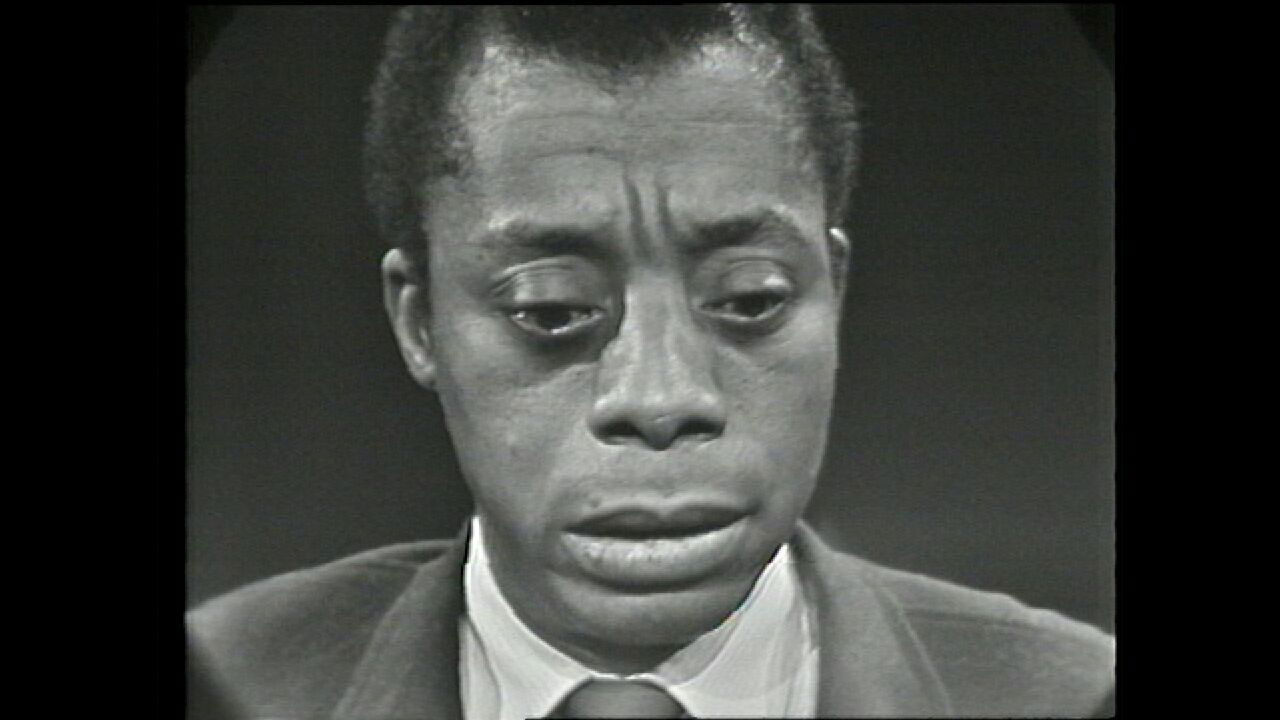

I came to know James Baldwin, the essayist, after I fell in love with Baldwin, the novelist. In discovering his writing anew, his critiques of American life moved me in new ways. All too often academics and intellectuals must don the cloak of professionalism that, ironically, restricts honest speech rather than providing a platform for it. Opportunities to speak openly, plainly, and personally about the social world are hard to come by. Baldwin inspired me to lay down the cloak from time to time. His reflections on educational inequities—which placed the family front and center—serve as backdrop to this essay, written by an uncle and a sociologist as a meditation on inequality in America.

Reflecting on blacks’ position in the world, Baldwin was critical— even cynical—but never defeatist. He knew, like W.E.B. Du Bois, what it meant to “grasp a hope, not hopeless, but unhopeful.”1 Baldwin reminded us of the greater angels of America’s nature even as he chronicled its devilish, deceitful ways. He wrote of equality, justice, and the legacy of their absence. Writing to his nephew, and to us all, he deplored how “this innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish.”2 Southern trees still bear strange fruit and American soil is laden with weeds that strangle life out of communities.3 The Fire Next Time shows how the personal is inherently political, and the political is inherently personal.

