The 2016 Academy Awards nominations’ whiteness has become a national civil rights issue. In his opening monologue at the ceremony, host Chris Rock stated: “I’m sure there wasn’t no black nominees [in] ’62 or ’63. And black people did not protest. Why? Because we had real things to protest at the time.” Rock was in error. In fact there were black protests of the Oscars in 1962 and 1963—pickets marched for days in front of the auditorium. As I have previously blogged, Caleb Peterson, a black actor who had felt the sting of the industry’s policy of racial marginalization, organized the protests under the aegis of the Hollywood Race Relations Bureau. And this context helps answer Rock’s question: Why protest this year’s Oscars? The answer is that, in 2016, the confluence of evidence of America’s continued racism is producing a new Civil Rights movement that bears comparison to that of the 1960s. And Hollywood, the self-promoting engine of American pop-culture visibility, has yet to be fully desegregated. This new civil rights activism, though diffuse in locale and without centralized leadership, is discursively united in its zeitgeist. And perhaps more than its 1960s predecessor, it seeks strategically to eradicate elaborately hidden racism, whether expressed through the Academy Awards’ polite, white liberal exclusions, or Ferguson’s brutal racist policing.

In 1962 the Academy responded to Peterson’s protest by increasing the number of black performers on the program, while never condemning the violent police repression of Peterson’s fellow picketers. In 1964, Sidney Poitier won for Best Actor—the first black man to be so honored. Though it would be foolish to suggest simple cause and effect, Peterson’s campaign coincided with other civil rights protests throughout the nation and may have had some influence on an Academy membership that was even whiter than today’s.[i]

