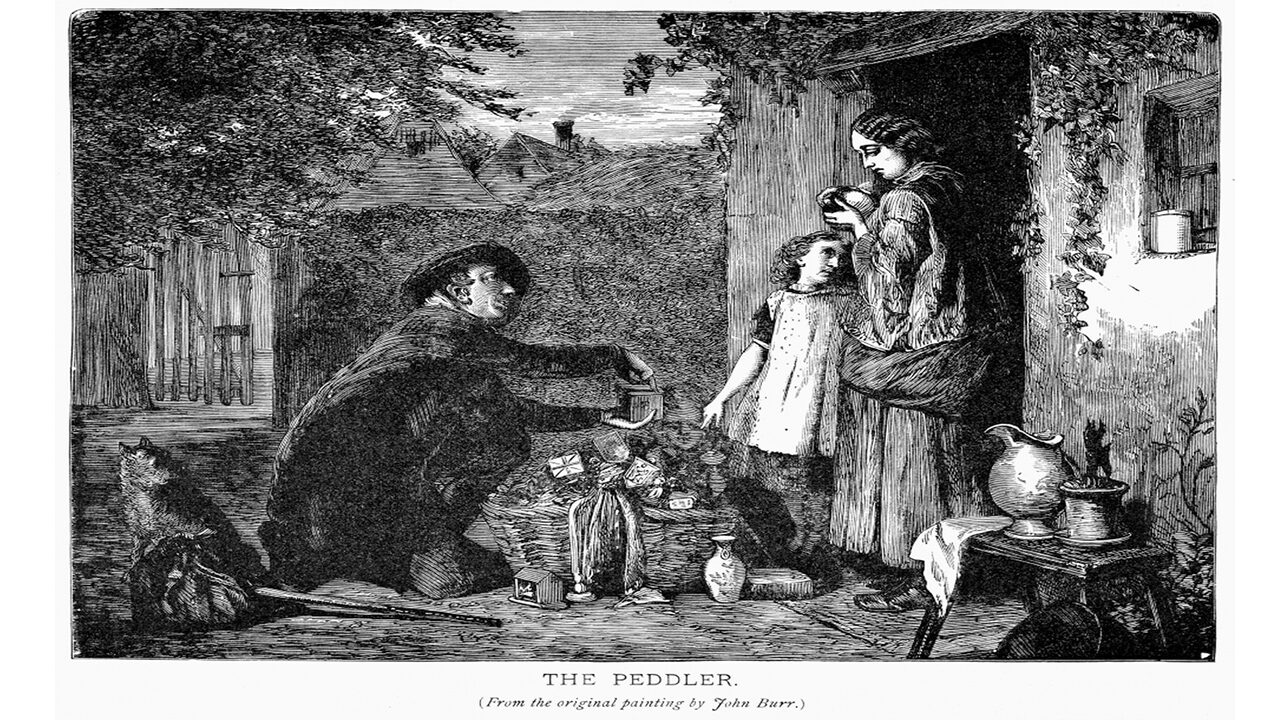

Editor’s note: “The Hair-Pedlar in Devon” by William Clarke was published in 1850 in The Companion to a Cigar. The dialect may be a bit off-putting but the narrative is accessible and clear enough. Here is the story of a wheedling, heartless, hustling hair peddler named Jock Macleod who is trying to buy the hair of young women at a fair in Devon. His tactics seem a combination of seduction, intimidation, ruse, and sales pressure that would make today’s used car salesman seem a rank amateur in comparison. He preys upon young girls with flattery and the temptation of small amounts of money or trinkets. In nearly every case, the girls are remorseful, feeling duped and ashamed, as soon as they sell their hair. Macleod rationalizes his lack of sympathy for his victims by saying that doctors and lawyers feel nothing when they must perform unpleasant tasks in their professions. Macleod gets his comeuppance in the end when he discovers that his daughter was the prey of a rival hair peddler.