Baldwin’s essays on the intersection of race, inequality, and education, such as “A Fly in Buttermilk” and “Nobody Knows My Name,” cut deeper still. Through them Baldwin spoke, not of the curiosity or smarts that blacks must have when they enter the classroom. Rather, he lamented the bravery blacks must possess to defy the odds against them, to withstand social scars and psychological pains they inherited along the way. His trips down South after desegregation, punctuated by interviews with youth who entered formerly white-only schools and conversations with the principals who managed them, were chilling. His words captured the callous disregard for black lives that scarred (and still scars) the nation. And all the while, blacks were to be like Jesus upon the cross and offer, as Scripture tells us, not a mumbling word.

Opportunities to speak openly, plainly, and personally about the social world are hard to come by. Baldwin inspired me to lay down the cloak from time to time.

In the midst of documenting the crippling injustices of his day, family, whether his own or another’s, factual or fictive, remained a constant theme in his critiques of social life in America. Baldwin’s closeness to his nephew, and the hope and great sadness housed within that bond, reminded me of my connection to my youngest niece. Both bookish. Both black. Both broke. We shared a curiosity that leads not only to asking questions, but also to finding their answers. We both loved a good laugh, whether at others or at ourselves. The parallels forced me to think of what I have endured to make it through segregated, poor neighborhoods of Miami and privileged, white communities I found myself in at Amherst College and Harvard University with an eye toward ensuring that my niece’s journey to college was less uncertain, less bumpy, less swayed by poverty’s undercurrents.

A choice

On the eve of her eleventh birthday, I owed my niece an explanation that she never demanded I give. I owed her answers to questions she might not know how to put into words quite yet. For she never asked why we took her out of one elementary school and put her in another one, this time a private one. She never wondered, at least not to me, why we uprooted her from friends and teachers—some teachers who had taught me, albeit under better circumstances, when I was her age—and placed her in a school located in a part of town where we were not always welcomed and our presence often drew prolonged looks. But I grappled with this question each morning as she crisscrossed boundaries en route to school.

I begged my brother to put my niece in a private school. To help make the decision easier, I offered to foot the tuition bill while living on a graduate student’s stipend. I did this because, in short, leaving home permitted me a peek from behind the veil.4 As Greenwich Village illuminated a new world and novel way of life for Baldwin, college simultaneously served not only as my escape from more limited perspectives of an isolated, segregated community, but also my introduction to the social forces that made it so.

And now I am a sociologist. And a sociologist of inequality and education, no less. My own research on how poverty shapes poor students’ pathways through college opened my eyes even more. I witnessed how the Doubly Disadvantaged—poor students who attended local, distressed high schools—and the Privileged Poor—students who are equally poor, but who attended elite boarding, day, and preparatory schools—shared similar origins, but had increasingly divergent lives en route to college.5 The Doubly Disadvantaged’s local schools were under-resourced, disordered, and in general disarray. They were places where fights were more common than exams. The Privileged Poor attended schools that were the mirror opposite of their poor peers’. They ventured to places that presidents, senators, and even kings deem worthy of their children.6 In college, after four years of life in these disparate places, the Doubly Disadvantaged felt like outsiders in a strange land, while the Privileged Poor felt more like guests at a familiar place. In their divergent experiences, I saw present-day manifestations of historical legacies, exclusion, and indifference to racial subordination. Each day, it seems, newly enacted policies continue to renege on the social contract that the Supreme Court tenuously renewed in Brown v Board of Education. Sometimes it feels as if “all deliberate speed” really meant, means, and will continue to mean, “take thy time.”

Baldwin’s closeness to his nephew, and the hope and great sadness housed within that bond, reminded me of my connection to my youngest niece. Both bookish. Both black. Both broke. We shared a curiosity that leads not only to asking questions, but also to finding their answers.

When will we break this cycle of hurt and neglect? Times have, mercifully, changed for the better, but the march is far from over. An odyssey, not a sprint. But when I read, for hours at a time, for days on end, about how entrenched inequalities block mobility and limit avenues to a better life fall disproportionately on black and brown communities, a kind of haze settled over me. An empty heaviness lingers in the pit of my stomach. Incarcerated at higher rates, historically and today.7 Educated at lower rates at lower-rate schools, historically and today.8 I tried to escape by returning to fiction, from Another Country to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows and everything in between. A kind of literary safe space, if you will. But Baldwin had another lesson for me. It was as if I heard him say, with a knowing, piercing look on his face, “havens are high-priced [for] the price exacted of the haven-dweller is that he contrives to delude himself into believing that he has found a haven.”9 More than denouncing the act of hiding oneself from the world, Baldwin was prescriptive in how one should engage the world: for a writer, “his object is himself and the world and it requires every ounce of stamina he can summon to attempt to look on himself and the world as they are.”10 As a sociologist, I believed the same to be true.

