The House, and How to Run It

A biographer provides the story of Nancy Pelosi’s deal-making but understates some vital parts.

June 30, 2021

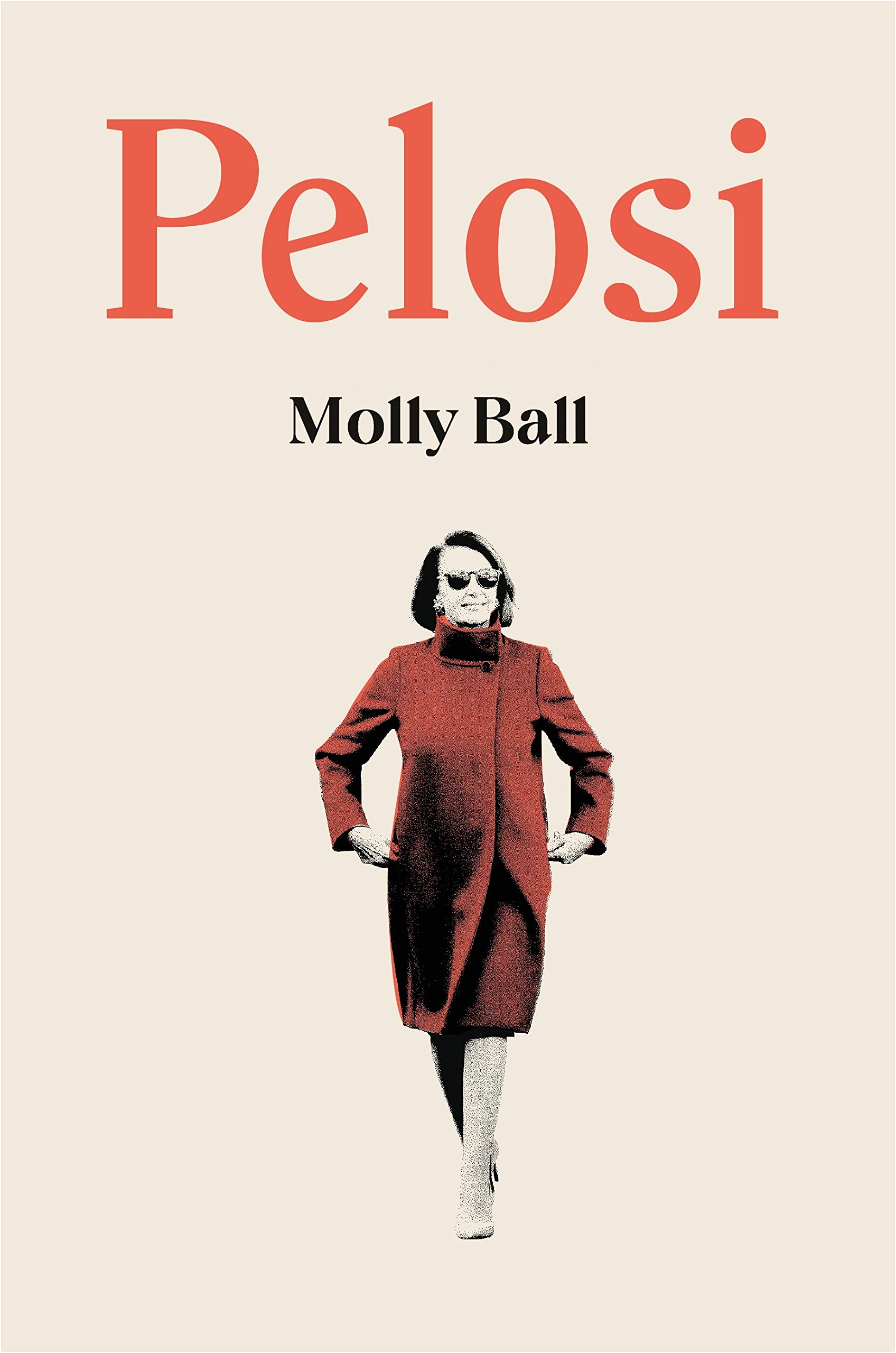

Pelosi

The cover of Molly Ball’s biography of Nancy Pelosi boasts a now-iconic image of the Speaker as she emerged from negotiations at the White House in December 2018. Donning sunglasses and a fire red funnel-neck designer coat, Pelosi carried with her an unmistakably visual swagger and confidence as details of the meeting made their way to the public. Pelosi had just rebuked President Donald Trump when he attempted to explain the difficult position he believed her to be in politically, as she faced a potential challenge to her leadership from within Democratic ranks. “Mr. President,” Pelosi warned him, “please don’t characterize the strength that I bring to this meeting as the leader of the House Democrats, who just won a big victory.” Later in the meeting, Trump said, largely unprovoked, that he would take personal ownership of any government shutdown that might occur due to a failure to reach agreement over funding for a border wall. “I will take the mantle. I will be the one to shut it down. I’m not going to blame you for it,” said Trump. The meeting was widely perceived as a political success for Pelosi and an unforced negotiation error for the president. Later, Ball’s book tells us, Pelosi called Trump’s commitment to the border wall “a manhood thing,” and compared the meeting to “a tinkle contest with a skunk.” (287) In a remarkable observational coda from the most powerful woman in United States politics, Pelosi concluded of the meeting, “I was trying to be the mom.” (287)

The triumphant Pelosi of Ball’s book cover wraps power, politics, fashion, gender, and negotiating success into one package; the picture was so virally popular that Max Mara, the coat’s designer, reissued the eight-year-old coat for sale. There is almost too much to unpack here: Pelosi the master negotiator, Pelosi the grizzled veteran of brass-tack politics, Pelosi the fashionista, Pelosi the mom. When Walt Whitman said “I contain multitudes,” could a better example be found than Nancy Pelosi?

Ball’s portrait of Pelosi’s life in politics is a detailed and exhaustive exploration of Pelosi’s life in politics–an important project that fills a needed gap. But the very nature of the book reveals, first, that the role of gender in negotiation is complex, and Ball’s handling of the issue represents a meta-commentary on the challenge of understanding it. Second, the book helps illuminate that Pelosi’s consistent negotiation success has been achieved not through magic and charisma but through hard work and preparation, an ethos of brass tacks politics that she learned growing up in a political household. And this version of political prowess is not always an exciting or compelling story to the casual eye. Finally, perceptions about hard work, preparation, magic, charisma, and success can itself carry gendered implications for how we understand the work of excellent negotiators and successful leaders.

I. “I Was Trying to Be the Mom”

