Cecil Brown is senior lecturer in urban studies at Stanford University where he is also a researcher at The Spatial History Project. He is author of the novel The Life and Loves of Mr. Jiveass Nigger, originally published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 1969.

By Cecil Brown

By

Cecil Brown

In 1976, James Baldwin showed up in Berkeley to visit me and we hung out and had a great time. Although he never mentioned Truman Capote, I am willing to bet that if I had asked him he would have said, “Yeah, I stopped off to see if you were here to see him on my way out of New York.” The fictional truth is a greater truth than any that we have in real life.

By

Cecil Brown

When the door of the Lincoln Town Car shut, I looked out of the corner of my eye and saw Sean coming towards me. I did not get up. He came and sit down right beside me, But I was already thinking and remembering and recalling how Daddy and Uncle Lofton would settle themselves before they worked on the rail tracks.

By

Cecil Brown

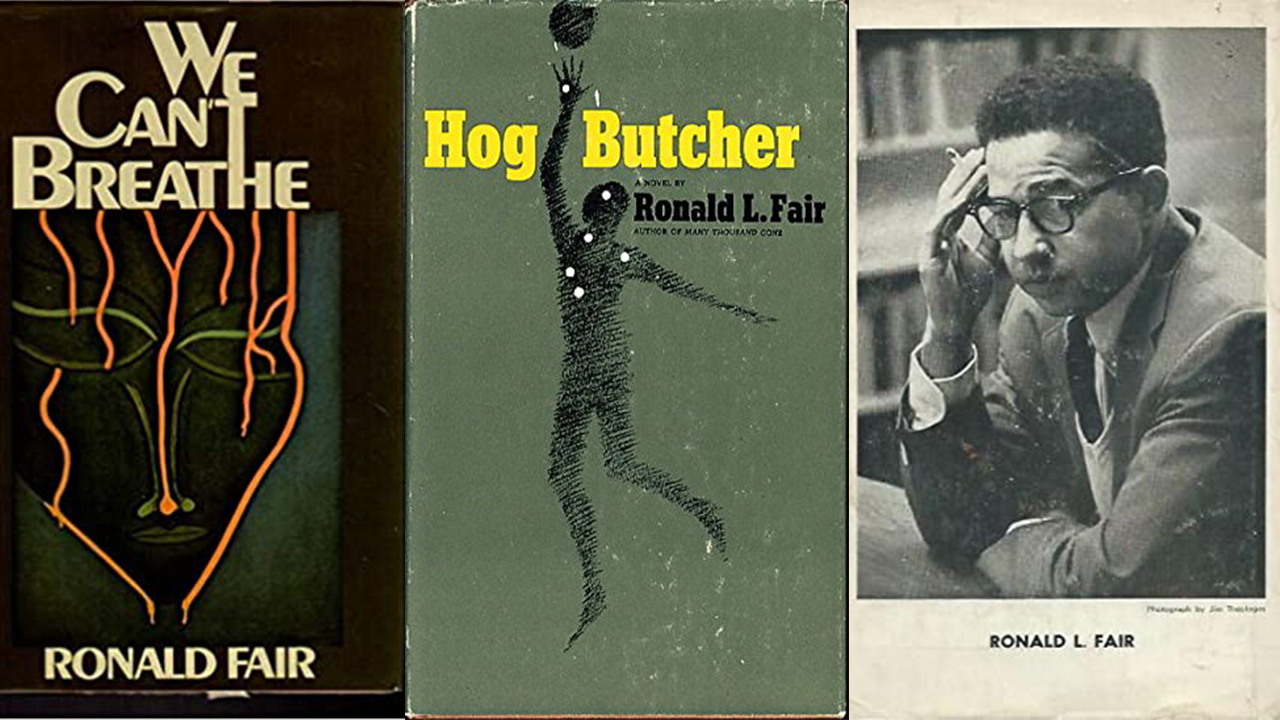

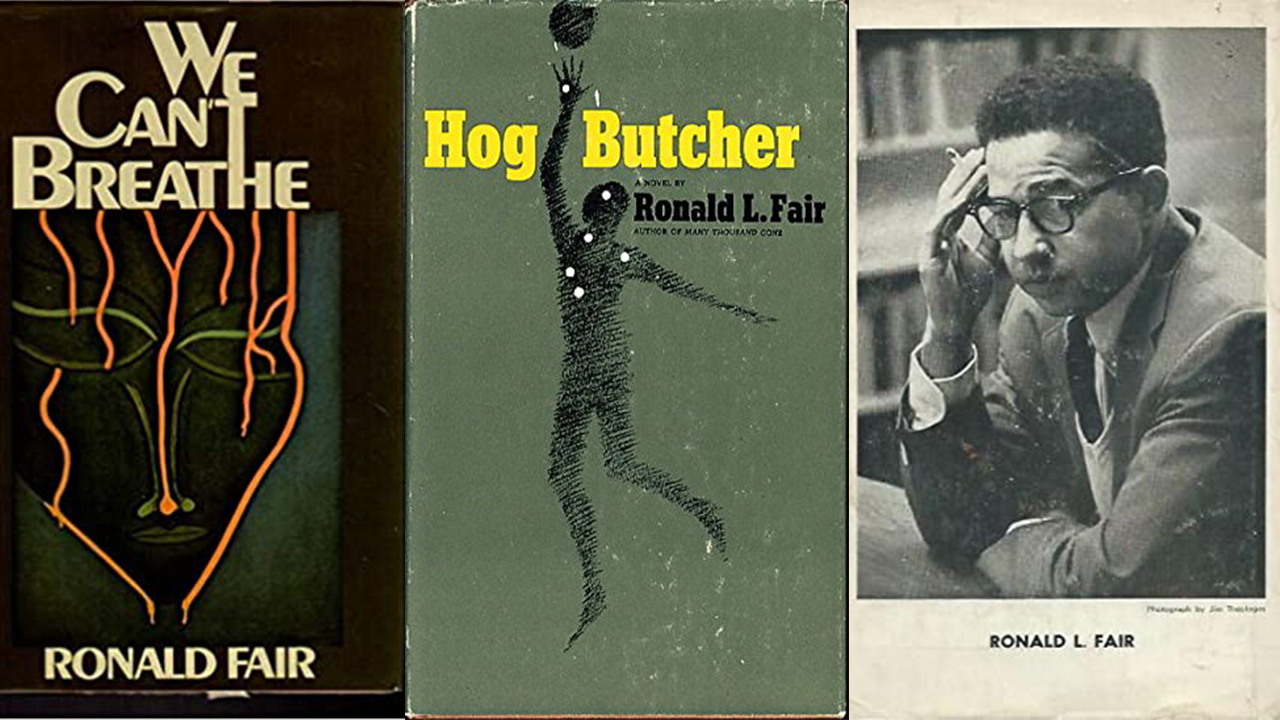

Nineteen seventy-two saw the publication of the autobiographical novel We Can’t Breathe. For several years, aided by several writing grants, Ronald Fair traveled abroad, pursuing a writing life of great ambition. In the early seventies critic Shane Stevens called him “one of the two best black writers in the country.” Yet this promise somehow never came to full fruition.