Reality hit me every morning when I called my niece. At 7:30 am, when my mother picked her up, I thought about how studying poverty and its deleterious effects was not simply work, as it was for many of my peers; it was my life. Growing up, I remember one time doing homework by candlelight. I did so not to be romantic; rather, my motivation was more practical. Even with herculean efforts to give us what we needed, my mother faced a reality that many poor parents know all too well: that sometimes there is more month at the end of the money.11 Homework needed to be completed after sunset so candles lit the way until power was restored.

I quickly learned what it meant to live a life of maybes. Maybe we can do this. Maybe we cannot. This is not to say that life was drab. We had fun. Right along with the camp counselors and drug dealers on Virrick Park, we played Spades and Tunk until the cards went soft. My cousins and I jumped from trees in their front yard pretending we were Wolverine, Cyclops, and Beast fighting Magneto and Omega Red. But, there were costs, social and psychological. As I grew older and saw more, I realized how these individual limitations were really societal constraints.

Arguably, Du Bois’ most poignant declaration states, “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.”12 Seeing how social class plays a dominant role in shaping one’s life chances,13 scholars and writers update this assertion and argue that the problem of the Twenty-first Century is the problem of the class line. This may be true, but when you are poor and damn near of any color, you know firsthand that the class line is as white as it is bright. Learning how to navigate both sides of the color and class lines—something that was already rare, but is sadly increasingly harder to do in our neighborhood and local schools— has become as important, if not more, as mastering reading, writing, and arithmetic.14

So I moved her from the school. We moved her. We made my niece apply for a type of dual citizenship, all in the spirit of minimizing her exposure to problems that stem from the callous disregard for the lifeblood of the future of America.

I tried to escape by returning to fiction, from Another Country to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows and everything in between. A kind of literary safe space, if you will. But Baldwin had another lesson for me.

This decision was a collective one. But it was the first time I felt like I really had a say in a family matter. Neither age nor ability to pay bills—folk requirements that purportedly permit one’s voice to be heard in a black household—gave me a true seat at the table. My degrees, however, did. More than proof of academic achievement, they were physical representations of experiences and knowledge beyond what our community could provide. When it came to my niece’s education, I wanted to have my words heard both as an engaged uncle and as a worried sociologist. I made this push not just because I had seen how the other half lived. Sure, I have had more than a few glimpses, but my growing understanding of the structural forces that kept our half stuck in place motivated my more forceful intervention. Coming to terms with our limited options reminded me that what may work for my niece on an individual basis was not an effective social policy for families in similar situations. I struggled with this duality every day. Scholarship programs at private schools constituted an urban brain drain. They institutionalized pathways for poor, talented youth to leave public schools in order to give them a shot at a brighter future. One consequence of this outmigration, however, was that it made the present situation dimmer, darker, and harder for those not fortunate enough to receive that kind of assistance. I was torn.

Neighborhood woes

Commenting on the state of public schools in America, Baldwin asserted, “You cannot talk about schools without talking about cities.”15 The sociologist in me immediately extended that thought to neighborhoods and their lasting effects on youth’s academic and social well-being.16 Some neighborhoods protected you from hurt, harm, and danger. Other communities placed you in the thick of it.17 Worsening social ills in America’s distressed neighborhoods, created by the exodus of jobs that once served as security blankets for one’s finances and promoted community and collective well-being, caused young people to live their lives on the inside looking out.18 I thought of Coconut Grove, my own neighborhood. For me, home was a series of half-remembered dreams of ceramics classes with Ms. Gina and dives into the deep end of Virrick pool. These joyous moments, however, were punctuated with memories of punches in the face on the way home from camp and taunts to fight back as a half-dozen boys surround me, ready to jump in, all for being a nerd, a geek, a bookworm. Still, I played outside. Streetlamps were our curfew. Darkness and danger did not necessarily always go hand in hand. For my niece, however, home was a closeted existence. She ventured outside only to go to and from the car. She knew nothing of her neighbors, not their names or their children’s names. This disconnect was not because she was anti-social. Rather, her limited knowledge of the community was because “bullets carry no names.”

