The Roar of the War For Those Who Could Not Hear It

An account of the impact of the Civil War on deaf culture.

March 29, 2019

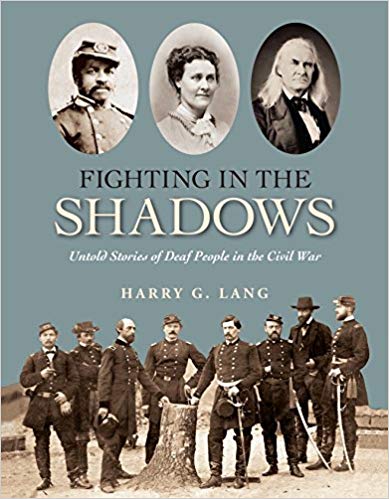

Fighting in the Shadows: Untold Stories of Deaf People in the Civil War

Who knew? Who knew that the designer of the first Confederate national flag was a deaf immigrant from Prussia? Who knew that the deaf poet and journalist Laura Redden was a confidant of both Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth, and that Booth learned sign language to converse with her? Who knew that former General Benjamin F. Butler, champion of schooling for African Americans and head of federal soldiers’ homes, declared that education of the deaf could produce no more than “half a man”?

These are among the vignettes included in Fighting in the Shadows: Untold Stories of Deaf People in the Civil War by Harry G. Lang. The book falls between genres. It is likely not meant as a scholarly monograph—it sustains no distinctive thesis, and illustrations occupy nearly as much space as text—but the use of primary sources and recent scholarship sets the book apart from coffee-table fare.

Studies of deafness in 19th-century America have two key features. Their approach is institutional: historians concentrate on reformers and educators and their philosophies of schooling for deaf children. And they postulate a late-century watershed: prodded by activists such as Alexander Graham Bell, schools for the deaf abandoned sign language in favor of oralism, reliance on lip-reading and speaking aloud. Lang takes no issue with these studies’ findings, but he believes that they undervalue the experience of ordinary people and the convulsion of the Civil War.

The book falls between genres. It is likely not meant as a scholarly monograph—it sustains no distinctive thesis, and illustrations occupy nearly as much space as text—but the use of primary sources and recent scholarship sets the book apart from coffee-table fare.

Lang’s corrective casts a wide net. He has combed published works, manuscripts in archives, and internet sources to yield accounts of hundreds of deaf Americans touched by the war. These stories are Lang’s prize and his burden. They often deliver nuggets equivalent to those about Redden and Butler, but their breadth and interest value limit coherence. Any diligent survey of soldiers and civilians, men and women, Unionists and Confederates, and whites and African Americans creates a mass of detail that can overwhelm a larger meaning.

Lang nonetheless aims for more than a compilation of anecdotes. He proposes the “shadows” of the title as the theme for his stories. The metaphor is an apt descriptor of deaf Americans’ plight. Apart from the minority who attended or taught in residential schools, deaf people were relegated to the fringes of American consciousness, to be seen little and heard less.

But the metaphor is inseparable from its correlates. Taking the remainder of its title into account, Fighting in the Shadows tackles three massive issues—oppression, agency, and war. The difficulty is that Lang’s cast of characters makes no consistent points about these subjects. Edmund Booth and John J. Flournoy are illustrative. Both men recognized discrimination against the deaf, both struggled against it, and both engaged the Civil War’s issues. Here the commonalities end: Booth was an ardent abolitionist and backer of the Union war effort, while Flournoy was a pro-slavery Georgian who supported secession from the Union and advocated a separate commonwealth for deaf Americans.

It might be argued that Booth and Flournoy simply demonstrate the potency of a deaf identity across ideological lines, but the author knows better. Deaf people formed mutual bonds and supportive communities here and there, but most were scattered across a sprawling agricultural society. Booth and Flournoy stand apart in their activism; the majority of their deaf peers fall under Lang’s acknowledgment that “there is no evidence … that deaf civilians had ideological leanings that related to their own enhancement as a social class” (61). The Civil War underscored the point by closing down several organizations and publications for the deaf and shuttering schools in the South.