By

Cecil Brown

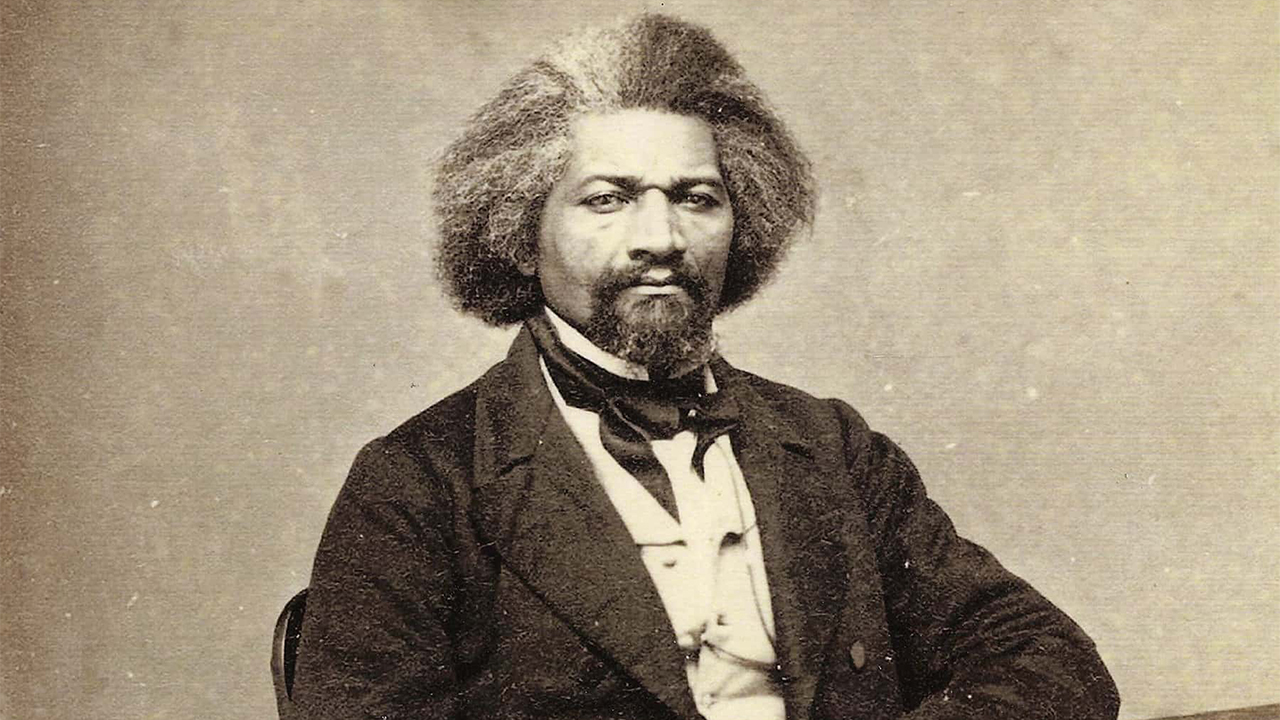

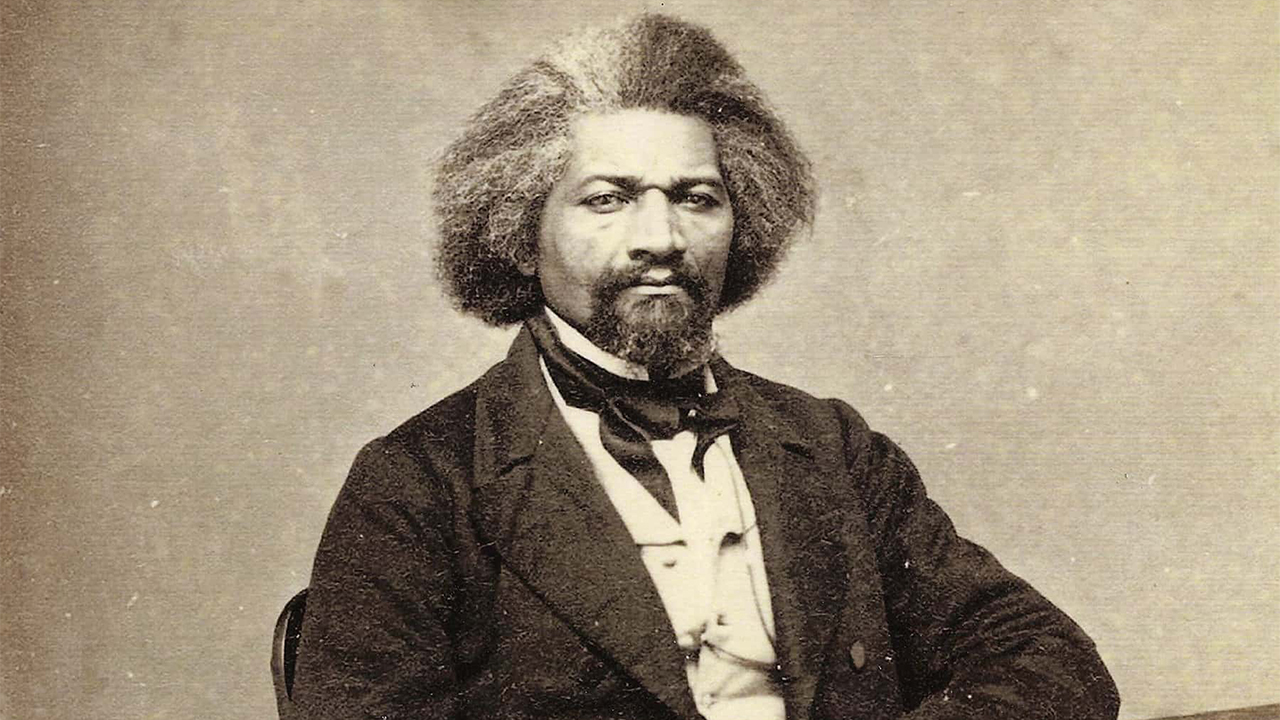

Frederick Douglass saw the Fourth as a mockery, because he was still a slave, but slave poet George Moses Horton saw Independence Day as