From Luke Skywalker to Moses

The many realms of the second chance

November 22, 2025

“I say, follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be.”

—Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth with Bill Moyers (Doubleday), p. 20

The Second Chance.

A simple term expressing a simple concept, right?

Wrong.

To echo Walt Whitman—who found his “second chance” through poetry—the term contains multitudes, ranging from the mundane to the mythic, from the everyday to the epic. And on a deeper level, the term contains a profound life challenge for you and for me—profound, that is, so long as we avoid what has come to be known as the Flitcraft Parable. So join me now on a journey that spans from the Vegas craps table, prison, Luke Skywalker, Moses, and finally to us.

We start at the most commonplace meaning of the term. For us lawyers, a second chance is what we seek when our client receives an adverse decision at trial—namely, an appeal to the higher court, which is our client’s second chance to get a better result. For the gambler at the craps table in Vegas, the “second chance” refers to the opportunity to place what is known as a “come bet” after the initial roll, giving the gambler another chance to win on that next roll. For the ambitious high school senior, it is taking the SATs for a second time in the hopes of improving the score. For the baseball reliever, it is what he seeks when stepping onto the mound with a one-run lead in the bottom of the ninth inning after having blown his save opportunity in the previous game. And for a baseball fan, nothing captures the near religious belief in the promise of a second chance better than that age-old mantra of Chicago Cubs fans. It is always voiced in the aftermath of yet another disappointing season, year after year after year for more than a century: “Wait ‘til next year.” And finally, that wait came to a glorious end in 2016, when the Cubs defeated the Cleveland Indians to capture their first World Series championship since 1908, and their first ever while playing at Wrigley Field.

Moving to a deeper meaning of “second chance,” we begin at your state’s penitentiary. The term comes from the Latin paenitentia, which means “penitence”—and thus a penitentiary (at least as originally conceived) is a place where the justice system sends a convict to make penitence for the crime committed. And when that penitentiary term is completed and the prisoner is released—typically, on parole, which comes from the Old French phrase parole d’honneur (“word of honor”)—he or she has a “second chance” in life. While not all former prisoners take advantage of that second chance, some who do have been the subject of stirring tales of redemption. Indeed, while I was mulling over this version of the second chance, the ABA Journal published an article entitled “From behind bars to passing the bar,” an inspirational account of three lawyers, all having grown up in poverty and all having started their second career paths in prison. Two had been incarcerated for selling drugs, the third for a carjacking, and now all are successful attorneys.1 The appeal of these “second chance” prisoner tales has inspired both authors and Hollywood, whose redemption movies include one of my favorites, The Shawshank Redemption (1994), which is the cinematic adaptation of the Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption. (1982)2

While not all former prisoners take advantage of that second chance, some who do have been the subject of stirring tales of redemption.

Hollywood has embraced the concept of the second chance, creating scores of such movies with happy endings, beginning with, of course, Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Other heartwarming, transformative “second chance” motion pictures include The Lion King (1994), The Wizard of Oz(1939), Good Will Hunting (1997), Legally Blonde (2001), Hoosiers (1986), The Bad News Bears (1976), Rocky (1976), and probably many more on your list of favorites. My “second chance” list includes Field of Dreams (1989, where an Iowa farmer obeys a mysterious voice telling him to build a baseball field on his land, and that field magically transforms his life); Groundhog Day (1993, where a narcissistic weatherman finds himself in a “second chance” time loop on Groundhog Day and is transformed from nasty selfishness to joyful selflessness), and Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941, where John Sullivan, a director of popular Hollywood comedies, has become jaded with his happy-sappy films and decides to travel the country as a tramp to understand and make a film about the “real Americans”).3

A related realm of upbeat “second chance” tales can be found in what has come to be known as the Great American Songbook, a few of which have been sung in 1966 by Frank Sinatra, including “That’s Life” (composed by Dean Kay and Kelly Gordon in 1963). The song opens with Sinatra responding to onlookers who have witnessed his big failure, namely, that he had been “riding high in April, shot down in May.” They shrugged and told him “that’s life,” i.e., hey, it happens, dude. His response:

But I know I’m gonna change that tune

When I’m back on top, back on top in June

And he ends the song with a defiant “second chance” pledge that he’ll “pick myself up and get back in the race.” In his 2009 inaugural address, President Barack Obama paraphrased the lyrics from the famous 1936 Jerome Kern/Dorothy Fields song about second chances, “Pick Yourself Up,” “Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin the work of remaking America.” The original lines are “Pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and start all over again.”

