There was not much to Khe Sanh before late 1966. It was a mountain valley in the northwest corner of South Vietnam, a few miles from the border with Laos. The French had planted coffee on its slopes during their time ruling Indochina from the late 19th century until 1954; a few Americans knew Khe Sanh as a place to hunt tigers. The Bru people who lived there wished to be left alone by the government in the southern capital of Saigon and the war that sometimes transited their land. But in September of that year, General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, became convinced that his Communist enemies were planning a full-scale assault on the South, “with Khe Sanh,” he wrote to President Lyndon Johnson, “being the main event.” The valley stood near infiltration routes off the Ho Chi Minh Trail, along which North Vietnamese units made their way into the South, and was thus, he thought, a likely jumping off point for an enemy offensive, evidence for which military intelligence was collecting at an increasing pace. Westmoreland began to reinforce the valley, extending its small airstrip so as to allow large transport planes to land, and sending in a battalion of Marines (1,500 men), to be supplemented, in early 1968, by four battalions more, with others stationed nearby.

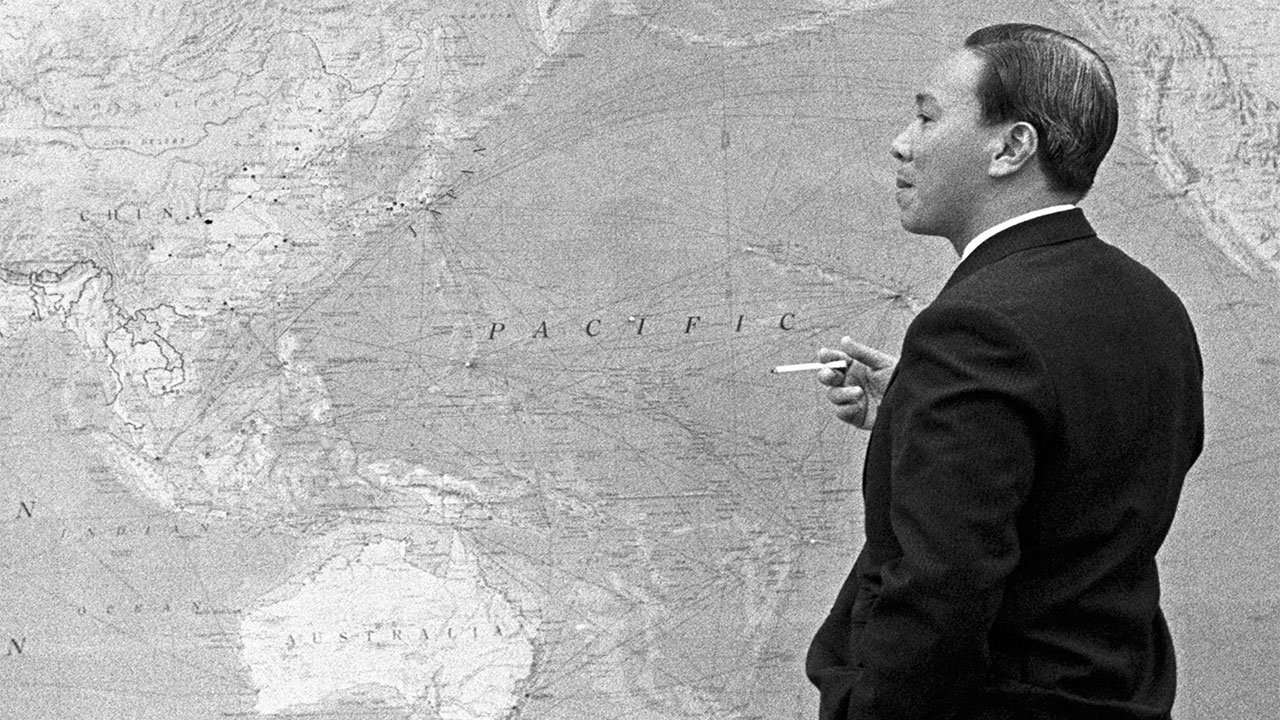

Westmoreland hoped to lure the North Vietnamese, and their southern-based allies, the National Liberation Front (the NLF, or Viet Cong), into positions that would expose them to the remorseless efficiency of American artillery and airpower. He was not wrong that Hanoi was massing troops near Khe Sanh. In mid-1967, hardliners in the Hanoi Politburo, led by Le Duan, had proposed a strategy of General Offensive-General Uprising (GO-GU) in the South, whereby North Vietnamese main force units would draw the Americans away from cities, allowing the Viet Cong to spearhead the overthrow of the “puppet government,” helpless to sustain itself in the absence of U.S. military forces. (Ho Chi Minh and his leading general, Vo Nguyen Giap, opposed the GO-GU strategy, but they were outmaneuvered and overruled.)[1] Khe Sanh was the focal point of efforts to lure the Americans into the countryside. By late 1967, North Vietnamese and U.S. troops were fighting in the hills around the base, evoking in some Americans flashbacks of the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu 14 years earlier. Khe Sanh would be different, Westmoreland assured his doubters. U.S. firepower would be massed against the Communists. Besides, American soldiers were not the French.

… despite Westmoreland’s conviction that the enemy offensive was aimed at Khe Sanh, others insisted that reinforcing the remote base was folly, and that if the enemy attacked throughout the south, ARVN resistance would quickly crumble. Lt. General Fred Weyand pressed his case vigorously enough that he was allowed to hold 15 of his battalions in positions closer to Saigon. Weyand’s obduracy likely saved South Vietnam in 1968.

Neither were the Americans’ allies, the forces of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Built and supplied generously by the United States, the ARVN by early 1968 included some units that were well trained and willing to fight. Yet the master they ultimately served, President Nguyen Van Thieu, was uninspiring, and the state he represented was convincingly portrayed by its opponents as undemocratic, corrupt, and illegitimate, an American creature. American officers had little faith in ARVN forces. So, despite Westmoreland’s conviction that the enemy offensive was aimed at Khe Sanh, others insisted that reinforcing the remote base was folly, and that if the enemy attacked throughout the south, ARVN resistance would quickly crumble. Lt. General Fred Weyand pressed his case vigorously enough that he was allowed to hold 15 of his battalions in positions closer to Saigon. Weyand’s obduracy likely saved South Vietnam in 1968.