At eighty-one years old, the first female Speaker of the House of Representatives has led a truly extraordinary life, breaking gender barriers that span more than two centuries. Yet Ball’s biography sidesteps anything more than a superficial discussion of the gender norms and traditionally female roles that largely defined more than half of Pelosi’s lifetime. The years before her children leave her home (she only enters the political arena as they are on the cusp of adulthood) are relegated to a quick summary. In an almost 350 page book, Pelosi’s life in the quarter-century after she graduates from college is covered in a scant twenty-three pages. Those years were not empty of experience; they just did not include the kinds of experiences that Ball determined were worthy of extensive inclusion and dissection.

As a kind of summary of Pelosi’s domestic life, Ball notes, she “was the picture-perfect mother, chaperoning field trips, sewing Halloween costumes and bringing cupcakes to school. But she was also the leader of a fractious team of rivals [her children], responsible for managing shifting coalitions and mediating constant disputes. . . . Being fair to all of them meant making sure each got what they needed–not treating them all the same, but making them feel equally understood.” (13) Ball invites her readers to draw the obvious conclusion, without stating it plainly: this experience would be critical in leading a similarly fractious and dispute-ridden group, years later, in Congress. Ball also notes Pelosi’s increasing involvement in local politics as her children grew older, first as a fundraiser, then as a member of the San Francisco Library Commission, then Democratic National Committee member, then Chair of the California Democratic Party. These experiences were critical in her development as a political strategist. But Ball underplays even these volunteer experiences, as we zip quickly in fourteen pages over her journey from fundraising mom to candidate for elected office.

In an almost 350 page book, Pelosi’s life in the quarter-century after she graduates from college is covered in a scant twenty-three pages. Those years were not empty of experience; they just did not include the kinds of experiences that Ball determined were worthy of extensive inclusion and dissection.

It is reductive to imagine that Pelosi’s role as a mother and a homemaker has defined her political behavior. And yet this reductiveness is a double-edged sword that often defines scholarly and popular discourse around women and negotiation. To avoid an in-depth discussion of how Pelosi’s life as a mother and homemaker–the time that in large part defined her adult life before her election to the House of Representatives at age 47–is to put aside as irrelevant what had to be formative and influential experiences. Pelosi did not emerge fully grown in middle age from the head of Zeus (or, as the case may be here, from the head of her mentor and longtime previous holder of her Congressional seat Philip Burton). Her past experiences did shape her. And perhaps surprisingly, as noted above, Pelosi herself compared her strategy as a leader to her strategy as a mother.

