The Weight of Obsession

A brief, but wide, history

By David Haslam

May 8, 2015

The English Surgeon William Wadd wrote the first book dedicated to obesity in 1810. He knew the answer to the modern obsession with his chosen subject:

“[In] Vastness, whatever be its nature, there dwells sublimity. Why, therefore, may not the mountains of fat, the human Olympi and Caucasi, excite our attention? They fill a large space in society, are great objects of interest, and ought to afford us no small matter of amusement and instruction.”

He compared human obesity to the highest mountains and the Great Pyramids of Egypt, but could just as easily have mentioned cars, penises or skyscrapers to define the nation’s obsession with size. The obsession with obesity however is complex; as well as a fascination with large individuals, there is obsession with the causes of obesity—food, computer games, television, and as Wadd suggests, the need to stare at fat people; both voyeurism and exhibitionism exist. As now that obesity is far from being the rarity it once was, the modern obsession reflects that ubiquitousness, and has required new heights of sublimity and more bizarre methods of depiction. As what was once a rare phenomenon has become normal, only super-vastness fascinates us.

Statisticians are obsessed with obesity; the prevalence of excess weight in the United States is 68.5 percent of the population; 34.9 percent are obese. Obesity kills more people in the developed world than terrorism, climate change HIV or war. The current adult population of the United States will lose more than a billion cumulative years of life as a result, enough to take the Earth back to when life comprised only a few multicellular plants.

Now that obesity is far from being the rarity it once was, the modern obsession reflects that ubiquitousness, and has required new heights of sublimity and more bizarre methods of depiction.