Even as they sacrificed thousands of soldiers to the Americans in Khe Sanh, thereby following the Maoist dictum to create an “uproar in the East” while mounting a “strike in the West” (with the compass in this case reversed), the North Vietnamese and NLF poised for a blow at the heart of Thieu’s power. Early in the morning of January 30, 1968, with the arrival of the Lunar New Year, or Tet holiday, Communist forces launched an assault on Saigon and other southern cities. They rightly anticipated that southern forces would be celebrating with their families and joining in the general revelry; indeed, scores of those present at the start of the attack assumed that the first explosions they heard were firecrackers heralding Tet. The enemy struck five of six major cities, most provincial capitals, and 64 district capitals. They shelled Tan Son Nhut Airport outside Saigon—the world’s busiest—attacked the presidential palace, the national radio station, and the ARVN’s staff headquarters. Most shocking to the Americans, NLF fighters blew a hole in the wall of the U.S. embassy and occupied the courtyard of the compound, killing several guards and forcing officials to take cover inside the building. Security forces trundled the U.S. ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker, still in his pajamas, into an armored personnel carrier, and had him driven away.

The fighting produced uncommon savagery even in a savage war. In Hue, the NLF murdered several thousand southern civilians—called “blood-debtors” because of their alleged persecutions of the people—following hasty trials in “people’s courts.” After years of denial, some northern officials admitted that these executions had taken place, and that they were, admitted a Vietnamese historian, “a stain on the revolution’s record.”[2] The Americans produced their own record of atrocity and denial. Having annihilated the enemy-held town of Ben Tre with the lavish use of firepower, an officer told a reporter blandly that “it became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it”—a logic whose perversity seemed to characterize the U.S. war effort generally. In mid-March, while the reverberations of Tet continued to shake the countryside (and as the North prepared a second offensive), an American rifle company, commanded by Lieutenant William Calley, had plunged into the small village of My Lai 4 and slaughtered hundreds of unresisting civilians. The massacre was hushed up for over a year, and then exposed only because Corporal Ron Ridenhour, who had learned of the incident from witnesses, persisted in writing letters to the president and other officials, demanding that they act. (President Richard Nixon blamed the whistle-blowers and those who subsequently publicized the story: “It’s those dirty rotten Jews from New York who are behind it.”)[3]

Westmoreland claimed victory: “The enemy exposed himself by virtue of his strategy and he suffered heavy casualties,” he told reporters. “As soon as President Thieu … called off the [Tet] truce, American troops went on the offensive and pursued the enemy aggressively.” … Privately, in Vietnam and Washington, there was far less optimism.

