The full-grown Papa Hemingway is a somewhat unwelcome guest these days, with his Trump Jr. penchant for big game hunting and a tendency to lapse into cowboy-movie-Indian dialect when he is attempting to be adorable. When he drifts past, maybe we give a half-wave instead of the customary salute. He scowls back through his beard or raises an elephant gun depending on his mood. In my introductory fiction classes, I still teach “Hills Like White Elephants,” which is, according to several of my students each semester, a story in which a young American tries to persuade his girlfriend to undergo cosmetic surgery; rhinoplasty and breast augmentation are the two most popular guesses. The guessing game goes on until one of the few students who read the story in high school finally lets everyone in on just what the hell it is these two are talking circles around. During this lesson, Hemingway himself sits in the sidecar, practically inconsequential. The point is craft. “Hills Like White Elephants” is a master class in dialogue—in a true feat of literary acrobatics, neither character in this chiseled story ever says one thing they actually mean.

In a more advanced class, I recently assigned “How Do You Like It Now, Gentleman,” Lillian Ross’s New Yorker portrait of Hemingway from 1950. (This is the piece where Hemingway insults Native Americans and all decent persons with his pidgin “Indian talk.”) The assignment had been intended as a tribute of sorts to the recently deceased Ross, but my students only wanted to talk about how Hemingway seemed like, um, kind of a jerk. One student, a particularly bright one who never lacked for insights, simply put her head down on the seminar table and clasped her hands above it. “Oh, c’mon,” I said. “It’s not that bad.” She raised her head and leveled her eyes at me. “I just don’t care about him,” she said. “And what’s more, I don’t like him. I know he’s supposed to be Mr. Great American Writer and all, but there are plenty of other writers to give a shit about, and so I choose right now and forever to not give a shit about Hemingway.” I hemmed and hawed a little, but she had disarmed me, I have to admit.

The problem, I suppose, with becoming great, monumentally great, is that monuments fade from meaning, morphing as the culture makes necessary adjustments, sometimes becoming nothing more than landmarks, places to turn left or right in order to get to our real destination. In our rush to get to where we are going, we do not get up close enough to read the plaques or note the expression on the sculpted marble brow. My students are familiar with monuments; much of their early education has forced them to look upon them. They are bored by these monolithic structures, somewhat, and they are smart and curious enough to question what monuments stand for, and even if they ever should have been built at all. I admire and have learned from them in this, though I sometimes worry about the risk of missing a chunk of our collective story. (Though of course the follow-up question is, and should be, “Whose collective story?”)

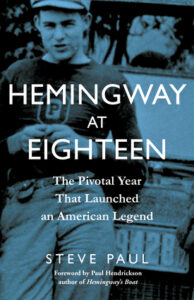

It is useful, then, and maybe refreshing, that a new book by Steve Paul allows us to meet a pre-monumental Ernest Hemingway.

There are essentially two themes at play in Hemingway at Eighteen: The Pivotal Year That Launched an American Legend. The first is how two key events in 1917-18—Hemingway’s fairly brief stint as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star and his enlistment as an ambulance driver for the Red Cross and subsequent injury in Italy—were vital in the development of his famous prose style and in establishing the subjects that would influence his entire career.

One of the delights of Hemingway at Eighteen is in reading some of the pieces that Hemingway crafted during these salad days, working long hours for $15 a week.

The Kansas City material yields copious rewards for Hemingway scholars and aficionados on the hunt for new morsels from the writer’s life. Chapter 2, “Creative Cauldron” follows the teenaged Hemingway through the hallowed doors of the Star building at Eighteenth and Grand Avenue for the first time. Paul guides the reader on a speculative tour of his first day in the pressroom: “[City editor] Longan and his assistant, C.G. ‘Pete’ Wellington, would have pointed Hemingway toward an empty seat to wait for his first assignment, and the young man was made to feel at home as he met some of his new colleagues …” (19) The scene includes a list of these “new colleagues,” men with straight-out-of-central-casting names like Leo Fitzpatrick, Peg Vaughn, Wilson Hicks and Punk Wallace. One cannot help but imagine these denizens of such a uniquely American setting rendered in flickering sepia, tobacco smoke wafting above their hat brims as they jab furiously at the keys of their hulking black Smith Coronas. It is among these newspapermen (and a few women), Paul contends, that the young Hemingway began to forge his straightforward narrative style, with the Star’s venerated editorial guidelines as inspiration. These read like a primer in Hemingway prose, but also carry DNA that would slip into the bloodstream of the American minimalism that came later in the century—one can imagine Gordon Lish consulting the Star’s copy style-sheet as he slashed through Raymond Carver’s stories in the 1970s.

One of the delights of Hemingway at Eighteen is in reading some of the pieces that Hemingway crafted during these salad days, working long hours for $15 a week. Those pieces referenced in the book are reproduced in full in the Appendix, including “At The End of the Ambulance Run,” published in January, 1918:

One day an aged printer, his hand swollen from blood poisoning, came in. Lead from the type metal had entered a small scratch. The surgeon told him they would have to amputate his left thumb.

“Why, doc? You don’t mean it do you? Why, that’d be worsen sawing the periscope off of a submarine!”

