The Rise and Fall of The “Empire” of One American University

How a relatively insignificant midwestern university became a player in the Great Game—and lost.

September 30, 2021

“As when a man has ben in pure estat,

And climbeth up, and wexeth fortunat,

And ther abideth in prosperitee;

Swiche thing is gladsom, as it thinketh me,

And of swiche thing were goodly for to telle.”

—Chaucer, “The Knight’s Tale,”

qtd. as an epigraph in The Ordeal of Southern Illinois University

When I was younger, friends insisted that my father, also John, must have been CIA, given the significant time he spent in South Vietnam, Afghanistan, Beirut, and Indonesia, in the 1960s and ‘70s. I did not know if he was with the Agency or not; after I was born in Saigon and we had returned to the States, he left the family and was estranged from me for decades. I had to admit he fit the popular idea of a spook—a fit, hyper-focused, middle-aged White guy with a shaved head; a combat veteran with an education and the tendency to be in one hot spot after another just before they melted down.

“I wasn’t CIA,” he told me, after I tracked him down, in his late 70s, “but I knew some of those guys.”

He valued precision, but in his worldly calm and Midwestern humility he sometimes oversimplified. “I was just a teacher,” he liked to say. This was not strictly true, and he used the same tone when he said, “I met the King of Afghanistan once.”

My father, I have come to believe, was not a CIA Officer, but he was a very American character, not unlike Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, who also started rough, journeyed a long way, and knew how to make things and organize factories. (My dad’s people were from Connecticut too, come to think of it, and before that, in the age of chivalry, from Warwickshire, where Twain starts his story.)

Born the year WWI ended, my father was the son of a sharecropper in Southern Illinois. At the height of the Depression my grandfather had a breakdown after several years of drought, “freakish” heat, failed crops, and no other work. My father helped my grandmother on the farm and was educated in a one-room schoolhouse; as a teen he lived and worked in a CCC man-camp to help the family survive.

My father, I have come to believe, was not a CIA Officer, but he was a very American character, not unlike Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, who also started rough, journeyed a long way, and knew how to make things and organize factories.

He served in WWII with amphibious armored units in Hollandia, Port Moresby, Biak, Halmahera, Leyte, Lingayen Gulf, Borneo and Labuyan; became a tank commander; and was put in charge of seven maintenance shops, 78 medium tanks, and 140 supporting vehicles. He mustered out in 1946, earned a bachelor’s degree in three years, with honors, at University of Illinois, went back in the army reserve for a couple of years (Panama, not Korea), and finished a master’s in industrial education at Illinois in 1955.

That same year, he was hired by Southern Illinois University Carbondale (SIUC) as an instructor of mechanical technology for their Vocational Technical Institute. VTI, as it was called, was a few miles distant from the main campus, housed in the former administration complex of the WWII Illinois Ordnance Plant, hidden in a National Wildlife Refuge.

John’s first half-dozen years at VTI, and his two years in Panama, where he taught industrial arts at Cristobal High School, most fit his claim of being “just a teacher.” But gatekeeping, credentialing, and bureaucracy in that place and time were a fraction of what they are now, and SIUC was an unusual school. Ambition, intelligence, and a love for adventure could take (some) people places.