one to be celebrated as a victory for all. As indeed it was.

By

Cecil Brown

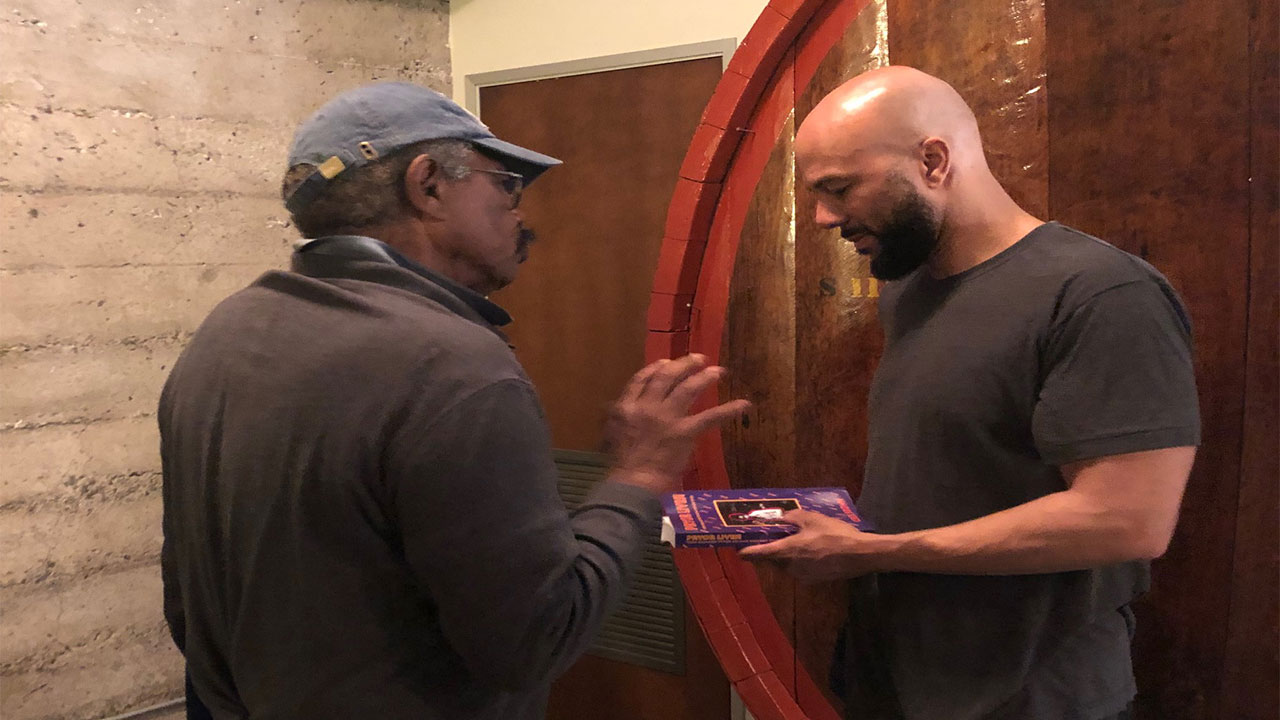

Who was George Moses Horton? I suspect that he was someone like Common, who would dance and gesture when he composed.

