Several years ago the writer was in one of the Latin-American capitals while the first blow struck against Spain for national independence was being celebrated. After a torchlight procession speeches were made in the plaza to an immense crowd. There were the usual rhetorical allusions to the dead heroes and their struggle for freedom, but the crowd was not stirred to its greatest outburst of approval until one of the speakers made some remarks antagonistic to the United States.

This incident occurred in a country which did not then have and never had had any serious national grievance against this country. I was not very much surprised, for it is common knowledge among Americans who have lived for any length of time in the countries of Central or South America that there exists among the natives there a smouldering dislike for the United States, which upon the slightest sort of provocation is likely to flare up and show itself. These Americans also know that, despite official protestations of friendship, the United States stands lower in the affections of the Latin-American people than Spain, France, Italy, Germany or England.

This feeling of special dislike is curious when it is considered that the attitude of the United States has always been that of friend and protector, and that the independence, the very entity of these southern republics, has depended upon that attitude. On the other hand, various ones of these same republics have been threatened and coerced and even have had ports bombarded by European powers.

These Americans also know that, despite official protestations of friendship, the United States stands lower in the affections of the Latin-American people than Spain, France, Italy, Germany or England.

This feeling of hostility and seeming ingratitude has puzzled a great many Americans, especially American officials; and various explanations of the cause have been made. One of these explanations is that the people of Latin America have grown to fear that the United States has designs upon the integrity of their several governments; but the past and present policy of the United States does not warrant any such fear. Another is that the bond of language, religion and mode of thought naturally draws the Latin-American closer to the Latins of Europe; but this bond would not account for the lack of an undercurrent of feeling against Germany and, much less, against England. A third explanation offered is that the American who goes into Latin-American countries does not take the proper steps to cultivate friendly feelings, that he holds himself aloof, that he reveals his prejudice, and so engenders dislike. It is true that the Frenchman, Spaniard, Italian and German who lives in Central or South America and does business there often intermarries with natives and makes himself, socially, one of them; but the Englishman generally holds himself more aloof than the American, yet there does not exist against Englishmen the feeling that exists against Americans.

This third explanation comes closer than the other two, still it misses the mark. No doubt, there have been Americans who were narrow and prejudiced, and ill-bred enough to show it; but several hundred American residents, businessmen or salesmen, scattered through a foreign country and devoid of any official authority, attempting to assume airs of superiority over the natives would have very little effect, indeed, they might appear ridiculous. Moreover, the writer during his eight years of experience has observed that the great majority of Americans who have business dealings in Latin-American countries are able to overcome, or at least hold in abeyance, any prejudices they might have.

This feeling of hostility and seeming ingratitude has puzzled a great many Americans, especially American officials; and various explanations of the cause have been made.

The deep-seated cause of this feeling of hostility does not spring from the actions of Americans who go to Latin-America but from the treatment accorded to Latin-Americans who come to the United States. In truth, the whole question is involved in our own national and local Negro problem.

The Latin-American people, by an overwhelming majority, are not white people, and decidedly not in the American sense, and a number of them, people of wealth and refinement, who have come to the United States and been treated like “niggers” will never be known. The same people have gone to Europe—for the Latin-American of means makes travel his chief diversion—and noted the difference. These travelers have returned home and facts concerning the treatment accorded in the United States to a dark skin have been disseminated with something of masonic secrecy. This secrecy is what has made the whole question puzzling. The Negro in the United States loudly sets forth his wrongs, but whatever the Latin-American has suffered at the hands of Americans on account of race discrimination he neither discusses or even openly admits. Of course, the position of the two groups is far from being identical. For Latin Americans, citizens of independent and sovereign nations, to complain of race discrimination against them in a foreign country, would be to attach to themselves, in some degree, the stigma of inferiority. The Latin Americans understand this and adopt other measures.

In only one way do they take any cognizance of this question and that is through indirect reference to it in the Latin-American press. Any observation of the newspaper of the capitals of Central and South America will show that these publications make a point of giving space and prominence to lynchings and other outrages perpetrated against Negroes in the United States, even though these outrages may be committed in most obscure communities; and this is often done to the exclusion of other and more important world news. It appears that they cull the American newspapers for these items; the writer has seen as many as three in a single issue of a Latin-American paper. No comment on them is ever published, but they always carry a silent warning.