Despite Le Duan’s best-laid plans, the offensive failed to achieve its military objectives. Saigon was shaken but held; the U.S. embassy was retaken after several hours, with all 19 of the NLF sappers killed or badly wounded. Fred Weyand’s forces, withheld at his insistence from the area near Khe Sanh, drove the enemy from Tan Son Nhut, inflicting heavy losses. The Americans regained the Citadel in Hue only after several weeks of harrowing and ruthless fighting. Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap had opposed the Tet Offensive, and their fears, dismissed at the time, were in some measure vindicated by the ruinous death toll suffered by the NVA and especially the NLF, which was nearly demolished. What had happened? The uprising Hanoi’s planners had always anticipated for the south was far less general than they expected. Some ARVN units broke under pressure, but others fought bravely, out of surprising loyalty to their government or, more likely, out of desperation to survive and a desire to protect their families. And, despite Westmoreland’s staggering miscalculation of enemy intentions, American forces, and force, were enough to drive the Communists off. Westmoreland claimed victory: “The enemy exposed himself by virtue of his strategy and he suffered heavy casualties,” he told reporters. “As soon as President Thieu … called off the [Tet] truce, American troops went on the offensive and pursued the enemy aggressively.”[4] Less than a month later, he joined General Earle Wheeler, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to request from Washington an additional 206,000 troops, in order to take advantage of the “great opportunity” afforded the United States to finish the job against its weakened opponent.

Privately, in Vietnam and Washington, there was far less optimism. Wheeler wrote that the Tet Offensive had been “a very near thing,” indicating that any prospect of the ARVN defending the country by itself was delusional. Influential journalists, including Joseph Kraft and Walter Cronkite, warned that the war effort was at best stalled. The systems analysts at the Pentagon concluded, in their peculiar language, that adding more U.S. troops would not promise “any success in attriting the enemy or eroding Hanoi’s will to fight,” while their boss, the outgoing Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, glumly accepted their statistical estimates of enemy strength and endured sleepless nights, wondering what had gone wrong. Members of both parties in Congress, having been by their account excluded for years from meaningful involvement in policy or strategic discussions of the war, were furious, and promised to view any more attempts by the administration to increase the American presence in Vietnam with a jaundiced eye. Public support for the war continued to slide; Americans were particularly appalled when they saw photographs and film of the South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan execute a prisoner on a Saigon street with a pistol shot to the head.

President Lyndon Johnson had chosen to go to war in late 1964. He worried that American prestige, and his own reputation, could not afford a humiliating loss in Vietnam. He believed in the need to contain communism, and he knew that the Soviet Union and China were supporting North Vietnamese efforts to reunite their country. He did not wish to expand the war, but in his zeal to halt the Communists on the battlefield he had adopted a strategy of sending more and more troops to the theater—there were 670,000 there on the eve of Tet ’68—and increasing the bombing of targets on both sides of the 17th parallel that had since 1954 divided the two Vietnams. When the leaders of South Vietnam engaged in corrupt practices and political machinations and their generals found ingenious ways to avoid fights, LBJ put the best public face on the situation and insisted that there was no choice but to go on. In fact, he was weary of the war. He wanted more than anything to expand the cluster of domestic reforms he called The Great Society: Civil Rights legislation, a campaign against poverty, laws to improve health, education, and consumer protection. Vietnam was a distraction and a financial sinkhole, that “bitch of a war” threatening “the woman I really loved—the Great Society.” In March, the economy faltered badly, the result of sustained inflationary spending on the war and Johnson’s domestic programs. The dollar weakened dramatically, and the country suffered a massive gold drain that led to the closing of the gold market in London.

