List(ing) to Port

I always love it when, at a critical moment in Fred Schepisi’s 1990 cinematic adaptation of John Le Carré’s 1989 novel The Russia House, a British secret intelligence officer named Ned—only Ned (James Fox)—declares, “I don’t like lists.”

I share this sentiment, especially regarding lists that claim to compile the “Ten Best Films of the Year” and the “One Hundred Best Novels of All Time.” Such rankings exclude far too many worthwhile texts while conferring upon their makers a dubious reputation for special wisdom about the best art in any given field, form, genre, or medium. These inventories consequently assume, far too frequently and much too easily, the patina of unassailable truth even if everything about them remains subjective, arbitrary, and individual. Asserting that such compendia form definitive—to say nothing of final—pronouncements about any field’s, form’s, genre’s, or medium’s quality becomes, in the end, the sort of cultural claptrap that tempts me to call it kitsch.

Yet I find the recent invitation by Common Reader editors Gerald Early and Ben Fulton to compile a list of the “Ten Best Science-Fiction Novels of the Past Ten Years” irresistible. My repeated objections against the concept of top-ten rankings, after all, never prevent me from fashioning alternative versions in my head whenever these catalogs appear online, in newspapers, or on television. Such, dear reader, is the life of a cultural curmudgeon who doth protest too much. Why not simply surrender to the reality that best-of classifications will never disappear from our critical firmament because they offer us quick and convenient capsule formulations of what we might consider reading before any of the other books languishing in that pile we tell ourselves we will start any day now?

And given how busy we all are, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic recedes, perhaps we should thank these lists (and their makers) for not wasting our time or abusing our goodwill, but instead helping us hack our way through that ever-growing thicket of anime, books, films, podcasts, manga, radio shows, stage plays, television series, video games, and the endless number of other cultural productions we feel honor-bound to track despite this impulse being a forever-frustrated wish that, to switch metaphors, cultural capital’s always-hungry maw ensures will never be satisfied.