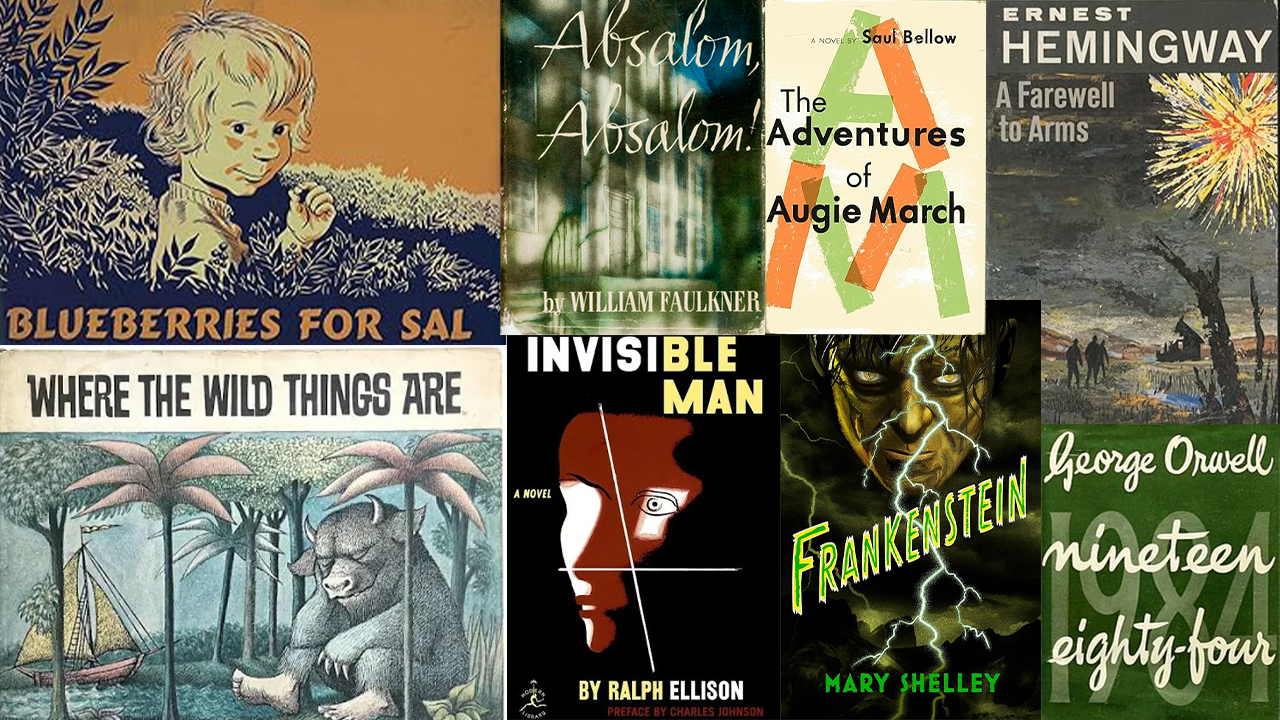

So, too, the “second chance” theme has inspired some of our greatest works of literature, where the protagonist makes a major life decision that takes him or her in a new direction. But here, unlike Hollywood, the works of literature are not all upbeat. Instead, they fall into two disparate genres: tragedies and, for lack of a better term, romances.

As its genre name suggests, a tragedy presents a grim view of the false promise of a “second chance.” Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878) is a warning against viewing passion as a form of redemption. The title character, trapped in a loveless marriage, seizes on her version of a second chance—a daring adulterous love affair—but all goes horribly wrong, ending with her suicide beneath an oncoming train. Hemingway’s A Farwell to Arms (1929) ends on a similarly bleak note: Frederick Henry, an American lieutenant working with the Italian ambulance service in World War I, is injured and falls in love with Catherine Barkley, the hospital nurse who tends to his wounds. He returns to the front, but a botched retreat inspires his “second chance” epiphany: he deserts the army to reunite with the now pregnant Catherine in Switzerland. But the novel ends with her death in childbirth after their son is stillborn, and in the closing scene of the novel, Frederick leaves the hospital, walking alone in the rain.

Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1878) is a warning against viewing passion as a form of redemption. The title character, trapped in a loveless marriage, seizes on her version of a second chance—a daring adulterous love affair—but all goes horribly wrong, ending with her suicide beneath an oncoming train.

Others include Captain Ahab’s second chance at revenge against Moby Dick, the sperm whale that bit off his leg, in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel. Ahab’s monomaniac quest ends with his gruesome death when, as the harpooned whale darts forward, the rapidly unspooling harpoon line catches around Ahab’s neck, shooting him out of the boat as Moby Dick dives underwater, dragging Ahab down with him. So, too, the death of the protagonist concludes each of Shakespeare’s great tragedies, most of them tales of a grasp at a second chance gone horribly wrong—from Macbeth (1623) to Antony and Cleopatra (1607) to Romeo and Juliet (1597). Add to that list a gloomy pair by Joseph Conrad: Lord Jim (1900) and Heart of Darkness (1899), two seemingly remarkable “second chance” moments in the lives of Jim and Kurtz that nevertheless end in their deaths. The quintessential American novel of the second chance gone wrong—The Great Gatsby (1925)—ends with the murder of the former North Dakota farm boy named James Gatz, who had reinvented himself as the glamorous Jay Gatsby. The novel concludes with our disillusioned narrator’s somber thoughts about the death of both Gatsby and the iconic second chance known as the American Dream:

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. … and one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne ceaselessly into the past.

But literature—both classic and contemporary—has also given us plenty of upbeat “second chance” novels, beginning with the works of Jane Austen, not only one of the English language’s greatest authors but the unquestioned master of the “second chance” romance novel. Other upbeat classics include William Shakespeare’s As You Like It (1623), Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847), and Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. (1859)4 One set of popular nineteenth-century “second chance” American novels became collectively known by the name of their author, Horatio Alger Jr, whose heroes are generally young boys who, through hard work and honesty, ascend from impoverished circumstances to become respectable and successful. The bestseller lists of our own era abound with romance novels and other works of “second chance” happy endings.

Literature—both classic and contemporary—has also given us plenty of upbeat “second chance” novels, beginning with the works of Jane Austen, not only one of the English language’s greatest authors but the unquestioned master of the “second chance” romance novel.

In other words, those blockbuster Hollywood movies and upbeat bestsellers reflect the popular culture’s embrace of the optimistic “second chance” story. That embrace, I came to realize, is also evidenced by the widespread impact of another significant group of ‘second chance’ tales”: the comic book superheroes, whose roster includes Batman, Spiderman, Wonder Woman, Black Panther, and Captain America. And, of course, the archetypal American superhero of comic books (and television, motion pictures, video games, action figures, and other collectibles): born Kal-El on the planet Krypton, he is given a second chance when his parents send their baby to Earth before Krypton is destroyed. His rocket ship lands in the countryside near Smallville, Kansas, where he is adopted by a farmer couple Jonathan and Martha Kent, who name the baby Clark Kent.

And that was the moment I realized the far deeper significance of the cultural embrace of these comic book superheroes. There was, I discovered, something special about these “second chance” superheroes, something almost, well, mythical.

Enter Joseph Campbell.

Back in 1949, this once-obscure professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College published The Hero with a Thousand Faces, a book that would become highly influential for its identification of universal themes and archetypes in mythical storytelling across history and around the world. Based on his study of myths (both written and oral), including the foundation stories of the major religions, Campbell developed the concept of the “monomyth” to describe the hero’s journey. As he explains:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered, and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man. (Campbell, 1968, p. 30)

The hero’s adventure begins in the ordinary world, where he receives a call to adventure—the “second chance.” Although at first reluctant to answer the call, a triggering event ultimately compels him to act. From that point on, often with the help of a mentor, he will depart from the ordinary world and cross into a far different realm. There, he embarks on a dangerous road of challenges, being tested again and again, often assisted by allies, until eventually he encounters the greatest challenge of the journey. Upon rising to that challenge, he will attain a powerful reward, or what Campbell refers to as a “boon,” which he brings back to bestow on his people.