The neighborhood was not what it used to be. The neighbors were not who they used to be. Yet even rampant gentrification could not temper the rise in retaliatory attacks between rivals that left buildings scarred with holes, homes broken from the loss of loved ones, and residents living in fear that they too may be next. Localized terrors were so prevalent that reality television shows like The First 48, which followed homicide detectives, have chronicled more murders of people who I went to school with and walked past on the way to corner store than I care to count. I hated seeing shirts and buttons with pictures of lost souls captioned with “R.I.P.” at community events. The old were not always the closest to the grave.

But the opportunity for my family to move had not come yet. In all honesty, neither had the money. Thinking about down payments and other hidden costs of moving I confronted an ugly truth: “anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”19 Simply trying to make it day to day made it hard to save for tomorrow let alone for bigger purchases down the line, especially when black families, for generations, have been denied the ability to build assets that make such moves realistic.20 But would we have escaped the same troubles I wish my family to no longer experience? What does it mean, in an open and equal society, that black families who earn three times as much as white ones live under similarly distressed neighborhood conditions?21 We were black and, as a family, far from middle-class. Still, that might not have been enough. All too often “the people who have managed to get off [the] block have only got as far as a more respectable ghetto.”22 Segregation, the cancerous sore on society, in many cities across the country, is getting worse.23 I was not sure whether to call it anachronistic or timeless.

Coming to terms with our limited options reminded me that what may work for my niece on an individual basis was not an effective social policy for families in similar situations. I struggled with this duality every day.

More than the money, moving my family would be an uphill battle. My time away has shown me how to build a life outside of the place I once called home. My family, however, has only shared in these experiences through phone calls and photos. But maybe my time away blinded me to facts that my family remains acutely aware of: that even if they were to move, they were likely to endure a new “respectable ghetto [without] the advantages of the disrespectable one—friends, neighbors, a familial church, and friendly tradesman; and it is not, moreover, in the nature of any ghetto to remain respectable long.”24 It is impressive how family often delivered lessons that books simply could not. Tired of waging battles for relocation with my family where I was outgunned, I sought out private schools to at least give my niece greater access to resources and experiences to better prepare her for life beyond high school.

The mis-education of America

I cannot run from this decision. The consequences of differential exposure to impoverished conditions and uneven access to resources were what I studied day in and day out. The need for relocation forced me to ask, what kind of society—ostensibly one built on twin pillars of equality and justice—reneges on the promise of providing every person housed within its borders the right to an education?25 And, if it is not too much to ask, at least an education worth having, that is not outdated, outmoded, or just plain wrong. How is it that our schools are so underfunded that teachers resort to using extra credit as incentives for students to bring in school supplies? Responding to budget cuts that only exacerbate problems caused by unequal funding, I have seen teachers offer 5 points for bringing in chalk. Ten points for dry-erase markers. An extra credit “A” for a ream of paper. Already financially strapped parents took on extra economic burdens to support a school system that should be training the next generation of citizens. Instead of investing in rebuilding the infrastructure of American schooling, we were quickly becoming a nation overrun by an alphabet soup of teacher corps that pose as stitches to deep wounds of educational inequities when they really are Band-Aids. Too many children have been left behind. As long as we permit savage inequalities to maintain their grips on public education the nation will never reach its full potential.26

It was not just issues with funding. I wanted my niece to have more diverse experiences than I had. But could she have had them had she stayed put? In 2015, 51 percent of public school students across the country live in poverty.27 For the first time, that is a national majority. But these new numbers reflect an old reality for generations of black and brown communities.28 Why all the headlines about a “new majority” now? In Florida, the number was higher. In schools like those that children in my neighborhood went to, the numbers, and stakes, were higher still. With that said, however, poverty rates only told half the story. Too little cross-racial or cross-class contact existed in these schools. Where are the opportunities to interact with and learn from each other? Where are the moments for breaking down stereotypes when students do not have personal experiences that serve as the rule and disprove the prejudicial exceptions?

Maybe my time away blinded me to facts that my family remains acutely aware of: that even if they were to move, they were likely to endure a new “respectable ghetto [without] the advantages of the disrespectable one—friends, neighbors, a familial church, and friendly tradesman; and it is not, moreover, in the nature of any ghetto to remain respectable long.”