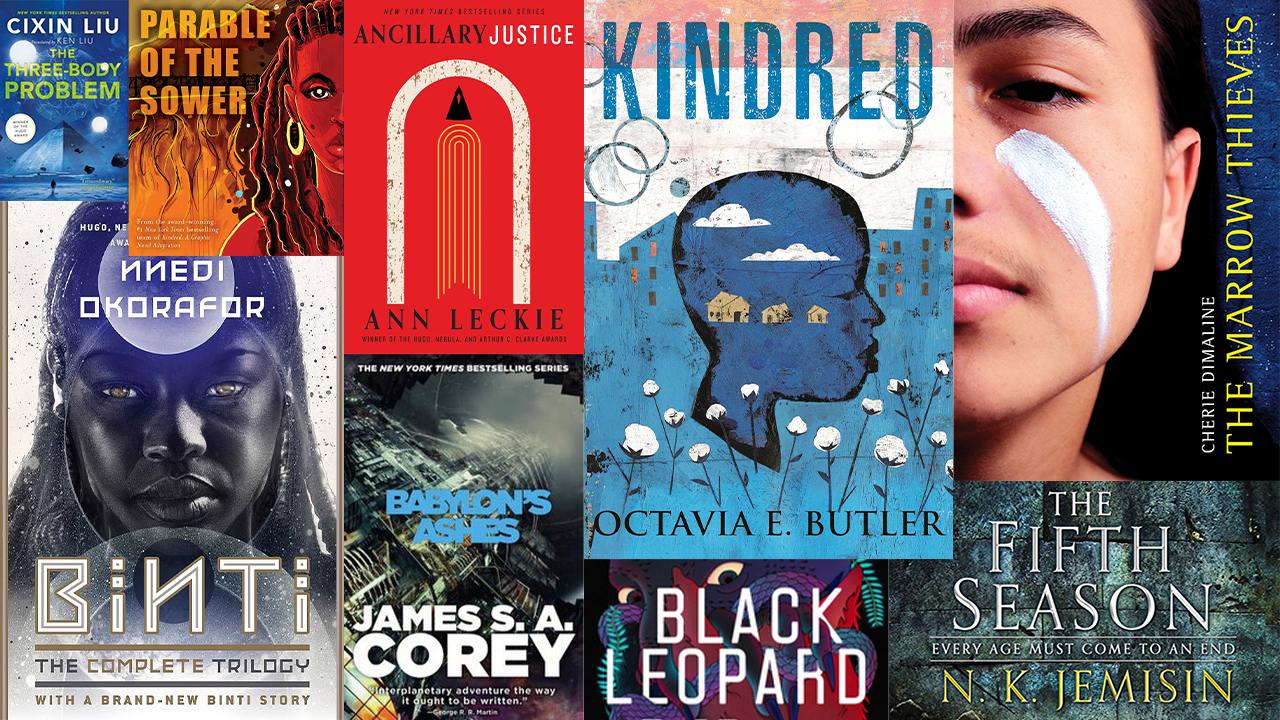

As such, I now honor Gerald and Ben’s request by presenting my anti-list of the “Ten Most-Notable SF Novels of the Past Ten Years.” By anti-list, I mean that the following inventory is the opposite of any definitive ranking, the enemy of any finalized categorization, and the nemesis of any objective taxonomy. By notable, I mean novels (and novellas) that struck me, upon reading and/or re-reading them, as fascinating, moving, provocative, and worthwhile—in other words, terrific work. By science fiction (SF), I mean novels that implicate cultural, economic, historical, religious, and social responses to the scientific advances—whether biological, medical, mechanical, and/or technological—that form such regular (and fundamental) aspects of our daily lives that they are now humdrum, quotidian, and—like wallpaper or carpet—unnoticed unless (and until) we are deprived of them. By the past ten years, I mean books published since 1 January 2013.

So, without further ado, here is my list presented in ascending order. Please construct your own lists or, even better, jump into the “Comments” section (and/or contact me at japaves@yahoo.com) to offer your own rankings, tell me what I missed, scold me for what I excluded, and debate this issue into the wee hours, which is the best outcome that the author of any top-ten list can hope to achieve.

Babylon’s Ashes by James S. A. Corey (pen name for Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck) (Orbit Books, 2016)

Daniel Abraham’s and Ty Franck’s multivolume, multiyear The Expanse book cycle imagines Earth’s future colonization of our solar system as a cultural, economic, religious, and especially political minefield so intricate that it must be read to be appreciated, much less believed. The care with which Abraham and Franck cultivate the tensions arising among the inhabitants of Earth, Mars, and the outer solar system planets, moons, and asteroids being settled by twenty-second-century humanity is as impressive as the way they juggle the enormous cast of characters under their purview.

Babylon’s Ashes continues to spin the central premise of The Expanse’s early novels—that humanity has not yet achieved interstellar travel—in new directions by dramatizing how the discovery of a “Ring Gate” grants humanity access to thousands of extrasolar worlds without needing to travel faster than light to reach them (imagine multiple versions of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s wormhole or the film-and-television-series Stargate’s aperture), which fractures the already-tenuous political ties among Earth and Mars (“the Inners”), “the Belters” (inhabitants of the solar system’s asteroid belt), and “the Outers” (residents of the outermost planets) even more than the first five novels do.

The care with which Abraham and Franck cultivate the tensions arising among the inhabitants of Earth, Mars, and the outer solar system planets, moons, and asteroids being settled by twenty-second-century humanity is as impressive as the way they juggle the enormous cast of characters under their purview.

This tour-de-force effort, moreover, inspired the sixth (and final) season of Mark Fergus’s and Hawk Ostby’s majestic televisual The Expanse, one of the best small-screen SF series ever broadcast. This show not only ran from 2015 to 2022 (the SyFy Channel produced Seasons 1 through 3, then, after canceling the series, sold it to Amazon Prime, which produced Seasons 4 through 6) but also deserves your attention as much as Abraham’s and Franck’s novels (both men served as writers and producers on all six seasons). Their meaty, meticulously imagined, and occasionally pulpy books are renewed pleasures every time you pick them up, with Babylon’s Ashes qualifying as the most-accomplished volume of The Expanse’s nine-novel series (plus nine additional short stories and novellas that share the same setting). Delving into this massive literary cycle will occupy many, many, many happy hours of your time.

The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline (Cormorant Books, 2017)

Cherie Dimaline’s intoxicating 2017 young-adult novel adopts one of those tantalizing premises whose brilliance seems obvious in retrospect. By creating a world in which most human beings lose the capacity to dream, Dimaline takes cues from two José Saramago books—1995’s Blindness (Ensaio sobre a Cegueira) and 2005’s Death with Interruptions (As Intermitências da Morte)—to create a future dystopia where Indigenous people, by retaining this ability, become prey for most other human beings, who go to shocking lengths to obtain the Indigenous bone marrow that helps create a serum that kicks non-dreamers into REM sleep (permitting them to attain the psychological equilibrium that dreaming’s disappearance upsets).