Years earlier, the president had told his aide, Bill Moyers: “I feel like a hitchhiker caught in a hailstorm on a Texas highway—I can’t run, I can’t hide, and I can’t make it stop.” [5] Tet made the hailstorm far worse. In its aftermath, the president made several changes in his Vietnam policy. Discouraged by the pessimism of his new Defense Secretary Clark Clifford and a group of once-hawkish senior advisors known as the “Wise Men,” he rejected the generals’ request for a significant troop increase and removed Westmoreland from command in Vietnam, replacing him with General Creighton Abrams. Johnson became more receptive to a bombing halt over at least parts of North Vietnam, and he demanded that South Vietnam take greater responsibility for its own defense, a posture later described as “Vietnamization.” Yet the public’s faith in Johnson had been shaken. On March 12, New Hampshire held its presidential primary. Eugene McCarthy, a Democratic senator (and poet) from Minnesota who had made withdrawal from Vietnam virtually his only campaign position, won a shocking 42 percent of Democratic votes. When the write-in votes were counted, it emerged that McCarthy had in fact beaten the president. It was not that New Hampshire Democrats accepted McCarthy’s message of peace: most of those voting for him, it turned out, favored a more aggressive stance in Vietnam. McCarthy triumphed because he was not Lyndon Johnson.

Vietnam was a distraction and a financial sinkhole, that “bitch of a war” threatening “the woman I really loved—the Great Society.” In March, the economy faltered badly, the result of sustained inflationary spending on the war and President Johnson’s domestic programs. The dollar weakened dramatically, and the country suffered a massive gold drain that led to the closing of the gold market in London. Years earlier, the president had told his aide, Bill Moyers: “I feel like a hitchhiker caught in a hailstorm on a Texas highway—I can’t run, I can’t hide, and I can’t make it stop.”

The president scheduled a televised address to the nation on the last night of March. “I’ve got an ending,” he told his speechwriter Harry McPherson, who guessed what it might be. In the speech Johnson signaled his interest in talks with Hanoi by ordering a halt to bombing North Vietnam, except for areas just north of the demilitarized zone, “where the continuing enemy buildup directly threatens allied forward positions.” He noted with approval an apparent new assertiveness in Saigon—the government had just mobilized over 100,000 additional troops—and stated his willingness to negotiate with North Vietnam in “early talks.” Americans, he pleaded, should “guard against divisiveness and all its ugly consequences.” Finally came the President’s surprise ending: with the war still raging and “America’s future under challenge … I do not believe I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office. … Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”[6] Americans reeled when they heard Johnson renounce his own succession. For all his troubles, the president had seemed to delight in his job. And who would replace him on the Democratic ticket?

Earlier that day, LBJ had briefed his vice president, Hubert H. Humphrey, about the last lines of his speech. “You’d better start now planning your campaign for President,” he told Humphrey. The vice president had not been ready for this. He and Johnson had entered the Senate together in 1949, and Humphrey had long championed the progressive social programs advanced by the Great Society. The two men were well matched politically. In 1964, Johnson secured for the ticket much of the South and West, while Humphrey delivered the votes of Northern liberals otherwise inclined to suspicion of Johnson, who struck them as a devious Texas pol and was obviously not Jack Kennedy. While Humphrey had grown uneasy at the escalation of the war and voiced doubts about it in private, he was disinclined to make his concerns public, not wishing to cross the President and thereby jeopardize his own presumed political future. Johnson and Humphrey may have been “friends since the early 1950s,” Walter LaFeber has written, “but in the same way a gravedigger is friends with his shovel.”[7] Johnson’s enthusiasm for a Humphrey victory in November was well contained. That he hoped Humphrey would win at all was the result of his utter loathing for the others in the race.

The other Democrats included McCarthy, the one-issue candidate, “a body,” as one antiwar organizer put it, and at first the only Democrat willing to challenge a sitting president. The diffident senator found himself the darling of the antiwar left, which rejected Humphrey as an apologist for war. With Johnson’s withdrawal from the race came a far more formidable challenger: Robert Kennedy. The late president’s younger brother, Bobby Kennedy had turned increasingly dovish, and he was by early 1968 a harsh critic of Johnson’s Vietnam policies. He demurred from challenging the president until McCarthy had exposed him in New Hampshire, at which point he sent his brother Ted to inform McCarthy that Bobby was going to enter the race. McCarthy and many of his supporters were furious. “We woke up after the New Hampshire primary like it was Christmas Day,” recalled a McCarthy staffer. “And when we went down to the tree, we found that Bobby Kennedy had stolen our Christmas presents.”[8] Opportunistic as he doubtless was, Kennedy had political assets that McCarthy lacked, among them a general affection for the Kennedys, at least among Democrats, a record of public service that progressives admired, and the support of African Americans and labor unions who had received little attention from McCarthy and who were thus unexcited by his candidacy. Bobby connected well with audiences, and polls showed that he was a far more effective opponent than McCarthy for the likely Republican nominee, Richard Nixon. And Alabama Democrat George Wallace, a staunch segregationist, appealed to Southern and working-class whites who felt neglected by government social programs and ignored by the mainstream parties who, Wallace implied, were merely pandering to blacks. Wallace would join the race as an Independent.