• • •

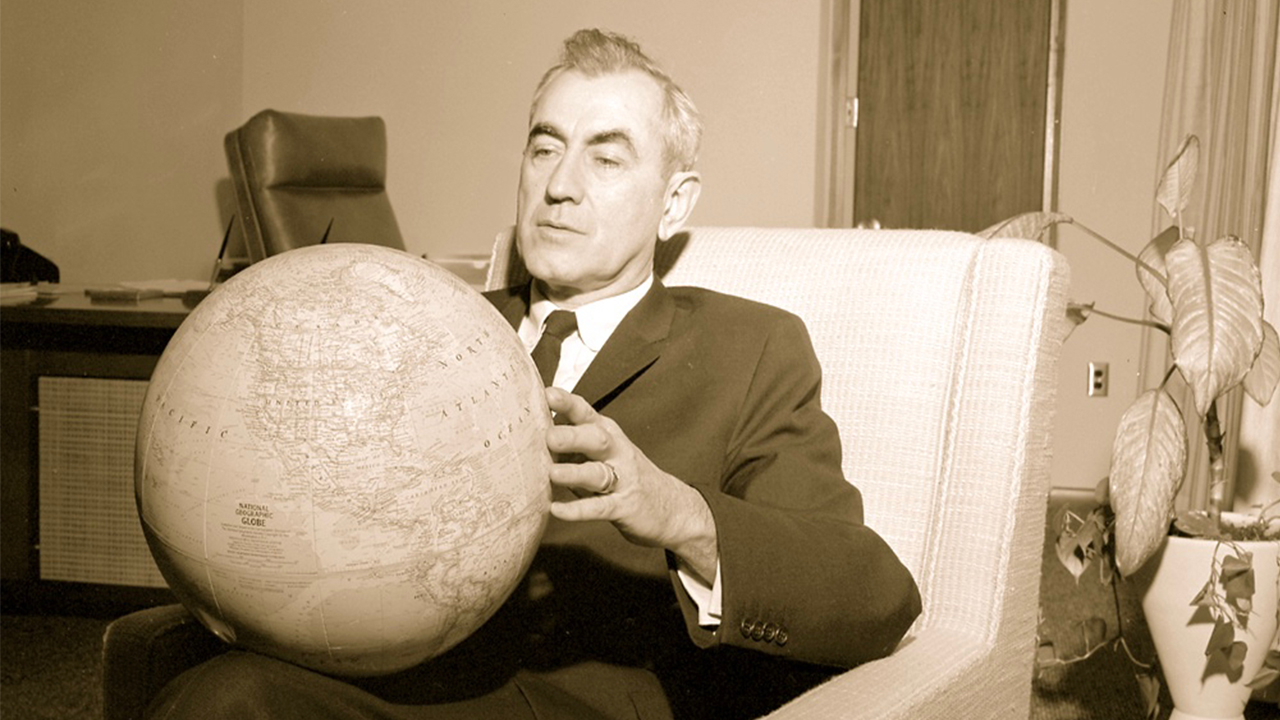

The improbably-named Delyte Morris (1906-1982) was the President of SIU for 22 years, including the period my father worked there. Morris also grew up on a small farm, 100 miles east of St. Louis, but his family got the telegraph concession and other work, and Delyte managed an education and got his PhD. He started work as a high school teacher in Oklahoma but jumped to teaching at University of Maine, then what is now Indiana State, and Ohio State.

He was passed over for president of SIU once but got the call in 1948. People wondered why he wanted the job: Southern Illinois was seen as disadvantaged and backward.

What Southern Illinois was, in part, was colonized. The state of Illinois is tall enough to contain five USDA plant zones, so geographic as well as cultural differences help keep the state’s north and south far apart even today. But Chicago and St. Louis used the coal of Southern Illinois for extractive wealth, as well as for its power plants and foundries, and inevitably dehumanized its residents.

Robert A. Harper, author of The University That Shouldn’t Have Happened, But Did: Southern Illinois University During the Morris Years 1948-1970 (Devil’s Kitchen Press, 1998), got his first teaching job, in 1950, at SIUC, and he was disappointed: “I had never heard of Southern Illinois University,” he writes, despite having gotten his PhD in geography at University of Chicago.

About the time Harper arrived, Carbondale was a railroad town of 10,000, and SIU had been a normal school (a teacher’s college) for 70 years. It had just 3,000 students and eight buildings on its campus.

The state of Illinois is tall enough to contain five USDA plant zones, so geographic as well as cultural differences help keep the state’s north and south far apart even today. But Chicago and St. Louis used the coal of Southern Illinois for extractive wealth, as well as for its power plants and foundries, and inevitably dehumanized its residents.

Over the next two decades Delyte Morris grew SIU to a university with more than 30,000 students; his administration developed schools of agriculture, engineering, law, and medicine, as well as a second campus close to St. Louis.

An article in the Chicago American, February 26, 1959 (qtd. in Delyte Morris of SIU, by Betty Mitchell, SIU Press, 1988) says, “The rapid growth of Southern Illinois University at Carbondale recently has come under heavy criticism from educators, legislators and others. SIU’s leaders have been accused of ’empire building.’”

Morris said, “If some who call us ‘empire-builders’ mean that we are trying through education, to build a regenerated Southern Illinois, then we are empire-builders.”

I spent a day recently looking through the archives at SIUC, and by the letters and other documents it seems as if Morris fought all the powers to create “the second-ranking public comprehensive research university in Illinois.”

But his vision was, in a sense, even larger—almost revolutionary. Morris also hoped to create a new kind of university that would offer a whole-life education in all fields. He had energy, and a belief that there was no separation of campus and community; “the area is the campus,” he said (qtd. in The Ordeal of Southern Illinois University, George Plochmann, SIU Press, 1959).

At a time when others actively worked against his efforts, Morris “created family housing. He lobbied for and got the TV station, the FM radio station, the university press, the news service, and outdoor education [on yet another satellite campus in the woods]. He also promoted ecology, just as he provided facilities for the handicapped years before society demanded them. He brought to the school such [late-career] luminaries as R. Buckminster Fuller, Katherine Dunham and Marjorie Lawrence.”

Robert A. Harper says Morris’s brilliance consisted of “unorthodox practices that in many respects pioneered new dimensions in higher education,” including opening the “doors as widely as possible . . . to the people of [the] economically depressed region, to minorities and the physically handicapped, and to students from throughout the world.”

The astonishing Foreword to Betty Mitchell’s book is by Dick Gregory, who says, “He was not just the head of the university, he was the father. [. . .] Delyte Morris was the first white man I knew who had both power and compassion. [. . .] You see, I had a fantasy about white people—the good: those in the movies (John Wayne, Humphrey Bogart, and Clark Gable) and the bad: the ones I knew in my neighborhood (the policemen, politicians, and ghetto merchants). Although I know now my fantasy was a myth, Delyte Morris was not. He really was the good guy, only he wasn’t reading from a script; the man was real.”

• • •

Robert A. Harper says, “While other schools [especially the University of Illinois, the ‘powerhouse’ of state education] boasted of the academic nature of their curricula, in times before there were community colleges [in the area] SIU offered courses in trades that were needed by the people of its region but were considered inappropriate for an institution of higher education.”

That was VTI, which SIU’s University News Service called the “only university-connected school of its type in the state . . . a two-year college-level technical school that offers training in 29 major fields and options.”