Dimaline holds nothing back in a novel that, while an exemplary experience for younger readers, is a harrowing trip through the terrors, joys, traumas, and beauties of its indigenous characters’ existence, particularly its eleven-year-old protagonist, Frenchie, a boy of Canadian Métis descent. Dimaline does not flinch from braiding Canada’s terrible treatment of its First Nations people into The Marrow Thieves, especially their suffering at the hands of the nation’s residential-school system, better known as the “Indian boarding schools” administered by several different Christian churches whose inhumane policies caused Pope Francis to apologize for the Roman Catholic Church’s role in their maintenance during his July 2022 Canadian sojourn. Despite this noxious history, The Marrow Thieves, in one of its author’s many triumphs, is as much a celebration of indigenous lives as a chronicle of their despair.

Dimaline holds nothing back in a novel that, while an exemplary experience for younger readers, is a harrowing trip through the terrors, joys, traumas, and beauties of its indigenous characters’ existence.

Dimaline’s sequel to The Marrow Thieves—2021’s Hunting by Stars—equals its predecessor’s quality, but The Marrow Thieves, thanks to its precise construction of a world both familiar and estranged, emerges as a consummate SF novel full of cultural, historical, and emotional heft that audiences of all ages will find fascinating.

Infinitum: An Afrofuturist Tale by Tim Fielder (Amistad, 2021)

Tim Fielder’s remarkable graphic novel stretches from those few moments preceding the birth of the universe to those scant seconds after its end to give this tale of the ancient African warlord-king Aja Oba the most epic-imaginable scope. When King Oba’s queen, Lewa, cannot produce an heir, Oba sires a son with his primary concubine, the powerful sorceress Obinrin Aje, but then unwisely separates the baby from his mother so that he and Queen Lewa can raise the boy as their own. Obinrin retaliates by cursing Oba to “see your loved ones wither to dust!”

Thus begins a story stretching through every century of recorded human history into the far future, with the undying Oba witnessing incredible technological advances (some of which he develops himself) that allow humanity to expand across space and time, to discover remarkable new worlds, and to encounter extraterrestrial species with which humankind sometimes goes to war. Fielder unfolds this nimble narrative in fabulously drawn, wonderfully colored, and expertly lettered full-page panels so masterfully realized that each one could hang inside frames on the walls of the world’s best art museums and not seem out of place.

Infinitum does just what its subtitle announces by offering a marvelous Afrofuturist saga whose images, once seen, are indelible. Following the tradition established by Olaf Stapledon’s 1937 epic SF novel Star Maker, to say nothing of the fiction of Octavia E. Butler, Nalo Hopkinson, and Nnedi Okorafor, Infinitum is a career-defining work from one of America’s premiere comics artists.

Parable of the Sower: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by Damian Duffy and John Jennings (based on 1993’s Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler) (Abrams ComicArts, 2020)

Writer Damian Duffy and artist-illustrator John Jennings bring Octavia E. Butler’s brilliantly prescient 1993 dystopian novel to beautiful visual life. Butler’s tale of the United States of America fracturing into an uneasy alliance of competing states, contradictory ideologies, and disconcerted people (who begin embracing fascism after environmental, economic, and political ructions make unity impossible) might have read like a cautionary tale when first published, but now seems like an ahead-of-its-time, crystal-ball-gazing playbook of the past three decades. Butler even imagines a wannabe-authoritarian presidential candidate who adopts the slogan “Make America Great Again” on his path to electoral victory.

Duffy and Jennings smartly adapt Parable of the Sower into a lithe narrative whose visual images range the gamut (from realistic renderings and spooky half-tones to abstract drawings and perceptual paradoxes). Rather than reproducing Butler’s prose verbatim (as does Tony Parker’s massive, word-for-word, 2011 graphic-novel adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), Duffy and Jennings choose to streamline a paragraph here and passage there while retaining all of Butler’s characters, chief among them protagonist Lauren Oya Olamina. This Black teenager, while living in a walled-and-gated Los Angeles neighborhood, conceives an entirely new belief system that she dubs “Earthseed” and that grows in sophistication after homicidal hooligans burn Lauren’s community to the ground, kill most of her family, and force her to escape north with a ragtag group of survivors in search of safer horizons.

Duffy and Jennings smartly adapt Parable of the Sower into a lithe narrative whose visual images range the gamut (from realistic renderings and spooky half-tones to abstract drawings and perceptual paradoxes).

