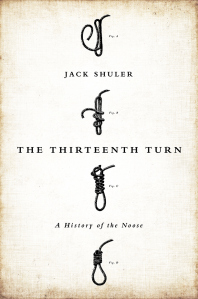

A noose is not simply a knot. To members of the International Guild of Knot Tyers, it is Knot #1119 in The Ashley Book of Knots. Expert knot tyers will easily recognize it as one of a family of slip knots, a knot made by wrapping a rope thirteen times around a central core of rope. Though ideal for use in ship’s rigging or when fishing, Knot #1119 is rarely used for such purposes but is instantly recognizable by nonexperts as the “hangman’s knot.” It is, as Jack Shuler remarks in his book, The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose a “deliberate” knot, not tied quickly or under pressure; to tie it requires being taught. Some versions have as few as four turns, but it is believed by some that thirteen best serve its purpose as a killing tool: thirteen turns make it more difficult to loosen from victim’s neck, and, when positioned at the side of the head, the greater length of the knot offers the best chance of breaking the neck and bringing on death.

As an instrument of intimidation, repression, and terror, it has served throughout American history as both symbol and reality to enforce a racialized regime or power over persons and groups who might challenge it. Like other “rites of violence” that Natalie Davis has explained to us, the noose is “a kind of cultural technology, that is taught and learned.” Following her insight, Shuler asks that “we should reflect on how we learn to hate and how we learn to kill. These things do not come out of thin air.” He is surely correct: the lynch mob thrives in the fetid air of race hatred, a tradition taught and learned. Though used against outsiders of all races, it has been primarily an instrument of terror over black Americans: from 1889 to 1918, when the epidemic of lynching was at its peak, the NAACP counted 3,224 lynchings—702 of whites and 2,522 “Colored.” The state rarely stepped in to halt this; local law enforcement officials and leaders, if not actually leading the mobs, stood by idly. Prosecution was virtually impossible. Efforts to enact federal legislation failed consistently. To this day, there is no federal law against lynching.

Lynchings became public spectacles, advertised and announced in advance and requiring special trains to accommodate crowds who flocked to gawk and have their pictures taken with bodies swinging behind them—easily the most grisly of twisted “selfies” imaginable. The killing, however, was only the beginning of this spectacle of atrocity: bodies were purposefully left hanging as a warning to others. Onlookers dismembered them, taking body parts home as souvenirs to display. In many towns, the lynchings were the largest public gatherings ever assembled. For those who could not attend, picture postcards were produced and sold, with buyers proudly boasting of their participation. Not until 1908 did Congress act to extend the anti-obscenity Comstock Law to bar from the mails any subject matter “tending to incite arson, murder, or assassination,” but the practice continued. Photographers had a thriving business in reproducing and selling the gruesome record of the inhuman spectacle for decades.

Local law enforcement officials and leaders, if not actually leading the mobs, stood by idly. Prosecution was virtually impossible. Efforts to enact federal legislation failed consistently. To this day, there is no federal law against lynching.

One such photograph, taken at Marion, Indiana, in 1930, stands at the center of Shuler’s book and also figures prominently in James Allen’s Without Sanctuary (2000). After the robbery and murder of a white man, three black men were arrested and jailed for the crime and, so it was rumored, for the rape of his female companion. Soon the victim’s bloody shirt appeared hanging from a window at city hall. Within hours the jail was mobbed, and two of the three men were hanging from a tree at the courthouse square. The bodies of the two, Abram Smith, and Thomas Shipp, were left hanging until the next morning, after the crowd had taken its souvenirs. But before the two were taken down, a local photographer was summoned to record the scene, whose onlookers betray the ghoulishly festive nature of the event. As if the meaning of the act needed clarification, one spectator is shown pointing to the bodies. The photographer, who usually recorded weddings and church events, worked tirelessly for days to meet the demand, churning out copies to sell for fifty cents each. This (Photo 27) and other photos can be seen at withoutsanctuary.org.

The photos were seen nationally, published in The Crisis and appearing in The Chicago Defender with the caption, “American Christianity.” A teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx recalled: “Way back in the early Thirties, I saw a photograph of a lynching published in a magazine devoted to the exposure and elimination of racial injustice. It was a shocking photo and haunted me for days.”

The teacher was Abel Meeropol, who put his thoughts into a poem that he soon set to music. As sung by Billie Holiday, “Strange Fruit” became one of the most influential protest songs of the twentieth century:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Shuler recounts Meeropol’s story, but he omits a remarkable coincidence that illustrates the book’s fundamental importance of “teach[ing] us about the underside of our progressive narrative of freedom, justice and the rule of law.” In 1941 “Strange Fruit” and Meeropol’s membership in the Communist party brought him to the attention of a New York state committee investigating communist influence in schools. He was asked if the party had paid him to write the song. His denied it and eventually left the party, as well as his teaching career, but found himself blacklisted as a writer in the 1950s. The web of his story, and its place in “the underside of our progressive narrative,” however, spread more widely. In 1953 he was asked to be a pallbearer for Julius and Ethel Rosenberg after their execution for espionage. Later that year he attended a Christmas party at the residence of W. E. B. Du Bois, who had publicly campaigned against lynching. At that party Meeropol met the Rosenbergs’ two orphaned sons; he and his wife adopted them.

