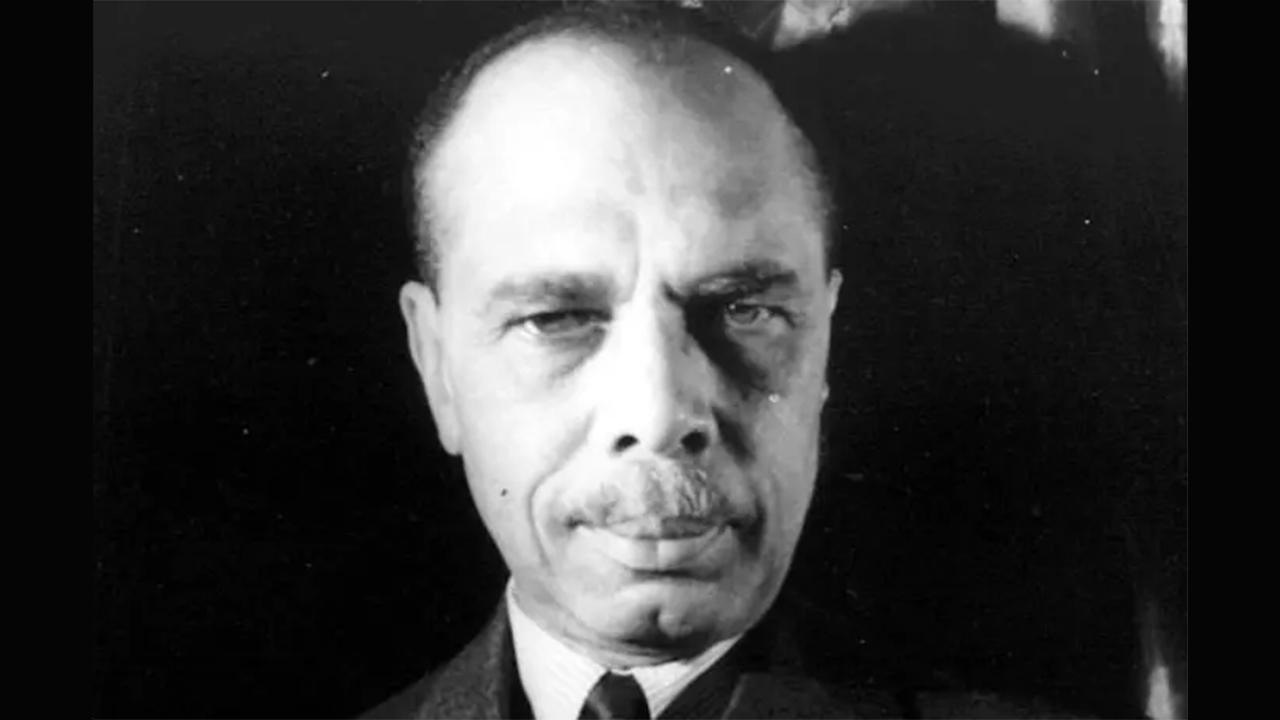

Editor’s preface: James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) was something of a Renaissance Man. A native of Florida, the same state that produced novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston and labor leader A. Philip Randolph, Johnson was a teacher, poet, novelist, civil rights leader, and songwriter. Among his most significant achievements are The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912, 1927), a novel that stands as one of the cornerstones of modern African American literature, God’s Trombones (1927), one of the more impressive examples of black dialect poetry, and The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), one of the landmark anthologies of black literature and one of the books that helped launch the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson, an astute political figure, was able to negotiate both the Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois factions. He was a friend to both men. He served as U.S. consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua, as well as field secretary to the NAACP in the 1920s. (He was fluent in Spanish.) But it is as a composer that he is probably best remembered today among African Americans. He, along with his brother, John Rosamund Johson, composed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” also called the Black National Anthem, in 1900. He worked a great deal in black musical theater in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and knew the major black performers and composers of the period, just as did Lester Walton (1882-1965), a leading African American music and theater critic and journalist of the day. This piece, from the New York Age, a black paper for which Johnson wrote regularly, displays Johnson’s knowledge of music and his wit about the unappreciated lyricist, which Johnson was himself.

