The Fat, the Thin, and the Psychology of the Body

A writer looks at recent books on women, fatness, and fasting.

By Emily Gordon

September 28, 2020

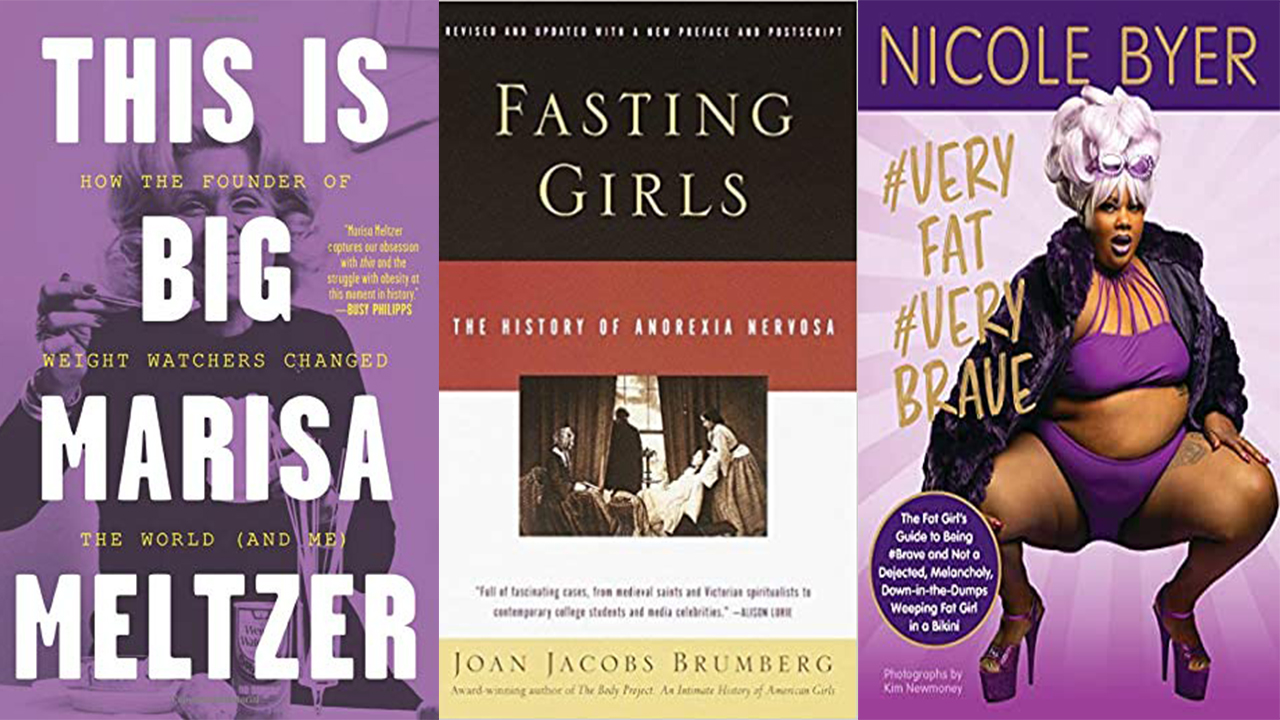

• #VERYFAT #VERYBRAVE: The Fat Girl’s Guide to Being #Brave and Not a Dejected, Melancholy, Down-in-the-Dumps Weeping Fat Girl in a Bikini

By Nicole Byer

(2020, Andrews McMeel) 181 pages, with photographs and illustrations

• This Is Big: How the Founder of Weight Watchers Changed the World—and Me

By Marisa Meltzer

(2020, Little, Brown and Company) 304 pages

• Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa

By Joan Jacobs Brumberg

(2000, Vintage) 374 pages, with endnotes, index, photographs, and illustrations

“Just try to explain to anyone the art of fasting! Anyone who has no feeling for it cannot be made to understand it.”

