Remembering Ronald Fair

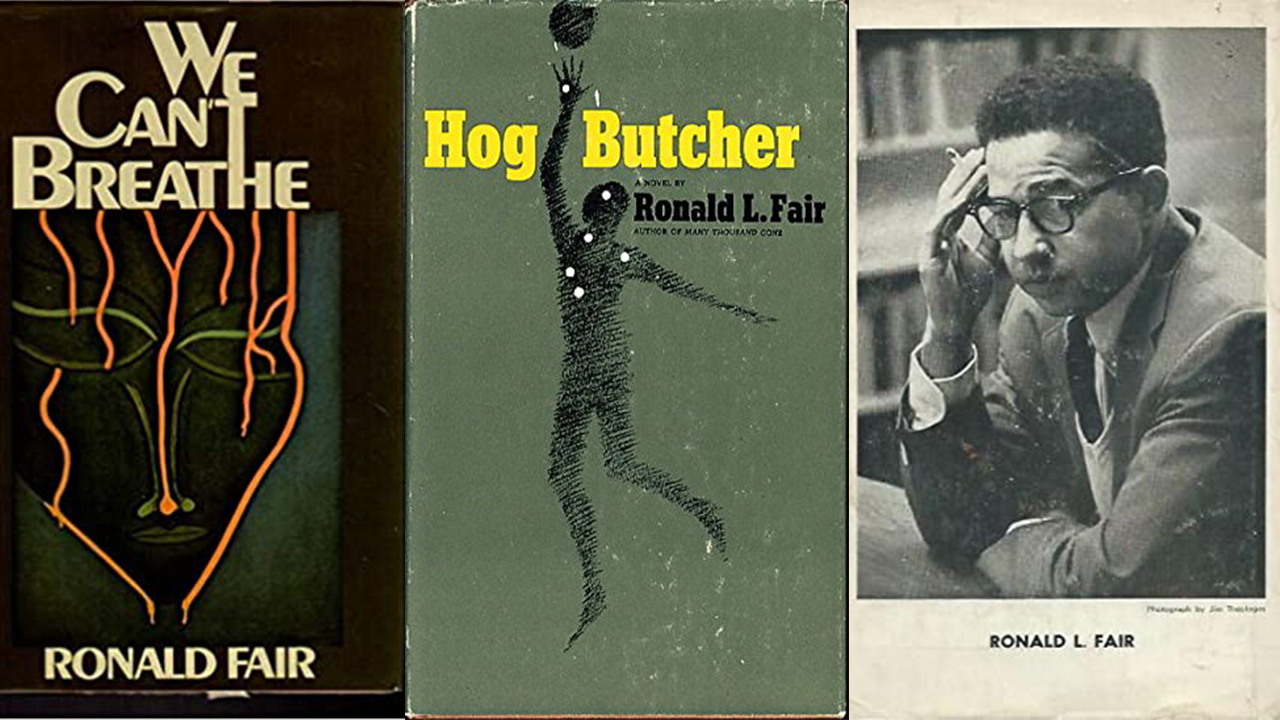

The Black expatriate’s novels, Hog Butcher and We Can’t Breathe, are more timely than ever.

By Cecil Brown

September 29, 2020

On his website, Richard Guzman wrote: “Another ‘I-Can’t-Breathe’ incident. I could not watch the video of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020. But I heard it while my wife described to me what she was seeing: a policeman with his knee on the neck of an already-subdued black man. It was on YouTube. A few will see these cops as heroes, but just as disturbing will be all those familiar gasps of disbelief: ‘How can this be happening in 2020?!’ —while virtually nothing else will be done.”

This incident took Mr. Guzman back to the phrase, “We Can’t Breathe,” and its author Ronald Fair.

It also brought me back, too. Back in 1966, when I was still a graduate student at the University of Chicago, I was walking out of my apartment on Kimball street and seeing some of our neighborhood kids—Black kids around nine or ten—dragging a television out of the back of a building. We had just had a riot in south Chicago and it was common to see Black kids looting.

I was on my way to meet Ronald Fair, the author of Hog Butcher, his novel, just published by Harcourt, Brace & World.

