Remembering Octavia E. Butler

A retrospective on the great science-fiction novelist.

August 28, 2020

The Crying Game

I feel no shame in admitting that, upon learning Octavia E. Butler had died on 24 February 2006, I wept.

This reaction is unusual, at least for me, because no matter how much I admire public figures, their passing rarely moves me to cry.

Yet Butler’s passing provoked fulsome tears as I read the many online obituaries, remembrances, and tributes to this marvelous American author that appeared, with metronomic regularity, throughout that day. And, make no mistake, Octavia E. Butler was among the greatest American authors of the twentieth century. The years since Butler’s passing have seen her work reclaimed by literary critics, scholars, and the reading public at large, but the fact remains: She was always terrific, even when too few people affirmed this judgment in the public square.

Some people, however, knew from the beginning. Specifically, the combative and innovative science-fiction (SF) writer Harlan Ellison knew. Ellison knew good writing when he saw it, as his editorship of the award-winning 1967 SF anthology Dangerous Visions attests. He helped launch Butler’s career by recognizing her talent when, in 1969, she enrolled in the Writers Guild of America’s (WGA’s) “Open Door” Workshop, a program run by Ellison that hoped to recruit talented African-American and Latinx screenwriters. Ellison recommended her for the 1971 Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop—a writers’ camp founded in 1968 at Clarion State College (now University), for aspiring-but-unpublished science-fiction-and-fantasy (SFF) authors—where Ellison was set to become a star lecturer, teacher, and all-around gadfly.

Ellison’s mentorship proved decisive for Butler’s authorial career, as he not only encouraged her literary ambitions but also purchased her short story “Childfinder” for publication in his anthology, The Last Dangerous Visions, originally scheduled for publication in 1973. Ellison—who died in 2018—never completed this work. Despite this setback, Butler sold another story, “Crossover,” in 1971, to the Clarion Journal, the workshop’s anthology publication. This beautifully rendered tale of a depressed, alcoholic woman living and working on Skid Row, with no hope for the future, features a concluding twist that calls her entire life into doubt by ending on a splendid final sentence that forces the reader to question everything that has come before, making “Crossover” not only an impressive debut for any author but also Butler’s first published work.

Then, despite the rush of excitement these victories provoked, Butler did not sell another word for five years.

California Dreaming

Octavia Estelle Butler, for the uninitiated, was born on 22 June 1947 in Pasadena, California, to her loving, but strict, Baptist mother, Octavia M. Butler. Estelle’s father, Laurice Butler, was a shoeshine man who died when she was a toddler, leaving Butler’s mother to raise her precocious, studious daughter alone. Working as a domestic servant in the homes of Pasadena’s white households earned Butler’s mother enough to ensure that Estelle received everything she needed. Times were so tight that Estelle’s mother would take home every book she could find—including volumes that her bosses threw into the trash—for her daughter to read.

One of the most heartbreaking anecdotes Butler ever told about her childhood involves her adult embarrassment, even shame, at remembering how, as a youngster, Butler felt humiliated by what she took to be her mother’s timidity in the face of racism. As Butler told Charles H. Rowell, editor of Callaloo: A Journal of African Diaspora Arts and Letters, during a 1997 interview, Octavia M.’s white employers would talk about their Black maid as if she were not in the same room with them, but Butler’s mother never, at least in Estelle’s memory, protested:

Sometimes I was able to go inside and hear people talk about or to my mother in ways that were obviously disrespectful. As a child I did not blame them for their disgusting behavior, but I blamed my mother for taking it. I didn’t really understand. This is something I carried with me for quite a while, as she entered back doors, and as she went deaf at appropriate times. If she had heard more, she would have had to react to it, you know. The usual. And as I got older, I realized that this is what kept me fed, and this is what kept a roof over my head. This is when I started to pay attention to what my mother and even more my grandmother and my poor great-grandmother, who died as a very young woman giving birth to my grandmother, what they all went through.1

This account of Butler coming to understand how resilient her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother were in their everyday lives helps explain why her writing includes such sensitive portraits of oppressed and marginalized people (and not just people, but also extraterrestrials).