Mitchell reports that in 1964 Morris said, “[M]any people were skeptical about the work when we launched [VTI] 13 or 14 years ago. Educators looked down their noses at us. But in five or six years the situation was reversed. Now the VTI is being held up by educators as an example of what ought to be done in other states. [. . .] A university is like a good library. From the library you draw out a book, but from the university you call out a person who will come to your home town, see your problems with his eyes, and in the light of his special knowledge and his acquaintance with many other areas counsel your community. [. . .] ‘We must take the university to the people.’”

Interestingly, Morris said that the only real resistance to this, by people in the area, was “to a do-good attitude which derives from persons wishing to impose city life upon what is essentially a rural area.”

• • •

It was the age of hearts and minds.

A 1962 report by South Vietnam’s Department of National Education says:

“After nearly a century of foreign domination, Viet Nam has recovered her sovereignty. She is at the same time confronted with several urgent problems that affect her independence. . . . The key problem is to reconstruct the country and improve the underdeveloped economy so as to bring about employment to all. Up until the date of the recovery of independence, we must state that we had neither heavy industry nor light industry. We had to import everything needed for the people’s livelihood, from simple household articles to items of machinery. [. . .]

Under the French period, Indochina had, like other colonies, the role of providing France with raw materials and importing nearly all manufactured products needed for the country. [. . .] In 1955, in all Viet-Nam there were only two technical schools . . . two apprentice schools . . . three applied arts schools, and seven atelier-ecoles. Moreover, several schools were, partly or in whole, requisitioned for other purposes. [. . .] The machines and equipment used for instructional purposes were too old and did not match the progress of our crafts and industries. Besides, there were not enough machines for all the students to use. [. . .]

When the French turned over to the Government of Viet-Nam the technical-vocational schools, there was not a single full-fledged teacher or supervisor of shops of the local service in all the country.”

This sort of idea must have struck Morris hard. Southern Illinois also had its natural resources stripped by outside powers and was left with little political agency. It did, however, have technical and vocational expertise developed in the mining days, the WPA era, and WWII.

Under the flag of the U.S. Overseas Mission (USOM), SIUC sent its first educational team of 13 to Vietnam in 1960. Funding would come soon from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), founded by President Kennedy in 1961. Until USAID, there was no single U.S. agency responsible for all foreign economic development.

(JFK said, “There is no escaping our obligations: our moral obligations as a wise leader and good neighbor in the interdependent community of free nations . . . and our political obligations as the single largest counter to the adversaries of freedom.”

“Isn’t that what we do everywhere?” George Carlin said 10 years later. “We free people and lay a little industry on them.”)

SIU’s website says its “first major international development activity was a $2,106,766 contract from USAID in May, 1961. This project provided pre-service and in-service training for elementary teachers throughout South Vietnam.” The vocational training programs followed.

“Many new schools, such as the National School of Commerce, the Phu-Tho Polytechnic School, and the Vinh-Long, Da-Nang, and Qui-Nhon Technical Schools were founded with funds from national and foreign aid budgets,” the South Vietnamese report says. The number of classes offered jumped from 27 in 1954 to 103 in 1961. Enrollment went from 709 to 3,641.

Robert A. Harper says Morris’s brilliance consisted of “unorthodox practices that in many respects pioneered new dimensions in higher education,” including opening the “doors as widely as possible . . . to the people of [the] economically depressed region, to minorities and the physically handicapped, and to students from throughout the world.”

“During the coming months,” the report says, the Phu-Tho school “will receive additional American equipment valued at 160,000US$. A team of American professors has joined the school to strengthen the instructional program. It is planned that the school will open additional sections to provide training in ceramics, foundry, metallurgy, electronics, home economics, and business education. To help carry out this plan, it is expected that USOM will finance 30,000,000VN$ worth of additional building construction. . . . After this plan is accomplished, technical-vocational education in Viet Nam will have a model technical center, well-housed and equipped with the most up-to-date training equipment in all of South East Asia.”

My father was one of the team at Phu-Tho, as he, my mother, and two half-sisters had left for Vietnam in October 1961. And that is how I got myself born in Saigon, on Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, courtesy of SIUC.

Praise came for the program and for my father’s role in helping build out the school, using his education, military background, and can-do spirit. A report from 1963 indicates he worked with U.S. military officials to get materials and equipment from their surplus yard. A machine-maintenance program was established, the forging and metallurgy shops were relocated, the welding shop was expanded, and a foundry was installed.

“Although the specialist in this area must advise and teach in four areas, he has had five excellent local teacher [sic] as counterparts, therefore many remarkable improvements have been made,” a report in the archive says.

Due to increasing violence in Saigon, my parents’ dissolving marriage, and (probably) scheduled home leave, my family returned to the States in September 1963, a month before South Vietnam President Ngo Dinh Diem (and two months before JFK) was murdered. A travel ban prevented us from returning immediately, and, in the end, none of us ever went back.

SIU’s Vietnam mission continued until 1970. In a letter that year, Fred Armistead, SIUC Campus Coordinator, Vietnam Contract, thanks Morris for making a welcome address at The Seminar for Vietnamese Educators, held on the SIU campus.

“To a majority of the Vietnamese there is only one university,” Armistead said, “and that is SIU (pronounced ‘soo’ by them). In other words, they feel emotionally close to SIU, and I was glad that you were able to come and greet them.”

