In and Out of the Shadow of Willie Mays

A new book on the career of a hall of fame player who played in pain but without angst

By Gerald Early

September 30, 2025

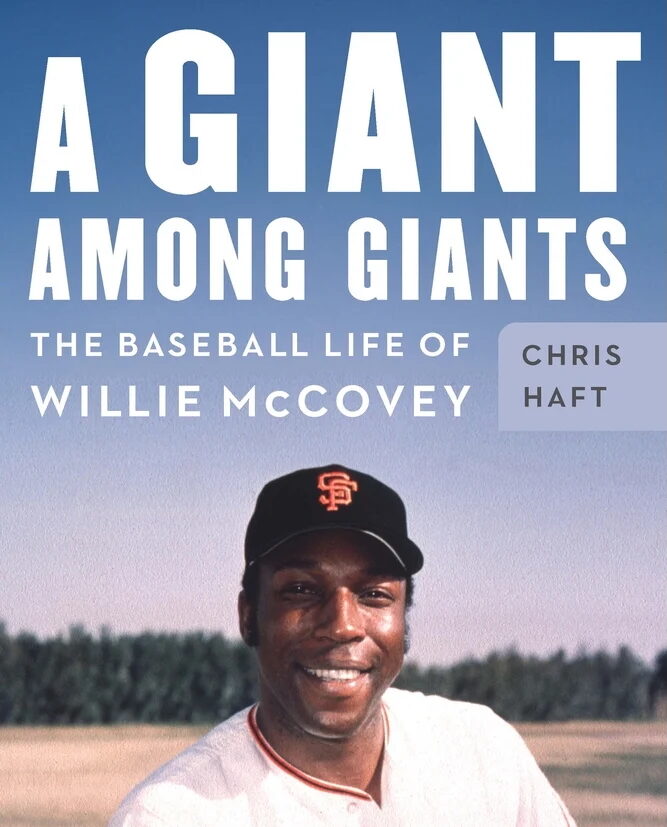

A Giant Among Giants: The Baseball Life of Willie McCovey

Hall of Famer Willie “Stretch” McCovey won the National League’s Rookie of the Year Award unanimously (all the first-place votes) in 1959, even though he played in only 52 games (in a 154-game season) for the San Francisco Giants. He had a .354 batting average, 13 home runs, a .429 on-base percentage, and a .656 slugging percentage. All astonishing numbers for only 192 at-bats. But that is the point: it was only 192 at-bats, and there have been plenty of players who were phenoms in a small sample size. For instance, McCovey would hit over .300 only one other time in his 22-year career. In his sophomore year, McCovey would hit only .238 in 260 at-bats, and both his slugging and on-base percent would be significantly lower.

Yet there was something different about McCovey that the knowing coves of baseball sensed right from the beginning. In his first game, on July 30, 1959, against the Philadelphia Phillies and their ace, future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, he went four-for-four with two triples, something more impressive, in many respects, than if he had hit two home runs. At 6 feet, 4 inches, and nearly two hundred pounds, he was a presence in the batter’s box. He looked fearsome. McCovey wore the number 44 after his homey, fellow Mobile, Alabama, native Hank Aaron of the Milwaukee Braves, who was already a star, one of the most incredible hitters in the game, so good that he seemed to radiate a sort of athletic purity, having won the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1957 with 44 home runs, 132 runs batted in, and a .322 batting average, on a team that beat the Yankees in the World Series. It took a bit of chutzpah for a rookie to take that number.

As San Francisco baseball beat writer Chris Haft writes in A Giant Among Giants, “McCovey’s arrival galvanized the Giants. His debut, which ranks among the finest in any professional sport, launched a surge of 10 victories in 12 games that put San Francisco back atop the NL standings by 3 games. ‘I kind of created a spark that resonated through the rest of the team,’ he said.” (15) That kind of player, who can change the sense of destiny of a team, is rare. That is why the baseball writers voted McCovey the Rookie of the Year. They sensed that he was not simply an excellent player but possibly a historic one.