But of course, Pelosi is not “a woman negotiator” who behaves as she does merely because she is a woman and mother. Negotiators are not defined by their gender; there is no one way that women, or men, negotiate. And yet, gender roles can and do influence negotiation behavior and negotiation outcomes.¹ More so than finding that there is one way that women negotiate, research suggests that the stereotypes and reactions that women encounter in negotiation act to influence both behavior and outcome.² The challenge inherent in understanding Pelosi’s life and experience is the same one inherent in thinking more broadly about the role that gender plays in negotiation. And Pelosi herself did not shy away from invoking the role of gender in her negotiations or in her matter-of-fact dissection of the political landscape. Ball describes one contentious meeting at the Trump White House in which Pelosi, being drowned out in discussion, said to the assembled group of men, “Does anybody listen to women when they speak around here?” (256)

Yet Ball puts aside not only an exploration of Pelosi’s adult history in a traditional women’s role, but also most discussion of the way in which Pelosi may have encountered negotiation situations that were complicated by stereotypes about gender. The question of “sexism” is largely left unspoken here, along with the question of how gender stereotypes may have influenced negotiations. Ball resolutely marches onwards without them, highlighting sexism merely as a thing that Pelosi’s “hair-trigger defensive” staff sees “everywhere.” (124) The handful of other mentions of potential gender bias in Pelosi’s career are consistently downplayed here. Pelosi voices a concern, expressed “bitterly,” (231) that sexism animates the failure of Time to put her on its cover when she first served as House speaker, despite appearances by Speaker John Boehner and Senate Leader Mitch McConnell. Ball meets this concern with open skepticism; she calls it a “grudge” that is “petty and conspiratorial.” (316) Yes, Ball herself notes in the book’s Afterword, she eventually “came around” to Pelosi’s view on the cover decision. (317) But can the reader help but wonder if Ball’s reluctance to consider the way that gender may have guided perceptions of Pelosi in the public eye is part and parcel of the way in which Ball approached the topic of Pelosi’s career more generally, largely erasing the influence of her role as homemaker and mother and failing to take a deep dive into the role that gender played throughout her career?

It is reductive to imagine that Pelosi’s role as a mother and a homemaker has defined her political behavior. And yet this reductiveness is a double-edged sword that often defines scholarly and popular discourse around women and negotiation.

Ball raises a serious question about the role of gender only briefly, again in the book’s Afterword, noting that after extensive study of Pelosi for a magazine article, she came to believe that a powerful woman “was defined less by what she had done than by how she made people feel.” (316) She added that many political players had underestimated or underappreciated Pelosi, and that her article aimed to add a narrative presenting Pelosi as a “pioneering woman at a time of unprecedented women’s political activism.” (316) But Ball’s exploration acknowledges Pelosi as a pioneer while never truly interrogating the real effect of gender on her career.

Ball is not alone in this dichotomous approach; research and teaching in the negotiation arena toggle between highlighting the importance of gender.³ and downplaying its significance.⁴ Ball’s account struggles with the line between objectifying and downplaying differences. Pelosi takes the House floor “wearing a blue shirt under a cream-colored pantsuit and her usual four-inch heels.” It is hard to image a male legislator’s clothing being highlighted in this way, yet the reader understands that this detail is meaningful because it captures a part of Pelosi’s identity: the perfectly coiffed and luxuriously dressed San Francisco millionaire housewife turned politician. ⁵ Yet the book, as noted above, does not go deeper into the more inculcated gender norms that shaped women’s lived experience from the time that Pelosi was born in 1940 onwards. A serious and in-depth analysis of this dimension would have added a welcome richness to the tapestry of Pelosi’s life in politics and negotiation.