Butler profited from her mother’s example in other ways. Octavia M. remained sensitive about being pulled out of school at ten years old when, while living in rural Louisiana at the height of Jim Crow segregation, she went to work to help her family’s precarious finances. Butler’s mother consequently stressed the importance of education, so Estelle became a voracious reader, both in response to her mother’s preferences and to stave off the loneliness Estelle experienced during her youth. Despite these hardships, Butler knew she wanted to become a working author when, at twelve years old, she saw on television the 1954 SF movie Devil Girl from Mars, thinking to herself, as many of this cornball film’s audience members must have, “I can do better than that!”2 Except that Butler, unlike everyone else, actually did so, enduring years of privation in her quest to publish her work, and, in the process, becoming, in 1995, the first American SFF novelist to receive a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation fellowship, then and now known as the “genius grant.”

Anyone who doubts Butler’s genius should pick up the first Butler novel or short-story collection at hand and begin reading. You will be hooked, not merely by Butler’s honed-to-perfection prose, but by her fiction’s uncanny ability to alter perspectives so gradually that, before realizing it, you are enmeshed in invented landscapes so satisfyingly well-imagined, so scrupulously thought-out, so remarkably detailed, and so painstakingly real (even when set on other planets or in the far future) that they never let you go, certainly not between sittings, and not even when you finish. Butler’s premises, plots, characters, and imagery will stay with you for years or, as in my case, decades. You never quite stop thinking about a Butler story because no one else has ever made you think about the past, the present, and the future as she does.

You never quite stop thinking about a Butler story because no one else has ever made you think about the past, the present, and the future as she does.

My advice is always to begin at the beginning, with “Crossover,” before chronologically marching through Butler’s bibliography. Yet I rarely take this advice, for whenever I teach Butler’s fiction (meaning, every semester), I begin with her Hugo- and Nebula-award-winning novella Bloodchild. This tale of Gan, a boy living on an extrasolar planet whose indigenous dominant species, the Tlic, confine all human beings to an area called “the Preserve,” always shatters my students’ expectations about what science fiction is, what it can be, and even what it should be.

The premise? Gan and his family (his mother Lien, his older brother Qui, and his younger sister Xuan Hoa) live in the Preserve under the protection of T’Gatoi, the Tlic government representative who helped found this fenced- and walled-off area. Gan and his relatives, forbidden by Tlic law to possess firearms, are descendants of the first human visitors to this unnamed planet, living several generations after their human ancestors—known as Terrans—arrived on the Tlic homeworld as refugees from slavery and oppression on Earth. This complicated history makes Bloodchild a far subtler story than the run-of-the-mill coming-of-age tale it may first appear. As if emphasizing this initial impression, Butler begins Bloodchild with Gan, the novella’s first-person narrator, announcing in its opening line, “My last night of childhood began with a visit home.”3 What could be more conventional than this declaration, which promises readers that a standard-issue American bildungsroman awaits? Yet Butler constructs these expectations only to demolish them in the next sentence: “T’Gatoi’s sister had given us two sterile eggs.”4 This character’s unfamiliar name—so alien that at least three possible pronunciations suggest themselves—and the reference to sterile eggs are the first clues that Butler weaves a more knotted narrative skein than readers might expect.

Bloodchild, indeed, slowly reveals that Gan must choose whether or not to become the host for T’Gatoi’s offspring, which will be implanted into his blood-rich body as small maggots that will grow into large grubs, after which T’Gatoi will remove them in a surgical procedure similar to a Caesarian section. The eggs that the Tlic give to their Terran “guests” are sterile only in the sense that they preserve human beings far beyond their natural lifespans so that, by remaining sexually vital, the men serve as hosts for Tlic young while the women ensure that the Terran population survives. This relationship does not strike Gan as strange, or even noteworthy, until he witnesses a man named Bram Lomas in terrible distress because the Tlic grubs implanted in his body begin eating their way out of his flesh, forcing T’Gatoi to cut them from Lomas in an emergency procedure that Gan witnesses.