The essay provides a vivid sociological picture of how hair was harvested in nineteenth-century England and, indeed, in Europe, much as it is in Asia today. “The hour of bitter distress was the time of his harvest and whenever penury knocked at the door, Jock was sure to follow, if there were any fair females within.” In this way, Macleod resembled an ambulance-chasing lawyer. The women of poor families that needed money to bury a loved one or to put food on the table were especially vulnerable. He disparages a woman who refuses to sell her hair by saying that when she is a goodwife and about to have her second child, she will sell what half of what he had offered. There are more women hair peddlers today than in the nineteenth century, although men still dominate by far and women peddlers are in the same economic position of trying to turn a profit from the hair they obtain, so they are in no less an adversarial position with their clients than the men are. Women are generally more knowledgeable of what their hair may be worth these days to the extent that they know their hair is sought after. Nonetheless, poor women usually sell their hair for small sums because they are not in a strong bargaining position because they are poor. Natural resources must be cheap in order to compensate for the expense of the manufactured commodity for which they are essential.

Although it is not nearly as rich as a literary work, “The Hair-Pedlar in Devon” may be as important an essay in revealing a little-known sub-culture of commerce as William Hazlett’s 1822 essay “The Fight” was in unveiling the underground world of bare-knuckle prizefighting.

The Hair-Pedlar in Devon

On a gay cheerful springtime morning some years ago, I accompanied a brace of the Canns from the neighborhood of Exmoor to one of the chief revels in Devon, whence they hoped to carry off the prize at a great wrestling match. We had scarcely reached the border-booths of the fair, when a few words of wheedling import, spoken with a dulcified North-country twang, irresistibly attracted our attention. Creeping on all fours to the hedge of hazel and white-thorn, from the other side of which the sounds proceeded, we eyed through a convenient gap in boughs and foliage, our old acquaintance, Jock Macleod, the hair-pedlar, with his left palm nestling and warming itself between the grey kerchief and ripe, nuthued locks of a strange lassy from an up-along country. She was evidently unconscious of the wiles and purpose of Jock, and listened with turned head and laughing eye to his discourse. “Ye’re a bonny lass,” quoth Jock, “ye’ve an eye, my maid, that wad tampt a harmit.” “La! how silly you be!” “Eh! lass! and sic a voice—sic a purling, melodious, laverock’s ¹ voice too,—ye’re just a dainty fit for a lords lip—ye are—ye deevil ye—” “Well I’m sure. What must we hear!” “Sic a brow as ye’ve there too! Gude Lord! and the lang silky locks—But wherefore do ye snood them up so, lass? Let ’em fa’l Let ’em·fa’l, woman! Nay, honour! honour! Jock Macleod will na harm ye,—thare!—look for once like a princess,—beautiful!”

The girl with pleased wonder listened to the pedlar, and half assisted, half impeded him in the operation of loosening her tresses, which Jock enfranchised from their silken pink fetters with wonderful dexterity. “There,” resumed he, “now the floodgates are leefted, it flows down about your jimpy waist, which a man may span—just—beautiful to look at! Oh! it’s rare and fair as the siller’s sel’, lassy!” “How you talk!—I’m sure you don’t mean what you say.” “No!—then just to prove and evidence my assertion, I’ll gie you sax gude shillings for it doon upo’ the nail!” “What!” “I’ll gie you sax shillings for the fleece, my wee woman!” “My stars! to be sure, I ha ‘n’t been harkening to one of the hair-pedlars I have heard talk of, all this time?” “Yas, ye have, lass, and wherefore no? tall me that. Will ye say ’greed?” “Get alang wi’ you, do,—you confident oosbert: I could bite my fingers off for being such a fool.”

The girl with pleased wonder listened to the pedlar, and half assisted, half impeded him in the operation of loosening her tresses, which Jock enfranchised from their silken pink fetters with wonderful dexterity.