As a young man Du Bois had learned of the extent of lynching from the writings of journalist Ida B. Wells, and he took up the cause in The Crisis. As he explained the phenomenon in 1911, “Blackness must be punished,” he wrote. “Blackness is the crime of crimes … It is therefore necessary, as every white scoundrel in the nation knows, to let slip no opportunity of punishing this crime of crimes.” Du Bois was correct: English common law had never recognized race as a category, but blackness had become a legal classification, to be enforced and punished by law and, where legal coercion was not available, by the extralegal power of the noose. Shuler’s rich and disturbing account of the power of the noose as “synecdoche, a part that stands for the whole,” brings together a history that stands as a shameful example of how the law can be twisted and defied where necessary, to enforce a race-based inferior caste alien to the common law. Shuler might well have included the case of Ed Johnson, a black man accused of rape in Tennessee in 1906, whose fate is the subject of Contempt of Court (1999) by Mark Curriden and Leroy Phillips. Johnson’s innocence was obvious, had he not been the defendant in a trial that Oliver Wendell Holmes called “a shameful attempt at justice.” Two black attorneys sought and obtained a stay of execution from the Supreme Court of the United States, but a mob tore him from jail and lynched him, in direct defiance of the nation’s highest court. Hanging Johnson did not suffice to serve the rules of lynch law: to his body the mob pinned a note, “To Justice Harlan. Come get your n—– now.” The mob that killed Johnson made it clear that the noose was a higher authority than the Supreme Court, and mobs of the sort that killed Smith and Shipp in Indiana meant that its writ ran far beyond the South.

The noose also exploits the complicity of a legal system, which to this day has, lamentably, not fully purged itself of those who condone or subscribe to what Susan Sontag identifies as “a belief system, racism, that by defining one people as less human than another legitimates torture and murder.” Missouri has seen numerous examples where, as in Marion, “justice was never pursued.” In his book, Civil War St. Louis (2001), Louis Gerteis writes of Francis McIntosh, a free black boatman who in 1836 resisted arrest when trying to help two fellow sailors escape arrest, and was himself arrested. Told that he would go to jail for five years, McIntosh assaulted and stabbed a white deputy constable, who later died of the wound. McIntosh surely would have been executed for murder, but courthouse law was neither as swift nor as terrifying as lynch law. McIntosh was pulled from jail, chained to a tree at what is now 10th and Market Streets (where Richard Serra’s “Twain” now stands) and burned alive. Although a grand jury was convened to determine if the lynching should produce criminal indictments, lynch law did not recognize any crime. Judge Luke Lawless took command of the grand jury and instructed it in such a way as to make any charge unlikely: the only question for the grand jury to decide was “whether the destruction of McIntosh was the act of the ‘few’ or the act of the ‘many.’” Only in the former case would an indictment be proper, he explained. Even if specific individuals could be singled out as leaders, he added, the mob’s actions were mitigated by the threat of abolitionism. Appealing to racial fears, he offered his own interpretation of what had happened, describing McIntosh’s actions as typical of “similar atrocities committed in this and other states BY INDIVIDUALS OF NEGRO BLOOD AGAINST THEIR WHITE BRETHREN.” The grand jury failed to indict.

Shuler wrote Thirteenth Turn, he tells us, to reveal the “still underdiscussed narrative of violence in American history,” which “includes both a kind of legal ‘justice,’ the death penalty, meted out by the state—with all the biases that kind of justice entails—as well as another, extralegal ‘justice,’ the democracy of the mob.” Any dialogue that we attempt as a way to achieve racial reconciliation is doomed, he observes, because “there is no real effort to address the heart of the matter, which is an ugly and complicated history.”

And ugly it is. Richard Wright, like all too many African Americans growing up in the South, knew the power of the noose, having lost two family members to its efficient strangulation. As he recalled in Black Boy,

“The things that influenced my conduct as a Negro did not have to happen to me directly; I needed but to hear of them to feel their full effects in the deepest layers of my consciousness. Indeed, the white brutality that I had not seen was a more effective control of my behavior than that which I knew.”

The unseen terror behind the image of the noose was sufficient.

Its history has been complicated, too. Missouri, despite is regrettable record on race, can look to Congressman Leonidas Dyer, a white Republican who represented a majority black district in St. Louis. A graduate of Washington University’s law school, he was appalled by the bloody race riot in East St. Louis in 1917 and worked tirelessly to pass a federal antilynching law. To criminalize lynching, his bill contained the following definition:

The phrase ‘mob or riotous assemblage,’ when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without the authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense.

Aware that states’ rights Congressmen would deny federal authority over a local crime and a private act, he defined the crime as involving state action by implicating local officials who failed to provide equal protection to black citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment. His bill passed the House in 1922, 1923, and 1924, but each time it was foiled by filibustering efforts of southern senators.

Shuler uses the strands of the noose as metaphor for the many paths that racialized violence has taken, and the turns of the knot maker as controlling and concentrating its power. The noose has largely replaced the burning cross and the hanging effigy, and so, too, has racialized violence assumed new and different forms, wielded by officials of the law as well as by self-appointed guardians of racial supremacy. It does not really matter whether the knot has seven turns (for the seven seas), nine turns (a cat’s lives) or thirteen (bad luck): the message is the same.