Hog Butcher was different from any novel I had ever read. His prose was exciting and infectious; you could not begin reading one sentence without reading the next sentence. But the most important thing was it was about police brutality. The story was set right in Chicago where we were having riots.

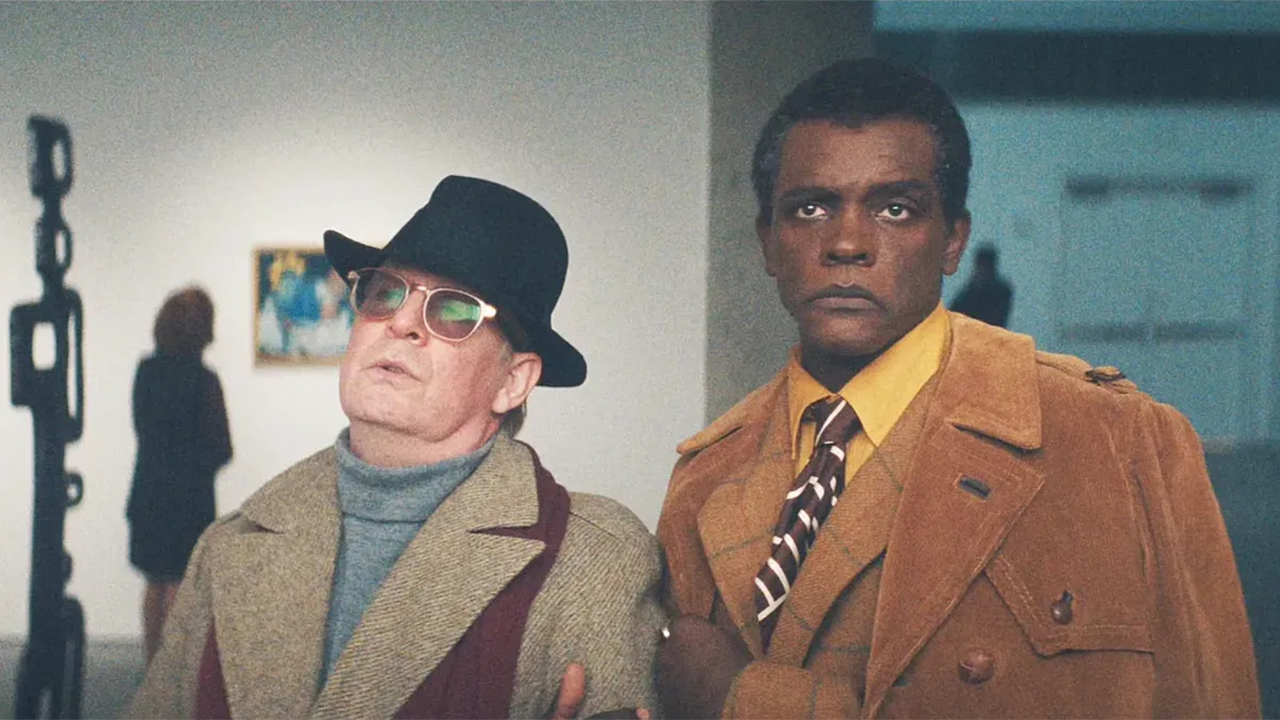

“Perhaps his most successful book, the novel Hog Butcher,” Mr. Guzman, wrote, “revolves around the shooting by Chicago police of an innocent black basketball star, Corn Bread.” This was the basis of the 1975 film Cornbread, Earl and Me, with a cast including Rosalind Cash and a very young Laurence Fishburne.

“Perhaps his most successful book, the novel Hog Butcher,” Mr. Guzman, wrote, “revolves around the shooting by Chicago police of an innocent black basketball star, Corn Bread.” This was the basis of the 1975 film Cornbread, Earl and Me, with a cast including Rosalind Cash and a very young Laurence Fishburne.

“Though some have commented on the novel’s humor and, in particular, on the energy and courage of the two adolescent protagonists through whom some of the action is seen, the novel is a sobering exploration of social class … and, of course, police violence.” What was impressive about the work was that it was a protest novel, immersive, and set in a place where the scene was actually unfolding.