Gan, disgusted by the sight of Lomas sliced open by T’Gatoi’s claws, realizes just how different she and all Tlic are. Bloochild variously describes T’Gatoi as a large creature with “yellow eyes,”5 “a long, velvet underside”6 whose “three meters of body … had bones—ribs, a long spine, a skull, four sets of limb bones per segment,”7 and a tail that “was an efficient weapon whether she exposed the sting or not”8 to suggest that the Tlic are a giant combination of mammal, centipede, and scorpion whose reproductive practices are as alien as their culture. Butler eschews traditional exposition in this novella, instead parceling out information in short passages of narration and dialogue that, by Bloodchild’s conclusion, becomes vividly hallucinatory.

Bloodchild, therefore, reverses American and British science fiction’s long history of colonialist adventure, imperialist violence, and political invasion by inverting this plot’s usual tropes. The novella’s human characters are the invading aliens, not the victims, and their arrival upon this extraterrestrial planet provokes a battle for domination that the Terrans lose. They find themselves forced to co-exist, as peacefully as possible, with an alien species that demands a most unusual accommodation: human men must agree to assist the Tlic in reproducing (and thereby strengthening) themselves.

Bloodchild reverses American and British science fiction’s long history of colonialist adventure, imperialist violence, and political invasion by inverting this plot’s usual tropes.

That Butler chooses to tell this story through the eyes of a young boy who must decide whether or not to become pregnant by his extraterrestrial caretaker is so subversive that it splinters every notion about American science fiction (as a corpus of slam-bang adventures to the stars) that anyone ever held. Bloodchild, instead, unfolds its idiosyncratic account of a young boy’s first sexual experience by shifting, reversing, and imploding traditional gender stereotypes, so much so that the following passage never fails to make my students uncomfortable when read aloud:

Yet I [Gan] undressed and lay down beside her [T’Gatoi]. I knew what to do, what to expect. I had been told all my life. I felt the familiar sting, narcotic, mildly pleasant. Then the blind probing of her ovipositor. The puncture was painless, easy. So easy going in. She undulated slowly against me, her muscles forcing the egg from her body into mine. I held on to a pair of her limbs until I remembered Lomas holding her that way. Then I let go, moved inadvertently, and hurt her. She gave a low cry of pain and I expected to be caged at once within her limbs. When I wasn’t, I held on to her again, feeling oddly ashamed.9

These seemingly unadorned sentences construct a passage so affecting in its honesty that Gan’s experience becomes unforgettable in effect. Even better, Butler acknowledges just how awkward and faintly ridiculous first sexual encounters are. Gan’s shame transforms this scene into a brutally honest meditation about sex, desire, and affection that depicts a human boy being penetrated by a scorpion-like creature on an alien planet in the future. Each word complements the next in a bravura narrative display that is as outrageous as it is casual.

This passage’s economy, fluency, and sensitivity always amaze me. Who but Butler could write one of the best sex scenes in American literature about a boy becoming a man by sleeping with an insect-like extraterrestrial, yet keep it grounded in resonant physical, psychological, and emotional detail?

That is the brilliance that Ellison recognized all those years ago. Butler graces her readers with such flair in every piece she ever published.

Time Out

Bloodchild is much more than a humdrum narrative about colonialist violence and imperialist aggression, but specifically encodes parallels to both American slavery and Native American oppression into its narrative.