The Latin-American of means and refinement is an exceptionally proud and sensitive man, and prizes his individual honor and self-respect above any general conception of patriotism. In a choice between the loss of national sovereignty and the loss of his individual honor, self-respect and his status as a man he would undoubtedly accept the former; and any affront to the latter is something he will not forgive.

Ugarte, the well-known Argentine patriot and agitator, has traveled through Mexico, Central and South America, laboring to awaken the people of those countries to the danger of imperial aggression on the part of the United States, but that danger does not appear to be sufficiently imminent to constitute the chief motive for this propaganda. Senor Ugarte, whom the writer had the privilege of talking with about a year and a half ago, is himself a man of brown skin, and it is not unreasonable to judge that the fear that lies closest to his heart is not that southern republics will lose their independence to the United States, but that they will fall under the bane of American prejudice, a process which he has without doubt, observed going on slowly but surely in Cuba, Puerto Rico and Panama.

The Latin-American of means and refinement is an exceptionally proud and sensitive man, and prizes his individual honor and self-respect above any general conception of patriotism.

It is idle for the United States to dream that, either through the Monroe Doctrine—which is sometimes spoken of more disparagingly in South America than in Europe—or through diplomacy, or its Bureau of American Republics, or efforts for closer trade relations, it will win the absolute confidence and good will of Latin-American people so long as there is in this country a Negro problem.

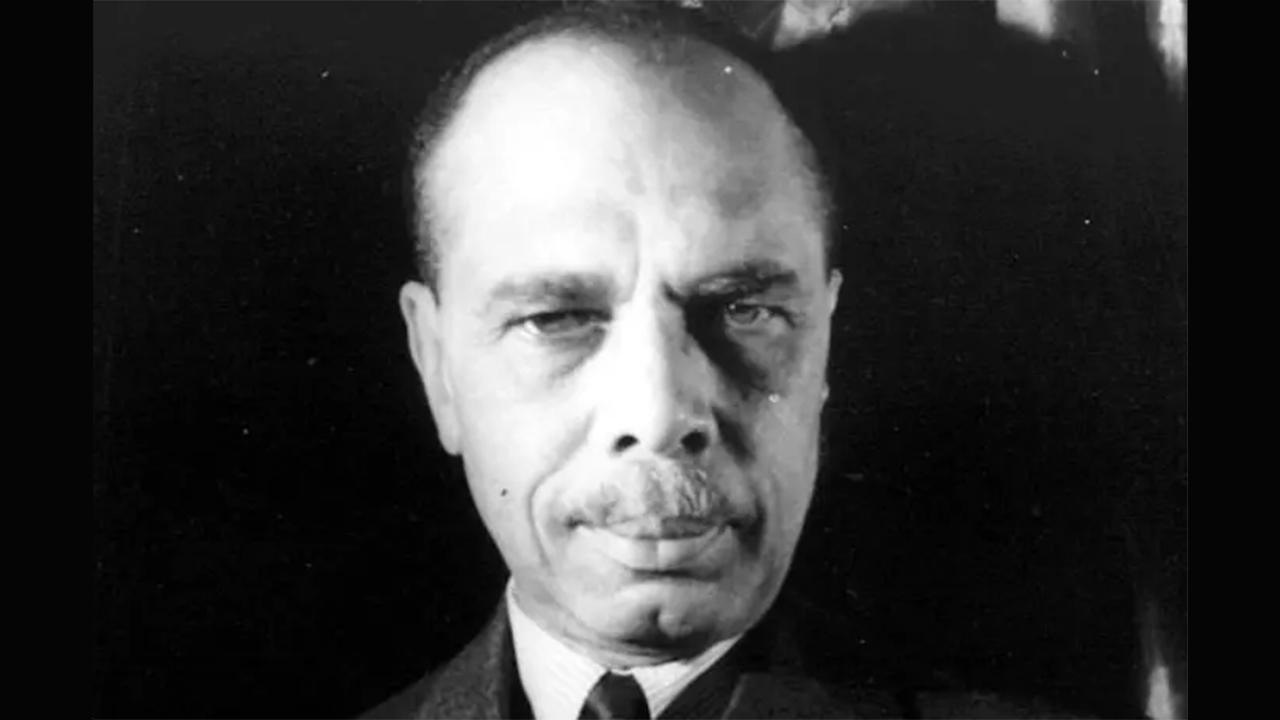

Editor’s note: Throughout the original essay Johnson hyphenates Latin-America, Latin-Americans, and Latin-American.