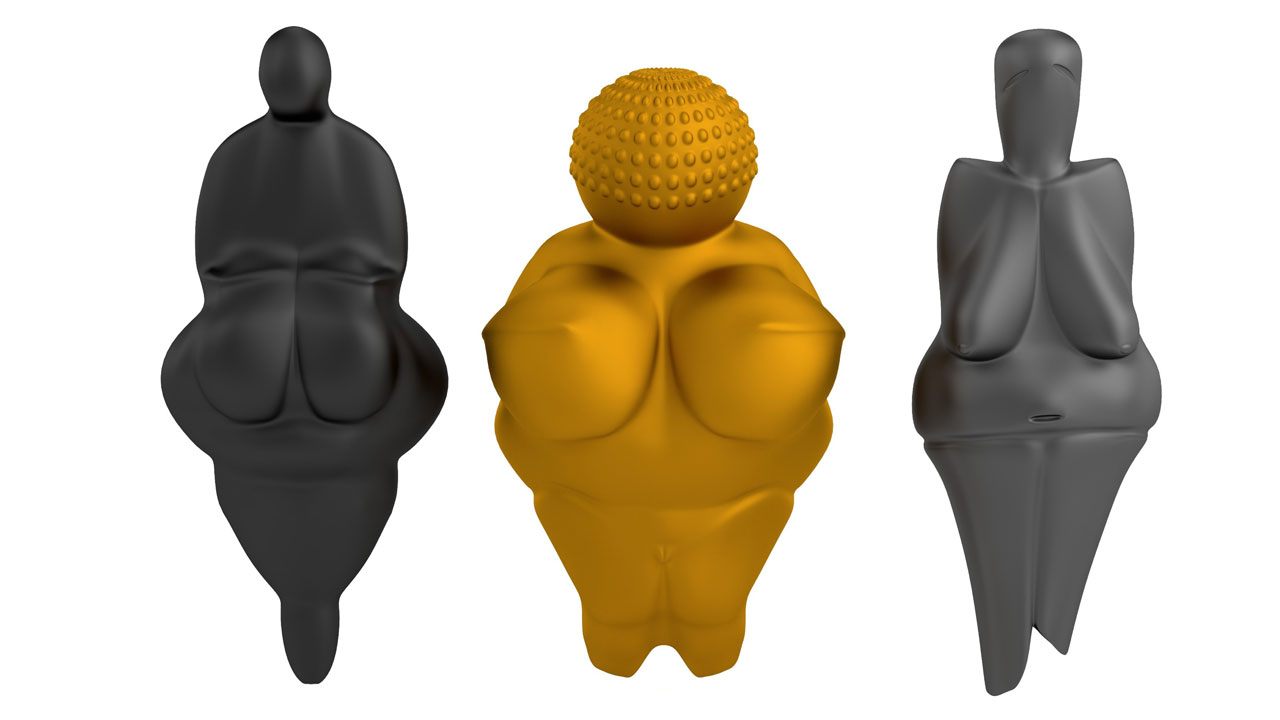

The developed world’s obsession with obesity has been ingrained in our culture for tens of thousands of years, so there was never a chance of modern America escaping it. Prehistoric man was enthralled. Even hominids found rocks in streams which resembled obese people and added crude features to them to make them more life-like. The Venus of Berekhat Ram from the Golan Heights, for example, dates from somewhere between 230,000 to 500,000 B.C.; the Venus of Tan-Tan from Morocco is a relic of the early to mid-Acheulian period. These could not have been the work of homo sapiens, but homo erectus. Could homo erectus have been as obsessed with weight as modern America? Comparatively recently, ancient man created figurative art from his own imagination. The Venus of Willendorf, 25,000 years old, was considered the oldest piece of figurative art on Earth; an anatomically accurate depiction of an obese woman with no face, plaited hair and hands resting on her breasts. “Unequalled in the cultural history of mankind [she] stands at the beginning of artistic creation and [her] position in the world of arts is unparalleled.” Theories abound; was she a self-portrait, hence the lack of facial features? Commonly thought to be a fertility symbol—the Mother Goddess; theories that she is pregnant seem unlikely given her obese thighs and obvious visceral fat. Typically the French have their own take on the matter, describing her as “prototypes paléolithiques de la playgirl du mois.” Modern America is fascinated by this curious European relic “carved from a hunk of limestone, shaped into a blues singer. In her big smallness she makes us kneel.” In May 2009 the discovery of a mammoth-ivory figurine from the basal Aurignacian deposit at Hohle Fels Cave in southwest Germany was reported, at 10,000 years older than the Willendorf Venus. Remarkably, once more it depicts an obese woman, her features pornographically exaggerated in grotesque fashion. That many of the oldest statues on Earth depict obese women indicates a deeply ingrained obsession. The name “Venus” is ubiquitous in describing these figures; said to be an example of Austrian sarcastic humor, as, clearly such obese figures could never be deemed beautiful. The obsession was widespread; obese “Venus” figurines have been discovered across Europe, thousands of miles, and thousands of years apart. Possibly the most exaggerated Venus figure is the 30,000 year old Monpazier statuette; buttocks, breasts, thighs and vulva prominent showing a remarkable resemblance to the so-called “Hottentot Venus” Saartjie Baartman, who was a Khoisan girl from the Gamtoos River region of Africa who displayed steatopygia—exaggerated, obese buttocks and elongated labia—demonstrating profound ethnic differences, which perplexed, fascinated, and horrified Europeans in the early nineteenth century. Exhibited throughout Europe in life and as anatomical specimens after her death at 35, Saartjie’s buttocks represented evidence of the contemporary belief of African women’s excess, deviant exaggerated sexuality. Cambridge anthropologist Paul Mellars explains: “If there’s one conclusion you want to draw from this, it’s that an obsession with sex goes back at least 35,000 years. …. if humans hadn’t been largely obsessed with sex they wouldn’t have survived for the first 2 million years.” Thus obesity and sex have long been linked and deeply entrenched in history, and in many different cultures. The Jewesses of Tunis were fattened for the benefit of men “when scarcely ten years old … by confinement in narrow, dark rooms, where they are fed on farinaceous foods and the flesh of young puppies until they are almost a shapeless mass of fat.”

The Venus of Willendorf, 25,000 years old, was considered the oldest piece of figurative art on Earth; an anatomically accurate depiction of an obese woman with no face, plaited hair and hands resting on her breasts.