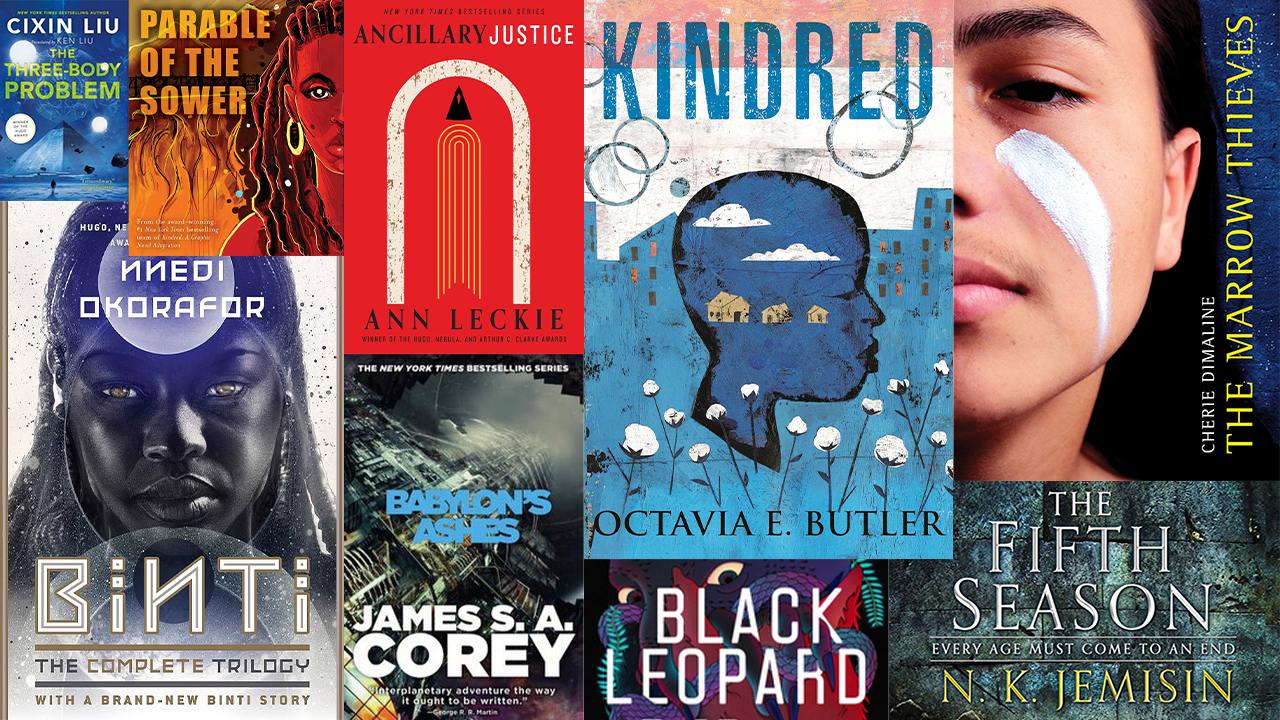

This declaration brings us, inevitably, to Butler’s 1979 masterpiece: her fourth novel, simply titled Kindred. Again, the premise is irresistibly disturbing: an African-American writer named Edana Franklin (Dana, for short), while moving into her new Los Angeles house with her new Caucasian husband, Kevin, on her twenty-sixth birthday (9 June 1976), experiences sudden dizziness, only to find herself mysteriously transported in time and space to the antebellum plantation of slave owner Tom Weylin, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where she sees Tom’s son, the child Rufus Weylin, drowning in a river. Dana saves Rufus from the water right before Tom points a rifle in Dana’s face and cocks the trigger. Dana, frightened for her life, becomes dizzy again, then finds herself back in her 1976 home, with the perplexed Kevin telling her she disappeared for a few seconds despite the fact that, from Dana’s perspective, several minutes have elapsed. Thus begins a pattern: whenever Rufus finds himself in mortal danger, Dana is pulled from 1976 California back to the Weylin plantation in whichever year Rufus requires assistance (1815, then 1819, then 1824, but always moving forward in time). Dana continues to save the progressively crude and cruel Rufus from disaster because he will one day marry Dana’s ancestor Alice Greenwood and, in 1831, father a girl named Hagar, Dana’s great-great grandmother.

