In the first week of January, a snowstorm named Blair blows across the middle of America and sets down a flood of white on the Midwest, twice. As the first round of snow falls down in St. Louis, Missouri, the manager of the White Castles on Olive Road is closing up early at 12:30 in the afternoon. The last fast food she serves is an order for eight double cheeseburgers, a side of fries, and a large drink. The manager gets stuck in the parking lot once, on the road twice, and ends up at a co-worker’s house for seven hours because none of the metro buses are running and the tow truck she called is running but is running late.

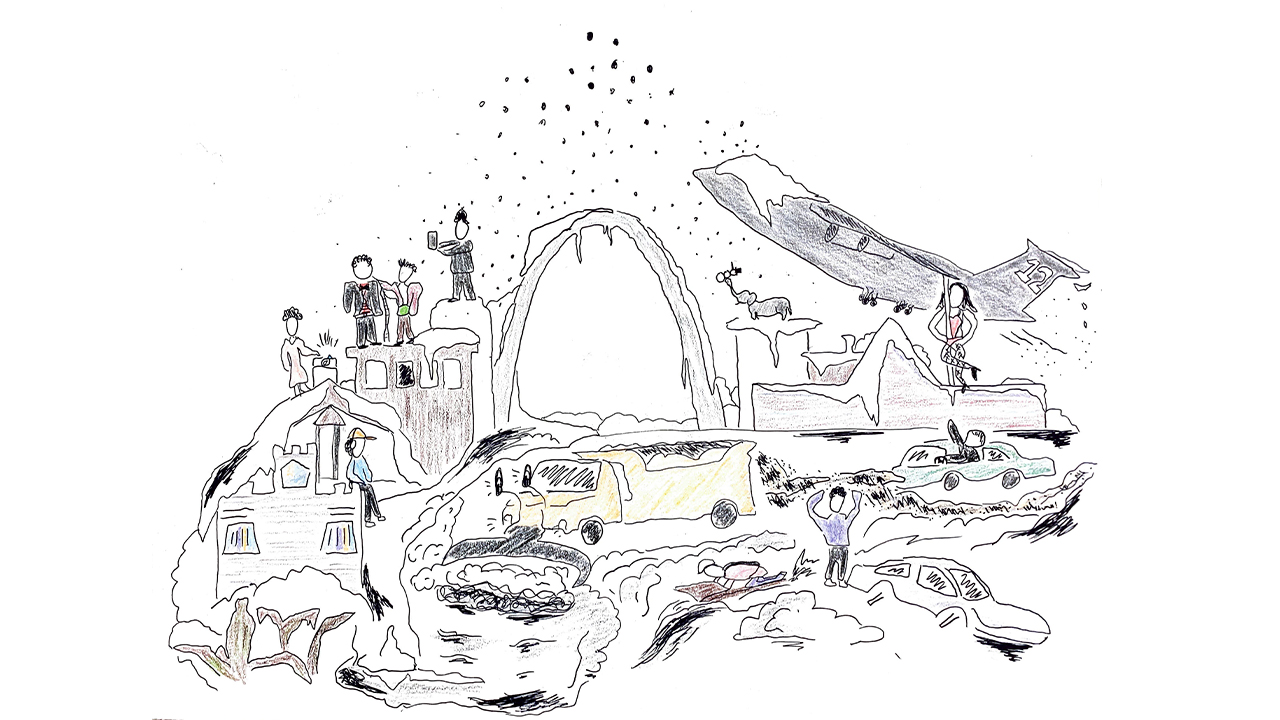

Across the river at Scott Air Force Base, eighty soldiers that make up the 12th Air Task Force (among which are six total task forces, not twelve) cannot fly away in their 840-ton C-5 Galaxy. Their deployment is postponed a few days and in the meantime, the airmen clearing the snow from the runways descend into snowball fights—acts of cold aggression on American soil.

Larry Flynt’s Hustler Club—which on Sunday is usually open at all hours except from six in the morning (when the patrons from Saturday night leave) to noon (when the patrons return and stay till Monday morning)—is fully closed.

As St. Louis is freezing, Los Angeles is burning. While a fake image of a burning Hollywood Sign circulates on social media, the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office is trying to debunk a local hoax on Facebook that says there is a serial killer in Hillsboro. The killer, the post warns, “goes around knocking on peoples’ [sic] doors claiming to be homeless & he attacks you after you let him in. He’s ruthless and very dangerous.” The sheriff says not to share the post; people do anyway.

Out west, both the big houses and the wood hovels resemble cottages; assorted horses idle in the fields of tundra; the farmers grow grey hair. Already the state roads that wind the limestone mountains are cleared and cold dead dry, just like the wind.

“Oh my goodness, there’s unbelievably kind people out here,” thinks Kevin, a man who lives in the Parc Frontenac apartments with his partner and some sort of beagle-mix puppy. Kevin has just gotten his car stuck in the snow—but another man has just offered to help free him. The good samaritan pushes and unlodges the car, and Kevin is thankfully able to drive into his garage. But right as he gets the dog out of the car and just before he tells his partner, “There’s really some good in this world,” the good samaritan points a gun at him and demands his car. Disheartened at the state of humanity, Kevin obliges.