By

Cecil Brown

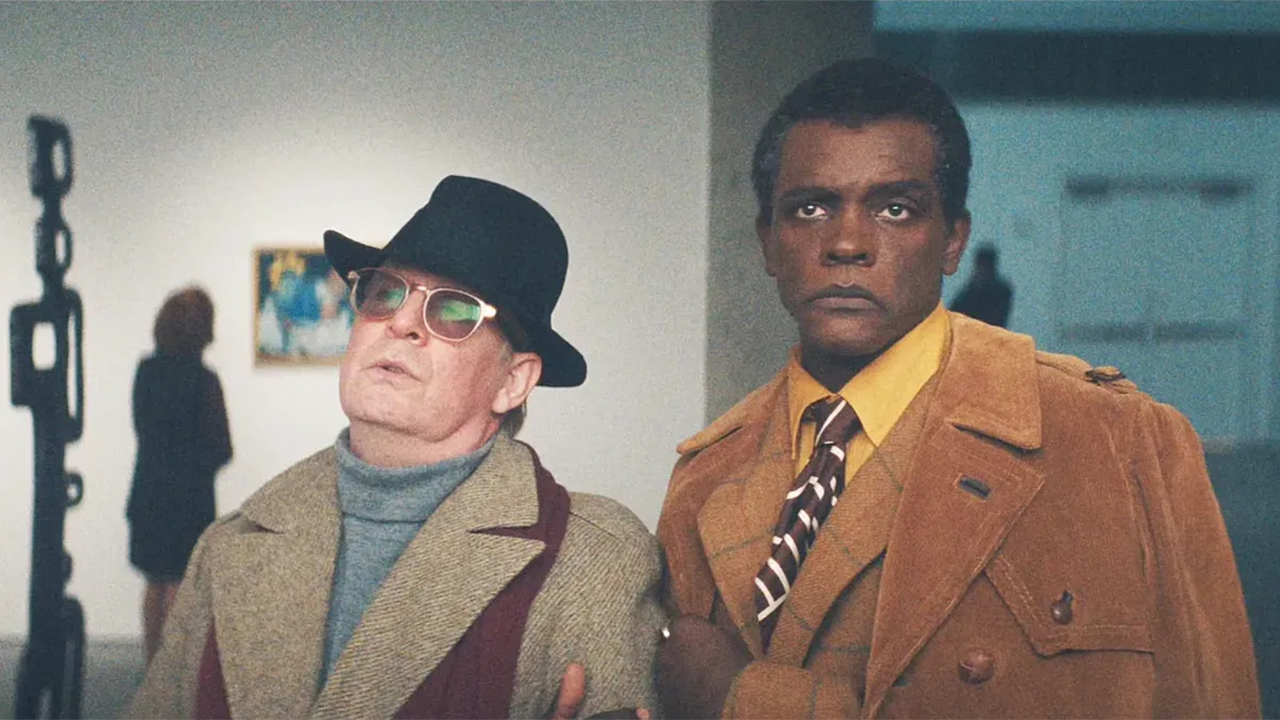

Apparently, Jimmy had been given an advance of $100,000 for If Beale Street Could Talk with the promise of another $200,000 on completion. I gathered that he was anxious to get it done. It seemed as if he needed the seclusion of this special place to write about the tragic life of black Americans.

By

Cecil Brown

The Common Reader remembers the iconic African-American novelist Toni Morrison in this 1995 interview: "Black writing has to carry that burden of other people’s desires, not artistic desires but social desires; it’s always perceived as working out somebody’s else’s agenda. No other literature has that weight."