One particular aspect of the Venuses is shared incessantly throughout literature, science and culture through the ages; that of exaggeration—usually the Venus statuettes had oversized breasts, and genitals. A literary character such as Count Fosco in Wilkie Collins’s novel, The Woman in White (1859), Ursula the pig woman in Ben Jonson’s play, Bartholomew Fayre (1614), Mrs Gamp, from Charles Dickens’s novel 1844 novel Martin Chuzzlewit, or Mrs Musgrove in Jane Austen’s 1818 novel Persuasion may become even more powerful, formidable, greedy or grotesque given 100-pound extra weight; their deeds more despicable, romantic or corrupt. In art, corpulence is a powerful symbol; what would Bacchus have represented had he possessed a formidable six-pack? Botero’s characters are only of such interest for their weight. Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Jenny Saville have painted exaggerated obese subjects.

In the mid-19th century two industries started to flourish; anti-obesity remedies anticipating the current simultaneous obsession with leanness; and the trade of exhibiting obese people as circus freaks for profit.

Quack remedies; obsession with drugs

The cash-in of manufacturers of obesity remedies was corrupt and deceitful from the 19th century onwards and continues to be so with the occasional exception. Eventually designated as quack remedies and nostrums, companies made huge profits at the expense of a vulnerable, obsessed public, deceived by unregulated adverts in the increasingly available newspapers of the time. Since Hippocrates, Galen, Avicenna and Sushruta first pioneered the treatment of obesity, some of the most dangerous toxins have been used as weight-loss remedies: poke berry, arsenic, mercury, strychnine and dinitrophenol—usually successfully for weight loss, but often fatal. Conversely quack remedies have been and are still being fobbed off to the unwary for centuries, usually doing little harm, but without benefit. One drug—Antipon—was advertised in the newspapers, and available by mail order to rich, corpulent Victorian men and women. Publicity material boasted “a guaranteed permanent elegance and assured physical beauty.” “Antipon; King of Corpulence Cures:” weight loss “without irksome dietary restrictions” or other forms of hard work. “No distasteful dietary restrictions are enjoined. … Stout readers are earnestly entreated not to trifle farther with drugging, sweating and half-starving.” Antipon was later analyzed by the medical authorities and found to have no active ingredients whatsoever. “Fatoff” was claimed to be a soap fortified with the newly discovered thyroid hormone, to be massaged into the neck to treat double chin. It contained only soap. Possibly the most audacious attempt to fool the gullible public was Human Ease, from Atlanta Georgia; “cures all known diseases both in and on man or beast … take human ease, you can eat what you please;” a cure for obesity, TB, diphtheria, mad dog bite, cancer and much more. On analysis by the American Medical Association, it was found to contain almost pure lard.

In the 1940s America became bewitched with amphetamine; developed originally as a decongestant and used for narcolepsy and neurotic depression, its weight loss properties did not go un-noticed. In 1962 the market was flooded with amphetamine and related products, often in combination with barbiturates to avoid agitation. Eighty thousand kilograms were manufactured each year, the equivalent of 43 tablets per person per year across the entire population. By the late 1960s up to 10 billion amphetamine tablets were being manufactured in the United States—a private physician would pay $71 for 100,000 tablets and sell them for $1,200. Only in the early 1970s was the full extent of amphetamine toxicity and addictiveness being realized; sinister voices would emanate from toilet bowls, and paranoia would develop in amphetamine psychosis.

Obesity on display

In the late 1800s obesity was still uncommon, and often a sign of wealth; enough money to eat well, and sufficient status to avoid wasting diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis. Cases of severe obesity, such as Daniel Lambert, Monster Miller, and Edward Bright had attracted fame and notoriety in previous centuries. A man known only as G Hopkins, weighing 980 pounds was displayed at a London Fair in the 1700s alongside a prize sow and her piglets—whilst reaching for a distant morsel of food he is said to have toppled, killing the whole porcine family. But soon every circus, carnival, midway and “dog and pony” show needed a “fat freak,” their caller announcing “Oh they are fat, so terribly, terribly, terrifically fat.”

In the 1860s the New York Clipper entertainments newspaper advertised the chance to see John Powers, the Kentucky Fat Boy with his older, heavier sister, Mary Jane, who was exhibited at P. T. Barnum’s New York Museum in 1867. John weighed 485.5 pounds at age 17; Mary tipped the scales at 782 pounds, at 5 feet 2 inches, over 14 inches shorter than her brother. Mary Powers was the fat lady in residence at Barnum’s Museum when the great fire of 1868 razed the building and persuaded Barnum to tour as a circus instead. The Powers siblings set up their own travelling show in Cincinnati, playing fairs with a midget and two bears, before eventually settling in Philadelphia as museum exhibits.