—Franz Kafka, “A Hunger Artist”

I type this hungry. I am what is known as a “small fat”; I can buy clothes at the far end of the “straight size” spectrum, and benefit from the privilege that affords me. Still, on dating sites, I see “No BBWs” and understand they are talking about—rejecting—me. (BBW stands for “big beautiful woman”: fat.) I am familiar with these terms because for a number of years, I have immersed myself in the language and imagery of body positivity (BP), fat acceptance (FA), health at every size (HAES), and other movements that confront stereotypes of obesity and embrace bigness as a human fact, a human right, and a source of beauty, glamour, and power.

There is a rich reading list for enlightenment on this front, including Kate Harding and Marianne Kirby’s Lessons from the Fat-o-sphere: Quit Dieting and Declare a Truce with Your Body (2009); Roxane Gay’s Hunger (2017); Kelsey Miller’s Big Girl: How I Gave Up Dieting and Got a Life (2016); Jes Baker’s Things No One Will Tell Fat Girls: A Handbook for Unapologetic Living (2015); Sabrina Strings’s Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia (2019); Virgie Tovar’s You Have the Right to Remain Fat (2018); Sonya Renee Taylor’s The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love (2018); and Lindy West’s Shrill: Notes from a Loud Woman (2016), among many others.

The radical and welcome change in my media diet led me to Nicole Byer, a comedian, podcaster, and recreational pole-dancer. Byer makes it clear in her book’s title that she is navigating a specific internet territory studded with irony and hashtags: #VERYFAT #VERYBRAVE: The Fat Girl’s Guide to Being #Brave and Not a Dejected, Melancholy, Down-in-the-Dumps Weeping Fat Girl in a Bikini. As she explains, she had been posting bikini photos of herself on Instagram when a friend convinced her to collect them in a book. The resulting collection, with photos by Kim Newmoney, is part glossy coffee-table book, part manifesto. She immediately throws euphemism out the window: “I wanted to write a book about fat ladies—because I am one. Not curvy, not plus-size, not big-boned, not fluffy, not phat. I’m FAT. I am a fat lady who loves wearing bikinis. Which is #verybrave in our culture today.”

… for a number of years, I have immersed myself in the language and imagery of body positivity (BP), fat acceptance (FA), health at every size (HAES), and other movements that confront stereotypes of obesity and embrace bigness as a human fact, a human right, and a source of beauty, glamour, and power.

While Byer spends some time telling the story of her evolving relationship with her body—one FA proponents will recognize—she gives the majority of her book to Newmoney’s photos, all Southern Californian sun-baked walls, rich textures, desert plants, and color blocks. She captions each photo with a wry, self-aware text. On her pose in a tangerine two-piece on the intricate tiles of a hot tub, she writes: “Wow, this is real #bravery. What if my big, banging bod smashed all this tile, and the hot tub collapsed, and I crashed through the pool all the way through the layers of the earth, to the earth’s core, and then I melted … slowly, because I have so much body. That’s a lot of what-ifs. Truly so #brave to take that on. I commend myself.”

She also has some practical advice for fellow fats, including how to mix and match tops and bottoms to make the most of a less sumptuous bikini collection. But mostly, the images themselves are the how-to. Byer has, as they say, processed a lot of information about being female, fat, Black, sexy, and funny, and produced a joyful book: a personal celebration that is also a permission slip for readers to feel good about both her body and bodies in general.

I leave it to social historians to draw comparisons with other identity movements, but it can be hard to bridge the gap between accepting fatness in others and accepting it in yourself—and waiting for the rest of the world to catch up. My own trajectory: I was a solid but (clumsily) athletic child, teenager, and young adult who believed, incorrectly, that she was unhealthily overweight. Fatphobia was everywhere, in magazines and movies, from teachers and peers. “A moment on the lips, forever on the hips.” “Nothing tastes as good as being thin feels.” “Lose weight now—ask me how!”

Starving is also romantic, especially for artists. The heroes of New Grub Street, Victor/Victoria, La bohème, The Gold Rush, The World of Apu, and indeed Knut Hamsun’s novel Hunger are among the scores who suffer scrawnily. Who deserves a hot currant bun more than pitiful Sara in A Little Princess, or the poor children in Max Fleischer’s 1936 cartoon “I’ll See You Somewhere in Dreamland,” covered in tattered blankets and longing for candy? Kafka’s “hunger artist” is a sad spectacle—the circus crowds are bored with public starvation—but his dedication to his art form is complete.