• • •

After the Vietnam mission was established, Morris used his momentum to build “educational and vocational missions” in “developing countries on three continents,” Over a dozen years, there were programs of various types in Afghanistan, Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mali, Mexico, Nepal, Nigeria, Thailand, Vietnam, and Yugoslavia.

It is startling to look through the archival boxes and see dozens of file folders filled with correspondence pertaining to countries where Morris had involved SIU, was in planning, or had put out feelers. He began to travel more like a statesman, or a traveler for a large firm, than a relatively small university’s president.

My father was one of the team at Phu-Tho, as he, my mother, and two half-sisters had left for Vietnam in October 1961. And that is how I got myself born in Saigon, on Ho Chi Minh’s birthday, courtesy of SIUC.

Morris and his wife took around-the-world trips in at least 1962 and 1963, and another in late 1967 and early 1968. Stops on that trip included Washington, D.C.; San Francisco; Tahiti; Fiji; two weeks in New Zealand; Brisbane; a five-day cruise; Mackay, Australia; Sydney; Tasmania; Melbourne; Jakarta; Bali; Singapore; Kuala Lumpur; Saigon (where he met with Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker and hints at being told that something like the Tet Offensive could happen); Bangkok; Calcutta; Kathmandu; Delhi; Bangalore; Bombay; Karachi; Rawalpindi; Peshwar; Kabul; Beirut; Istanbul; and possibly Belgium.

• • •

After we returned from Saigon in 1963, my father taught at VTI for two years, then became Chief of Party for SIU’s USAID-funded “Afghan Project,” “to render technical advice and assistance to the Royal Government of Afghanistan for the purpose of assisting the Afghan Institute of Technology [AIT] to develop into an effective institution for meeting the ‘middle-man-power needs’ of Afghanistan. . . . ”

John would spend most of the next eight years in and around Kabul, first attached to AIT, then as an advisor to Kabul University and USAID Kabul.

USAID, two SIU news releases say, wanted to “change the orientation of [AIT] from a prep school for engineers to a technical training school for middle managers—foremen, supervisors; and technicians for construction, mining, light manufacturing, and service industries.” There is some confusion between the releases: either University of Wyoming started AIT in 1952, and it was turned over to Afghan faculty until the SIU contract began, or else missionaries started it in a former garment factory.

In 1965 the students lived in a “mud brick, pole and sheet metal building” and could take classes in only four subjects. The five-man SIU team acted as “advisors and ‘counterparts’” to about 45 Afghan faculty, to help develop AIT into a four-year technical high school with 500 students, ranging in age from 17 to 27. The curriculum was changed to allow one exploratory year and three in a major: electricity, aviation, machine tool, building construction, auto-diesel, civil technology, or a general studies unit.

“In 1968 AIT moved into a new $4 million complex of 12 structures [adjoining the Faculty of Engineering at Kabul University] that includes dormitory facilities for 400 students, two classroom buildings, two shop buildings, an administration building, a multi-use cafeteria-auditorium, and two general stores . . . tools, books, laboratory apparatus and other equipment exceed $1 million in value.”

The releases liberally quote my father, who points out that Afghanistan had no railroads, the telephone grid was “being built up,” and there was no television in the country. It had one radio station and a developing industrial economy. The literacy rate overall was three percent, and only 19 percent of eligible youth were in school in or around the capital.

It is startling to look through the archival boxes and see dozens of file folders filled with correspondence pertaining to countries where Morris had involved SIU, was in planning, or had put out feelers. He began to travel more like a statesman, or a traveler for a large firm, than a relatively small university’s president.

“There are very few books in the homes—the country has a tradition of oral teaching—and it is difficult for the students to comprehend written instructions or understand what they read in books without going over the material a number of times,” he says. Most of the students were unfamiliar with technology, and “many of them never even held a screwdriver.” Students who were familiar with aviation and electronics were puzzled by “strange pipes sticking out of the ground on the new campus,” because they had never seen fire hydrants. Hot-water showers and modern toilets were new, and students were paid a stipend to shower once a week to overcome resistance. (By 1970 they complained when water heaters ran out of hot water at peak usage.)

Half the classes were in English, the other half in Pashto or Farsi. Classes ran Saturday to Thursday to accommodate the holy day. All students got government scholarships, as well as food, clothing, and lodging, and all graduates could be expected to be assigned jobs by the Ministry of Planning.

It was a gorgeous country, and no doubt part of the charm for Americans was its difference and roughness. Things were pretty wide-open, and opportunities—as well as competition—lay everywhere. My father says in the article that because Afghanistan kept a “position of strict neutrality in its relations with the outside world,” it received technical and educational assistance from not just the U.S. and the U.N., but also from other nations including Russia, West Germany, France, and Egypt. As a result, from “the standpoint of language and philosophies,” he says, the educational system went “in many directions.”

“The Afghans realize the danger in this,” he says, “and they have begun to turn and try to control some of these differences.” He says “virtually all educational activities in Afghanistan have ‘foreign’ advisors.”

Among them, the article says, are a “large group of Russian advisors . . . previously engaged in road construction, development of gas fields, and city planning, [who are] now building a polytechnic school in Kabul. The Russians also advise and equip the military and a work force similar to the old Civilian Conservation Corps in the US. [. . .] Relations among the foreign groups in Afghanistan are generally cordial, although the Russians do not socialize, Griswold said.”