So saying, the girl twisted up her hair again, and moved off with all possible speed. Jock hallooed after her, “Wall! come! come! I’ll jump t’ither saxpence. What! refuse sax and saxpence? Why, ye devil, do ye understand my words? Sax and saxpence!” The young creature shrieked as much with wrath and vexation as to drown the voice of Jock, and in another moment plunged into a crowd of young men and maidens, who were witnessing the clever tricks in practical philosophy of a gipsy lad. Jock turned upon his heel with a shrug of his shoulder and curl of his hard upper lip, and muttered as he moved towards his pack, “The deevil’s daft—clean gane—she has a saleable ounce of hair or two upon her ugly sconce too, and the fule winna take siller for’t. Well, Jock, my mon! be comforted ye’ll have it for half the day’s offer, when she’s ance a gudewife, and big wi’ the second bairn. Three shillings will purchase comforts, and a lang lock none; besides, the latter’s a grevious matter to kemp ² and keep in order for a matron.” Jock now strode up to another girl much younger than the former, and offered her a shill1ng earnest for her tresses “at eighteen.” The young thing looked alternately at the shilling and a glittering bauble on a jew’s stall of trinkets by her side, and, blushing deeply, snatched at the money, and gave the pedlar her hand upon the bargain. Macleod instantly produced his shears, and reminded her that he must have a token of the purchase on her side, otherwise she might deny it hereafter—not that he thought she would, but there was a regular way of doing business, and order was order, all the world over. The lass silently bowed her head, shivered at the fall of the cold steel on her neck, and the next moment was bereft of full a third of the bright curly tresses which had so long adorned her head. “The wee token,” as Jock phrased it, was instantly hurried into his bag; and one might discover at a glance, by his satisfied leer, that he had taken more than his pennyworth for his penny. The young girl, scarce knowing what she had lost, glided disconsolately away from the bauble she had so lately coveted; and ere she reached the inner skirts of the revel, her shilling fell from her listless fingers. A gip immediately put his broad foot on it, and, after one hasty glance of shame and vexation on the turf, the pretty shorn one ran on, leaving the ’cute swarthy rogue to pick up the prize at his leisure.

But it was not at fairs and revels that Jock Macleod made his best purchases. The hour of bitter distress was the time of his harvest, and whenever penury knocked at the door, Jock was sure to follow, if there were any fair females within. He generally went in with the catch pole, or rent-bailiff, and came out with the corse. “Dead hair,” he would say, “is of no value scarcely, for it will not hold the curl of the frizeur, but I am always glad to lend a helping hand to the distressed!” Often and often has Jock shorn the locks of a village beauty, which, after having been her pride and care from her childhood upwards, she has at length sacrificed, with many a smothered sob and bitter tear, to buy bread for her fatherless child, or some balsam for the body, or comfort in raiment, or food for a sick and bedridden mother! Jock was utterly obdurate on these occasions;—nay, he made his advantages of them, although he had been known to bring a pair of hose, no man could say whence, for an agued pauper, and carried a cotter’s lamb two hours’ march from a ditch, into which it had fallen, to its master’s hearth, when his business lay in an opposite direction. His excuse for want of feeling in hair-pedling was, “Eh! Sirs, it’s wi’ me just as it is wi’ the lawyer and surgeon folk, a professional durity and callousness, begotten by the traffic and occupation we are employed in. A surgeon, who hacks off a man’s leg, and gaes to his dinner wi’ an appetite, wad shiver and shirk from getting out a writ of seizure against a puir soul, that would take the pillow from his sick wife’s head; but a lawyer will do it before his morning sup, and think na mair about it; and yet the same mon wad be quaking, and his humanities wad and vanquish him at the mere sight of an extracted tooth.” It would move Jock almost to tears to hear of a man selling his coat, or an old woman her spectacles, Geneva-bottle,³ or Bible for sustenance; but he deemed it a matter of no moment for a young creature, in the very bud of life, to part with her chief natural ornament for a few shillings to buy her mother a coffin, or save her lesser sister from extremes of hunger and cold. When the cruel stepmother, for a bauble wherewith to bedeck herself, has bartered the fine hair of her daughter-in-law, Jock would look on the struggles of the poor maiden to save herself from the sad bereavement with a smile. He was wily in his bargains beyond credence; and would occasionally cull away the locks of a young maiden, before a definite price was agreed on, and then poizing it in his hand, or throwing it into his copper scales, cast up his eyes, and effect extreme wonder to find it so much less than he expected. He would then handle and part it asunder; pick out a grey or tawny hair or two, and lament that the bulk which, from the sample which had been shown to him, he had deemed worth three half-crowns,—was actually useless.

The hour of bitter distress was the time of his harvest, and whenever penury knocked at the door, Jock was sure to follow, if there were any fair females within.