While Byer spends some time telling the story of her evolving relationship with her body—one FA proponents will recognize—she gives the majority of her book to Newmoney’s photos, all Southern Californian sun-baked walls, rich textures, desert plants, and color blocks.

I spent my late twenties and early thirties as an obsessive amateur dancer in the Lindy Hop scene, probably as skinny as I will ever be, doing the Charleston in ’30s satin gowns. By my late thirties, a job loss, fertility treatment, two failed pregnancies, and depression had taken their toll: I was fat. A short-term boyfriend once grabbed one of my thighs and said, “This could feed a whole village.” Another man, a graphic novelist, told me my body was perfect (I did not believe him) but only drew Edwardian sylphs. Indignities abounded; I stopped identifying with myself, started dressing to hide, stopped dating. Paul Simon’s whine was now mine: “Why am I soft in the middle now / When the rest of my life is so hard?”

Twice since then, I have lost fifty pounds on Weight Watchers, both times to showers of outside approval. “You’re half of yourself!” exclaimed one friend, meaning it as praise. I felt famous. Courtney Love on her past: “I was fat, and when you’re fat you can’t call the shots. It’s not you with the power.” One guess as to what happened next. There is a New Yorker cartoon by Robert Leighton titled “Your Lost Weight,” in which one avocado-shaped lump asks another, “Ready to head back?” Thanks a lot, lumps! Still, I learned to lump it. Once I started surrounding myself with better words and pictures—and stopped resisting them with my own fatphobia—I found myself modeling for painters and photographers, buying cuter clothes, and generally getting #braver.

Recently, I got tired of my knees hurting as I climbed my three-floor walkup and felt a cold dread from reports of my increased susceptibility to COVID-19. Proudly fat celebrities who have recently lost weight include Gabourey Sidibe, Roxane Gay, Rebel Wilson, and Adele. Body-positive, though, we all return to this haunted house with ambivalence. My current bio on WW (as the company has rebranded itself) reads: “I’ve done it before and I’ll do it again!” This seems fatalistic, but what is a better self-description? “Statistically, I’m unlikely to keep this off, but I’m sure I’ll beat the odds!”

Marisa Meltzer, an accomplished magazine journalist, knows the numbers well. She comes to her book This Is Big—part memoir and part biography of Weight Watchers founder Jean Nidetch—well versed in body-positivity rhetoric, feminist critique, and a lifelong experience with weight self-consciousness. She, too, has been thin; she has also suffered badly, both physically and psychologically, for that elusive thinness.

Nidetch’s rise from obscurity to fame is so picture-perfect that it is remarkable that her name is not cited among the greats of twentieth-century business success.

Like Julie Powell’s similarly hybrid book Julie and Julia (2005), This Is Big is simultaneously entertaining and poignant. Meltzer alternates between telling Nidetch’s story and relating her attempt to give Weight Watchers a try for a year, despite the fact that “I had long dismissed Weight Watchers as the most retro, basic, lowest-common-denominator, least chic diet company in the world.” In the process, she exposes some of the pretzel logic of weight-loss and “wellness” culture and examines her own identity as a plus-size person who often covers the world of body-crazed celebrities. Meltzer faces a greater challenge than cooking like Julia Child: undoing her destructive early conditioning and trying to become, in effect, not just a thinner person but a different one.

Nidetch’s rise from obscurity to fame is so picture-perfect that it is remarkable that her name is not cited among the greats of twentieth-century business success. Once an overweight Queens housewife, she lost twenty pounds through a bare-bones city program. Gifted with the ability to get people talking, she founded a group where women could open up about their weight with humor and without shame. By 1963, it had become the ambitiously and prophetically named Weight Watchers International. A born charmer (“she would have been a wonderful talk-show host,” Meltzer writes), she became a swinging celebrity, dated Fred Astaire, and made an empire out of her once-modest meetups. After selling the company, amid rapid changes in the landscape of wellness, food and fitness trends, she faded from public view and died at age ninety-one.