I cannot remember how I got an interview with him, but I remember we were in a cafe and were smoking cigarettes and talking.

Ronald Fair was the first black man I ever met who had published a novel. I had seen his picture in The New York Times. I kept telling myself, “I want to do that.” I wanted to be a writer like him, but I did not know how. I had already begun my first novel, I think, but I was still looking for models I could imitate. I had not met Chester Himes or James Baldwin, and did not know that I ever would. I just took mental notes.

Ron told me he was born in Mississippi, but grew up in Chicago, always wanted to be a writer, went into the U.S. Navy for three years, was a court stenographer, so that he was free to write as he felt. (That impressed me because it was so hip; I mean, it was like, “What brother would think of doing that for a living?”)

“What are you going to do next,” I asked, as we were pushing back from the table.

“I’m leaving this motherfucking country—and I’m never coming back!”

I cannot remember my response, but I do remember that I was shocked. I was so unprepared that I did not ask why he was leaving—or where he was going.

Ronald Fair was the first black man I ever met who had published a novel. I had seen his picture in The New York Times. I kept telling myself, “I want to do that.” I wanted to be a writer like him, but I did not know how.

I had not expected to hear that, but I understood. I already knew that by choosing to be a Black writer, I was going be dealing with a loneliness I had already begun to feel. But what I was now realizing was that being a Black writer was also being abandoned. Just as I was creating a sense of fraternity with Ron, he was leaving—and never coming back.

In a few years, however, I had my own success—I had published my first novel to great acclaim. My name was in the newspapers and my novel was translated into several languages. When a foreign press published the novel, I would be invited to the city for a few weeks. For instance, when the French published it, I found myself in Paris hanging with other black literary expatriates. The journalists would ask me, what would you like to do? I would say, I want to find my friend Ron Fair. But no one knew where he was. Then, I asked Ted Jones, the surrealist poet, who knew where everybody was. “He’s in Zurich,” Ted told me. I did not know anything about Zurich, but I knew that if Ron was there, something hip was going on, and I should check it out. So, I went to Zurich. I actually found his number in the telephone book. But after calling many times calling and getting no answer, I lost the scent of the trail and went on to Copenhagen.

Many years passed. In 2010, I was asked by Northwestern Press, to write a preface to Hog Butcher. I had a chance to describe the impact the book had on me, to describe his mastery of stream-of-consciousness and the immersive nature of being there.

When the book was reissued with my introduction, I received a phone call from a young Black woman, who was Ron’s granddaughter.

She did not know much about her grandfather, did not even know that he was a writer.

I already knew that by choosing to be a Black writer, I was going be dealing with a loneliness I had already begun to feel. But what I was now realizing was that being a Black writer was also being abandoned. Just as I was creating a sense of fraternity with Ron, he was leaving—and never coming back.

Apparently, Ron had a wife and two children when he left, and according to his granddaughter, he did not come back. She had read Hog Butcher for the first time a few months earlier and now was so interested that she was flying to Finland to meet him.

What could I tell her about him? I told her that I had only met him once and that I had looked for him in Europe to no avail. We ended the conversation with my wishing her good luck and asking her to call me when she returned.

A week later I got a phone call. She had Ron Fair on Skype.

“Man, what happened to you?” I asked. “The last time I saw you, you said you were going to leave this m-f’ing country and you were never coming back!”

He said, “I remember that! I left and I never went back!”

“But why? You were so successful!”

Nineteen seventy-two saw the publication of the autobiographical novel We Can’t Breathe. For several years, aided by several writing grants, Fair traveled abroad, pursuing a writing life of great ambition. In the early seventies, critic Shane Stevens called him “one of the two best black writers in the country.” Yet this promise somehow never came to full fruition. In 1977 he relocated to Finland, dedicating himself more to sculpture than writing.

I asked him if he had ever lived in Zurich. “Oh, yeah, man. I was there for a few years!”

“Man, I was on your trail!”

“Being a Black writer was a dead end,” he said, laughing.

“But do you know about Eric Garner?”