The woman possibly most qualified to be called the first circus fat lady was Hannah Battersby born Hannah Crouse in 1842 in Vermont. She probably started her career as an exhibit in 1859, weighing 500 pounds, and at her peak up to 800 pounds. She married John Battersby, the Human Skeleton, and died in Frankfort, Philadelphia, in 1889. Rare photographs of Hannah and John reveal the exaggerated extremes of their body morphology, and pictures of them together contrast Hannah’s buxom curves with John’s bizarre skeleton.

The display of human oddities, especially those displaying flesh, became more profitable and during the 1880s and 1890s, “dime museums” became popular attractions, often occupying several stories of a building, displaying permanent artifacts as well as performers and a theatrical show. Another fad was fat lady “conventions: Managers booked in half-a-dozen fat ladies and featured them in various contests—the 50 yard dash in the street outside the museum always drew large crowds.”

A particular aspect of the display of obese individuals was the exaggeration of their weight and personal circumstances, and the bizarre contrived situations they were forced into. Like Hannah Battersby, her advertised weight bore no relation to her actual size. American adolescents and children were not exempt from display; Lovely Lucy Moore at least attempting some exercise on her roller skates, billed as weighing 668 pounds, appeared to be less than half that size. Fat Man Chauncey Morlan, wore flouncy exaggerated costumes and married Annie Bell, the circus fat lady who wore equally extravagant clothes. Four hundred fifty-three pound Fred Howe, 5 foot 4 inches, was set up in a boxing match with the circus giant George Moore, 7 foot 2 inches and 110 pounds. In a scenario reflecting Hannah Battersby’s marriage to John, the human skeleton, John Craig married the midget Little Princess. The Circus Scrapbook in 1929 described a show, and documented early changes in America’s attitudes:

“Although the side-show will last as long as the circus itself, I regret to say, that some of the traditional features are losing interest. The fat lady, for instance, is ceasing to interest the public. In the old days no show was complete without her. Thirty years ago, there was a famous rivalry between two famous fat women. They were Kate Keathley and Hannah Battersby. Each weighed 400 pounds, and each got a dollar a week for every pound they carried. Once they got into such heated conversation, that it led to a fight, but there was so much body space between the combatants, that they could not reach each other with their arms. Besides, the exertions threatened them with heart seizure, and their managers were loath to lose such a profitable asset. Most freaks make equally freakish marriages, and it followed that Hannah married a Living Skeleton, who weighed sixty-five pounds. The alliance was happy and for years they occupied adjoining platforms in the Barnum sideshow.”

More recently obsession with obesity has developed in a more overtly sexual way. The display of fat for sexual pleasure coincided with the heyday of the circus midway; like the tattooed lady, the fat lady could show a little bit more flesh than usual, and punters were even allowed to touch before moving on to pull the whiskers of the bearded lady. It was deeply arousing to Victorians to get the opportunity to feel strange women in a quasi-legitimate, respectable setting, and it was a tantalizing and disturbing sight for the other spectators, especially adolescents. A wondrously titillating dialectic emerged; performers were perceived to be alluring as well as repulsive. Circus fat ladies of the era were described as “the most erotically appealing of all freaks, with the possible exception of male dwarfs.” At the same time saucy seaside postcards began including rotund sexual stereotypes alongside juvenile double-entendres.

Helen Melon, aka actress Katy Dierlam, performed at Coney Island in 1992 as a fat lady to recreate the lost appeal of the Carnival Midway era. She vigorously displayed the sexuality suggested by her stage name; her opening routine involved touching her breasts and shimmying her hips: “Take a good long look!” Alice Wade—“Alice from Dallas”—in her cartes de visite, does not portray a prudish young woman, more a sexual invitation, reclining on a couch in a skimpy silk negligee revealing bare arms and thighs. What could Winsome Winnie have expected to win apart from sexual attention as she gratuitously raises her tunic above her naked thighs? In later eras, performers such as Dainty Dotty and Miss Baby Dumpling were more overtly provocative, appearing naked behind fans, “400 lbs of fun.” Helen Melon theorizes about the eroticism of the fat woman as “the memory of having been cuddled against the buxom breast of a warm, soft Giantess, whose bulk, to our 8 pound, 21 inch infant selves—must have seemed as mountainous as any 600 pound Fat Lady to our adult selves.” Psychologist Mildred Klingman explained the sexual dynamics whereby a man is attracted to a fat woman. “There are many such men. … ‘Sure I like ’em big. I don’t want to have to shake the sheets to find my woman.’”