In too many schools, in far too many communities, the only white people that students saw were either teachers in classrooms or police officers in hallways. And biases, amplified by troubled surroundings, ran wild. These schools suspended black students more than whites. Young, black girls faced this fate more often than any group.29 Being young, black, and gifted does not translate into innocence. Uneven policing ran so rampant that, in Miami, the school board had to invest millions to find alternative disciplinary practices. That was a double slap in the face: using taxpayer dollars to fix policies that were discriminatory and prejudicial at origin.30 That was wrong. That was Miami.

I did not want my niece’s energies taxed by fighting battles that no child should be forced to face. I wanted her to use her energies on being engaged academically. I wanted her to be challenged artistically and pushed socially. I sought an out for her, an alternative that would not be hampered by staying local or limited resources. Sadly, that meant private school. In a nation whose highest court declared that education “is the very foundation of good citizenship” more than six decades ago, the reality is that the schooling afforded to all is not equal to the education that the rich can afford.31 Chief Justice Warren’s words and ideals live on. But so do his fears that we may fall short.

A deep-seated opportunity gap remains. And it has grown. I saw these bastions of privilege as the place where her greatest chances lie in being allowed to find and show her talents. Teachers at these schools were supported and given time to recognize, let alone cultivate, those talents.32 Even academically successful, zero-tolerance public schools cannot offer similar levels of independence as their policies demand discipline and foster deference.33 Always with an eye toward moving my niece into her freshman dorm, because I have long grown tired of only celebrating high school graduations, I want her to be part of the growing minority of poor students of color making it into college.34 Private school looked like the right path, or at least, the only option.

New place

Beyond the upkeep of her private school with its manicured lawns and Olympic-sized swimming pool, beyond its computer lab and ceramics studio, beyond its multi-purpose rooms and open-air spaces, the language used at my niece’s end-of-the-year celebrations was as refreshing as it was shocking. She and her peers learned more about the French Revolution for one play than I ever did in all my years of schooling. She used Wordly Wise words that I learned in middle and high school. I was floored. But

I was the only one shocked. My niece and her peers found these “big words” quite quotidian. The gulf between what my niece experienced every day in school compared to her peers from similar backgrounds was humbling. When teachers must fight for funding for basic needs while breaking up fights between students, they will never be able to fully engage their pupils on the moral lessons in The Bluest Eye or The Odyssey. That is, if students were ever allowed to work with primary sources and not just textbooks. When students must fear for their safety as neighborhood woes become school problems, which then become nightly news, they will never be able to devote their attention to differences between theorems and postulates or how light acts as both a particle and a wave.35 When entering school felt more like walking through “the trap” at a prison where all eyes are on you like a modern-day panopticon than entering a place of learning, how can you focus on what is in front of you if you are constantly watching your back? Even for those who aspire to go to college, they face additional hurdles like being one of 500 (or more) students for each guidance counselor, more than double the recommended national average.36

Being young, black, and gifted does not translate into innocence. Uneven policing ran so rampant that, in Miami, the school board had to invest millions to find alternative disciplinary practices. That was a double slap in the face: using taxpayer dollars to fix policies that were discriminatory and prejudicial at origin. That was wrong. That was Miami.

Students, because of where they live, a choice that was not theirs, and probably not even their parents’, must possess the grit and resilience to endure structural constraints and physical dangers.37 The path to college was even more daunting when you saw what others were exempt from enduring along their trek towards adulthood.

Old path

What I did was nothing new. Families across the country have adopted this strategy to give their children a fighting chance for decades. I came to this decision after home life combined with research to put American educational disparities in sharper relief. Organizations like A Better Chance and Prep for Prep institutionalized this practice.38 These programs facilitated a sponsorship system where wealthy patrons place poor students in private schools, an urban (and rural) brain drain that begins long before college. Academically talented, lower-income youth were receiving scholarships to boarding, day, and preparatory schools that were more resourced, more encouraging of independent thought, and more focused on college placement than their zoned high schools. They were also whiter. I do not mean to equate white with right or something inherently better. History is littered with counterexamples. However, in a country where being black made one 3/5 of a man and being Latino reduced one to visa status, whiteness meant far more than who sat with you in a classroom. It means access to support and funding as well as sympathy when things do not always go according to plan.39