“No, who is he?”

“He was screaming, ‘I can’t breathe!’ Just like your novel, We Can’t Breathe!”

It was a topic much in the news—again—with the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Dontre Hamilton in Milwaukee, Eric Garner in Staten Island, who kept gasping, “I CAN’T BREATHE.” Besides the many “non-suspicious” shootings by police and others of young Black men, there have been at least 29 decidedly suspicious shootings since 2012—sixteen of them occurring after Trayvon Martin.

“I didn’t know that,” he said. “That was why I left. Niggers don’t read.”

“Do you mean to say that if Blacks read your books, they would have been warned and could have prevented it?”

“That’s right.”

It became clear to me then that Ron believed African American literature played a crucial function in the survival of African American culture. Part of what made him lose his faith was the movie project that came out of Hog Butcher. When the producer read his screenplay, he disliked it so much that he had a heart attack. Ron regaled me with that on the Skype call. Then, he wrote another draft, and the dude had a second heart attack! Then, the producer sold the project to somebody else.

Still, the film was a success, and a break-through for Black cinema. After the disaster with the screenplay, Ron told me on Skype, he decided to give up on America. He turned his talent to sculpture. He had a successful opening show of his work in Helsinki, Finland.

A young Finnish art dealer liked his work and wanted to buy some pieces but his English was so bad that Ron could not understand him. Ron could not speak Finnish. They were stuck until a solution was found when the dealer called his sister, Hannele, who spoke better English.

It became clear to me then that Ron believed African American literature played a crucial function in the survival of African American culture. Part of what made him lose his faith was the movie project that came out of Hog Butcher.

Of course, when his sister Hannele showed up, she and Ron took “one look at each other and the rest is history,” he laughed. Rob showed me a picture of his five children and the beautiful Finnish woman who was his wife for some thirty years.

“Well, I said, what do you think of Black literature now?”

“I haven’t been following it,” he said.

“What about Henry Louis Gates [Jr.]?”

“I have never heard of him.”

He said goodbye and promised to stay in touch. That was in 2014 with the Eric Garner incident.

Now it is 2020.

It was not until a bit later that I heard George Floyd on television begging for his life. I grabbed my iPhone and searched for Ron’s number. After a day of digging through my electronic stuff, I found the essay that I had written about him. Back in 2014, I had sent this interview around to several magazines. I sent a copy to my friend Henry Louis Gates Jr. He was not so interested. At his suggestion, I sent it to Roots, only to have it rejected.

I finally found Ron’s email and shot him off another note: “Did he know that yet another Black man was crying out, ‘I can’t breathe!’”

Early the next morning, I was so happy to see that I had gotten a text from Ron.

But it was not what I expected.

Dear Cecil,

I’m sorry to tell you that Ron passed away February 2018. He was suffering from a cerebral hemorrhage. His memory started deteriorating in 2012 and he was having problems with the blood circulation in his brain. Finally, he could no longer stay home and he moved to a nursing home for about two months prior to his death.

As I read of the events taking place in the United States I can hear him saying: it is still the same. Nothing has changed since I left.

His books are still current. I have many of his unpublished manuscripts with me that deserve to be published. Just don’t have the means to get it done. Maybe you have some ideas …

With best regards

Hannele

I cried. I should have worked harder. I should have called Henry Louis Gates Jr. again and again. I should have demanded that the English department teach a class on his work! I should have tried harder. But then, Ron, you were right! Black people do not read. But White people do not read either.

I finally found Ron’s email and shot him off another note: “Did he know that yet another Black man was crying out, ‘I can’t breathe!’”

When Marshall McLuhan, the media analyst, was asked in his Playboy interview what would be the results of the clash between the oral cultures (represented by Black culture) and the digital age (represented by White culture), he said, “The Blacks might be exterminated.”

Nobody got upset when he said that, but now I can see that the knee on George Floyd’s neck is the Black man’s Kristallnacht.

What would Ron have said of George Floyd’s brutal execution? “As I read of the events taking place in the U.S.,” his widow wrote to me, “I can hear him saying: it is still the same. Nothing has changed since I left.”