If the war did little for deaf Americans’ collective consciousness, Lang points out that it offered men and women the chance to prove themselves as autonomous individuals. Motivated by the same patriotism as their neighbors, numerous deaf people sought to join the Northern and Southern war efforts. Some white men who were deaf served in front-line units, typically concealing their condition from superiors and receiving assistance from comrades; others joined militias or filled support roles in the quartermaster or medical corps. Deaf women participated in various ways, from provision of supplies to Laura Redden’s journalism and Susan Talley’s espionage for the Confederacy. Deaf African Americans left even less testimony than did whites, but Lang has found records of deaf black soldiers and instances of deaf African Americans providing intelligence to the Union army.

Most of the accounts in Fighting in the Shadows come from individuals whose deafness predated the Civil War. But the war also produced thousands of veterans who had been deafened by wounds, diseases, or concussions from artillery and small-arms fire.

The narrative of deaf individuals’ contributions implies that they were simply caught up in the Civil War’s larger forces. Lang describes two developments, however, in which the war was the contributor and deaf people the recipient. In 1864, Congress chartered the National Deaf-Mute College, which later became Gallaudet University. The timing might have been coincidence, but Lang cites an observer who declared that the institution was “an outgrowth of the spirit of social justice which came to birth in the pains of the great struggle of 1861-65” (120).

The second development altered the deaf population. Most of the accounts in Fighting in the Shadows come from individuals whose deafness predated the Civil War. But the war also produced thousands of veterans who had been deafened by wounds, diseases, or concussions from artillery and small-arms fire.[1] Lang describes the distinctive challenges of war-connected deafness: deafened adults had limited recourse to sign language, were often forced to abandon their occupations, and faced a heightened risk of accidents. Union army veterans believed that federal pension rates for deafness were too low, and they took collective action. Two ex-soldiers founded the Silent Army of Deaf Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in 1884. The group solicited accounts of hardship from deafened comrades and lobbied Congress for increased pensions. Eventually numbering as many as eight thousand veterans, the Silent Army endorsed sign language and took credit when Congress raised pensions for deafness.

The book engenders a new appreciation for the participation of deaf people in all phases and at all levels of both sides’ war efforts. This is no small accomplishment, but it falls short of establishing the Civil War as a turning point on the struggle over oralism.

Fighting in the Shadows demonstrates the veracity of historian Douglas Baynton’s contention that “disability is everywhere in history, once you begin looking for it.”[2] No one can henceforth dismiss the deaf soldier as an oxymoron. The book engenders a new appreciation for the participation of deaf people in all phases and at all levels of both sides’ war efforts. This is no small accomplishment, but it falls short of establishing the Civil War as a turning point on the struggle over oralism.

The author’s interpretive stance is suspended between idiosyncratic acts and the propulsion of larger forces. The sweeping diversity of Lang’s accounts overshadows any war-connected transformation. For every Edmund Booth, whose support for Union troops evolved into a long career as an activist for the deaf and other causes, there was a Susan Talley, whose postwar writing was a shadow of her antebellum poetry. Against the progress signified by the National College, neglected schools in the postwar South testified to eroding education for the deaf. As the Silent Army embraced the manual alphabet, opponents gathered their forces for the assault on signing.

Fighting in the Shadows brings deaf Americans’ involvement in the Civil War to light. If the author’s interpretations fit uneasily with the lives he sketches, the book remains worth reading for its thoroughgoing revelations.

[1] The most comprehensive analysis of the nature and scale of this hearing loss is Ryan K. Sewell, Chen Song, Nancy M. Bauman, Richard J. H. Smith, and Peter Blanck, “Hearing Loss in Union Army Veterans from 1862 to 1920,” Laryngoscope 114 (2004), 2147-2153.

[2] Douglas C. Baynton, “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History,” in Paul K. Longmore and Lauri Umansky, eds., The New Disability History: American Perspectives (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 52.