A March 1967 report on the SIU contract operation says, “From the record and from observations during the visit this program appears to have been developed in a sound and appropriate manner. Relations between the contract personnel and especially the Chief of Party and both USAID and Afghan officials appear to be exceptionally cordial. Mr. Griswold has rapidly achieved a position of status in the American community in Afghanistan and is both liked and respected. This has, no doubt, greatly affected his ability to achieve satisfactory results with the American personnel in other contract programs in Afghanistan and with the USAID officials.”

My father says in the article that because Afghanistan kept a “position of strict neutrality in its relations with the outside world,” it received technical and educational assistance from not just the U.S. and the U.N., but also from other nations including Russia, West Germany, France, and Egypt. As a result, from “the standpoint of language and philosophies,” he says, the educational system went “in many directions.”

The report says AIT was making more formal the possibility that graduated students would go to the Faculty of Engineering at Kabul University. AIT planned to teach more language and science, even as it “sharply increased” the hours in labs and shops, since, as the unsigned author of the report, sounding like Morris, says, “The more narrowly trained the individual is the less flexible he becomes and the less likely it is that he will serve the dynamic and changing needs in the developing country of which he is a citizen.”

Things were looking up for America in Afghanistan. A printed program for the dedication of the new American embassy on July 4, 1967, says, “The new American Embassy building expresses the confidence that the friendly relations that exist today between the United States and Afghanistan will continue to exist tomorrow, and far into the future.” The building cost $1.8 million. U.S. aid to Afghanistan from 1952 to mid-1967 had totaled $400 million.

The dedication program says, “‘Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe,’ H.G. Wells once wrote. For years now the United States and Afghanistan have been cooperating to win that race. Ever since diplomatic relations were established between the two nations, there has been a steady stream of person-to-person exchange.”

The Defense Attaché, and other spooky entities, had their offices in the new building, along with USAID.

• • •

“My dear John,” Delyte Morris wrote to my father, after he got home from his junket at the start of 1968. He sent regrets to the Ambassador and the Director of USAID for missing a dinner in Kabul, but, “We are indeed indebted to you for your many kindnesses. [. . .] It is my hope that [your] suggestions [for funding and expansion] will be accepted by the Afghans and implemented by the United States. [. . .] Best wishes to you. The next time you eat one of those delicious Afghan oranges just remember I am being envious of you.”

Yet, on May 24, Russell McClure, Director of USAID in Kabul, wrote Morris and told him that with their “severely reduced funding level” it was a mark of his respect that he had kept funding for SIU’s Afghan project at “nearly the level originally planned.” He begs to see Morris soon. It was the breeze of sea change.

An article in The Wall Street Journal, January 29, 1969, says there would be “a very rough shake-up” for foreign aid by the Nixon Administration. This came after drastic $1.2 billion cuts by Congress on the previous budget year’s request by LBJ, and an $800 million cut the year before that. “Some reformers” also wanted to merge the “semiautonomous” USAID into the State Department. “The purpose would be to tie aid more tightly to shorter-range US foreign-policy objectives; aid might be withheld from countries that follow economic policies the US believes won’t work.”

“Even worse, some blame aid for dragging the US into foreign troubles. Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman William Fulbright, a former friend of most assistance programs, now suggests they create political alliances that can lead to US military commitments and perhaps even war; in part, he blames aid for getting America involved in Vietnam.”

• • •

Nixon’s announcement on foreign aid was reprinted in The Washington Post, May 29, 1969. “There is a moral quality in this nation that will not permit us to close our eyes to the want in this world, or to remain indifferent when the freedom and security of others are in danger. [. . .] But no single government, no matter how wealthy or well-intentioned, can by itself hope to cope with the challenges of raising the standard of living of two-thirds of the world’s people.”

He planned “to redirect our efforts,” to be more reliant on private enterprise and “multilateral programs,” through international development banks and the UN.

An interoffice memo of October 1969 from SIU’s John Anderson, Dean of International Education, says that the entire team in Afghanistan wanted to continue the program, but Edwin Martin, from USAID, wanted only one person to remain, as an advisor to the school.

“As a result of Dean Simon’s recent visit and evaluation of the program in Afghanistan as well as the information provided by Mr. Griswold, our Chief of Party, we do not feel it would be wise to continue with a one-man operation, Anderson writes.

“The SIU program is highly regarded and has built an excellent reputation in Afghanistan. It is our feeling that to attempt to maintain such a reputation with the presence of only one advisor would be most difficult. More importantly we feel a one-man team could not make a significant input to the solution of problems still existing in Afghanistan.”

Yet Anderson says in a news release, “The objectives of this contract as originally designed will have been largely met by August 31, 1970. [. . .] The objective of preparing the Afghans to run their own institutions has been largely accomplished.”

The building-up of higher education played a role in conservative theologians gaining power, and at Kabul University there was opposition to a BS in Education to create vocational teachers, which was SIU’s last hope to stay in country.

Martin, chief educational adviser in Afghanistan for USAID, says, “This has been one of our most successful programs. Southern Illinois University has provided excellent leadership.”