The sexual obsession

In Tim Burton’s 2003 film Big Fish, Bruce Snowden plays himself as the circus fat man, but has since passed away, symbolizing a dying breed. In contemporary times, obesity in America has become commonplace, so the concept of “vastness” has had to grow proportionately to keep it far enough distinct from normal to maintain its sublimity. Instead of postcards of obese circus performers, there is super-obese pornography on the newsstands in DVDs such as Chunky Chicks, and Scale Bustin’ Bimbos featuring SSBBWs—super sized big beautiful women. The stomach and breasts are usually the focus; photo shoots often involve the exuberant and erotic use of food, often cream, ice cream, syrup or spaghetti and food entering the mouth is a substitute for penetration. Daytime TV host Vanessa Feltz has described the attraction between small men, and obese women as the only genuine display of true affection: “Men who genuinely love women fantasize about being smothered in sofa-sized breasts and pillowed in marshmallow thighs. Pert is OK but pneumatic is heaven. Not for them the bite-sized morsel. They revel in handfuls, fistfuls, and armfuls of lusty lady.”

A woman who becomes aroused by being fed is a “feedee,” and the person supplying nourishment a “feeder:” although the feeder-feedee relationship may not be overtly sexual, erotic undercurrents exist. The ultimate expression of commitment between feeder and feedee is the achievement of the state of ‘immobility’ whereby the feedee relies exclusively and comprehensively on the feeder, as a baby to its mother. At 500 pounds, Supersize Betsy is a feedee and was interviewed by the journal RE/search, claiming to be waiting for the right man before finally submitting to immobility. “I wouldn’t want to put it on casually:” “All of [my admirers]—down to the very last one—have some kind of fantasy of me sitting on top of them or laying on top of them or just enveloping them. To them, it’s like being smothered in chocolate syrup. It’s not a death wish or suffocation thing—it’s more about being able to feel this femininity surrounding you completely.” Jeb is a feeder and finds female fat comforting—“like a big, soft feather bed I can fall asleep on.” He likes to nuzzle his face in his partners teats and belly, speaking hopefully of a day when he’ll be able to get “swallowed up in her fat” as if she were an amoeba and he a food particle.

Food obsession

An obsession with obesity is entirely different from obsession with the cause. Food may not be the only culprit in obesity, but its fingerprints are everywhere, and overconsumption is deeply ingrained in developed culture. In ancient Ayurvedic medicine, the great physician Sushruta blamed obesity on sedentary lifestyle, pampering the belly, sleeping during the day, and avoiding “any sort of physical exercise.” In diverse cultures over different centuries obesity has been recognized and linked to too much food; Avicenna in 1000 A.D. “Most illnesses arise solely from long-continued errors of diet and regimen;” Rhazes gave a description of obesity—“saman-e-mufrat”—and the link with gout to “stoutness of the body,” Maimonides, also known as Rabbi Moses Ben Maimon, or Rambam, born 1135, had an interest in diet and public health, echoing Hippocrates and Galen. However the Ancient Egyptians probably pioneered deliberate overeating as opposed to inadvertent unhealthy eating, controlling their calorific intake by intermittent vomiting and purging. But the Western World’s obsession with gluttony and voracious appetite for food arguably began in Rome, the “parasitic fat shining spider at the centre of the web of the Roman empire.” A typical menu was “Whole boar, goose, foie gras, peacock and Trojan pig stuffed with all kinds of sausages, vegetables and surprises,” a cuisine now often referred to as pretentious and disgusting—overspiced with unspeakable zests and extracts, putrid with abominable sauces … malodorous concoctions linked with sexual deviations at the bath house. ‘The oligarchy pink and plump reclining before mounds of food while eunuchs stroke oil into their skin; others vomit.” Perhaps having learned from the Romans, affluent mediaeval Britons provided similarly lavish feasts; the marriage banquet in 1243 of Henry III’s brother Richard comprised thirty thousand dishes. Over the centuries spectacular examples of obsessive and bizarre eaters have occurred; the gluttonous feats of the Great eater of Kent are recorded in great detail by the incredulous author, the Water Poet, John Taylor:

“Once at Sir Warham Saint Legers house, and at Sir William Sidneys he shewed himself so valiant of teeth and stomach, that he ate as much as would well have served and sufficed thirty men, so that his belly was like to turn bankrupt and break, but that the serving-men turned him to the fire, and anointed his paunch with grease and butter, to make it stretch and hold.”

Taylor describes how Wood was defined as a Tugmutton or Mutton-monger, for his ability to eat a whole sheep raw at a single meal except for skin, wool, horns and bones.

There are a host of different eating disorders that have been suggested, such as hyperphagia (eating everything whether edible or not), coprophagia (feces eating) and anthropophagy (cannibalism). One insane cannibal amongst many, called Menesclou, was caught with a missing girl’s forearms in his pocket, and her head and half-burnt entrails in his stove. His defense was that there had been an accident. This year’s American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-V listing, categorizes more eating disorders than ever before; however, historically the American Dr Albert “Mickey” Stunkard started the ball rolling and first formally described binge-eating disorder, in the middle of the twentieth century. In “The Pain of Obesity” he wrote about the patient who made him consider its existence, a man named Hyman Cohen: “Everything seemed to go blank. I just said ‘What the Hell’ and started eating.” He started with cake, pieces of pie and cookies, then set out on a furtive round of the local restaurants, then went to a delicatessen, bought another $20 of food “until my gut ached. I’ll drink beer, maybe six or eight bottles to keep me going, then I’ll want more food. I don’t feel in control any more. I feel like Hell. I should be punished for the shameful act I’ve performed.” Although binge eating disorder is clearly a medical condition the American obsession has managed to turn gluttony into an ultimate challenge. Most Americans will be aware of the Heart Attack Grill in Downtown Las Vegas, where customers are wheeled in wheelchairs by ‘nurses’ to their table; where quadruple bypass burgers are the ultimate feast, where checks are not accepted because the payer is unlikely to still be alive when the check reaches the bank, and where a person over 350 pounds eats free. This author has a BMI of 29 when last measured, and his entire family of five failed miserably to reach that target. Now, at last, gluttony has achieved the pinnacle of a modern American obsession: as a professional sport. The International Federation of Competitive Eating (IFOCE) has a motto “In voro veritas:” “In gorging, truth.” Eating competitions were possibly first described in Norse epic poetry. In The Edda, the God Loki loses to a giant, as although both ate all their meat, the giant ate his plate as well. Then in 1995 the Virgin Mary’s image appeared in a grilled cheese sandwich in Florida, a sandwich which later sold for $28,000 on eBay. This sandwich has spawned a speed eating competition—The World Grilled Cheese Eating Championship at Venice Beach—and has been exhibited ever since, the sandwich being raised in the air to herald the start of competition—“the culinary shroud of Turin”—to the cry of “The passion of the Toast lives.” Sonya Thomas—the “Black Widow”—at least defeating the American stereotype in one way, weighing 103 pounds at 5 foot 5 inches—wins, eating 25 sandwiches in ten minutes, then eating the twenty-sixth as a celebration.

Although binge eating disorder is clearly a medical condition the American obsession has managed to turn gluttony into an ultimate challenge.

In ancient history our knowledge of obesity depends on interpretations of ancient artifacts. The Chinese emperor Qin was buried with at least 8,000 individually crafted terracotta images of his soldiers, generals, chefs and servants, in order to serve and protect him in the afterlife. Faces, clothes, hairstyles and body morphology were unique to each image. The 2,200 year old individuals are known as the Eighth Wonder of the World. Buried with the Emperor to ensure his prolonged post-mortem high status in the afterlife, most characters are military: others are accountants and administrators. Of all the thousands of statues, only one is obese: the Entertainer—included to ensure the Emperor could still enjoy a good laugh at someone else’s expense.