This insidious, ingenious plot condemns Dana, during her trips to antebellum Maryland, to live as a slave on the Weylin plantation despite the feminist consciousness and personal independence she has developed during her 1976 life. It also forces Kindred’s readers to reckon with the violence, terror, and grinding oppression of American slavery, as well as the strength, endurance, and dignity of its enslaved characters, whom Butler develops in such detail that they remain indelible after even a single reading. Butler, with Kindred, writes a terrific example of what Bernard W. Bell, in his noteworthy 1987 book The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition, calls the “neoslave narrative,”10 a present-day fictional reconstruction of “the peculiar institution” of American chattel bondage that, at its best, helps readers understand the experience of American slaves in ways that approach, and occasionally surpass, the actual slave narratives of writers such as Harriet Tubman, Harriet Jacobs, Mary Prince, Olaudah Equiano, Solomon Northup, and, most famously, Frederick Douglass.

Butler told Lisa See in a 1993 Publisher’s Weekly interview that the inspiration for Kindred came from her days at Pasadena City College, when a friend and fellow student involved in the Black Power Movement “who could recite history but didn’t feel it . . . said, ‘I wish I could kill all these old black people who are holding us back, but I’d have to start with my own parents.’ Well, it’s easy to fight back when it’s not your neck on the line.”

Kindred’s power emanates from its fantastic premise, in which a twentieth-century Black woman involved in an interracial marriage must come to terms with slavery in the most literal manner. Dana must learn to live as a slave when she returns to antebellum Maryland for increasingly longer stretches of time, with Butler powerfully depicting the psychological, physical, and spiritual compromises that this journey forces onto her protagonist, who nonetheless refuses to be objectified by any member of the Weylin family despite realizing that, in order to survive, she cannot resist her bondage or her bondsmen in the forthright manner she would prefer. Dana cannot simply attack, injure, or kill the white men and women whom she encounters, for she soon recognizes how pervasive is the generational system of racist terrorism that slavery was, a truth that Kindred depicts so well that certain audience members (including some of my own students) vow never to read it again.

Butler told Lisa See in a 1993 Publisher’s Weekly interview that the inspiration for Kindred came from her days at Pasadena City College, when a friend and fellow student involved in the Black Power Movement “who could recite history but didn’t feel it . . . said, ‘I wish I could kill all these old black people who are holding us back, but I’d have to start with my own parents.’ Well, it’s easy to fight back when it’s not your neck on the line.”11 Mentioning to Charles H. Rowell during their 1997 Callaloo conversation that “I’ve carried that comment with me for thirty years,”12 Butler’s empathy for her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother contradicted her friend’s attitude so forcefully that she wished one day to publish a book refuting his wrongheaded perspective: “So I wanted to write a novel that would make others feel the history: the pain and fear that black people had to live through in order to endure.”13

On this score, Kindred remains a smashing success, a signature contribution to American letters, and, yes, a masterpiece no less praiseworthy than Toni Morrison’s famed novel Beloved. Harlan Ellison, when asked to write a blurb for Butler’s fourth novel, lauds his protégé’s work by offering this panegyric, as fulsome as any praise for Morrison’s novel:

Kindred is a story that hurts: I take that to be the surest indicator of genuine Art. It is an important novel, filled with powerful human insight and the shocking impact of the most commonplace experiences viewed in a new way, and it demands that once begun, the reader continue till it has done its work on the heart and mind and soul.14

Nobody Does It Better

Kindred, exceptional as it is, should not obscure the eleven other novels that Butler published during her lifetime or suggest that her primary fictional interest lies in African-American bondage. Butler avoided the literary trap so frequently set for Black American authors—expected as they are by the literary establishment to address racism and its infinite permutations to the near-exclusion of other themes, ideas, and experiences—by “writing herself in”: with the exceptions of Samuel R. Delany’s oeuvre and Star Trek’s multicultural future society (Butler was a fan of Gene Roddenberry’s franchise until her dying day), she failed to see herself in the SFF novels and short stories she so avidly consumed in her youth or in the SFF movies and television programs that she watched.