Earlier that day, LBJ had briefed his vice president, Hubert H. Humphrey, about the last lines of his speech. “You’d better start now planning your campaign for President,” he told Humphrey. The vice president had not been ready for this.

The tumult and violence of the war seemed in evidence everywhere in the early months of 1968. In January, the North Koreans had seized the U.S. intelligence ship Pueblo, insisting that it had been spying on them from within the 12-mile limit of their territorial waters. The Johnson administration was unable to secure the release of the crew until December, and only after it offered an ersatz (but humiliating) admission that the ship had been spying. On April 4, Martin Luther King was assassinated as he stood on a motel balcony in Memphis. For years the most eloquent and powerful voice on behalf of civil rights in the United States, King had lately joined critics of the war, calling it a distraction from more serious problems, an atrocity, and a reflection of American racism. Now over 100 U.S. cities burst into violence, including Washington, where smoke from burning neighborhoods engulfed the White House and the Capitol. Two months later, Robert Kennedy was shot dead in Los Angeles as he exited a hotel through its kitchen. The night before, he had narrowly beaten McCarthy in the California Democratic primary, securing the state’s 174 delegates, roughly one-eighth of those needed for the nomination. The nation grieved once more. The Democrats were thrown into turmoil.

Vietnam shadowed both party conventions that summer. The Republicans, as expected, chose Nixon as their nominee in early August. On Vietnam, the candidate offered Americans vague promises: that he would be candid with them, that he would talk with the Soviet Union about the intractability of Hanoi, and that he would give “urgent attention” to Vietnamization, which was what Johnson was already doing, with an eye toward the withdrawal of U.S. troops. His insistence on “law and order” in the country was rightly understood as cracking down on urban violence (rather than the racial discrimination that induced it), but was also meant as a warning to the Communists in Vietnam. The Democratic convention in Chicago later that month was more eventful. As thousands of demonstrators, peaceful and otherwise, poured into the city streets, to be met by a police force intent on disciplining them, delegates inside the International Amphitheatre quarreled into the night about the nominating process and the party platform concerning the war. Antiwar delegates supporting McCarthy or Senator George McGovern, who had entered the race in an attempt to assume Kennedy’s mantle, called for an unconditional bombing halt and a broadening of the Saigon government to include the NLF. From the White House, Johnson bullied Humphrey and the moderates into rejecting these planks, and his position carried the day. Humphrey won the nomination, to the fury of many of those inside and outside the hall. In the meantime, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, putting an end to a reform movement that had flowered briefly that summer. The protestors saw parallels between their experience in the streets of Chicago and those of the Czechs who battled the tanks of Soviet authoritarianism. Humphrey, an optimistic man, tried to put the best face on his triumph. Many observers concluded that he had inherited a corpse.

As it turned out, the election that November was—perhaps surprisingly, given the Democrats’ fractiousness—quite close. Humphrey gradually moved away from Johnson’s position on the war, and as he did so his voice became his own. Fear of a Nixon (or even a Wallace) presidency brought around traditional Democrats, including labor unions and some antiwar moderates. And, after toying with Humphrey for months, threatening him at one point with the loss of Texas if the vice president failed to adhere to Johnson’s Vietnam policy, the president finally moved to help. On October 31, less than a week before the election, Johnson announced a bombing halt and declared that peace talks, free of preconditions, would begin in Paris just after election day. The polls tightened immediately. Nixon was furious. But he had a final card to play. For weeks, Anna Chenault, the Chinese-born widow of Claire Chenault, commander of the Flying Tigers air squadron in World War II China, had schemed on Nixon’s behalf, secretly informing Thieu that he should refuse to enter talks with North Vietnam because to do so would help Humphrey, and a Nixon presidency would be far more favorable to South Vietnam than a Humphrey administration. Thieu duly held out, effectively stalling Johnson’s belated peace overture. On November 5, Humphrey fell less than a million votes short (out of 72 million cast). Many insiders were convinced that the Nixon-Chenault approach to Thieu, captured by illegal wiretaps and known to Johnson and Humphrey before the election, had enabled Nixon’s narrow win. The year ended with talks on hold as Nixon assembled his cabinet and advisory team. His most prominent choice on the foreign policy side was Harvard Professor Henry Kissinger as National Security Advisor. In keeping with the ethical suppleness of the president-elect, Kissinger had over the summer and fall exploited his contacts in the Johnson administration to gather then leak information concerning Vietnam policy to the Nixon camp. His loyalty was thus rewarded.