II. “The Princess” of a Political Family

Another mostly underappreciated dimension of Pelosi’s background in Ball’s biography is her upbringing at the center of a powerful political dynasty. The D’Alesandros of Baltimore dominated local Baltimore and Maryland politics for many years, starting before young Nancy was born. Pelosi’s father, Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., served as mayor of the city and represented his district in the House of Representatives. He made unsuccessful runs for governor and for senator. Politics was the family business: Pelosi’s brother Tommy D’Alesandro III appeared to have assumed the family political mantle and was elected mayor of Baltimore years after his father. But it was, surprisingly, Nancy, with her remarkable facility in navigating complex systems of people and institutions, who truly followed in her father’s footsteps. Indeed, Pelosi’s election in 1987 marked the first time a father and daughter had ever both served in the House of Representatives, and her ultimate political footprint has far exceeded the impression left by her father. Ball documents the massive political operation over which Pelosi’s father nominally presided, also taking care to note that it was Pelosi’s mother who dealt with much of the day-to-day campaigning, fund-raising, and social service provision that being a master of local politics entailed. Pelosi’s mother, known as “Big Nancy,” “knew where all the bodies were buried, and she never forgot anyone who crossed her.” (3)

And so the story of Nancy Pelosi is also the story of an old school politician who grew up steeped in an “all politics is local” culture, where navigating the Housing Authority, the public hospital, or the city courthouse was critical, and making sure that votes were turned out “house by house, street by street, precinct by precinct.” (3) But this cultural heritage feels relegated to a side note in Ball’s accounting; a mere seven pages of the book discuss Pelosi’s childhood. What important insights and lessons might young Nancy, the D’Alesandro “princess,” (5) have learned in these moments, and how did this tradition shape her approach to politics?

Pelosi’s election in 1987 marked the first time a father and daughter had ever both served in the House of Representatives, and her ultimate political footprint has far exceeded the impression left by her father.

Ball tells us early on, without editorial comment, that Pelosi “yearned . . . for a more elegant politics than the grubby, tribal favor-trading practicing by her father.” But the vast remainder of the book that chronicles so much of Pelosi’s work in the House of Representatives paints a different conclusion. Again and again, Pelosi’s negotiating strategy consists of careful vote-counting, clear-eyed assessments of logrolling and trade-offs, and careful cultivation of individuals and relationships and loyalties over time–all what one might imagine she had learned up close in her childhood. At one point, notes Ball, while President Trump, Senator Schumer, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin “bantered, Pelosi was like a broken record. Did they have the votes? If they did, she kept pointing out, they could do whatever they wanted. If they didn’t, they had better negotiate.” (253) Pelosi has used her realpolitik negotiation skills not only in effectuating the Democrats’ legislative agenda but also in fending off multiple challenges to her own leadership within the caucus. But that connection between her political mastery and her family upbringing is a missed opportunity here, rarely noted and never examined in detail.

III. Expert Dynamic Leader, or Overprepared Ungraceful Swan?

These two elements of Pelosi’s past–her pre-politics adult life as a mother and homemaker and her childhood as the beloved daughter at the center of a deeply political family–twist like strands of DNA into the very fabric of her approach to the political world. Her background has clearly guided her as she has worked to negotiate through some of the most thorny and complicated issues in modern U.S. politics. Health care, the war in Iraq, impeachment–all of these were stormy seas that Pelosi navigated, at times more successfully than others, as the leader of the Democratic caucus. And Ball chronicles these negotiations dutifully and diligently. Yet when concluding each segment of these historical events, one is left almost as confounded by how things really happened as when one began.

Oddly, for someone so polarizing, who has occupied as large a place in politics as one might imagine possible for a longtime member of the House of Representatives, Pelosi’s actual work in Congress as portrayed by Ball often feels dry. What is lost in this effort is a sense of Pelosi’s serious craft as an expert negotiator–someone whose incredible attention to detail and work ethic in preparation and leg work is overshadowed by modern personalities. Why is this? Pelosi’s negotiation success is much less glamorous (albeit more successful) than a flashy “Art of the Deal” Trump-style negotiation. Her relentless vote-counting, her steel-eyed horse-trading, her attention to detail and extreme preparedness–these things are not necessarily page-turners. Even Pelosi, Ball says, compares herself to “a swan gliding regally across the water,” who in reality is “paddling its big, black, ungraceful webbed feet furiously underneath.” (193)

What does Pelosi’s success tell us? Negotiation is often not a matter of charm and wit but of details, plans, and ultimately leverage. Pelosi’s exhaustive and exhausting work ethic reveals a fundamental truth that those who teach negotiation circle back to again and again. Serious, focused planning, extensive research–this is how negotiations succeed. Ball’s matter-of-fact narration of the chronology of these negotiations does not fully surface these insights or expose the deep knowledge and strategy that had to take place in order for Pelosi to achieve these results. That seems at least partly because these kinds of behaviors are not often dramatic or “fun” or “sexy.” In negotiation, the cult of personality is often a mirage and a myth; it only achieves transient success.