In a news release my father says, “The project has had very good reports. It has been singled out upon several occasions as a successful operation and an outstanding example of United States-Afghan cooperation.”

An archive of NSA papers shows that King Zahir’s “cautious political and social modernization effort . . . inspired the wrath of Afghanistan’s budding Islamist movement.” In the early 1970s, the United States was tracking a “creeping crisis” in Afghanistan: “lack of quorum in Parliament, university unrest, falling investment, a serious food crisis, and instability among the Pashtuns, that was ‘nearly enough to paralyze the government and probably to frighten the King.’”

The building-up of higher education played a role in conservative theologians gaining power, and at Kabul University there was opposition to a BS in Education to create vocational teachers, which was SIU’s last hope to stay in country. My father and his Afghan counterpart co-authored a study for the program.

In a letter on December 16, 1972, to John Laybourn, associate dean of SIU’s International Education Division, my father said, “The program has been approved by the Ministry of Education and they in turn have requested by official letter that the program be initiated in Kabul University. This however, is where we ran into trouble. [. . .] This is internal University politics. If the Afghans don’t approve soon, then AID will drop the Vocational Teacher Training phase. If this proves to be the trend then I will be finished here sooner than I expected.”

If the program did go through, he says, “I am not interested in Chief of Party.” He would like to do the teacher training program, because he could make a contribution, and it “could be quite pleasant to work without the harassment of the higher level politics and Cocktail circuits. I have done my part of those.” He also believes the advisor to University Central Administration would be the new SIU Chief of Party, and that would be “someone who has had experience in high level University Administration. Also, the PhD will be the first requirement.”

The age of the self-made man, the open season, was over.

“There is snow in Kabul now,” my father writes, sounding melancholy. “This is a bit early but winter is at hand.”

“Ambassador Newmann was not in favor of the project. In fact he would not sign-off on the program and apparently he has now allowed it to pass without his endorsement. It would appear that the Ambassador has lost faith in education as a development tool. The principal problem is strikes and political turmoil in the University.”

Laybourn dismissed my father’s reports and told colleagues in a letter in January 1973 that they should go for not just the vocation technical training part of the contract, but administrative, academic, and research programs too, working with consortia if necessary. (My father was recommended to be the Vocational Teacher Trainer for that portion of the contract.)

“I told [Waffle, the USAID man] that we belong to two consortia,” Laybourn said, “but that we are also quite a comprehensive university. I think we really should go after all we can get. . . .”

At the end of May 1973 my father wrote Laybourn again. “The Vocational-Technical Teacher training program is finally all complete. I have been pushing and politicking with this one for something over a year. This however, is an entirely new concept and no such program has ever existed in Afghanistan. My Afghan friends tell me that the time element wasn’t bad for initiating an entirely new program. [. . .] After three years of draught [sic], Afghanistan has plenty of water this year. They are predicting a surplus of wheat, people seem better satisfied, and things generally look quite good.”

The King was deposed two months later. The Soviet-Afghan War was six years away, in which my father’s good friend and Afghan counterpart was hanged from a streetlamp, he said.

The age of the self-made man, the open season, was over. “There is snow in Kabul now,” my father writes, sounding melancholy. “This is a bit early but winter is at hand.”