Taken as a whole, This Is Big is an important document of twentieth- and early twenty-first-century culture with a strong voice and feminist lens. Meltzer’s large scope is admirable, but her personal history is less assured than her journalistic and historical accounts. This is understandable; as she writes, “I regret the money and effort I’ve spent on dieting. I wish I could restore what I have taken from myself. But at the same time, I don’t fully accept body positivity, which presumes one is living in a vacuum and also doesn’t acknowledge the reality of living in a fat body.” Nidetch was ever-vigilant to preserve her weight loss (her identity as well as her brand), but Meltzer lives in a less binary world and bravely—I think Byer would agree with the term—reveals herself as a reluctant member of both dietland and fat acceptance. Still, the book documents more than one courageous path; Meltzer is not, in fact, the same person at the end of the book.

Since, like Weight Watchers members everywhere, I spend at least part of each day wishing I had more food, I dove into the self-punishing abyss with Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa, by Joan Jacobs Brumberg. Her book, written in compressed but not jargon-laden prose, describes female fasters through the millennia. “Women who were reputed to live without eating—that is, without eating anything except the eucharist—were particularly numerous in the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, a time when food practices were central to Christian identity,” Brumberg writes. “By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, scientifically-minded physicians began to pay close attention to food abstinence, so common among women of the High Middle Ages. They called it both inedia prodigiosa (a great starvation) and anorexia mirabilis (miraculously inspired loss of appetite).” Brumberg tracks the progress of these related conditions “from sainthood to patienthood,” from the hungry but productive labors of medieval saints to modern-day hospital wards of gaunt teenagers in thrall to sticklike idols.

In between, she tells the particularly riveting stories of the title’s “fasting girls” like Martha Taylor, Ann Moore, Sarah Jacob, and Mollie Fancher, abstemious young Anglo-American women in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries who became spectacles in their small communities. Like the hunger artist in his circus cage, they spent their days in bed, specters of their former selves, while their parents showcased them to gawkers. Claiming not to eat for months or years, they eventually attracted skeptical doctors, whose round-the-clock watches sometimes resulted in the weak girl’s death.

Taken as a whole, This Is Big is an important document of twentieth- and early twenty-first-century culture with a strong voice and feminist lens. Meltzer’s large scope is admirable, but her personal history is less assured than her journalistic and historical accounts.

“In the early modern period … one fasting girl allegedly ‘din’d on a rose and supt on a tulip; another took only aqua vita as a mouthwash; and still another was said to live by her olfactory sense, inhaling only the ‘smell of a rose.’ The symbolic diet of the maiden underscored her purity.” In the seventeenth century, writes Brumberg, some believed Taylor “was fed by angels, fairies, or benign spirits” that kept her alive. A contemporary (1811) theory had it that Moore “lived on elements in the atmosphere—specifically hydrogen, which she drew from air and water.” Puritan exemplar Cotton Mather dismissed theories of fairies and concluded that “long fasting is not only tolerable, but strangely agreeable to such as something more than ordinary to do with the Invisible World,” that of Satan. Brumberg adds: “In passing, Mather observed that ‘one sex may suffer more trouble … from the invisible world than the other.’”

Brumberg’s book came out twenty years ago, at the cusp of the internet as we know it. Since then, of course, it has become exponentially easier for people with eating disorders of all descriptions to seek both reinforcement and a way out. I asked my Twitter followers where people with anorexia were gathering online these days. I had heard that Tumblr and Instagram had cracked down on “pro-ana” posts, but had not followed the trend closely.

I was surprised to hear that there was a community of anorexia encouragement on Twitter itself, my medium of choice, where body-positive thinkers like the anonymous and righteous @YourFatFriend abound. The hashtags that unite this eating-disorder community include #proana, #thinspo (thin inspiration), #meanspo (dieting bad cop), and #sweetspo (good cop). “Personally I like hunger pangs cause I think of them as a little chainsaw sawing away at the fat,” writes one member of the group. “Hunger pains are victory pains,” writes another. “Currently on my 3rd fast day I’m so proud. Hunger is beauty,” says a third. The more posts I read, the worse I felt about myself, the state of girlhood and womanhood, Twitter, and humanity generally. I found myself anxiously touching my thighs as I read, wondering how and when I could make them go away.