Vietnam shadowed both party conventions that summer. The Republicans, as expected, chose Nixon as their nominee in early August. … The Democratic convention in Chicago later that month was more eventful.

While 1968 was decisive for Vietnam and the United States, the war would drag on for many more years. For reasons both political and geo-strategic, Nixon and Kissinger wished it over, but they would not leave before first attempting to punish the North for its repeated trespasses into the South, and pumping up Thieu’s regime with an abundance of military hardware in the vain hope that it might finally defend itself. The administration took the war to the neighboring states of Cambodia and Laos, wherein Communist troops were sheltering and transiting into South Vietnam. (Both of these incursions proved failures.) Talks sputtered on intermittently, yielding an agreement in the fall of 1972, under which the Americans would withdraw their remaining troops (Nixon had started slowly bringing them home three years earlier), receive from the North their prisoners of war, and permit a National Council of Reconciliation and Concord, representing the NLF, the Saigon government, and a body of neutralists, to organize elections for a new government in the South. North Vietnamese troops would be allowed to remain in the South, while Hanoi dropped a longstanding demand for the removal of Thieu. The hitch was that Thieu had not been consulted by his American benefactors, and Kissinger, to his anger and astonishment, proved unable to convince him to accept the deal. When as a result Hanoi’s negotiators departed Paris in a huff, Nixon unleashed a bombing campaign against northern cities that left 1,600 civilians dead and cost the Americans 15 B-52 bombers. Both sides, newly-sobered, returned to negotiations. In January 1973 they settled on terms similar to those reached the previous fall; this time, Nixon demanded Thieu’s acquiescence. The Americans came home. More than 58,000 had died in the war, more than a third of these during Nixon’s presidency. And just over two years later, a powerful North Vietnamese offensive put an end to South Vietnam. The country was reunited, under Communist rule.

What were the lessons and legacies of Vietnam 1968, the year the war turned? In the aftermath of war, a number of conservative (or “revisionist”) scholars and commentators claimed that the United States had fought honorably for freedom in Vietnam. “We were trying to save the Southern half of that country from the evils of Communism,” wrote Norman Podhoretz—and the horrors visited on the South following “liberation” in 1975 vindicated the moral value of that effort and shamed, or should have shamed, the antiwar left.[9] Walt W. Rostow, an adviser to Kennedy and Johnson, insisted to his dying day (2003) that U.S. intervention in Vietnam had protected other Southeast Asian countries, including Singapore and Indonesia, from Communist invasion or insurgency, buying time for them to establish nominally democratic and certainly anti-Communist regimes.[10] Lewis Sorley noted in the best-known histories of the American war the relative neglect of the period after Tet, and he argued that the offensive had so weakened the enemy that if the United States had not stinted thereafter on political, military, and financial support and had committed itself firmly to training the South Vietnamese officer corps and the elimination of Communist sanctuaries in Cambodia and Laos, the war might yet have been won. The Americans stood accused of abandoning the South Vietnamese.[11]

While 1968 was decisive for Vietnam and the United States, the war would drag on for many more years. For reasons both political and geo-strategic, Nixon and Kissinger wished it over, but they would not leave before first attempting to punish the North for its repeated trespasses into the South, and pumping up Thieu’s regime with an abundance of military hardware in the vain hope that it might finally defend itself.