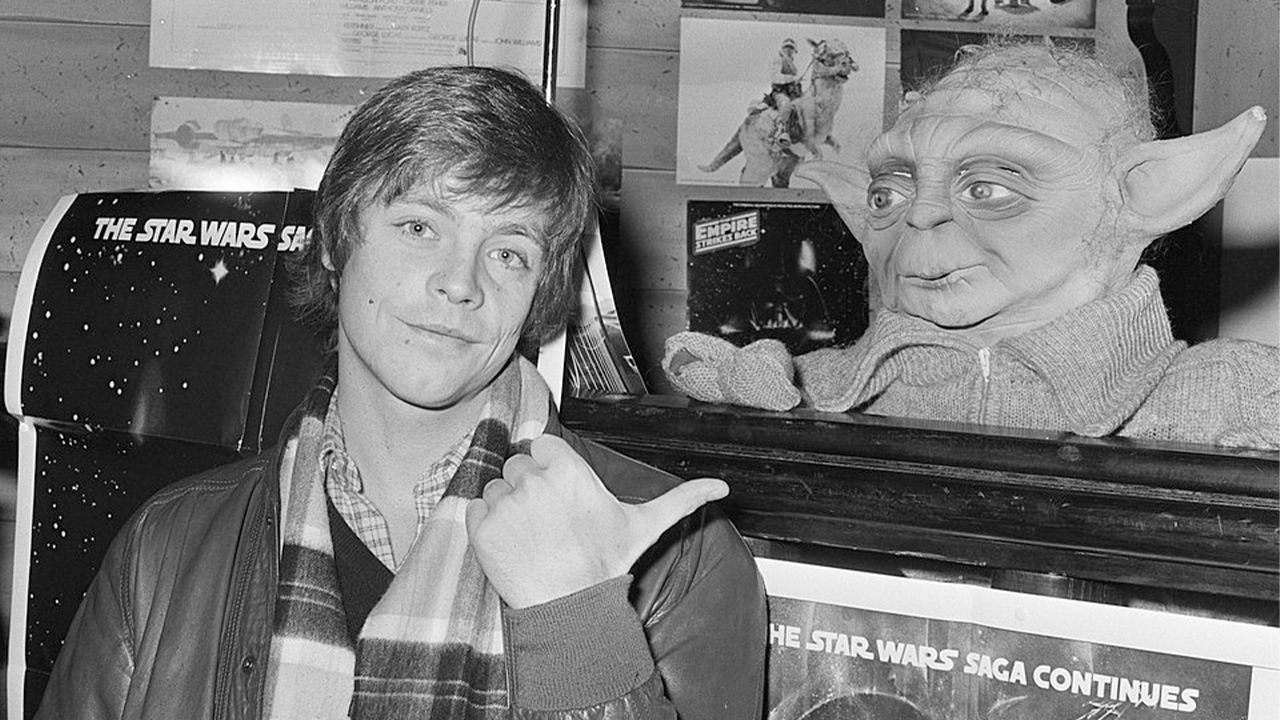

If this description reminds you a little of the story of Luke Skywalker in the Star Wars motion picture, it is no coincidence: George Lucas, the writer and director of the original film, was strongly influenced by Campbell’s book and later developed a close friendship with him. In his interview with Bill Moyers, Lucas described Campbell as his mentor in the creation of that movie.5

The story of Luke Skywalker follows Campbell’s structure of the monomyth. When we first meet Luke, he is an orphan raised by his uncle and aunt on a moisture farm on the desert planet Tatooine. After his uncle purchases two droids—C-3PO and R2-D2—Luke finds a message from Princess Leia inside R2-D2. When that droid goes missing, Luke heads out to search for it, where he is rescued from Tusken raiders by Obi-Wan Kenobi, an elderly hermit. R2-D2 then plays the message from Princess Leia in which she asks Obi-Wan to help her defeat the Galactic Empire and its Imperial stormtroopers. Although Obi-Wan tries to enlist Luke in the mission, Luke declines out of feelings of obligation to his family and the farm. But all of that changes when he returns to the farm to discover that the stormtroopers have murdered his uncle and aunt. And thus, with Obi-Wan as his mentor, Luke sets out on his “second chance” journey, and, per Campbell’s monomyth, gathers allies along the way (Han Solo and Chewbacca) on his perilous quest to defeat the Empire and save the Princess.