In modern representation of the arts the symbolism is easily accessible; one of the earliest cinematic appearances of any character is “fat man on a bicycle;” a representation of Pimple, a fat man, more correctly falling off a bicycle into a fruit barrow and a baby’s pram. Later the obese Oliver Hardy would stand pompously while Stan Laurel scratched his head and burst into tears, an automobile tire rolling in from stage left. Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (1887-1933) was a huge star before outrageous accusations of rape and manslaughter finished his acting career. Obesity in the art of cinema has progressed through sinister representations of powerful corpulence in the shape of Alfred Hitchcock as himself, Orson Welles in Citizen Kane (1941), and Marlon Brando as The Godfather (1972). More recently though modern American stereotypes such as Robin Williams’s Mrs Doubtfire (1993), John Belushi’s Bluto from National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978) and Eddie Murphy’s Nutty Professor (1996) and Norbit, and Martin Lawrence’s Big Momma’s House films (2000, 2006) have colored the water, somewhat trivializing obesity. These movies, plus TV shows such as “My 600-lb Life” and “Half Ton Man,” about Patrick Deuel, the world’s largest person, demonstrate that the sensationalism of the freak show is still alive, even exaggerated. In art, the obese stereotype has been more empathetically expressed, if equally exaggerated, by Fernando Botero (“Boterismo”), Jenny Saville and Lucian Freud.

The All-American art of extreme exaggeration is possibly no more evident than in comic book culture—where real-life is irrelevant and outrageous stereotypes thrive. The Judge Dredd series portrays a community of super-obese individuals who, having terrorized a community by stealing food from equally starving normal weight individuals, eventually become heroes by being able to walk a few competitive yards with wheels attached to their overhanging abdomens. Captain Obese was an American loser, derided because of his obesity, who travelled through a space-time continuum to a planet where obesity was treated as a divine characteristic, and became a super-hero as a result. Billy Bunter, the English Public School anti-hero, is nothing more than a fat buffoon. Comic book culture doesn’t seem to be able to decide the rights and wrongs of obesity, just as the national media prevaricates. Newspapers display an ambivalent attitude towards weight; sometimes it sensationalizes obesity, at other times it sympathizes. Often it is judgmental and discriminatory, but sometimes its role is to educate and inform. Every few months a front page headline will teach us about a “Weight Loss Wonder Drug” or “Miracle Pill” whereas the next day is an article deriding a fat person’s lack of will, social conscience and responsibility—stories of greed and gluttony as they are taken into an ambulance through a hole in the wall of their house. The freak show is alive and well and bigger than ever.

Others have an obsession for obesity denial. Paul Campos is among many who deny that obesity deserves medicalizing or treating. He has written a “backlash” entitled The Obesity Myth: Why America’s Obsession With Weight Is Hazardous to Your Health (2004). Here he dissects the vagaries of the way we measure obesity, correctly pointing out that BMI is flawed, and obliquely referring to the obesity paradox, which describes the concept that although obesity may lead to conditions such as heart and renal disease, its presence may be protective once the condition has been diagnosed. There is some merit in this idea of a paradox; Carl Lavie is in the forefront of its investigation. It may be because “normal” weight is caused by smoking, stress or concurrent disease, or that obese individuals are more likely to have been treated with statins and anti-hypertensives earlier because of their obvious higher risk. The paradox aside, no physician worthy of the name would ever claim that obesity is a good thing, witnessing the prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, dementia, cancer, sleep apnoea and liver disease seen in clinic every day, directly attributable to excess weight. Paul Campos is a lawyer. His adversarial proclivity is clearly an occupational necessity.

America’s obsession with obesity has spawned some excellent and compelling best-selling books, each of which unveils a different definitive answer to the problem; Nina Teicholz Big Fat Surprise (2014), Robert Lustig’s Fat Chance (2013), Gary Taubes’ Good Calories, Bad Calories (2007) and many more. Three thousand years ago Hippocrates said “the body is like a ship that should not be overloaded.”

Has anyone come up with a better answer?