When Ben Fulton, the managing editor of this magazine, wakes up to take his seventeen-year-old daughter to school, he finds all of the wheels to his Subaru Legacy stolen, just bundles of snow holding the chassis upright. That morning, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reports that the city’s own Sam Altman is being sued by his estranged sister over alleged childhood sexual abuse. On its way from Columbia, the newspaper bearing the scandal passed through the western counties, where the highways are slow and crowded, where the corn stubble is suffocating in the snow.

Out west, both the big houses and the wood hovels resemble cottages; assorted horses idle in the fields of tundra; the farmers grow grey hair. Already the state roads that wind the limestone mountains are cleared and cold dead dry, just like the wind. Atop one great white hill sits a small herd of bison whose heavy huffs and puffs are unintelligible from the road below. On the porch of one trailer home, a dark blue and blood-red Trump flag is waving uncontrollably—and so is a war-torn, wind-torn, or simply just torn American flag.

Up in the clouds, a polar vortex from the Arctic is being pushed southward by movements of the Earth’s great wind streams. The storm’s eight inches of snow—more than a foot in some places—is replenishing the region’s aquifers, but all the salt on the streets is bad for the region’s streams. In St. Louis’s week of freezing temperatures, scientists at the Copernicus Society report that last year was the hottest on Earth’s record, while the local outfit of the National Weather Service says it was the second hottest on St. Louis’ record.

On the highways, the sun burns the colors off the cars, which are tufted with flat white mohawks or rather, frosted with blank buttercream. Hanley Road is dotted with potholes formed by the expansion of frozen water. Uncontrollably, the accumulation on the cars springs off and crashes to the ground in a million melting pieces, like glittering vanilla confetti.

Forest Park Parkway is driveable: At varying stretches, there are one, two, one-and-a-half, two, one, two, one-and-a-half lanes open. In the waiting room of a dentist’s office in Midtown, an old lady and five former presidents—including Trump and Obama, who are sitting together—watch a parade of seriously stomping military men, one of whom collapses in the cold, at Jimmy Carter’s funeral. The old lady stares intently up at the TV screen, at shots of earmuffed honor guardsmen, and at a history professor who—volume down—is whispering to a news anchor.

On the highways, the sun burns the colors off the cars, which are tufted with flat white mohawks or rather, frosted with blank buttercream. Hanley Road is dotted with potholes formed by the expansion of frozen water. Uncontrollably, the accumulation on the cars springs off and crashes to the ground in a million melting pieces, like glittering vanilla confetti.

Between University City and Olivette, the synagogues let out and the Sabbath begins. Boys in black and white dress clothes climb huge frozen piles as their families walk home in the street—along a singular vehicular path. Cars stumble along these set tracks, then slow for the people who stop and wait for them to pass. The sidewalks have been erased, and along the sides of the road, cars sit snowlocked. There is the feeling—car approaching—that as the Jewish families’ slacks press against the snow, there is nowhere left to go. The neighborhood looks completely congested; the place has been divinely entrapped.

At the zoo, a gaggle of penguins are led outdoors like POWs. Behind them, shooing them along, are men in matching khaki pants, heavy jackets, boots, and beanies. The penguins play between a few cement paths beside rocks graced with some remaining snow. Then they waddle back inside, the men close behind. Elsewhere, the zoo’s newborn baby elephant, Jet (who is the exact grey shade of a fighter plane) stomps on a miniature snowman and wiggles his trunk about its melting remains.

Fox 2’s recently retired news anchor, Elliott Davis—the “You Paid For It!” guy—is upset at Mayor Jones, who he says is unprepared and unwilling to provide warm shelter for St. Louis’s homeless population. The mayor banked on there being room in the city libraries—but all the libraries closed because of the snowstorm—and Davis is documenting volunteers who are helping homeless residents get through the nights below freezing. With the same cadence he used on Channel 2, Davis films himself in City Hall, in homeless shelters, and on the street, interviewing officials, advocates, and homeless people for his followers on Facebook. The retired anchor is practically running a one-man news station right from his mobile phone.

Streaking down the slope of Art Hill are bleach-blond paths trailing from the statue of King Louis IX to the frozen water basin below, where tots are sliding and skidding on the ice, worrying their parents. Tramping upward against the grade are children and grown-ups carrying the plastic and antique wooden vehicles which they again intend to descend.

Grinding through the Delmar Loop is a pick-up truck equipped with the Salt Dog PRO 2500. Filling the bed of the truck are fat sacks of light-brown-sugar-looking salt, which tink tink tink to the asphalt, bouncing upon the wheels of another vehicle whose expired temp tag flaps with almost the same frequency as the illuminated neon coat tail of the Magic Mini Golf man.