Twentieth-century SFF fiction’s frequently tin-eared manner of representing race, ethnicity, and diversity—by transforming extraterrestrial (or other fantastic) beings into literary symbols of non-white peoples so that white authors can make jejune points about racism’s insidious effects, rather than directly placing non-white characters and their complexities onto page and screen—led Butler, even as a youngster, to notice these genres’ exclusivity. She rebelled against their myopia, telling the New York Times in a 2000 interview, “When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read. The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway. I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.”15

Butler, by this reckoning, was triumphant from the start, with her first published novel, 1976’s Patternmaster, inaugurating the Patternist series. Pattenmaster, although released first, comes last within this series’s fictional chronology, which sees human beings divided into three groups who vie for power across an immense time span, from Ancient Egypt to the far future.

Butler develops this remarkably detailed, secret, and alternate history of Earth across four more novels (1977’s Mind of My Mind, 1978’s Survivor, 1980’s Wild Seed, and 1984’s Clay’s Ark), but her signature innovation is having Patternist society’s two immortal, founding figures—Doro (who can not only transfer his consciousness from person to person but who begins the selective-breeding program that creates the Pattern after centuries of effort) and Anyanwu (a woman with such precise control of her body that she can shift into nearly any shape, allowing her to live as different persons throughout human history)—be born in Africa millennia before Patternmaster begins.

After Kindred, however, Butler’s best-known work is a three-volume series now called Lilith’s Brood, but known as “Xenogenesis” when first published. Dawn (1987), Adulthood Rites (1988), and Imago (1989) tell the epoch-spanning story of humanity’s recovery from nuclear apocalypse thanks to the intervention of the extraterrestrial Oankali, a species of galactic gene traders who come upon Earth after a late-twentieth-century nuclear war has devastated the planet. Dawn begins 250 years later, when the Oankali revive protagonist Lilith Iyapo, an African-American woman, aboard their living spacecraft high in Earth’s orbit. The Oankali’s physical appearance initially repulses Lilith, who must grow accustomed to the mobile sensory tentacles covering their humanoid bodies. The Oankali’s price for saving a few thousand human beings and restoring the Earth’s surface to pristine condition is twofold: Lilith must begin training groups of human survivors to return to Earth to reclaim the planet while the Oankali harvest human genetic material for their species’ third sex, the Ooloi, whose bodies are natural gene-splicing laboratories that combine, manipulate, and refine radically different DNA strands as easily as human bodies produce antigens to fight disease.

Butler is at her best in the Parable novels, which at the time of their release read like horrific cautionary tales but now resemble forecasts falling on so many deaf ears that Butler has become an American Cassandra, shouting truth into void, never to be believed until too much time has passed.

The Oankali are fascinated by human cancers, which they genetically modify to become agents of biological regeneration. Wounds heal, limbs regrow, and lives extend far past their normal limit, both for Lilith and for the human-Oankali offspring that the Ooloi begin constructing. Although shades of Bloodchild stalk this premise, Butler weaves numerous biological, ethical, and philosophical conundrums into Lilith’s Brood, yet populates it with so many memorable characters and so much fine writing that this trilogy provokes deep thought while never reading like a treatise.

Lilith Iyapo is yet another fictional avatar of Octavia E. Butler, meaning a character of marvelous flaws and remarkable insight, who extends her creator’s career-long project of writing Black women into science fiction’s notorious good-ole-boys club. So is Lauren Oya Olamina, the central figure of Butler’s perceptive Parable duology (1993’s Parable of the Sower and 1998’s Parable of the Talents), who decides to create an entirely new religion called Earthseed to counteract the dismal realities of living in late-twentieth-century America, where global warming has provoked economic crises so severe that some citizens barricade themselves into gated communities to avoid roving gangs of desperate marauders who steal whatever they can to survive in a landscape so terrible that the word dystopian hardly does it justice.