When McCovey arrived in San Francisco in 1959, Willie Mays, arguably the greatest, most charismatic player in the game, was 28 years old, an MLB veteran of seven years, yet new to San Francisco, as the team had only moved to the West Coast at the end of the 1957 season.

The only problem for the Giants was the player who won the 1958 Rookie of the Year Award, Orlando Cepeda. In 1959, Cepeda hit 27 home runs, drove in 105 runs, batted .317, had an .878 OPS, and hit 35 doubles. Cepeda played first base. (Cepeda had 29 homeruns, 96 runs batted in, a .312 batting average, and 603 at-bats playing 148 games in the 1958 season when he was voted Rookie of the Year.) The problem was, McCovey’s best position was also first base. This would remain a problem for the Giants for several years: that two of their best hitters played the same position. To keep them both in the lineup in this era before the designated hitter, one of them had to play out of position, either the outfield, where both were, at best, adequate, or, for Cepeda, third base, which he hated and did not play well. McCovey could not play third base because he was a left-handed fielder. Left-handers can play first base, the outfield, or pitch, but they cannot be catchers, third basemen, shortstops, or second basemen. The Giants finally solved this situation by trading Cepeda to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1966 for left-handed pitcher Ray Sadecki, a trade that worked out much better for the Cardinals than the Giants. McCovey, already a great power hitter, would dominate the league over the next five years after Cepeda’s departure, winning the MVP Award in 1969.

When McCovey arrived in San Francisco in 1959, Willie Mays, arguably the greatest, most charismatic player in the game, was 28 years old, an MLB veteran of seven years, yet new to San Francisco, as the team had only moved to the West Coast at the end of the 1957 season. This made Mays also something of a New York transplant. San Francisco always saw McCovey as truly its own, since he emerged as a star once the team had moved. Mays, like McCovey, had also been Rookie of the Year (1951). The men would play together on the Giants until 1972, when Mays, at the age of 41 and completely shot as a player, was traded to the New York Mets, mostly to end his career where it had started. Through 1966, Mays remained an extraordinary player, overshadowing McCovey, as he did virtually everyone else on a team that included at various times such distinguished players as Jim Ray Hart, the triple-threat brothers Felipe, Jesus, and Matty Alou, Bobby Bonds, and the stunningly brilliant showman pitcher Juan Marichal. Mays won the MVP Award in 1965 at age 34, leading the National League with 52 home runs and a 1.043 OPS. From 1957 through 1966, Mays finished somewhere in the top six of MVP voting. Mays had the glow of glory about him that not only made him seem so alive but made watching him so inspiring.

But Mays began winding down dramatically after age 35, and McCovey became the primary hitting star of the team. It did not seem to bother McCovey to have been in Mays’s shadow. The two men got along fairly well. They even roomed together a few times on road trips. (68) “‘I knew Willie before I came up to the Majors,’ McCovey said, ‘A lot of people don’t know, but I stayed at Willie’s place in New York when I was just a teenager…’ McCovey appreciated the hospitality and admitted feeling in awe of his host.” (72) They were both immaculate dressers, even insisting that their baseball uniforms be tailored to fit them well. In this way, they resembled Black musical performers like Duke Ellington and Miles Davis and players from the old Negro Leagues like Satchel Paige and Oscar Charleston, who felt that being well-dressed was a requirement of being a professional. It was what their Black public expected of them. Incidentally, McCovey was a big jazz fan and music talent scout in his free time. (157) Many players worked jobs during the offseason, a different era than now, when ballplayers have rigorous training schedules during the winter and make enough money to not have to work when they are not playing. “‘Mays was Mays,’” McCovey said, ‘Nobody was as good as Mays. He was amazing. He didn’t do anything during the offseason. Then, on the first day of spring training, you would think it was midseason, the way he went out there and played. Everybody else was huffing and puffing, trying to get in shape.’” (75) Yet one cannot help but think that McCovey was proud, even relieved, when he became, as he put it, “‘the number-one San Francisco Giant.’” (67) McCovey would hit more than 30 home runs seven times in his career. He would lead the league in home runs three times, twice in runs batted in. When he was good, he was very good. He was not Mays, but as he said, nobody was.