On a side street off Delmar—where the trash is not being picked up and the mail is not being delivered—a girl has gotten her sedan stuck at the entrance of a subdivision. When she begins to shovel around the car, she realizes that she has just locked her keys in the car. Hopelessly she tries to jimmy the doors of the sedan, but then an SUV full of women passes, and the women lend the girl some advice. Now a firetruck full of weary, middle-aged, varyingly virile men is on its way because the women told the girl to fabricate a kitten or a puppy or— better yet—a baby for the men to come and save. A young man passing by stops at the scene to shovel some snow before the firemen arrive and make him feel inferior. Anyway, he sighs that he is happy to be back in the West End; he lives in North County, where the gangbangers do not stop on account of the snow. He still hears shots as the night falls and the snow keeps on coming down.

Fox 2 News says that “disgruntled residents” are complaining about all of St. Louis’ unplowed streets. On and on the plows drive throughout the night, the city workers clearing snow in over-twelve-hours shifts, boxed inside these menacing, antennae-eyed, broad-faced trucks—these trucks with their dull yellow eyes, creepy-crawly rumbling roars, and behind them, that skeletal-sounding vomiting of sodium chloride. The county is understaffed by forty drivers. The right-hand lanes of most interstates are gone, covered in the snow that the plows just cleared from the middle lanes. That side-lying snow is constantly greying, browning, blackening—decaying into the city in which it fell.

The sky stays like this—awfully phosphorescent, like the constant bombardment of old European cities—until the blue returns late the next morning, when the roads are better, businesses reopen, and women stream into Lordo’s Diamonds.

A boy and a girl have just arrived at Clayton High School, and after braving the white expanse of the football field, they search in vain for a bracelet the girl lost the day before. The sun has long descended, and by now, the sky is slightly purple, a tad pink—blushing, albeit coldly. As the boy shovels around the soccer goal and the girl squats and digs with her gloved hands, children’s voices ricochet off the breeze, the trees, and the distant whirl of cars. The boy gets low to glide long, drawn-out pushes then stands up frustratedly and makes a few quick tosses; the girl rises and warms her hands with her breath. Love is the only force that could drive such a futile search.

Eastward, the pink deepens; westward, the ugly green-grey that will last throughout the night is spreading upwards, replacing the sun, toxically radiating off the Christmas lights below. The sky stays like this—awfully phosphorescent, like the constant bombardment of old European cities—until the blue returns late the next morning, when the roads are better, businesses reopen, and women stream into Lordo’s Diamonds.

Trish Scherer sells single-diamond earrings and a rainbow-sapphire bangle bracelet to the mostly-female shoppers who have gone stir crazy in their snow-capped homes. The women come in and immediately pace the aisles and probe the glass cases of jewels. Trish can tell there is no event, anniversary, or husband they are shopping for. She fits them for new jewelry, then realizes midday that she, too, has gone stir-crazy; she was not even scheduled to work.

Dogs sniff for mole tunnels in the backyards no one bothers to shovel; birds still chirp from the barren tops of trees, which glisten with twigs encased in glassy ice, and shatter like sticky toffee brittle. In some neighborhoods, the roads and paths are cleared by private hands and hired shovels. Inside the little wealthy villages of Ladue, which are enclosed from the street through winding lanes from which the chalets are all set back, you can see crisscrosses—faint but true—imprinted in the big white blank lawns. Deer, raccoons, and fathers in robes have been stepping through the snow down each house’s hill, on the edge of each house’s miniature forest.

The central corridor is somber, squalid, apocalyptic. One sullen-looking man is walking into the sun, the light reflecting and reverberating around his bundled-up body in the middle of the road. He is carrying two paper bags and all the city’s unheard hopes.

As the second round of snow stops falling, Stallone’s Formal Wear reopens, and in comes a dad in desperate need of a tuxedo for a father-daughter formal dance. Over the winter, Stallone’s survives on these all-girls Catholic school father-daughter dances—for which the fathers are supposed to sport the all-girls Catholic school’s colors—and all the all-girls Catholic schools in St. Louis are either green or red—and Cor Jesu is red—so Peter Rager gives the dad a red vest, red bow tie, and red pocket square.

At every high noon in this week of snow, the city streets start to bleed, to weep, to swell. Already in some places, St. Louis’ tear ducts have run dry, and its cheeks look exhausted from crying: the streets cracking, peeling, pent up with debility. Downtown looks as destitute as ever. Street corners are piled with giant, misshapen frozen cones. The bronze versions of Dred and Harriet Scott have had their feet stuck in a few inches of snow. The central corridor is somber, squalid, apocalyptic. One sullen-looking man is walking into the sun, the light reflecting and reverberating around his bundled-up body in the middle of the road. He is carrying two paper bags and all the city’s unheard hopes.

Over a year from now, when the airmen return from their deployment, this round of snow will be long, long gone. Ben Fulton will have replaced his Subaru’s tires, the farmers will have harvested another crop of corn, and the old lady in the dentist’s office will be due for another check-up. But the plow drivers will still be understaffed, the guns in North County will still be firing, and 2025 will probably be announced as the hottest year yet. This snow will darken into trash, sewage, and asphalt. It will melt and it will dry, and St. Louis will remain a city of diamonds, dead bodies, and green and red cummerbunds.