Butler is at her best in the Parable novels, which at the time of their release read like horrific cautionary tales but now resemble forecasts falling on so many deaf ears that Butler has become an American Cassandra, shouting truth into void, never to be believed until too much time has passed.

In remarks delivered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on 19 February 1998, Butler said about Parable of the Sower, “This was not a book about prophecy; this was an if-this-goes-on story. This was a cautionary tale, although people have told me it was prophecy. All I have to say to that is ‘I certainly hope not.’”16

Sometimes even prophets (and geniuses) do not relish getting it right.

The End Is the Beginning

Butler’s final novel, 2005’s Fledgling, began as the Parable series’ third projected volume, tentatively titled Parable of the Trickster. According to Gerry Canavan, in his invaluable book Octavia E. Butler (significantly, the only scholarly biography of Butler yet published), she began this novel so many times that, when he first encountered its various drafts in Butler’s collected papers at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, Canavan was bowled over by what he discovered:

What I found were dozens upon dozens of false starts for the novel, some petering out after twenty or thirty pages, others after just two or three; this cycle of narrative failure is recorded over hundreds of pages of discarded drafts. Frustrated by writer’s block, frustrated by blood pressure medication that she felt inhibited her creativity and vitality, and frustrated by the sense that she had no story for Trickster, only a “situation,” Butler started and stopped the novel over and over again from 1989 until her death, never getting far from the beginning.19

Butler eventually moved to Fledgling, which, if not the best vampire novel ever written, occupies the highest echelon of this ever-expanding genre.

Fledgling begins much as Dawn does, when protagonist Shori awakens from unconsciousness alone, injured, and incapable of remembering exactly what happened to her. Suffering terrible burns and extreme trauma to her skull, the out-of-her-mind Shori senses an approaching creature and instinctively kills what turns out to be a human being. Surprised by her own strength and the fact that drinking this person’s blood helps her begin healing more quickly than expected, Shori eventually pieces together that she is a member of the Ina, a long-lived nocturnal species that resemble human beings, but that must drink human blood to sustain themselves. Doing so, in one of Butler’s cleverest amendments to traditional vampire lore, provides symbiotic relief to the human beings with whom Shori and all Ina bond. These symbionts, as regular people are called, receive boosted immune systems and longer lives from the venom transferred to them by the Ina’s bite.

Butler develops detailed biological, cultural, and political backgrounds for the Ina, as well as their contested relationships with regular human beings, that synthesize so many themes from her previous work that Fledgling offers a terrific précis of Butler’s entire authorial career.

Fledgling offers scientific explanations for the vampire novel’s supernatural trappings while also plumbing the racist predilections of Ina society. Butler develops detailed biological, cultural, and political backgrounds for the Ina, as well as their contested relationships with regular human beings, that synthesize so many themes from her previous work that Fledgling offers a terrific précis of Butler’s entire authorial career.

Canavan’s biography reveals that alternate versions of Fledgling, as well as many other Butler novels and short stories, reside in her collected papers at Huntington, so the possibility that Butler’s estate will authorize alternate editions of her existing work remains a tantalizing possibility. Who among us would turn down variant printings of our favorite Butler works, or the even more enticing potential for unearthing brand-new works from the Huntington’s Butler collection? Such a prospect, after all, has already come to fruition: two additional stories written during the 1970s—the novella A Necessary Being (a precursor to Butler’s third novel, Survivor) and the long-awaited “Childfinder” (salvaged from the literary wreck of Harlan Ellison’s The Last Dangerous Visions anthology)—found their way into 2014’s Unexpected Stories, available then and now only as an e-book. Reading these works eight years after Butler’s untimely passing provoked more tears. They are so good that Walter Mosley pegs them exactly, in his foreword, as “a kind of poetry and revivification … the hallmarks of our lost sister. Reading these tales is like looking at a photograph of a child whom you only knew as an adult. In her eyes you can see the woman that you came to know much later—a face, not yet fully formed, that contains the promise of something that is now a part of you: the welcomed surprise of recognition in innocent eyes.”18

