How Zelensky Might Channel Thucydides

By Ben Fulton

March 14, 2025

Every political moment has its tropes. Our current political moment has at least two.

The first, used to describe any dizzying scale of change across time, stems from a reminder by Mexican poet Homero Aridjis ) though it is commonly attributed to a paraphrase by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin): “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” Like a valley of mushrooms after a big rain, this phrase has sprouted seemingly everywhere since the second Trump administration, most notably here, here, and here. Dozens more examples are sure to arise in the future, so durable is this phrase.

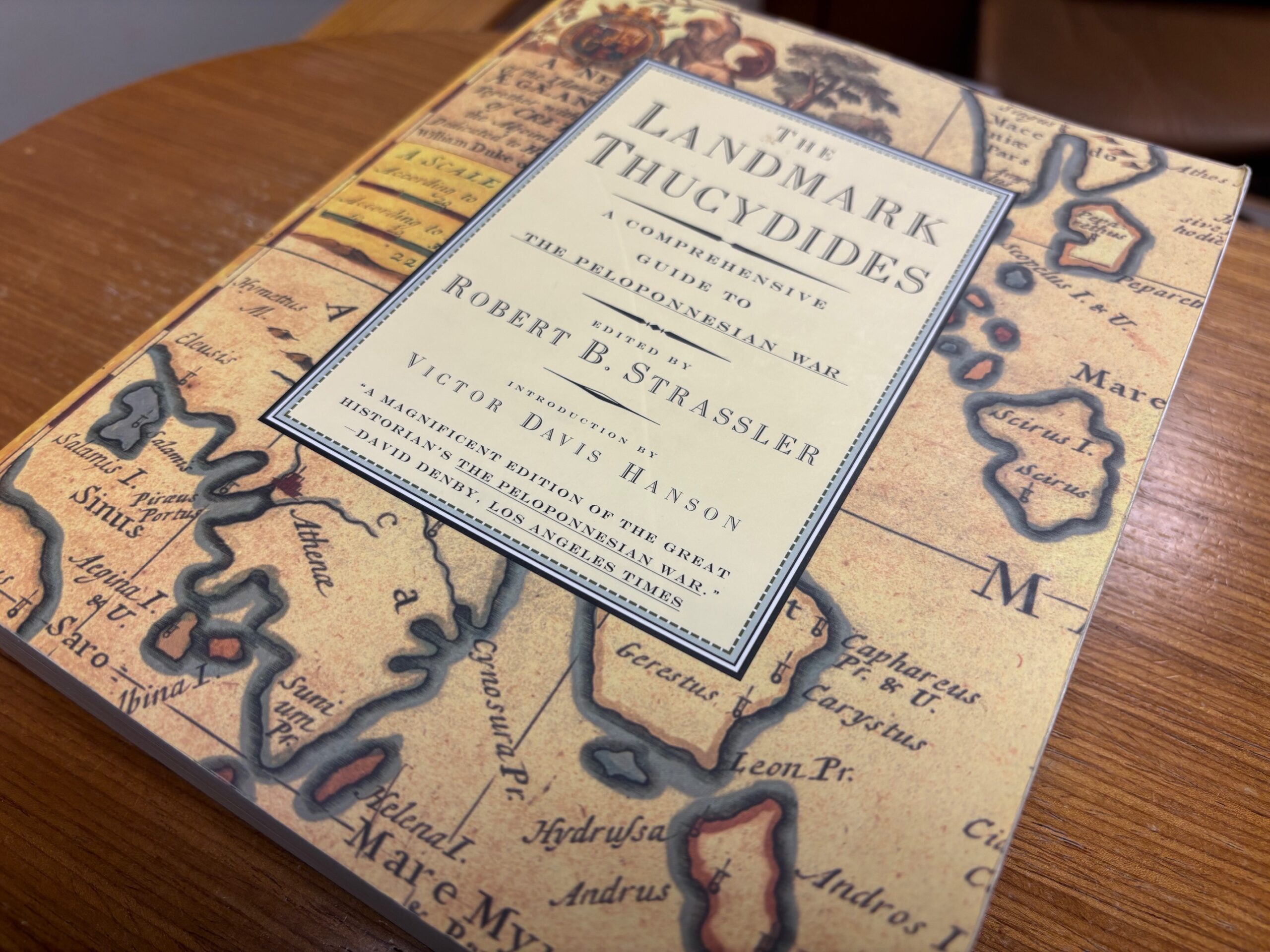

The second trope is far more reliably sourced, originating from that knotty tome of ancient Greek history, Thucydides’s The History of the Peloponnesian War (470/460 BCE): “The strong do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must.” (Some translations substitute “can” for “will,” but the phrase retains its unyielding flintiness either way.) This too, has sprouted everywhere, but with more resiny outrage than the first phrase. We can find it here, here, here, and here. Onward it marches as the second Trump administration enacts its helter skelter proclamations in service of “the president’s agenda.”

Thucydides’s analytic account of the thirty-year conflict between maritime, artistic, democratic (loosely defined, as women and slaves could not vote) Athens and militaristic Sparta is the magisterial font of not just every historian, ancient or modern, but also U.S. State Department insiders and anyone who fancies themselves specialists in international relations. Thucydides has been dubbed the first “scientific” author of history, and The History of the Peloponnesian War has been the go-to guide for hard lessons of antiquity ever since it was first read. Unlike other history books consigned to the dustbin of irrelevance, even if widely read for their prose style, e.g. Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, The History of the Peloponnesian War’s reputation remains fierce and durable. No less than Thomas Hobbes translated it into English, so persuaded was he by Thucydides’s realist utility. Not so long ago, even figures of popular scholarly culture advocated that everyday people read this all-important book. “He [Thucydides] cannot be read except with one’s full attention and is one of those writers who yield more with each rereading,” writes Clifton Fadiman in his 1960 book The Lifetime Reading Plan. “Finally, he is the first historian to grasp the inner life of power politics. Hobbes, Machiavelli, and Marx are, each in a different way, his sons.”