I returned to Byer’s book. Her stance is proud, a rainbow of power poses, a cornucopia of fabrics and patterns and wigs and accessories. A classic double-edged compliment for fat women is “You have such a pretty face.” (Unsubtle subtext: “So get to work to match it with a pretty body.”) Byer has a beautiful comedian’s face, so motile she can do ingenue, pinup, rascal, girl next door, performative “influencer,” and lovable maniac, probably in a single session. Her body is equally agile and capable of languor, cheer, and comedy.

Brumberg’s book came out twenty years ago, at the cusp of the internet as we know it. Since then, of course, it has become exponentially easier for people with eating disorders of all descriptions to seek both reinforcement and a way out.

For Black people specifically, Patia Braithwaite writes in a recent essay, it is imperative to tap into “happiness and levity”; she notes, “There’s also the Black Joy movement, sprouted alongside Black Lives Matter, which celebrates the happiness, playfulness, and freedom that undergird social justice.” Byer and Newmoney’s collaboration is Black joy, fat joy, and the riotous joy of spectacular fashion. For me, it undid the dread and nausea of anorexia Twitter in an instant, replacing them with admiration and a mental note to watch Byers’s next set online.

Femininity is tricky. Like many millions of women, I inherited the allure of the wilting girls in Brumberg’s book. The draped, skeletal figure, surrounded by relatives frantic with worry: why is this an appealing aspiration? What does the emancipated female human have to do with this wraith’s stunted agency? Without complete equality, weakness, silence, and proximity to death are still useful weapons in our arsenal. I, too, would like to sup on a tulip like an early modern waster-away, to rock designer sheaths like Jean Nidetch, to have the uncanny control of Kafka’s hunger artist.

But modern fasters must be sensible. The very word for dieting, as Meltzer notes, “comes from the ancient Greek word diaita, meaning ‘a way of life.’” I measure my spoonfuls like the Slow-Eater-Tiny Bite-Taker in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, step my steps, continue to lose. This loss is more dutiful than triumphant and carries with it no holy highs. (There is built-in virtue: by tracking food, I earn rewards, like the opportunity to donate food to a hungry family—hungry, that is, not by choice.) Each day I weigh myself, record the number, and see the decimal points rise and fall in minute increments like an earnings report or a child’s drawing of the ocean. The waves trend downward; I cannot see the other shore.

In his memoir, Life Itself (2011), Roger Ebert wrote,“It is useful, when you are fat, to have a lot of other things to think about. If you obsess about fat, it will not make you any thinner, but it will make you miserable.” There is something better than distraction, though: freedom. The singer Lizzo, who recently appeared on the cover of Vogue, told a reporter, “I think it’s lazy for me to just say I’m body positive at this point. It’s easy. I would like to be body-normative. I want to normalize my body. And not just be like, ‘Ooh, look at this cool movement. Being fat is body positive.’ No, being fat is normal. I think now, I owe it to the people who started this to not just stop here. We have to make people uncomfortable again, so that we can continue to change. Change is always uncomfortable, right?”

The very word for dieting, as Meltzer notes, “comes from the ancient Greek word diaita, meaning ‘a way of life.’” I measure my spoonfuls like the Slow-Eater-Tiny Bite-Taker in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, step my steps, continue to lose. This loss is more dutiful than triumphant and carries with it no holy highs.

That change is imperative to fighters of fatphobia and weight-based discrimination and involves more than self-acceptance, as transformative as that can be. It requires reforming the clothing and travel industries, equity in food access and healthcare, media representation, the well-documented wage gap between fat and thin, and a culture of relentless bullying in person and online, which takes its most recent form in blaming fat people for dying of the coronavirus.

For herself, Nicole Byer has found this freedom, but is gentle with her readers. “Like anything else in life, something new takes a hot-ass minute to get used to, so if you need to be #brave alone at home for a bit, that’s okay. You can take your time.”