Duffy and Jennings previously adapted Butler’s 1979 masterwork Kindred into a celebrated 2017 graphic novel, but, powerful as this earlier volume is, their Parable of the Sower collaboration is a bracing, colorful, and wonderfully readable companion to Butler’s book. Both men plan to adapt Butler’s 1998 sequel, Parable of the Talents, into graphic form, a happy announcement whose fulfillment cannot come soon enough.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James (Riverhead Books, 2019)

Although frequently classified as a work of fantasy, author and literature professor Marlon James’s 2019 novel so beautifully imagines African cultures, histories, and mythologies as foundational to its story about tensions between “North Kingdom” and “South Kingdom” that Black Leopard, Red Wolf functions as an alternate-history narrative (or, if you prefer, a parallel-world story) as much as the top-to-bottom revision of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings cycle and George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire sequence that many critics have noted. Black Leopard, Red Wolf’s ever-mutating and non-linear structure enfolds so many odd linguistic perambulations that it offers a fabulous—and pleasingly perplexing—few days (or weeks) in the reading chair.

James’s reverence for the Jamaican storytelling rhythms he imbibed growing up in Kingston infuses this novel’s unfolding complexity, especially when a captive character called Tracker misleads his South Kingdom inquisitors with a verbal dexterity that puts The Usual Suspects’ Keyser Söze to shame. Black Leopard, Red Wolf ’s fascination with the past, the supernatural, and the paranormal offers terrific speculative fiction even if purists might claim—wrongly, in my view—that the novel is marginal science fiction. No matter how one classifies it, this book (the first of James’s Dark Star trilogy) is a superbly inventive novel whose sequel—Moon Witch, Spider King—was published in 2022. James is currently writing the third book, tentatively titled White Wing, Dark Star, so snap up Black Leopard, Red Wolf without delay. You will be glad that you did.

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie (Orbit Books, 2013)

Hometown author Ann Leckie’s Hugo Award-winning debut novel, by mixing its many generic influences into a wholly original fiction that grips readers from the first sentence to the final word, astounded me upon encountering it in 2013. This praiseworthy space opera follows Breq, an “ancillary”—meaning a human being whose consciousness is controlled by a shipboard artificial intelligence while serving aboard the Justice of Toren interstellar craft on the colonial front lines of the expanding Radch Empire—i.e., humanity thousands of years in the future—as she seeks revenge against the people who destroyed the Toren nineteen years before the novel begins. Breq, the ship’s sole survivor as well as the only organic being housing its AI personality, begins a quest so full of wonder and imagination that no summary (pun intended) can do it justice.

Nothing beats the pleasure of devouring Ancillary Justice in one or two sittings knowing that its author lives right here among us in St. Louis.

Leckie writes the Radchaai characters as people who do not identify or distinguish one another by gender, exclusively employing the pronoun she throughout this remarkable tale of future humanity’s imperial expansion across the cosmos. Ancillary Justice combines aspects of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish novels (especially 1969’s The Left Hand of Darkness and 1974’s The Dispossessed), elements of Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist and Lilith’s Brood series (particularly 1987’s Dawn), the central premise of numerous cyberpunk novels (especially William Gibson’s 1984 classic Neuromancer and Richard K. Morgan’s 2002 masterpiece Altered Carbon), generous portions of Philip K. Dick’s oeuvre (with 1964’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and 1968’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? leading the way), various features of the Star Trek franchise, and the anarchic energy of Paul W.S. Anderson’s 1997 cinematic creepfest Event Horizon into this fascinating, troubling, and unputdownable mélange that exceeds the sum of its parts.

Leckie’s follow-up novels, 2014’s Ancillary Sword and 2015’s Ancillary Mercy, are such terrific reads that the entire trilogy could occupy this slot—or three separate slots—but nothing beats the pleasure of devouring Ancillary Justice in one or two sittings knowing that its author lives right here among us in St. Louis.

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin (Orbit Books, 2015)

Winner of 2016’s Hugo Award for Best Novel, this first entry in N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy plunges readers into the sociocultural complications of living on a planet that may be future Earth, that has only one continent (known as “the Stillness”), and that every few hundred years experiences a “Fifth Season” of chaotic climate change that provokes all manner of environmental hazards, none more dangerous than the violent earthquakes that plague the Stillness and that threaten the lives of its different communities, castes, and species.