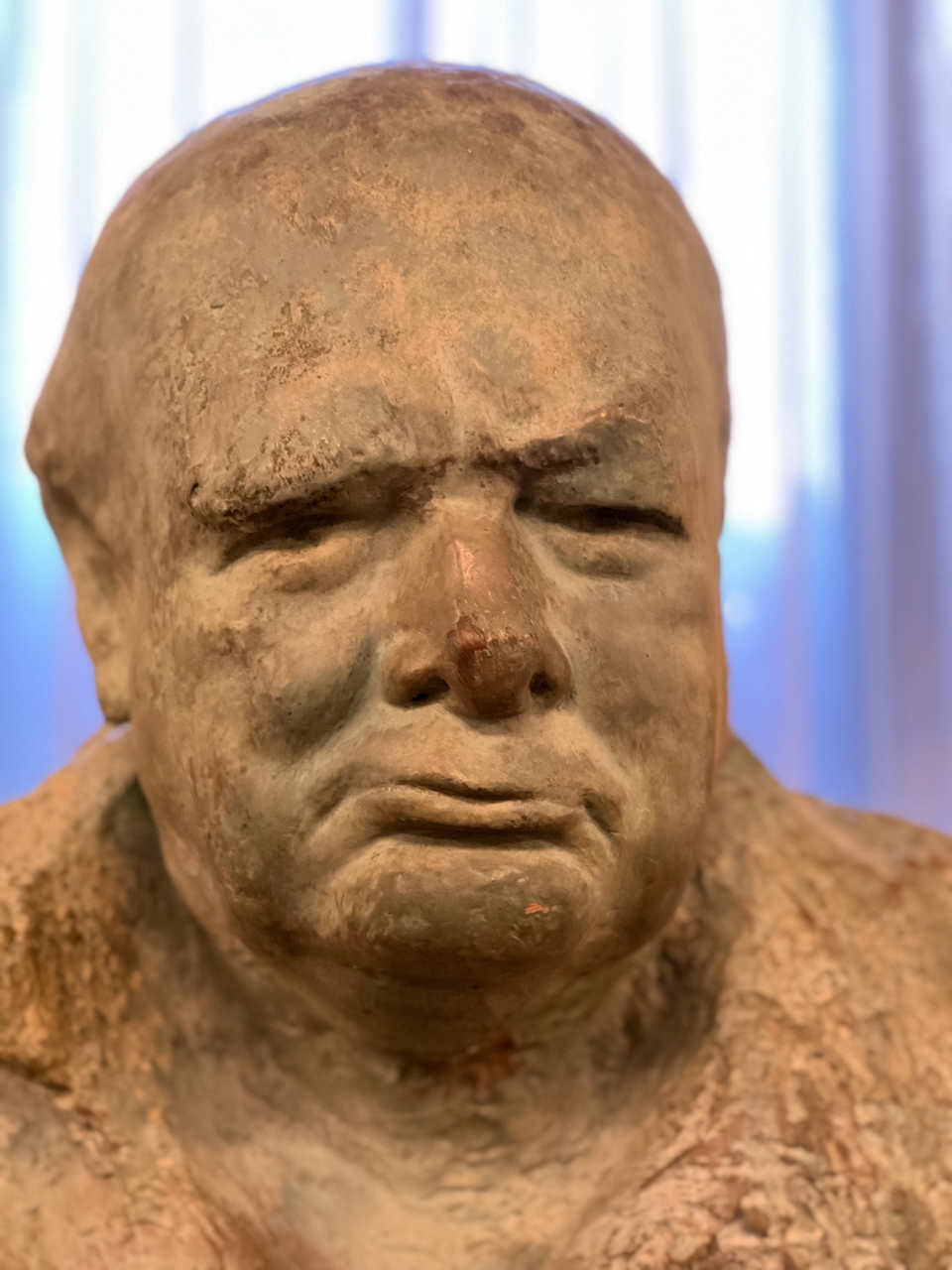

My father would leverage his overseas experience to work as an advisor to the Indonesian tin mines, he said, and served as interim president of Johnson & Wales University. But the rest of his life he remembered Afghanistan and its people, when he did not care to remember or at least talk about Saigon, which is what I was interested in when we met. He loved reading histories about Genghis Khan and liked to carve busts of historical figures from that time and place, all of which looked like himself.

• • •

As early as 1965 there were discussions at SIU about a campus center for Vietnamese studies, building on SIU’s experience in Vietnam. In 1966 the International Studies Division began to “urge” the creation of a Southeast Asian or Vietnamese center, scholar Robert A. Harper says. In March 1969, Morris and the board of trustees approved a Center for Vietnamese Studies and Programs at the Carbondale campus.

“[I]t’s not surprising that [it] would appeal to Delyte Morris’ better instincts,” Harper writes. “Here was a chance for the university to make a significant contribution to the ravaged country whenever peace was achieved. Morris articulated the need for development of those with expertise in the language, culture, and various disciplines needed to assist in the redevelopment of Vietnam when the war was over [won]. Despite how opponents pictured it, the purpose was not to support the war.”

USAID awarded the university a contract for $200,000 per year for five years. Morris was ambitious for the Center, which was to be in “a Vietnamese village” at SIU’s Touch of Nature campus, with “a” Vietnamese educator “as part of the program.” It would instruct Vietnamese students in ESL; create an academic program for Vietnamese language training (and Laotian and Cambodian); offer courses on Vietnam’s culture, history and economics; and establish a journal, library, translation service, a museum, and a “sister-university program with a Vietnamese university.” It would endow a chair of Vietnamese studies; host a conference on the role of American universities in postwar Vietnam; consult with the UN, US government, and other “interested agencies”; train US war vets to serve in postwar Vietnam as “cadre” for development; and allow SIU to take part in lucrative reconstruction.

The Soviet-Afghan War was six years away, in which my father’s good friend and Afghan counterpart was hanged from a streetlamp, he said.

Student protests were growing on many campuses. But the introduction to an article by Douglas Allen, writing in the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, in 1976, says that while anti-war teach-ins began at Michigan, Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard and elsewhere, it was “at places like Kent State, Jackson State, and Southern Illinois University (SIU) at Carbondale, that many of the most bitter and protracted struggles were waged and in many instances crucial victories won. The story of the struggle to defeat the Center for Vietnamese Studies at SIU exemplifies the finest tradition of linking scholarship with real struggle, of unmasking official lies and generating popular widespread support on a critical issue of war and peace. . . . ”

Morris in his early career might now be called a disruptor, but later he wanted to conserve what he had built. His May 15, 1968, letter to parents says “40 institutions of higher education have been affected by disruptive actions of groups of students. . . . Very frequently, the true objectives of the protestors are not clear and often lie outside the institutions. . . . ” He regrets to tell them that after repeated warnings, a small group of students had invaded his office, resulting in “minor” damage and injury; several were arrested and being expelled.

“I am sure that you agree with me that no social institution of the size and complexity of this University can operate without rules and regulations,” he says. “Hence, I feel there is no alternative but to deal directly, firmly, and immediately with individuals or groups who would destroy freedom for all by demanding, by force, special privileges for themselves.”

One of the main campus buildings at SIUC burned to the ground a year later, suspected to be arson. The SDS and other anti-war groups were active on campus (and are described by Harper as calming down angry crowds and picking up trash after protest events). Morris was becoming personally unpopular across the state for pushing hard to spend loads of money on new projects, including a new president’s house, a golf course, and an amphitheater at the campus in Edwardsville.

