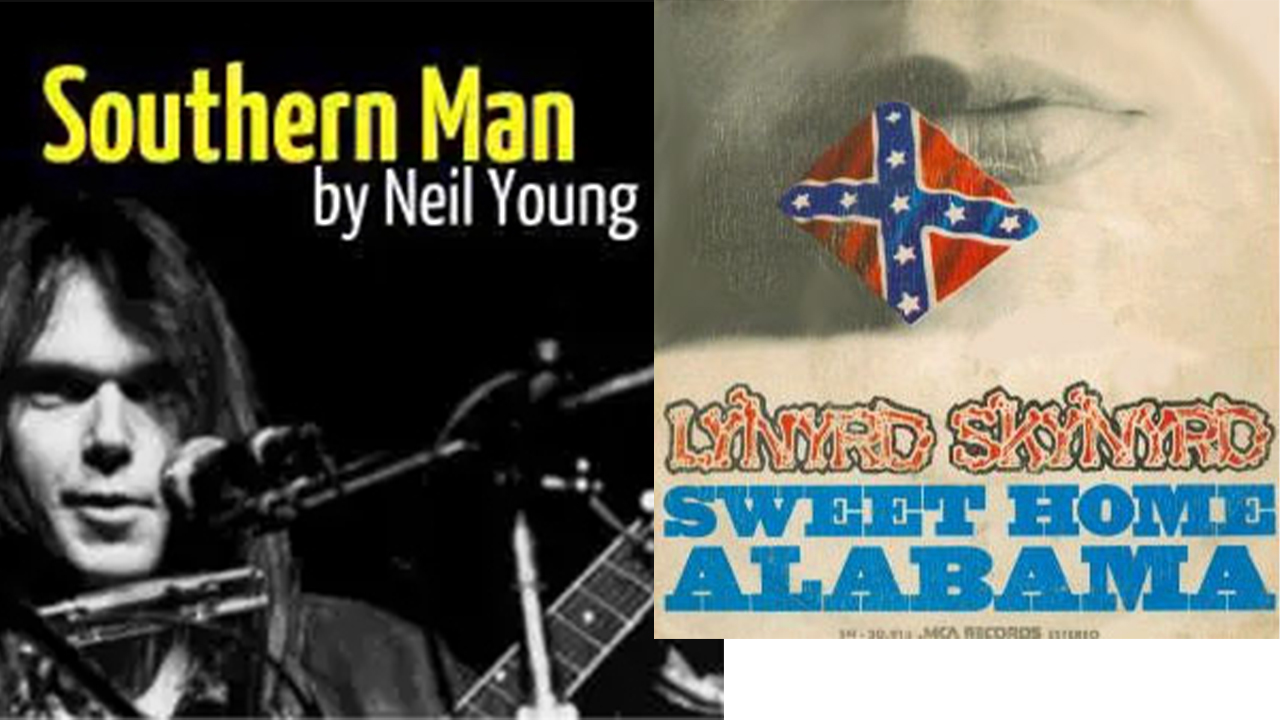

Like private companies doing battle in capitalism’s arena to produce the best products, pop and rock rivalries have undoubtedly created great music. My own favorite is the battle between Neil Young and Lynyrd Skynyrd, not because it produced songs among my favorites, but because over a long period, since at least 1973, it has helped define what among a songwriter’s chosen culture must be defended, and what is worth pillory.

Neil Young fired the first shots with “Southern Man” (1970) and “Alabama” (1971), broadsides against White Southern intransigence and bigotry. Months after Lynyrd Skynyrd answered him with Southern-fried guitar riffs and Dixie-inspired invective, fans of both Young and Skynyrd were discussing, if not debating, George Wallace, Watergate, and what it meant to exact judgment on a culture you do not belong to (Young was and remains Canadian) or be proud of a culture or region despite its fraught, even shameful, history. Decades afterward, Young admitted that his songs were overly “accusatory and condescending,” while Skynyrd singer Ronnie Van Zant acknowledged that his band’s most famous hit could have been more specific in its message than celebratory and defensive in tone. To watch various YouTube clips of the song today is to discover a rivalry slowly reconciling. One that has garnered 24 million views over ten years shows the late Van Zant, who died age 29 in a plane crash, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the cover of Young’s 1975 album, Tonight’s the Night. Neil Young showed no shame wearing Lynyrd Skynyrd’s T-shirt, which borrowed the Jack Daniels label. Thus, one of rock’s most famous “battles” became a slow-moving argument, followed by dialogue and resolution.

Drake, like Young, is also Canadian, albeit also a U.S. citizen. Unlike Young and Skynyrd, though, Drake’s and Kendrick’s intensifying beef somehow exploded into the deeply personal, as opposed to cultural, arenas of identity. With Trump’s aura of personal attacks and conspiratorial accusations of “grooming” on the political ascent once again, hurling the charge of pedophilia against your opponent is almost common enough to be tiresome. Do we really need to feed this fire with the fuel of our collective attention? From business arrangements that end in civil suits to marriages that end in divorce, we could say the vast majority of life is indistinguishable from conflict and rivalry.

What we need desperately from pop music and rap artists, and what is in short supply now, is not rivalry for its own sake and spectacle, but a sense that our favorite songs of the future might have something immediate to say beyond the context of two individual artists. Lamar’s halftime show made compelling gestures in that direction, with Samuel L. Jackson invoking “The Great American Game.” More, please. Pop culture used to speak in opposition to forces we all struggled against. It even offered us sentiments against which we might grow humble.