Mosley eloquently expresses what Robert Crossley observes in his introductory essay to Beacon Press’s 1988 reissued edition of Kindred: “Like all good works of fiction, it lies like the truth.”19 Hear hear, I say, since Crossley’s judgment describes all of Butler’s writing, from “Crossover” in 1971 to Fledgling in 2005, and all points in between.

And so, when realizing anew how incalculable a loss Butler’s death means for American letters and American culture—indeed, for the entire American republic, which can no longer benefit from her wisdom, her compassion, and her wit—to think about what might have been, to speculate about the remarkable novels Butler would have written had she lived, to realize that her voice is silenced forever, to know that we shall never again hear her wonderful laughter, to recognize how profoundly Butler has affected the way her readers perceive the world, to understand how great a gift her fiction is to the project of deepening our own humanity, to miss Octavia E. Butler in all the ways that we can miss a person we never met in the flesh, to lose this artist who has so immeasurably enriched—and continues to enrich—our lives, what else is left to say?

Once again, I weep.

1 Charles H. Rowell, “An Interview with Octavia E. Butler,” Conversations with Octavia Butler, edited by Conseula Francis, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, pp. 78-79. Readers may also find Rowell’s interview with Butler in Callaloo, volume 20, number 1, Winter 1997, pp. 47-66.

2 Interested readers may view this 80-minute film on the website Vimeo to determine for themselves how accurate Butler’s judgment was: https://vimeo.com/20281651.

3 Octavia E. Butler, Bloodchild, Bloodchild and Other Stories, 2nd ed., Seven Stories Press, 2005, p. 3.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., 13.

6 Ibid., 3.

7 Ibid., 9.

8 Ibid., 11.

9 Ibid., 27.

10 Bernard W. Bell, The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition, University of Massachusetts Press, 1987, p. 246.

11 Lisa See, “PW Interviews: Octavia E. Butler,” Conversations with Octavia Butler, edited by Conseula Francis, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, 40. See’s interview with Butler first appeared in Publisher’s Weekly, 13 December 1993, pp. 50-51.

12 Rowell, Conversation with Octavia Butler 79.

13 See, Conversations with Octavia Butler 40.

14 Harlan Ellison, Kindred cover, Beacon Press, 1998. Ellison’s blurb first appeared on this reissued edition of Kindred and has appeared on the cover (or in the opening pages) of most editions published since. Ellison seems to have prepared this appreciation specifically for later reprints of Kindred since his collected nonfiction writings omit it.

For Ellison’s full blurb, please see the website LitLovers’s Kindred page at:

https://www.litlovers.com/reading-guides/13-fiction/10066-kindred-butler?start=2.

15 Margalit Fox, “Octavia E. Butler, Science Fiction Writer, Dies at 58,” New York Times, 1 March 2006, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/01/books/octavia-e-butler-science-fiction-writer-dies-at-58.html.

16 Octavia E. Butler, “Devil Girl from Mars: Why I Write Science Fiction,” public address, 19 February 1998, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, http://web.mit.edu/m-i-t/articles/butler_talk_index.html.

17 Gerry Canavan, Octavia E. Butler, Modern Masters of Science Fiction, University of Illinois Press, 2016, p. 144.

18 Walter Mosley, “Foreword,” Unexpected Stories by Octavia E. Butler, Open Road Integrated Media, e-book.

19 Robert Crossley, “Introduction,” Kindred by Octavia E. Butler, 1979, Beacon Press, 1988, p. ix.