Morris in his early career might now be called a disruptor, but later he wanted to conserve what he had built. His May 15, 1968, letter to parents says “40 institutions of higher education have been affected by disruptive actions of groups of students. . . . Very frequently, the true objectives of the protestors are not clear and often lie outside the institutions. . . . ”

The president’s house became such a scandal that W. Clement Stone, the positive mental attitude guru and a friend of Morris’s, donated a million dollars to pay it off and take the heat off Morris. Stone, however, was one of Nixon’s biggest private donors, which did not help with perceptions.

In September 1969 the Center for Vietnamese Studies opened, “just as national opposition to the war in Vietnam was escalating on campuses across the country.”

Student protests against the new center came quickly and vigorously, with themes such as, “Off AID, CIA, and Wesley Fishel.” (Harper explains: “Fishel was the focus of a national controversy over his possible connections to the CIA while at Michigan State University and was a consultant to the SIU center.”)

The center received unwanted national attention before it ever got up and running. C. Harvey Gardiner, a research professor of history at SIU, published an attack on the center in local papers that read, “Why should a state university supported by the taxpayers of Illinois have a program that can approximate an academic antechamber to the whorehouses of Saigon? All the pollution in this world is not in air and water; some is in academic circles.” Twenty-five hundred people marched peacefully in the Carbondale streets; the Illinois National Guard was called out. The University of Chicago branch of the National Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars released a petition by fifty-eight of its members that “condemned ‘the threat to academic freedom presented by the (AID-funded)’” center.

Then Kent State happened, and it seems a miracle that the same disaster did not occur at SIU, where students marched by the thousands—some vandalizing property and occupying buildings—and were put to rout by police and National Guardsmen with tear gas. The campus was shut down, classes ended early—my brother-in-law had no finals that year—and as Harper says, “Delyte Morris’ career—and his personal life—largely came to an end at [an] August 1970 meeting of the SIU trustees when he was, for all intents, sacked with little concern for his personal feelings.”

A number of factors led to Morris’s—and the university’s—downfall, including the center, the president’s house, disgruntlement at his “empire building,” financial malfeasance, even perhaps early-onset Alzheimer’s, but most of all, a system so unwieldy that the center could not hold when the man who had held it together for twenty years with his magnetism finally weakened.

The center received unwanted national attention before it ever got up and running. C. Harvey Gardiner, a research professor of history at SIU, published an attack on the center in local papers that read, “Why should a state university supported by the taxpayers of Illinois have a program that can approximate an academic antechamber to the whorehouses of Saigon? All the pollution in this world is not in air and water; some is in academic circles.”

Interestingly, Morris was likened to LBJ, by which his critics may have meant he once did things with progressive promise but turned treacherous. Or maybe they meant his rough, country start in an almost pre-modern world, a world—not very long ago in America—of outhouses and kerosene lanterns; wood or coal heat.

LBJ’s meeting with FDR allowed the Rural Electrification Administration in 1935 “to wire the [Texas] Hill Country and bring power to 2,892 families. ‘I think of all the things I have ever done,’ Johnson reminisced in a 1959 letter, ‘nothing has ever given me as much satisfaction.’” One can imagine Morris feeling the same about the work of the SIU teams.

• • •

Almost immediately, SIU programs began to close or diminish after Morris’s exit. (One of the first to go was the training of Indonesian police at SIU, in February 1971.)

On March 4, 1971, John Anderson, Dean of International Education, and John Olmsted, Dean of the Graduate School, sent SIU Vice President Ruffner and Chancellor Layer a memo that acknowledged how “active” SIU had been in international contract operations over the previous ten years, with support from AID, the Ford Foundation, the Peace Corps, the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, and (preliminarily) with UNESCO. They say many of the operations have been phased out or are being so, due to funding crises; “dissident groups” that “use the war and AID as primary targets”; and “the disruptive tactics employed by these groups . . . being broadened to relate not only to AID sponsored programs but to all others as well.”

They beg administration, in the absence of Morris, for a statement of policy, or “we will find ourselves with a totally different kind of international program than we have had thus far. The University Administrative Council may decide of course that a program devoid of contract involvement is desirable.”

• • •

The rise and subsequent fall of Morris and the university he created is what Robert A. Harper calls “a story of unlikely success and a tragic end.” It does read like an American tragedy, somehow, based in a rustic start, ambition, ingenuity, and the fallibility of good intentions.

Morris gave a speech (reproduced in Plochmann) to consolidated faculty at SIU, before SIU’s adventures abroad began. He ends:

“I do not think I am over-optimistic in believing that Southern Illinois University has within it the seeds of greatness, even though that greatness will be only partly of the same kind as the greatness of Harvard or the rest of the Ivy League or the Big Ten or the major universities of England or the Continent. How will we achieve this? I should say that it will be only by the public, earnest, and repeated asking of difficult questions about education and its place in our society.”

How about: Is there something about western liberal education and technology that leads to inevitable results? Remember how Twain’s Connecticut Yankee ends?

My thanks to Matt Gorzalski, University Archivist, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, and also Stephen Kerber, University Archivist & Special Collections Librarian, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Portions of this essay were published previously at Inside Higher Ed.