The preponderance of evidence from which such conclusions might be extrapolated has led most observers another way. Few would claim that reunification meant justice, given the treatment visited on many South Vietnamese by the victors, but as Podhoretz also admitted that “sav[ing] Vietnam from Communism was indeed beyond our intellectual and moral capacities,” and, one might add, our political capacities too, one wonders how moral or sensible it was to persist in the war after 1968, to throw good lives after other good lives. Rostow seems to have been confused about the post-1968 history of Southeast Asia, including the aims and abilities of the North Vietnamese to carry their revolution beyond Indochina. Sorley’s argument suffers from an over-focus on the American role in Saigon’s defeat. Rather, writes Gregory Daddis, the way the war ended had “far less to do with Abrams’s strategy or congressional funding or domestic opposition than with South Vietnam’s inability to develop a peacetime national identity in a time of war”—that is, the South Vietnamese cause, and the state itself, were insufficient frameworks on which to rest the heavy burdens of war.[12]

In the aftermath of the conflict, conservative politicians claimed that a “Vietnam Syndrome” afflicted U.S. foreign relations, whereby the country was unwilling to engage in military intervention even in moments of dire need or when it might have done some good. In truth, Americans have always been reluctant to send troops to fight abroad, as their cautious response to the 20th-century world wars made clear. Many felt that Lyndon Johnson especially had tricked them, committing soldiers to Vietnam without a declaration of war, without fanfare, and piecemeal, such that they were startled to learn in early 1968 that there were nearly 700,000 U.S. troops there. Certainly, Americans responded with revulsion to the death and injuries that seemed without purpose. Still, as syndromes went, the Vietnam version was short-lived. In 1975, Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, sent troops to liberate American sailors captured—temporarily, it turned out—by Cambodians; Jimmy Carter launched a military mission to rescue American hostages in Iran (it failed); Ronald Reagan authorized the invasion of Grenada (a success) and a weighty U.S. military presence in Lebanon (241 Marines were killed there in 1983 by Islamic Jihad truck bombs); and George W. Bush sent U.S. troops to Panama in 1989 and into battle against the Iraqi invaders of Kuwait in 1991. After the Iraqis were driven off, Bush exulted: “We’ve kicked the Vietnam Syndrome!” So much for that.

The U.S. military studied carefully the lessons of Vietnam. Battles in the war were used as case studies at the service academies, where cadets gained belated respect for insurgency warfare. The myth developed, consistent with the view of Sorley and others, that cowardly civilians in Washington had prevented the military from winning the war, and officers vowed never again to commit troops to combat unless they were assured of public and government support. The draft, a source of enormous anxiety to young men and their families, was replaced in 1973 by an all-volunteer military, which sought to induce young Americans to join by appealing to their patriotism and their presumed interest in having a job and learning a skill. Reviews of the new forces were mixed. But the reputation of the military, badly damaged by Vietnam, recovered: between 1981 and 2011, the percentage of Americans expressing “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military went from 50 percent to 78 percent. There was small comfort in these statistics for Vietnam War veterans. Criticized by conservatives as losers and abusers of drugs, by many radicals as perpetrators of atrocities, they were badly neglected when they returned, often traumatized, to the United States following their tours. While the new enthusiasm for veterans generally has helped to some extent to salvage their reputation, the refrain “thank you for your service” has been murmured mostly at younger vets in uniform, and it has not made medical benefits due the soldiers much easier to obtain than they were 40 years ago.

American protest came of age during the Vietnam War, especially during and after 1968. Borrowing from the civil rights movement, youthful antiwar demonstrators marshaled rallies and marches that grew over time to attract serious attention, both positive and negative, from the media, politicians, and the public. The demonstrations bothered Johnson and tormented Nixon, and both rashly authorized repression and devious means of trying to discredit their organizers.

In economic terms, the war raised interest rates, fueled inflation, and broke consumer confidence. The gold crisis of 1968 was the most obvious manifestation of the costs of the war, and it was not soon forgotten. By the mid-1970s, other factors, especially the oil boycott and rise in oil prices, had supplanted the war as the chief source of U.S. economic difficulties. Ironically, perhaps the most lasting economic outcome of the war era was the dramatic growth of trade with Vietnam. Twenty years after the fall (or liberation) of Saigon, the United States extended diplomatic recognition to Vietnam. The two nations signed a bilateral trade agreement in 2001, leading to a quick expansion of trade between them. In 2016, U.S. exports of goods to Vietnam were worth more than $10 billion, a growth of over 820 percent in a decade. Vietnamese sales to the United States totaled $32 billion, making the U.S. Vietnam’s second largest export market, behind China. Veterans, former antiwar protestors, and the children and grandchildren of both groups, now share the experience of wearing clothing stitched in Vietnam.