Although there are flashes here and there of real excitement and insight, the book more often gives a fairly opaque account of the way that complex multi-party negotiations unfolded, with less vivid and personal examples of the way in which Pelosi used negotiation skills such as preparation and persuasion to achieve her aims.

And yet this lesson, too, as seen through the pages of this book, feels deeply rooted in gender roles as well. It is no coincidence that Ball describes the press’s image of Pelosi as a “strict teacher or a demanding mother-in-law,” (157) resonant of Chuck Todd’s famous observation after the 2016 presidential debate, when he described Hillary Clinton as “at times, you could argue, even overprepared.”⁶ This divide between the charismatic male genius and the dogged female plodder is a familiar trope. A 2015 study by a Princeton philosophy professor and her colleagues explored the belief that innate genius and brilliance are male traits, while women are believed to be hard-working and empathic, finding that fields labeled with these so-called “male traits” had significant underrepresentation of women.⁷ In a less scientific context, a man named John Sternal, from an industry group representing car leasing companies, appeared on National Public Radio in 2012 to explain that women were getting better deals on cars because they were doing “more research than men beforehand.”⁸ A female automotive analyst explained, on the same show, “We know that people expect us to fail, to some extent. That people think that we’re not going to know what we’re talking about. So we overprepare, we overcompensate. We don’t go into a dealership to browse. We go in, and we know exactly what we want.” ⁹

Ball offers a similar “due diligence” accounting of Pelosi’s success. Her caucus trusts her because of the work she puts into personal relationships: “[N]ot only did she know every one of her members by name. . . but she knew their history, their district, their ideology, their spouse and kids and parents.” (156) Pelosi “also always had time to listen.” (156) Although there are flashes here and there of real excitement and insight, the book more often gives a fairly opaque account of the way that complex multi-party negotiations unfolded, with less vivid and personal examples of the way in which Pelosi used negotiation skills such as preparation and persuasion to achieve her aims. Pelosi picks up the phone to call every single one of the sixty members of the House who need to be brought on board to pass the Affordable Care Act, but we learn nothing about what happened on those calls.

Lyndon B. Johnson, another keen horsetrader and notorious vote counter, was nicknamed the Master of the Senate;¹⁰ Bill Clinton’s keen ability to connect with people and remember details about their lives was legendary; and Pelosi’s own father was considered a savvy manipulator of the political machine. But Nancy Pelosi is the diligent plodder and planner whose hard work and attention to detail and personal relationships achieve success. Indeed, although she comes around to admiring Pelosi, Ball admits that she initially “didn’t expect to find her particularly compelling.” (317) The dominant narratives that we learn have critical consequences for achievement and for what we model and revere–who we emulate, and who we become.

Author’s note: Many thanks to Susan Appleton and Matt Bodie for feedback and suggestions on an earlier draft of this review.

1 For additional discussion, see Rebecca Hollander-Blumoff, It's Complicated: Reflections on Teaching Negotiation for Women, 62 Wash. U. J. L. & Pol’y 077 (2020).

3 See, e.g., Linda Babcock and Sarah Laschever, Women Don’t Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide (Princeton University Press 2003).

4 See, e.g., Andrea Kupfer Schneider, Negotiating While Female, 70 SMU L. Rev. 695 (2017).

5 Ball herself points out this discrepancy but diminishes it quickly by saying without citation that research disproves the point and that, in any event, “perception and its management are an essential part of politics that shouldn’t be off limits.” Molly Ball, Pelosi (Henry Holt and Company 2020) (124)

6 Chuck Todd, quoted in https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/09/27/what-we-mean-when-we-say-hillary-clinton-overprepared-for-the-debate/.

7 Sarah-Jane Leslie et al., Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions Across Academic Disciplines, 347 Science 262 (2015).

8 Dana Farrington, Women's Car-Shopping Tactics Steer Them Toward Better Deals, NPR Morning Edition, January 27, 2012. www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2012/01/27/145941803/womens-car-shopping-tactics-steer-them-toward-better-deals

9 Id.

10 Robert Caro, The Master of the Senate: The Years of Lyndon Johnson III (Alfred A. Knopf Inc. 1990).