During the turmoil and tragedy of the Vietnam War, Thucydides’s account of Athens’s military campaign against Sicily was seen as an ancient warning against foreign wars. In the run-up to the Iraq War of 2003, then “neo-con” scholars such as Victor Davis Hanson employed Thucydides as a primer on the necessity of pre-emptive war, even if in a foreign country, to combat international Islamist terrorism. During the pandemic, Thucydides was invoked as a reminder of unseen ways public health disasters upended public trust and destroyed the virtue of long-range planning crucial to civilization’s foundation.

“The strong do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must” is the detonating line from Thucydides’s famous Melian Dialogue, an extended conversation between two parties, the Athenians and the Melians, about what constitutes “fair treatment” between victors and the vanquished or, in the case of this dialogue, between the powerful in search of more power and a far less powerful neutral party.

Throughout his account of the war, Thucydides seemingly gives the Athenians the benefit of the doubt. (He was one of them, after all. And his rendering of Pericles’s funeral oration portrays Athens as magnanimous and honorable even if they, like most people, dislike war.) The realist truth-teller in him, however, does not spare the brutal picture of his own loyalty to Athenians. After an extended negotiation in which the Melians, who hoped to remain neutral in the war between Athens and Sparta, argue that slaughtering the conquered will create more enemies for Athens, rather than helpful future allies thankful for mercy shown, and that the moral imperative of civilized treatment must be respected, the Athenians resort to the more simple argument that power is the only imperative worth discussing. After a few light skirmishes on the island, the Melians surrender, the men are executed, and the women and children are enslaved.

The dialogue and ensuing slaughter have served as an example ever since of how a once noble civilization slides so easily into barbarity. For some historians, it even stands as a prelude and analog of Germany’s slide from scientific and artistic paragon—the nation of Bach, Goethe, and Leibniz—into fascistic, racist blood-lust. Power corrupts. Power tempts. It matters not one whit how sophisticated and civilized you believe your country is.

The Melian Dialogue, read in full here, has become a favorite example of ancient game theory, as it documents the weight of outcomes given various options and predictions between parties. True, good-faith negotiation can only occur between equal powers in an environment in which skills of rhetoric and persuasion must be left to prevail, hopefully with both sides happy with the outcome. The sad fact of our current political times is that this equality is elusive against an all-demanding, all-consuming “agenda.”

Thucydides’s lingering message, however, is that history preserves the moral imperative, if not necessity, of treating the powerless ethically, if not even mercifully. Immediately after the Athenians invoke their now famous phrase of power and expediency, the Melians waste no time reminding them that, sooner or later, moral arguments benefit everyone:

… you should not destroy what is our common protection, namely the privilege of being allowed in danger to invoke what is fair and right, and even to profit by arguments not strictly valid if they can be persuasive. And you are as much interested in this as any, as your fall would be a signal for the heaviest vengeance and an example for the world to meditate upon. (Book V, Section 90; Richard Crawley, trans.)

Do not be so sure, the Melians tell the Athenians, that threats and hostility will turn neutral players or even enemies into docile subjects. Be more certain that threats and hostility will turn them instead into angry, vengeful people. The rules of war may laugh at mercy and justice, but war cannot last forever, else people grow exhausted and demand justice’s return. It is a lesson dramatized in Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy some twenty years later, in 458 BCE. And it is a lesson Thucydides drove home even before the Melian dialogue, earlier in his account of the war, in the argument between Cleon and Diodotus about sparing the Mytilenians in Book III, Sections 47-49, and in his famous description of the evils of revolution in Book III, Section 84:

… men too often take upon themselves in the prosecution of their revenge to set the example of doing away with those general laws to which all alike can look for salvation in adversity, instead of allowing them to subsist against the day of danger when their aid may be required. (Richard Crawley, trans.)

Justice is the first casualty when power is the only currency that matters. Our “common protection,” or “the privilege of being allowed in danger to invoke what is fair and right,” are being sorely tested. So too, “those general laws to which all alike can look for salvation.”

In our current political environment, it is not only justice that is being questioned, but the value of alliances as well. There is no suitable analog between Athenians/Melians and Ukraine/United States, but certainly the question of aiding a besieged nation faced against an aggressor is one Thucydides would never have shirked from analyzing. One of the more important lessons of The History of the Peloponnesian War is that the balance of power between nations and parties always seems fixed and unmovable, until suddenly they become unmoored, rearranged, or role-reversed. All decent people hope that justice and mercy will return in the aftermath of conflict, but until that happens there may be nothing to save us from the ravages of conflict. As everyone who has read Thucydides knows, Athens, which held itself in such high esteem but failed to unite all of Greece before going into war, lost to Sparta, which in turn managed only to eke out a marginal victory in which everyone across ancient Greece and the Peloponnesian islands lost.

We can be certain that President Trump, a creature of naked transaction, has never bothered to read ancient Greek history. It is anyone’s guess as to whether Ukrainian President Volodoymyr Zelensky has done so, even if his words spill into realms that Thucydides, with his imperatives for the preservation of law and solidarity against violence and calamity, would recognize at once.

Sitting in the now infamous Oval Office meeting with President Trump and Vice President JD Vance on Feb. 28, and confronted with questions about his attire and fealty, Zelensky did his best to advance the conversation. The lessons of history are there for us to decipher and benefit from, he said in effect, or ignore at our peril.

“You have a nice ocean and don’t feel [it] now,” Zelensky said, “but you will feel it in the future.”