My colleague, Lester A. Walton, expressed mild indignation last week over the manner in which lyricists are generally ignored on concert programs. Writing of a concert recently given in Boston, Mr. Walton said:

In glancing over the program I note that the usual policy of completely ignoring the lyricist was consistently followed out. For what reason the writer of the words to a song is always kept in the background on high-class music programs has always been a source of wonderment to me. When I ask those who should know, for instance the publisher, I am repeatedly told, “Merely a matter of custom!”

For every custom there is some sort of a reason. Then if it is the custom generally to ignore or not to accord recognition to the writer of the words to a musical composition on what reason is the custom founded?

To get at the reason we must go back a little into the history of words wedded to music. The first phase of what is known as the modern song was the songs of the troubadours. The troubadours flourished from the 10th to the 14th centuries. In these songs the words were the chief feature, the music was merely incidental. The poets told in these songs wonderful and beautiful stories of war and adventure and love, and the listeners hung upon each word that fell from the singer’s lips. With the development of the vocal art there came a change; the listener gradually became more interested in the sound than in the story. Early in the 18th century the concert aria was well established, and the music was filled with turns and trills and other florid decorations. People were astonished and then delighted by these vocal pyrotechnics. Words to a song took not only second, but very insignificant place. In fact, the greater portion of many of the songs required nothing more than they syllable “Ah.” As a natural consequence, the words fell off in quality.

The same thing was true in opera. The Italian school was then in undisputed ascendancy, and vocalization was carried to such a high pitch of perfection that libretto writers had to make their words fit the notes as best they could. As a result, the words to the opera of the period were often little more than doggerel. Sopranos simply tra-la-la-ed. That was opera.

… how many even of the people who are well versed in music know who wrote the words of “Aida”? The man who wrote the words of this immortal work was Antonio Ghislanzoni. Be honest and admit that you never heard of him.

But even with the change wrought in songwriting by Schumann and Brahms and in opera writing by Wagner, a chance which made it the business of the composer to interpret the words of the text and to emphasize the emotional situations of the story, words remained an unimportant part of musical compositions. Take what is, perhaps, Verdi’s greatest opera, “Aida,” an opera in which he followed the Wagnerian principle of making the music support and develop a tragic story; how many even of the people who are well versed in music know who wrote the words of “Aida”? The man who wrote the words of this immortal work was Antonio Ghislanzoni. Be honest and admit that you never heard of him.

But let us come down from opera. If a vote should be taken on the most famous song written in American in the last twenty years, I have no doubt that the vote should go to “The Rosary.” It is a beautiful song, a song that everybody knows, and stranger still, a song to which everybody knows the words. When people hum “The Rosary,” they also hum the words. Most people who known anything about composers know that Nevin wrote the music, but not one person out of a hundred knows or cares who wrote the words.

The writers of words have just grievance. Nevin could never have written such a song as “The Rosary” if the poem had not given him the idea and inspiration. As Mr. walton says, Alex Rogers wrote the words for “The Rain Song” and “Exhortation,” two of Will Cook’s most famous songs, songs that could not have been written had Rogers not first furnished the idea and inspiration. Mr. Walton himself wrote the words that gave birth to the beautiful little plantation ballad, “Mammy.” But what can Rogers and Walton and the rest of us expect when nobody is even bothered about who wrote the words to “The Rosary”?

There is, of course, an explanation to the whole thing and it is this. Sound has a wider appeal than sense. That is a truth not applicable merely to ignorant people, but also to people of intelligence and good taste. Most people who go to the opera go there not to be stirred by the story and music of a great tragedy, they go to hear a Galli Gurci warble like a bird or to hear a Caruso hit a high C.

Sound has a wider appeal than sense. That is a truth not applicable merely to ignorant people, but people of intelligence and good taste. Most people who go to the opera go there not to be stirred by the story and music of a great tragedy, they go to hear a Galli Gurci warble like a bird or to hear a Caruso hit a high C.

Naturally, I stand with the word writers and say that something ought to be done. At the recitals given in Aeolian Hall and Carnegie Hall a “book of words” is folded in each program, so the listener can see who is the author of the test of the song and at the same time find out what the singer is singing about—more or less necessary arrangement—since most singers do not sing words. But such a method would be too expensive for the average concert; nevertheless, it would be a simple matter to print the name of the lyricist in italics directly under that of the composer and so give him the credit that is due him without taking away any of the honor belonging to the musician.

Yet, I fear, Brother Walton, that you and I and all the rest of the word writers are up against it. I guess these composer fellows feel that we ought to be happy because they allow our names to be printed on the music.