“But as it’s aff, and partly by my own fault, I’ll gie a trifle, lass, I’ll no be unjust, I’ll gie half the money , though I shall be a sair loser by the deal; but, ah! lass why dinna ye suffer me attentively to examine the web entire afore I cut, then and in sic a case I could ha’ refused; but your modesty your confounded modesty! and your hurryskurry!” The fleece was gone, and the despoiled lambkin glad to receive anything that he offered in return. You might see her colour up as the grey or yellow hair was paraded forth by Jock; and these bargains generally ended in a solitary fit of crying on one side, and a short growling laugh over the cheap prize, under the next lone hedge on the other. Jock was a tall, bony follow, about fifty-five years of age,—his hair was short and scanty,—his brow narrow,—his eye-brows somewhat badgery, and constantly bristled up like the hair on a worried pole-cat’s back. His eye was blue, small, keen, and frosty-looking; but Jock ould thaw it upon occasion into a look of kindness prior to a purchase. After the goods were sold and delivered there was a difference; it then feigned a repentant glance. He would twist about his hard grisled lips, attempt to sigh, and, after expressing a fear that he was going back in the world, take up his polished pack, top on his oilskinned hat, and comforting the female he had shorn with the assurance that the tresses would come thicker and stronger than ever in time, trudge away with all dispatch. “Hair will grow again, if ye clip it ever so dose; but siller ⁴ ance clean gane, is a bird flown,” was an often repeated proverb of the pedlar’s, while driving a deal; and he had always a few gaudy ribbons or lackered glittering ornaments to tempt the witless lass who despised silver. Jock wore a patched tartan coat with black hair buttons for many years; his lower habiliments were equally ancient; but in the matter of vests and kerchiefs Jock was a buck in his way. Scarlet was his favourite colour for a waistcoat; but green plush, and mottled fawn skin were greatly affected by him. His neckerchiefs were of all colours, and he seldom came round without bringing half a dozen quaint or gaudy patterns with him, which he mounted in daily succession, and g’oried in the attention they excited among the homely rustics. Jock’s countenance was rough and weather-beaten; his nose gross, thick and rather downturned at the point; and his chin covered with old razor-scratches, which he attributed to the unrelenting stubbornness of his beard. “Confound the razors,” would he exclaim, “there are none that will cut sax seconds together!” He had a slight limp in his gait, a bend in his shoulders, and usually carried a huge staff, wherewith as well to defend himself and jack as to assist him in his long journeys. Jock, like the swallow, came, no man knew whence, in the sring time, and went, no man knew whither in autumn. The cuckoo was his harbinger, and the first whoop of the winter-owl, the signal of his departure from the western countries. There was a mystery about his visits, that strangely interested the good people of the hamlets. “I ha’ heard the cuckoo athurt ⁵ the harrish⁶ for that vurst time to year!” “Well, Sam, I hope tha disn’t forget to run after un a scaure yards or thereabouts, to pull off thy left shoe, and spit in it for luck’s sake.” “Augh—trust I vor that matter! Odd mun! I spat twice and ran twice; and I’ll lay a groat we do see Jock Macleod’s pack within a week.”

There was a mystery about his visits, that strangely interested the good people of the hamlets.

Jock came within the time prophesied; but it was his final visit. He had left a female child, who was supposed to be his daughter, at this same dame’s house, fourteen years before, and paid regularly for Patty’s provision and keeping at the hinder end of every autumn. She was a plain lass, but her hair was beautiful; and Jock admonished her yearly, to cultivate its growth, and to regard it as the second personal honour of a woman. A few days before his last visit, Bandy Scrimshire, a rival pedlar, in a minor way to Jock, had purchased Pat’s woof of jet-black hair for a bottle of sweet scented waters, a peach-blossom kerchief, two pieces of pretty crooked money ( old underfaced shillings) and a worsted purse to put them in. Jock’s wrath at finding his child boyheaded, it would be impossible to describe. He emptied the sweet waters slowly and solemnly into a cesspool; threatened to hang the girl in the peach kerchief, burnt the purse; and thrust the pretty money into the innermost nook of his leathern pocket. The keen reproaches and bitter arguments of Jock against his daughter’s most heinous offence, soon got abroad, and greatly impeded him in his subsequent gathering for the year. Bandy Scrimshire also noised a story abroad, that he had met Jock on his way to visit Patty, and actually vended the woof to Jock himself at an extravagant price,—the latter having taken so manifest and unaccountable a predilection to possess it, that Bandy found it easy to inveigle him out of twice its actual worth. Little did Macleod imagine that he was purchasing the growth of his “ain flesh and blood;” but have it he would at any price, and Scrimshire sold it to him dearly. Jock was jibed on this score so sorely, that, in the ensuing autumn, he put Patty upon a yearling donkey, and left the West for ever, anathematizing it as he went away, as a beggarly, upstart land, where the kite fattened, and the honest bird was plucked of his last breast-feather. “The malediction of an upright man dog it eternally,” quoth Jock,—and off he trudged for ever.