Jemisin, a native of Iowa City, Iowa, has not merely been one of my favorite authors since her inaugural novel (The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms) was published in 2010 but, indeed, one of SF’s leading lights. Both of Broken Earth’s subsequent volumes—2016’s The Obelisk Gate and 2017’s The Stone Sky—won Hugo’s Best Novel award in successive years to net Jemisin a trifecta as deserved as it is unprecedented. The Fifth Season handles its triple-timeline narrative and its three female protagonists as beautifully as any novel, SF or otherwise, that I know, with the character Essun transcending the page to become a living, breathing person so vividly presented that you would not be surprised to enjoy a conversation with her in real life. Jemisin is an extraordinary literary artist, and The Fifth Season is an extraordinary cautionary tale that never surrenders to misery no matter how many cataclysms (environmental and personal) its characters endure.

Binti: The Complete Trilogy by Nnedi Okorafor (Daw Books, 2020)

This omnibus collection of Nnedi Okorafor’s three Binti novellas—2015’s Binti, 2017’s Binti: Home, and 2018’s Binti: The Night Masquerade—interpolates her 2019 short story “Binti: Sacred Fire” between Binti and Home to offer the complete biography of the titular protagonist, a young Himba woman who becomes the first member of her people to gain admission to the intergalactic Oomza University. While traveling there aboard a living interstellar craft, Binti becomes the only survivor of an attack by the Meduse, an extraterrestrial species that resembles large jellyfish and that has been at war with another human group, the Khoush, for decades. These events force Binti to broker a truce with the Meduse by bonding with one of its members, Okwu, and experiencing a profound bodily transformation.

Okorafor models Binti’s Himba heritage upon the actual Indigenous people of southern Angola and northern Namibia, with Binti relying upon otjize, a butterfat-and-ochre mixture that protects her from her home’s desert conditions and that, she later discovers, helps heal Meduse wounds. Binti, who descends from a long line of astrolabe builders, is a mathematical genius whom Okorafor develops in fascinating detail, making Okorafor the foremost inheritor of the late-great Octavia E. Butler’s mantle as our most compelling SF authoress. Okorafor has repeatedly acknowledged this lineage, with her admiration of Butler’s contributions to SF writing and to American literature being matters of frequent public record.

Binti, who descends from a long line of astrolabe builders, is a mathematical genius whom Okorafor develops in fascinating detail, making Okorafor the foremost inheritor of the late-great Octavia E. Butler’s mantle as our most compelling SF authoress.

Okorafor’s four Binti stories so clearly descend from Butler’s Lilith’s Brood trilogy—1987’s Dawn, 1988’s Adulthood Rites, and 1989’s Imago—that they function as extended glosses on Butler’s epic tale of humanity encountering a species of extraterrestrial gene traders that forever alters our bodily makeup and as exquisitely crafted narratives in their own right. Daw Books’ Complete Trilogy reads like the best novel-that-is-not-a-novel (or, perhaps, paste-up novel) in recent memory, so spending a few hours or, at most, a few days with Okorafor’s compulsively readable prose will leave you impressed, rejuvenated, and grateful to have made her acquaintance.

The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin (Translated by Ken Liu, Tor Books, 2014)

Although this first volume in Liu Cixin’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy was published by China’s Chongqing Press in 2008, Ken Liu’s masterful English translation did not become available until 2014. Written by one of the world’s premiere SF practitioners (and one of China’s greatest living authors), The Three-Body Problem tells the most startling alien-invasion story since Robert Potter and H.G. Wells invented this story pattern just as the twentieth century was dawning (Potter’s little-known 1892 novella The Germ Growers and Well’s world-famous 1898 landmark The War of the Worlds being seminal texts in this subgenre). Beginning amidst the Cultural Revolution, this exceptional book tells the story of Ye Wenjie, a prisoner of the Revolution recruited to work for Red Coast, a secret initiative searching for extraterrestrial life.

When Ye, after eight years of constant-yet-unfulfilled work, receives messages from an extraterrestrial pacificist on the planet Trisolaris hoping to prevent its species from invading Earth (yes, shades of Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 stunner Solaris haunt this premise), what might strike readers as a Chinese-set version of Carl Sagan’s 1985 novel Contact (and its 1997 cinematic adaptation) quickly morphs into a complicated tangle of personal, political, and cultural concerns that Liu weaves together with such aplomb, artistry, and audacity that you will want to jump into its two sequel volumes, 2008’s The Dark Forest (2015 English translation by Joel Martinsen) and 2010’s Death’s End (2016 English translation by Ken Liu) as quickly as you can.