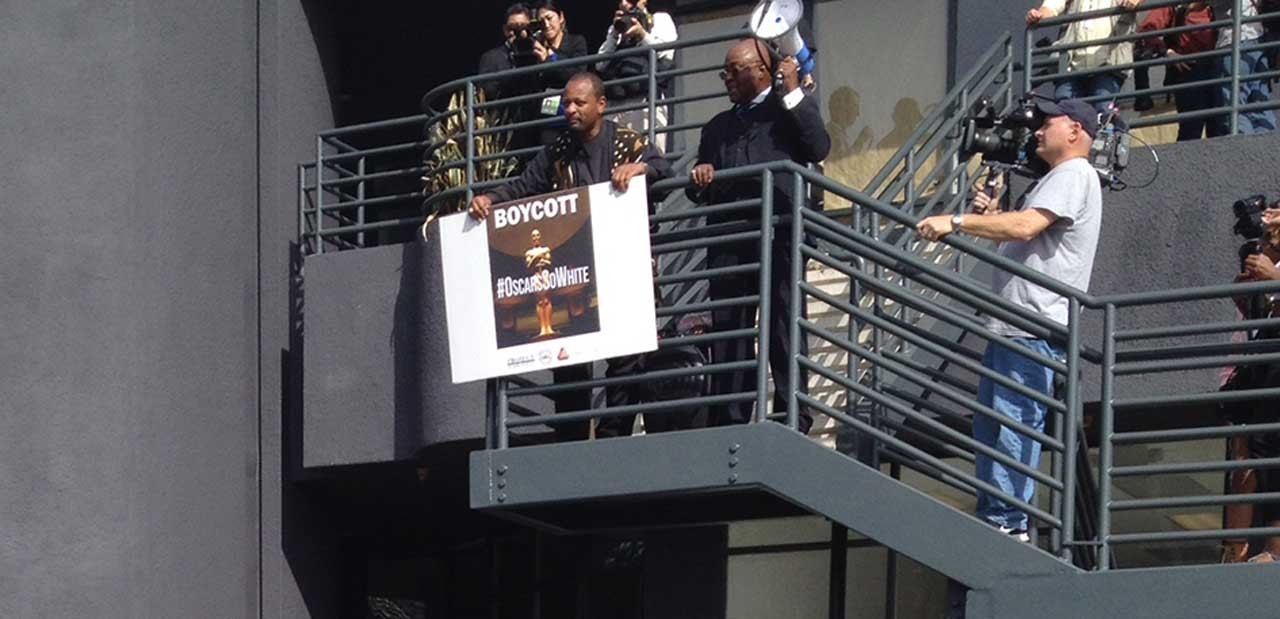

Comparable to the 1960s protests were this year’s tune-out “boycotts” and protests. Before the Oscars, I attended Al Sharpton’s National Action Network protest a few blocks south of the Dolby Theater. Sharpton’s appearance in Hollywood symbolized the links between #OscarsSoWhite and the broader American civil rights tradition. After a “dozens-esque”[ii] litany chiding “Oscar, you so white,” one of the National Action Network speakers repeatedly shamed the Academy for its blindness in recognizing talent of color on the last day of Black History Month, noting that we had too long been sidekicks and buddies onscreen. What impressed me most about Sunday’s protest was the discursive fluidity between #OscarsSoWhite and Black Lives Matter. Several protestors sported Black Lives Matter gear and one woman (who wore an “unarmed civilian” t-shirt) held a sign saying “LA Stands with Flint.” Bringing Flint, Black Lives Matter, and #OscarsSoWhite into the same conversation, helps get us closer to a systematic understanding of how racism works in the 21st century.

What impressed me most about Sunday’s protest was the discursive fluidity between #OscarsSoWhite and Black Lives Matter. Several protestors sported Black Lives Matter gear and one woman (who wore an “unarmed civilian” t-shirt) held a sign saying “LA Stands with Flint.” Bringing Flint, Black Lives Matter, and #OscarsSoWhite into the same conversation, helps get us closer to a systematic understanding of how racism works in the 21st century.

The tenor of the protest was decidedly less grave than its police-raided 1960s counterpart. It combined critique with a kind of celebratory elation that such issues were finally being addressed. Upon Sharpton’s arrival, the tone sobered and the refrain became “no justice, no peace.” Noting that no blacks or Latinos could green-light a movie, Sharpton commented, “no one is saying who must win, but when you have been locked out of the process then you are dealing with a systemic problem of exclusion.” Though Sharpton never threatened violence, as Peterson did in 1963, Sharpton spoke of escalating action and, borrowing Martin Luther King’s phrase, “why we can’t wait”: “Today starts our organizing and escalation to let them know ‘You are out of time … We are not going to allow the Oscars to continue. This will be the last night of an all-white Oscars.’”

The Awards show (which I watched as a commentator) was in many ways crafted in the spirit of protest. For a long time I have secretly resented the Oscars. While recognizing the slick beauty and genuine accomplishments of the nominees and their films, it has always also been a spectacle of unabashed exclusion. Chris Rock and Reginald Hudlin’s Oscars program, as they should justly be called since these men were its auteurs, did much to shift this image. Not only did Rock squarely address race in the openly political tradition of stand-up comedians like Dick Gregory and Richard Pryor, but he never let audiences forget black people—and specifically working-class black people—throughout the course of the show.

Protesters a few blocks south of the Dolby Theater, where the 2016 Academy Awards Ceremony was held Feb. 29.

Rock’s monologue insisted on black presence and contextualized the ceremony in terms of black politics in the age of Black Lives Matter. He addressed not only the Academy’s racial crisis but the history of lynching, civil rights and contemporary police brutality. He did much to reimagine what an awards show can be, transforming it from a celebration of already-vaunted celebrity, to a meditation on “the people”—and specifically the black folk the Academy so often ignores. Chris Rock, himself a smart director and producer, showcased his talent for not only commenting on but theorizing America’s racial politics in his pre-taped and live sequences. His black history minute, starring Angela Bassett, wryly highlighted the ironies of exclusion by focusing on white actor Jack Black rather than black actors or historical figures. But the most powerful element was Rock’s elucidation of the white liberal racist[iii], a concept in desperate need of theorization and cultural criticism.