When lower-income undergraduates who traveled this sponsored path spoke about their trajectory to college, they recounted experiences you would not expect them to have. Their schools have high-tech research lab space where they carry out complex experiments instead of devoting limited resources on security to keep neighborhood problems at bay. Their teachers have terminal degrees who promoted independent learning, free from teaching to standardized tests that neither measure intellectual growth nor gauge students’ potential. Lessons routinely included private screenings of documentaries with directors instead of watered-down versions of history from textbooks. Social calendars were littered with dinners with heads of state and private tours of national treasures instead of depleted funds that removed even field trips to local museums. They even traveled or studied abroad as part of their classes. Privileged experiences became commonplace for those from humble means.

These experiences matter, especially as colleges looked to private schools for both their new diversity and their old money. Maybe that was why, on average, half of lower-income black students at elite colleges are alumni of private schools despite black students from all class backgrounds representing less than 10 percent of all the students at private schools.40

New faces, new problems

I was excited about the opportunities that this uprooting would bring. But, from firsthand experience and from watching tears fall from students’ eyes when recounting their high school days, I was also cognizant of the new battles that would have to be waged. There was a price to this ticket.41 I knew this first hand. I did it. I left Coconut Grove every morning and headed to Gulliver Preparatory. The “diversifiers,” those of us few students from nontraditional backgrounds, who attend these schools, as one scholar called them, were taxed.42 Moving from poverty to privilege on a daily basis was a daunting task. Increased exposure to whites, especially whites who have been sheltered from interacting with those who do not look or live like they do, meant increased exposure to ignorance. I will never forget after my last high school football game, another student—an arrogant, blonde swimmer—asked if I would return to public school now that the football season was done. To him, despite he and I sharing the same International Baccalaureate and Advanced Placement classes, I was hired help. Diversifiers must be mentally strong in a way distinctively different from their peers in public schools. They must, we must, straddle two worlds, slowly losing citizenship at home as we apply for visas in a new place. I asked my niece to do so earlier than I had done.

This last aspect of my niece’s experiences has led to interesting conversations between me and my family, especially between me and my mom. My niece’s school is Catholic. I am technically Baptist. My brother is more so than I am. My mother is African Methodist. My nieces are culturally Christian despite spending Sundays at home because they do not have the “right clothes to wear.” (So many rules for a place that allows you to “come as you are.”) Yet there were concerns that my niece might get mixed signals about religious belief. Seeing this objection not as a matter of faith, but one of familiarity, I pushed back. I asked how could messages be mixed if there is only one.

A more glaring cultural clash, however, occurred over summer programs. I was adamant that she needed to do something to prevent summer learning loss. No longer would she spend another summer cooped up in the house. My niece voiced that she was weary of going to the local park and would rather attend a shorter program at the Museum of Science. This preference did not sit well with my mother. She said that my niece, “Needed to connect. … ” Before she could finish, I asked, “Connect to what?” There was some resistance to being too disconnected from home. Not always at the forefront, this worry rested just below the surface. I would love for my niece to straddle both worlds and, more importantly, want to do so. And I think she did. After attending both camps, she made friends—from both sides of the tracks.

Diversifiers must be mentally strong in a way distinctively different from their peers in public schools. They must, we must, straddle two worlds, slowly losing citizenship at home as we apply for visas in a new place. I asked my niece to do so earlier than I had done.

In many ways, my niece was more comfortable with this symbiotic duality than I was. But I think it interesting that these conversations of authenticity came up only after immersion into private school and the incorporation of some of her classmates’ mannerisms and likes even as they sat alongside those she picked up at home. Unlike many friends I have lost along the way, I do not believe my mother thought of me as a sellout for my pursuit to live a life less laden with reminders that citizenship is limited to one’s inability to pay. Nor do I believe that she perceived that my niece would be a sellout either. Of that I am sure. Sometimes there was a fear that I “buy in” with a little too much vigor. At times, I thought she was right. But like G. in “Nobody Knows My Name,” I know not to reveal too much. The role of son and sociologist sometimes clash.