The monomyth of the hero’s journey, as Campbell explains, is the foundational story behind all the major religious figures around the globe, including Buddha, Jesus Christ, and Moses—who, like Luke Skywalker, was an orphan living in the countryside when he received a mysterious summons to a greater cause, although his came from a burning bush rather than a droid’s video. Initially reluctant, but finally, accompanied by his first ally, his brother Aaron, Moses sets off on his journey of perilous challenges, including his confrontations with Pharoah, the Ten Plagues, the crossing of the Red Sea, and forty grueling years in the desert. Along that path he gathered other allies, including Joshua, the Torah’s version of Han Solo. Campbell viewed Moses’ ascent to Mount Sinai, where he met with God and returned to his people with the Ten Commandments, as the classic example of the hero’s delivery of the boon to his people.

Okay, but by now you must be thinking, How is this relevant to my life? I am not some nerdy Peter Parker waiting for a bite from a radioactive spider to be transformed into Spider-Man. And yes, that tale of Prometheus stealing fire from the gods and bringing it back to mankind is totally cool, but it is pure myth and, anyway, last week at CVS I bought myself a Bic lighter.

Understood. But the real world is filled with transformative “second chance” stories—true tales of people who at some point in their lives answer the summons of a new path. Sometimes that transformation is epic, as exemplified not just by those former prisoners who became attorneys but by the famous “second chance” leap that Henry David Thoreau took in the middle of his life. He left his job at his family’s pencil factory in Concord to live in an isolated log cabin in the woods near a large pond that became the title of his book. As he explains in Walden:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.

Now I concede that we have other options—far less extreme than the “second chance” route that Thoreau took. Maybe your “second chance” dream is to learn to play the piano or to speak French or to become a gardener or a knitter, or a pickleballer. Which are all good. Regardless of your “second chance” goal, we need to heed the message at the end of the first sentence of that Thoreau quote: “not, when I came to die, to discover that I had not lived.” Which is similar to the advice my dad gave me decades ago. “Son,” he said, “in this lifetime, try to make your errors of commission, not omission. I know it can seem scary, but remember: if you take that leap and you crash, no big deal. You just get up, dust yourself off, and move on. But if you pass up that opportunity, it will haunt you for the rest of your life.” That was true even for Thoreau. If his move to the woods had fallen short of his expectations, he could always go back to the pencil factory.

Leaving aside the grand scope of the monomyth, it remains true that opportunities will arise along each of your life paths—forks in the road, both big and small, for us to consider. That defining moment of “second chance” was most famously captured by Robert Frost in his poem “The Road Not Taken,” which opens:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And, as the narrator struggles to decide which road to take, the poem closes:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

While scholars continue to argue over that poem’s message 6, I prefer to heed the advice of that renowned guru Yogi Berra: “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

And it is okay to think small. Baby steps, one after another, and you will get there. For example, when I decided to try to write a novel, I was a full-time trial lawyer and the father of five children. So obviously I could not do the modern equivalent of Walden and head off to the woods for a few years (with, I hoped, an electric outlet for my laptop). But as I mulled it over, I realized I could probably find enough time each night after the kids were in bed to write a page. Just a page. No big deal. Not a major time suck. Thirty or forty minutes at most. Do the math: a page a day adds up to 365 pages a year, which is enough for a novel. So, too, friends of mine—both former attorneys—retired to pursue their passions: photography for one, quilting for the other.

Maybe your “second chance” dream is to learn to play the piano or to speak French or to become a gardener or a knitter, or a pickleballer. Which are all good.

Then again, maybe your “second chance” dream is much bigger. Want to become a stand-up comedian? There are plenty of footsteps out there to follow, including those of Bob Newhart, who started as an accountant, Rodney Dangerfield, who started as a salesman, and Larry David, who started as a limousine driver. I have a friend, a passionate environmentalist, who exited his career as a successful lawyer and now runs an ecolodge in Costa Rica while serving as the co-founder and president of a regenerative agriculture organization.