Here are the hallmarks of the Hemingway approach—the no-nonsense syntax, the ear fine-tuned for colloquial speech. Another piece, “Mix War, Art and Dancing,” written during Hemingway’s last days at the Star, brought him praise from his fellow reporters. In it, he describes a dance organized for young artilleryman at the Fine Arts Institute, but expands the scope of the narrative to include a lonely prostitute walking back and forth outside on the “wet sidewalk.” Paul writes that Hemingway’s “repetition of the image of the woman walking in the sleet under the streetlamp … would become a familiar, somewhat poetic device in Hemingway’s future work. While most scholars and critics point to the future influence of the repetitive Gertrude Stein in Paris, another theory has emerged recently. H.R. Stonebeck offered the unprecedented suggestion that Hemingway learned much from an important textbook on balladry and folk songs, which was introduced to the young, eager reader in ninth grade. Line repetition is staple of songwriting.” (128) Paul’s skill at synthesizing available Hemingway scholarship with his own research creates a compelling portrait of the artist as a young man, and we can forgive the occasional giddy speculation, as when he suggests (admitting, fully, to fancy) that one of the soldiers attending the dance may have been F. Scott Fitzgerald who was posted at Fort Leavenworth at roughly the same time.

The book has slightly less to offer when it comes to the second half of Hemingway’s eighteenth year in Italy, where he worked for the Red Cross and was wounded (a hair’s breadth away from mortally). Perhaps this is because it is a foregone conclusion that Hemingway’s war experiences and injury would lay the foundation for so much of the work to come, but, beyond this, there is less texture in these chapters than is to be found back in Kansas City, although the research and writing is just as rigorous. It should perhaps come as no surprise that the pressroom chapters are so vibrantly brought to life, causing the chapters set in Italy to pale a bit in comparison; Paul worked at the Kansas City Star for more than 40 years and brings all his senses to bear in his writing about that place.

In any case, Paul lands solidly on his conclusion that Hemingway’s future career was built, at least partially, upon these foundations.

The second theme that runs through the book is perhaps even more compelling. This is the story of how Hemingway began to construct his own monument at a remarkably early age, anticipating, it seems, and perhaps peddling, too, his eventual greatness. The Hemingway we meet in these pages is a boy who has already crafted a fair amount of mythology around himself, who believes wholeheartedly in his own exceptionalism (“… the Lord ordained differently for me,” he writes in a letter home), who makes himself the subject of a series of inside-jokes with family and friends, and who is not unwilling to allow his own vainglorious romantic daydreams, and even the exploits of others, to be interpreted by those around him as the truth or something close enough to it.

Paul recounts the writer’s own story of a fistfight, later disputed, “when Hemingway supposedly rose to protect the honor of Leo Fitzpatrick from a knife-wielding waiter, who’d misconstrued an order for milk toast. Curiously, Hemingway obscures who did what to whom …” (169) I am reminded here of a line in Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused (1993), in which nerdy high-schooler Mike Newhouse, played by Adam Goldberg, explains how a beating he just took at the hands of a school bully might make its way into lore: “I read about like a Jackson Pollock or Ernest Hemingway, you never read who won or lost, just they got into a brawl.”

Remarkable as well is another account of Hemingway’s manipulation of the truth in service of his nascent legend, here involving a silent film star, Mae Marsh, whom he may have encountered while covering vaudeville for the Star. Hemingway allowed his infatuation with Marsh to escape the confines of his imagination, creating a ruse of an engagement that startled his family and friends when he wrote to them of it:

[Hemingway] confided in one of his Star colleagues that he blew the cash his father had given him on an engagement ring. “Miss Marsh no kidding says she loves me,” he would tell Dale Wilson in May. “I suggested the little church around the corner but she opined as how ye war widow appealed not to her.” Decades later, Wilson finally did what any reporter worth his salt would have done. “It took me forty-eight years to finally get in action and check the accuracy of that engagement. I phoned to California in 1966 to Mae Marsh, the movie queen of The Birth of the Nation … ‘Did you ever meet Ernest Hemingway?’ ‘No,’ she said, ‘but I would have liked to.’ It would seem that Reporter Hemingway in that 1918 letter was trying out his fiction writing on us back in Kansas City.” (103)

In the above, it is not so much that Hemingway imagines himself into a scenario with a movie star—any teenage boy might do as much—it is that he is able to picture himself as her beau so clearly and unquestionably that he offers it to others as indisputable. Whether it is true or not did not really matter, the damage, as it were, was done. Reading, I recalled Hemingway’s future mentor Gertrude Stein’s reaction to Picasso’s portrait of her. “Well, it doesn’t look like me,” she is alleged to have said. Picasso’s reply: “Oh, it will.”

The Hemingway we meet in these pages is a boy who has already crafted a fair amount of mythology around himself, who believes wholeheartedly in his own exceptionalism, who makes himself the subject of a series of inside-jokes with family and friends, and who is not unwilling to allow his own vainglorious romantic daydreams, and even the exploits of others, to be interpreted by those around him as the truth or something close enough to it.

Such a hands-on/hands-dirty approach toward forging a legend casts Hemingway as an early architect of a particularly modern, Warholian, brand of fame, one that would eventually evolve into the “fake it until you make it” Instagram-ish celebrity that dominates our culture today (and which brought us, among other prizes, a President Donald Trump).

Indeed, it is amusing to page through the portfolio of photos in the center of the text, filtering them through a contemporary lens of selfies and status updates. Here is the 18-year-old Hem leaning back on the hood of a car in a family portrait, his legs comfortably crossed, a rakish cap on his head, his expression a forthright smile/scowl; here he is beaming and presenting a freshly-caught trout; here laying on his side in a hospital bed in Milan, his leg humongous with bandages. In all of these photos, Hemingway appears not to look not into the camera, but instead directly into the eyes of a future audience he is certain will look back. (Is there a hint of something else, too—the unbearable sadness and loneliness that will lead him, finally, to that room in Ketchum with a shotgun in his hands?) Is it possible I am reading too much into this? Sure. However, that Paul has created a space for such musings with this book, and in this way cleared a new path to an overgrown and foreboding monument, is much to his credit.