New obstacles surface for new admits that go beyond connecting to peers and acculturating to new norms. Sometimes scholarship students must battle teachers who may treat them with less patience and less leeway than their paying peers. My niece came home upset one day, brought to tears for the first time that I could recall from a racial incident. Her teacher called her a “spoiled brat” in front of the class. Hearing the details, rage welled up inside me. I was angry in a way that I had not been since the teacher at Gulliver asked me, in front of everyone, “Did I really write this paper?” because it was of such high quality.

But the pain was different. It hurt more. It cut deeper. The teacher was not attacking my academic integrity. That, I can handle. She was assassinating my baby niece’s character. How one of the poorest students at the school could be a spoiled brat is beyond me. But if I were to be more analytical than reactionary, something that becomes increasingly difficult when family and research collide, I would say that the teacher misrecognized what she saw. See, when my niece stood her ground on a project topic that she wanted to do, the teacher did not read it as a young woman demonstrating her investment in a project and standing up for herself, one of the principles they teach the young women who come through their doors. No, she saw a little black girl defying her authority even as her peers made similar cases for their choices of assignment.

Trying to keep a cool head, I spoke with my niece on the way to school the next day. I told her, in no uncertain terms, that she can never let someone call her out of name, not family, not friends, not foes. We discussed assumptions people will make about her because of her race, her gender, and her address. So many battles for someone so young. We discussed lessons I wish I had heard about navigating privileged, white, places and those who occupy them. Despite what the old song says, mama could not tell me there would be days like this. But, for my niece, she had me. She entered the meeting and told the head nun exactly what happened. Instead of angry outbursts, which would have been justified, she laid out the facts. She explained how the teacher made her feel and asked why the teacher did not pull her aside if there was a problem as she did with the other girls. She did not back down. My niece had not only expanded her taste for music and movies by hanging out with different people. She had expanded her cultural repertoire and developed a sense of entitlement to her teachers’ time, and more importantly, to equal treatment from them.

But hurdles persist. Is this the price we must all pay for equal opportunity, any shot at a better tomorrow? It is a heavy burden to have to carry for someone so young.

New way forward

Where do we go from here? For a long time, I admit, it was neither the past nor the present that scared me the most. I was not always sure that tomorrow would, indeed, be a brighter day for “the future is like heaven—everyone exalts it but no one wants to go there now.”43 But my grandmother used to tell us, “Keep seeing a few more risings and settings of the sun.” In other words, keep living. Remembering how far we have come as a nation, as a family, I am at once cautiously optimistic and torn. What I hear on the phone calls home amplifies what I read in books, but somehow hope snuck in when I think about how we, as a family, were not now where we once were and how I, with opportunities and resources never afforded to previous generations, can dedicate my life’s work to making it easier for young people to follow their dreams.

As an uncle, I can geek out with my niece about science and art as well as help her navigate social worlds that were once new to us all with a bit of insider’s knowledge. She has access to specific advice and general support whereas I only had the latter at her age. I took solace in that. Yet, I know, this may still not be enough.

So many battles for someone so young. We discussed lessons I wish I had heard about navigating privileged, white, places and those who occupy them. Despite what the old song says, mama could not tell me there would be days like this. But, for my niece, she had me.

But as a sociologist, I must think about addressing individual effects and their causal roots. I saw hope in working toward “durable” investments, the type of structural changes that uproot deep-seated inequalities that plague too many communities filled with people who look like my family.44 It is possible to fundamentally change how neighborhoods and schools affect the life chances of those born within their borders and educated within their walls. We need true investments that combat inequality-sustaining laws like Milliken v Bradley that reinforced barriers and amplified black/white divides.45 For example, there are lessons to be learned from education experiments that link high schools and colleges, integrating the latter physically and structurally into the former.46 These schools created scaffolding advising, where students are immersed in intergenerational communities where development is the primary concern and college is just one goal. More than just examining what one or two schools do right, their success reminded us that we must create supportive learning environments where both teacher and pupil have opportunities to showcase their skills.

We must find ways to foster growth and combat inequalities that have a stranglehold on our fragile democracy. I have to believe we can; it is this thought that keeps me going. It is physically tiring, emotionally draining, and just plain unfair. But we must find the courage, conviction, and compassion to not only enact such important policies, but also to fuel our hearts and minds as we fight to cash in on America’s original IOU. It is rather a simple ask: be true to what it put on paper. For somewhere I read “that all men are created equal.” We all, especially the next generation, should be, must be, treated as such.