American protest came of age during the Vietnam War, especially during and after 1968. Borrowing from the civil rights movement, youthful antiwar demonstrators marshaled rallies and marches that grew over time to attract serious attention, both positive and negative, from the media, politicians, and the public. The demonstrations bothered Johnson and tormented Nixon, and both rashly authorized repression and devious means of trying to discredit their organizers. The antiwar movement became a model for future protestors, just as it had learned lessons from civil rights protest. Campaigners against nuclear weapons, apartheid in South Africa, efforts to curb women’s rights, homophobia and indifference to AIDS, and other social and political ills, used slogans and strategies that reminded observers of the 1960s and 1970s. In 2018, a mass shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida inspired a campaign, by survivors and others (many under the age of 18), to demand meaningful reforms of American gun laws. A March 24 rally in Washington brought hundreds of thousands of protestors into the streets and drew widespread comparisons to the antiwar marches of an earlier time.

A vital part of the legacy of the war was the flight to the United States of thousands of Vietnamese displaced by the fighting, including large numbers of ethnic Chinese, those who had in some capacity served the Southern government or the U.S. authorities, and even some non-Communist members of the NLF, whose services were no longer required by the ideologically rigid and repressive new regime. An estimated 1.5 million fled the country in or after 1975; following harrowing boat journeys and time spent in the purgatory of Asian detention camps, two-thirds of these found their way to the United States. They were in the main rudely received. Some Americans claimed the Vietnamese were clannish and unwilling to assimilate, while others insisted that they assimilated all too well, becoming a “model minority” who took jobs from Americans and competed with their children for places in universities. Vietnamese fisherfolk were abused by their American counterparts along the southern Gulf Coast. Within the largest Vietnamese-American community known as “Little Saigon,” in Orange County, California, a vigorous culture took root, but it was one troubled by the rise of gangs, score-settling over imported political differences, and, as ever, racial discrimination. Recently, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has detained thousands of Vietnamese who have criminal records and intends to deport them to Vietnam—the country from which they fled, usually as small children, because of the American war there.

Whatever the Americans suffered, whatever vexed and confused or confounded them about the war, even as the numbers of their wounded and dead mounted and the tragedy and outrageousness of it all grew, the Vietnamese felt the brunt of the war and the staggering implications of its aftermath. “I was born in Vietnam but made in America,” writes Viet Thanh Nguyen in the opening sentence of his book Nothing Ever Dies.

There are perhaps portentous things to say about how the Vietnam War, and particularly the traumas of 1968, exposed the limits of American power, or brought an end to American innocence, or revealed once and for all the follies of hubris and imperial thinking and behavior. In the end, though, what endures is a sense of tragedy, the bewilderment of a people who cannot understand to this day what they did wrong, as they tried to save South Vietnam “from the evils of Communism.” Yet it was never this simple. Tim O’Brien was a reluctant soldier in Vietnam in 1969-70. He later wrote with eloquence about the war. In his novel Going After Cacciato, he meditates on what the Americans in Vietnam did not know: “They did not know even the simple things: a sense of victory, or satisfaction, or necessary sacrifice. They did not know the feeling of taking a place and keeping it, securing a village and then raising the flag and calling it a victory. … They did not know strategies. They did not know the terms of the war, its architecture, the rules of fair play. … They did not know which stories to believe. Magic, mystery, ghosts and incense, whispers in the dark, strange tongues and strange smells, uncertainties never articulated in war stories, emotion squandered on ignorance. They did not know good from evil.”[13]

Finally, there were the Vietnamese. Whatever the Americans suffered, whatever vexed and confused or confounded them about the war, even as the numbers of their wounded and dead mounted and the tragedy and outrageousness of it all grew, the Vietnamese felt the brunt of the war and the staggering implications of its aftermath. “I was born in Vietnam but made in America,” writes Viet Thanh Nguyen in the opening sentence of his book Nothing Ever Dies. Nguyen fled Vietnam with his family in 1975, at the age of four. “Even as a child,” he recalled, “I always knew, however dimly, that the stories of my parents were not just immigrant stories but war stories.” “Their stories needed to be told,” he insists, “but I always hesitated about telling them. ‘Terrible, terrible things,’ my mother said, having told me some things, refusing to tell me others. ‘Haven’t you said enough?’ my father said to her.”[14] What was enough, for Nguyen and for the countless Vietnamese, whose country was a war? The collective amnesia about the war from which so many Americans suffer, or (more accurately) which they embrace, is not a choice for the Nguyens and millions of others.