A Giant Among Giants is not a “life and times” biography. It does not situate McCovey in the social and historical contexts of America beyond baseball: the civil rights movement, Black Power, the Vietnam War, illegal drug use, the sex revolution, women’s rights, disco music, the rise of free agency, Watergate, Blaxploitation films, or the rise of the National Football League and its impact on major league baseball. McCovey was essentially a cold war era ballplayer, but during that portion of the cold war where America’s hubris had cost it some of its prestige, and where a vibrant, rising leftwing was beginning to have an impact on the culture, but where conservatives were making themselves anew by denouncing the failures of the welfare state among a lower middle class that was more inclined to listen than before. A writer who wants to do the “definitive” biography of McCovey is hardly foreclosed by this book.

It did not seem to bother McCovey to have been in Mays’s shadow. The two men got along fairly well.

A Giant Among Giants is mostly stories and quotes from various ballplayers of McCovey’s era (1959-1980), speaking well of him, of course, but also providing a vivid portrait of the man as a ballplayer. The author is to be commended for the number of interviews he conducted. There are striking tidbits in the book: for instance, McCovey was a strong supporter of Barry Bonds being inducted into the Hall of Fame and was intensely angry when his good friend and fellow Hall of Famer Joe Morgan wrote a letter to the Baseball Writers’ Association of America in November 2017 urging them not to vote for any players who admitted using steroids, failed drug tests, or were mentioned in the 2007 Mitchell Report. (169). Bobby Bonds, Barry’s father and a vastly gifted player afflicted by alcoholism, played with the San Francisco Giants in the late 1960s and early 1970s, his time overlapping with McCovey’s latter years with the team. McCovey had known Barry from childhood and this surely affected his view of the situation. Another tidbit is McCovey’s very outspoken racial view about why the National League so completely dominated the American League in All-Star Games, winning 25 of 29 from 1960 to 1985. “‘The only good team in the American League was the Yankees, and at one time you had to be lily-white to play with them. It was a big breakthrough when they brought up Elston Howard. So all your great black superstars went to the National League, with the Giants and with Brooklyn,’ McCovey said. ‘I think the National League was superior. That superior.’” (171) This observation about the All-Star game is more valid for the 1960s than the 1970s. Take the 1975 All-Star Game: the National League’s starting lineup included three Black players and one Hispanic (Joe Morgan, Dave Concepción, Lou Brock, and Jimmy Wynn). The American League’s starting lineup included two Black players and two Hispanics (Rod Carew, Bert Campaneris, Reggie Jackson, and Bobby Bonds). The American League had one Black pitcher on its staff (Vida Blue) and the National League had none. The National League had seven Black and Hispanic reserve players (Manny Sanguillén, Tony Pérez, Bob Watson, Dave Cash, Bill Madlock, Al Oliver, and Reggie Smith); the American League had six (George Scott, Jorge Orta, Hank Aaron, George Hendrick, Hal McRae, and Claudell Washington). There was little racial difference between the two teams. The National League won that particular year, 6-3.

McCovey would hit over 30 home runs seven times in his career. He would lead the league in home runs three times, twice in runs batted in. When he was good, he was very good. He was not Mays, but as he said, nobody was.

McCovey died on October 31, 2018, at the age of 80, from a list of ailments. He had endured many surgeries both during and after his career. He played in a great deal of pain for most of his career, which was heroic. He was in a wheelchair for the last several years of his life and suffered from infections caused by his knee replacements. Doctors wanted to amputate both his legs, but he refused. “‘He wanted to be a whole person,’” his daughter said. (164)

For those who can remember from their childhood watching Willie McCovey play (as I do, still remembering the screaming line drive he hit right at Yankee second baseman Bobby Richardson that ended the 1962 World Series, “one of the hardest balls I ever hit,” he said, jokingly asking Richardson years later did his hand still hurt from catching it), A Giant Among Giants is a fine book, not the thick description bio that someone will write one day, but steeped with a rich sentimentality about an era long gone, written by someone who truly loves his subject, a bio about a subject who deserves to be a beloved athlete.