I realize that some of you may scoff at the baby-steps version of a “second chance.” Pickleball as my life’s aim? Get real, Kahn! Understood. But if your “second chance” goal is a truly transformative one—a twenty-first-century version of Thoreau on Walden Pond—then before you take that bold leap into the unknown, please ponder the lesson of what is known as the Flitcraft Parable.

The origin of that parable dates back nearly a century to Dashiell Hammett’s detective novel The Maltese Falcon (1930). The tale of Mr. Flitcraft pops up, seemingly out of the blue, in Chapter 7 of the novel. At that point, the private detective Sam Spade sits down in his office across from Brigid O’Shaughnessy, the mysterious woman who has hired him, as he eventually learns, to find the priceless black statuette of the novel’s title. With no preamble, Spade begins to tell her about something that happened several years ago. It is the true story, he explains, of a man named Flitcraft, a successful real-estate agent with a happy family life and plenty of money in the bank. He left his office in Tacoma, Washington, one day, presumably to go to lunch, and disappeared. There had been no indication that he had been planning to leave and no evidence to justify a suspicion of secret vices or another woman in his life.

“He went like that,” Spade says, “like a fist when you open your hand.”

Five years later, Mrs. Flitcraft came to his office to tell Spade that somebody had seen a man three hundred miles away in Spokane who looked a lot like her husband. Spade tracked him down in Spokane, and they talked. Back on the day he disappeared, Flitcraft explained, he had been walking to lunch and passed by an office building under construction. At that very moment, a huge steel beam fell down from eight or ten stories above and smashed into the sidewalk, barely missing him, although a chip off the sidewalk did hit his cheek and left a scar.

But if your “second chance” goal is a truly transformative one—a twenty-first-century version of Thoreau on Walden Pond—then before you take that bold leap into the unknown, please ponder the lesson of what is known as the Flitcraft Parable.

Though he was, in Spade’s words, “scared swift,” he “was more shocked than frightened. He felt like somebody had taken the lid off life and let him look at the works.” The life he had known before going to lunch was “a clean orderly sane responsible affair” in which good people were rewarded with happy families and country club memberships. Now a falling beam had shown him that even good men lived “only while blind chance spared them.”

Instead of returning to his office, he just walked away, eventually returning to the Pacific Northwest to take a job in Spokane under the name Charles Pierce. And thus his grab at the “second chance.” But, as Spade learned, he had married a second wife who strongly resembled his first wife and was living a life nearly identical to the one he had left. As Spade explains, “I don’t think he even knew that he had settled back in the same groove he had jumped out of in Tacoma.” That, Spade concludes, was the part that he always liked: Flitcraft had “adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.”

The Flitcraft Parable has generated a raft of essays, from blog posts to scholarly articles, probing the meaning of that story, including the importance of defining your objective before taking that leap. To me, the central lesson of that parable—and one that each of us should keep in mind as we mull over a “second chance” opportunity—is best captured in these reassuring words of Thoreau:

I learned this, at least, by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.

1 “From behind bars to passing the bar,” ABA Journal (October 29, 2024): https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/from-behind-bars-to-passing-the-bar-these-lawyers-began-their-career-paths-in-prison

2 While the poster of Rita Hayworth (from the 1946 movie Gilda) is included in the motion picture version, the main poster in the movie, which covers the hole in the prison cell wall that leads to the escape tunnel, was of Racquel Welch (from the 1966 movie One Million Years B.C.).

3 The title of the aspirational film that Sullivan never makes—O Brother Where Art Thou—became the actual title of a wonderful satirical comedy-drama musical “second chance” film by two big fans of Preston Sturges, Joel and Ethan Coen.

4 But Dickens was no stranger to the bleak “second chance” novel. His oeuvre includes the appropriately named Bleak House, perhaps the grimmest depiction in all literature of the tragic folly of relying on a lawsuit as your second chance for redemption.

5 https://billmoyers.com/content/mythology-of-star-wars-george-lucas/. The conversations between Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers that were eventually edited into the six-part PBS series The Power of Myth were filmed, in large part, at George Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch.

6 See, e.g., Orr, David, “The Most Misread Poem in America,” The Paris Review (Sept 15, 2015) (https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/09/11/the-most-misread-poem-in-america/)