Beginning amidst the Cultural Revolution, this exceptional book tells the story of Ye Wenjie, a prisoner of the Revolution recruited to work for Red Coast, a secret initiative searching for extraterrestrial life.

Ken Liu’s translation is so good and so gripping that The Three-Body Problem’s length should not daunt prospective readers, who will find themselves energized after confronting a tome that matches Daniel Abraham’s and Ty Franck’s Expanse novels—goliaths, really—in size, complexity, and fineness. Liu Cixin has won China’s Galaxy Award nine times, with The Three-Body Problem receiving 2015’s Hugo Award for Best Novel, so stop whatever you are doing and rush out to buy this book (unless, of course, you prefer to download its digital version). Either way, you will be enthralled from beginning to end by a bracingly original alien-invasion story that has already produced one Chinese televisual adaptation (released in January 2023) and an English-language adaptation scheduled to debut on Netflix in January 2024.

Kindred by Octavia E. Butler (1979; Beacon Press, Reissue Edition, 2022)

Some readers may feel that I am cheating by listing as my top selection a novel first published in 1979 and written by a woman who passed away in 2006, so to those people I say, “tough times, you poor souls, but please—and kindly—get over it.” Octavia E. Butler, as I have previously written in The Common Reader, was one of twentieth-century America’s greatest authors, while Kindred, as I have previously noted in The Vestibule, is her first undeniable masterpiece.

Butler sets her story of Edana Franklin (“Dana,” for short), a Black woman who aspires to become a full-time writer, in America’s bicentennial year of 1976. On the June day that Dana and her white husband, Kevin, move into their new California home, Dana mysteriously finds herself pulled through time and space to the antebellum plantation of Thomas Weylin, located on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the year 1815. Dana saves Thomas’s young son Rufus from drowning in a river, then returns to 1976 California when the violent Thomas, having never before seen Dana, points a loaded rifle in her face.

This interaction establishes a pattern that sees Dana shuttle back and forth from twentieth-century California to nineteenth-century Maryland whenever Rufus finds his life in danger, forcing her to live for longer and longer periods as an enslaved person on the Weylin plantation. Dana comes to realize that the progressively crude and cruel Rufus will one day father a daughter named Hagar—Dana’s great-great grandmother—with a free Black woman named Alice Greenwood, who lives at the edge of the plantation and is married to an enslaved man named Isaac. After Alice is sold into bondage as punishment for helping Isaac try to escape, Rufus purchases Alice and compels her to become his concubine, making their mixed-raced children, including Hagar, the fruits of forced unions.

Kindred is a gripping, disturbing, and remarkable SF novel that forces its readers to reckon with the grinding oppression of chattel slavery like no other work in the American canon, making it every bit as good as Toni Morrison’s fabulous and haunting Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 magnum opus Beloved.

This précis only hints at Kindred’s complexity, with the novel developing Dana, Kevin, and the Weylin plantation’s enslaved men and women so well that they remain incandescent in one’s memory after even a single reading. Beacon Press’s reissued edition of Kindred coincided with Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s lushly produced, superbly acted, and occasionally problematic FX Network televisual adaptation (canceled after its eight-episode inaugural season dropped in December 2022, although hopes that another network or streaming service will pick up Season 2 remain high).

Butler refused to call Kindred science fiction, instead referring to it as “a grim fantasy”1 because the novel never explains Dana’s jaunts through time and space, but, despite its author’s classification, Kindred is a gripping, disturbing, and remarkable SF novel that forces its readers to reckon with the grinding oppression of chattel slavery like no other work in the American canon, making it every bit as good as Toni Morrison’s fabulous and haunting Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 magnum opus Beloved.

Kindred is not an easy read despite its terrific, elegant, and honed-to-perfection prose, but no other novel I know could occupy this top spot. While my list might include many Butler books, Kindred is an absorbing, stimulating, and finally gorgeous introduction to her work. As SF luminary Harlan Ellison, one of Butler’s early literary mentors, states in his blurb for Kindred, this book “is that rare, magical artifact . . . the novel one returns to, again and again, through the years, to learn, to be humbled, and to be renewed. Do not, I beg of you, deny yourself this singular experience.”2

Kindred truly is that good, that powerful, that incredible, that marvelous, and, finally, that beautiful an experience. As a singular work from a singular genius, it may never be surpassed, in this decade or any other.