As he has done in his past turns as host, Rock’s primary address was aimed at the wider audience beyond the auditorium. Not only was his humor raw, satirical and subversive in ways that made the room’s white liberals uncomfortable, but the black viewers in a pre-taped sequence outside a theater in Compton receiving mock Academy Awards upstaged their white counterparts in sincerity, presenting their own arguments for equality.

Chris Rock’s Oscars reboot made me rethink the earlier ceremonies and recognize all that was missing. Previous Oscars suddenly seemed less a celebration of Hollywood talent and more an insular group’s vain, nervous attempt to justify their media domination to the world. The Oscars speech, as a form, routinely shoehorns world politics into a self-promotional spectacle of individual accomplishment. Rock’s comedic brilliance made the Oscars strange to itself and its award-winning constituency. Rock made white liberal actors feel like guests in his house rather than the other way around. As he has done in his past turns as host, Rock’s primary address was aimed at the wider audience beyond the auditorium. Not only was his humor raw, satirical and subversive in ways that made the room’s white liberals uncomfortable, but the black viewers in a pre-taped sequence outside a theater in Compton receiving mock Academy Awards upstaged their white counterparts in sincerity, presenting their own arguments for equality. While Hollywood’s big players may have been laughing at the ignorance of black movie fans, the moment provided a poignant and carnivalesque re-imagination of the balance of class and racial power and showcased the social irrelevance of Hollywood’s prestige projects for the everyday viewer. Only the most racially insensitive or blindly intoxicated member of the night’s auditorium audience could miss that Rock was introducing the Academy members to their real audience. Through this presence of the absent, Rock refused to let Oscar’s problem be reduced to a few elite African-American stars and forced the industry to watch average black moviegoers that he surreptitiously—even radically—brought onto their screens.

Even more exciting was that the surrounding program repeatedly amplified Chris Rock’s message. Academy president Cheryl Boone Isaacs gave an erudite and serious articulation of the Academy’s diversity problem and the planned solution. A brilliant clip from the Governors Award speech of the Academy’s most under-recognized talent, director Spike Lee, provocatively noted that it was easier for a black man to become president of the United States than to head a major studio. And the entire ceremony ended with Public Enemy’s anthemic “Fight the Power,” which epically and epochally connected this ceremony to Lee’s 1989 film, Do The Right Thing. These elements not only made the ceremony “blacker,” as other commentators have noted, but drew smartly and unapologetically on the rich representational history of black cultural production and the civil rights tradition.

Is there something to be critiqued in the Award’s show? Rock’s tone-deaf joke about Asian children being good at math and making cell phones deserves censure. That Rock delivered these lines as the voiceless children wandered confused around the stage visually highlighted the gulf between Rock and the Asian community he was commenting on. Elements like this one speak to a lack of solidarity and intersectional vision that seems to undercut the very idea of diversity that Rock was, at other moments, trying to sanction.

In the wake of Rock’s controversial show came discussion over its low ratings. Some have wielded the ratings in a dubious racial numbers game stacked against the show’s black host and producers, employing the same kind of demographic guess-work that has long kept black actors in the margins because industry execs argue they will not sell in international markets. We can argue about whether the ratings low reflects black protest or white liberal discomfort. But when compared with other less controversial awards shows this year, for better or worse, this low is not significant. More troubling is ABC’s recent announcement that it wants more creative control over the Awards next year. This suggests a relapse on the issue of diversity in the various elements of creative control that is at the center of the protest.

While some commentators complained that race overshadowed the Oscars, that is how protest works. The aim of activism is to disrupt business as usual. Resistance comes by means of disruption of the normal routines and rituals. While it is correct that there are bigger issues in American racial politics than who wins the Oscars, as we enter the era of digital avatars, the politics of representation is increasingly vital and ineluctable—and Chris Rock’s division between “real things to protest” and image-based activism seems increasingly anachronistic. The politics of representation is the real thing.