Books about Congress are too often either dry and scholarly or lively and superficial. It is rare to find one that draws in the reader but does not sensationalize the topic or get bogged down in minutia.

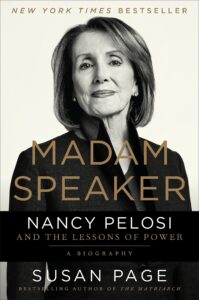

In her new biography of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Susan Page takes us behind the scenes during key events of recent political history while chronicling the life and career of a transformational woman in an engaging manner. While Page conducted several interviews with her subject and clearly admires her, Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Political Power is no work of is hagiography.

Pelosi is the first female to hold the top spot in the House of Representatives and one of the most powerful. During her two stints as speaker, from 2007-2011 and 2019 to today, she has helped engineer many of the legislative victories of Presidents Barack Obama and Joseph Biden and was an aggressive opposition leader during the presidencies of George W. Bush and Donald Trump. One key to her success has been that she tempers her often aggressive tactics and use of sharp elbows with a graciousness and charm that often comes from being in the upper social strata. It is a variant of a phrase Peggy Noonan, a speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan, used to describe former first lady Barbara Bush (the subject of an earlier Page book), “Greenwich granite.’’

Page, the Washington bureau chief of USA Today, contends that Pelosi both benefits and is harmed by being “regularly demonized and routinely underestimated.’’ (312)

While the shorthand description of Pelosi is often that she is a “San Francisco liberal,’’ that is an incomplete assessment. Her father was a congressman and three-term mayor of Baltimore and she learned the nuts and bolts of politics as a young girl, including the “favor file’’ that her mother regularly kept as part of the family political organization. As a result, Pelosi had a ringside view of how to set up and maintain a campaign apparatus and the ins and outs of getting things done once you win.

Susan Page, the Washington bureau chief of USA Today, contends that Pelosi both benefits and is harmed by being “regularly demonized and routinely underestimated.’’

Page chronicles the mayoralty and ethical transgressions of Thomas D’Alesandro in great (sometimes excessive) detail. While some of it was interesting, this is an instance where less might have been more.

Pelosi moved to San Francisco because that is where her wealthy businessman husband Paul is from. Her considerable political skills and husband’s bank account fueled her rise through the ranks of the Democratic Party. She was underestimated and often dismissed as a wealthy dilettante. Pelosi had the last laugh, however. She won the first race she ran, a special election for the U.S. House in 1987.

Once in Congress, she succeeded in getting legislation passed on human rights in China and increased funding for AIDS research and treatment. That work and her prodigious fundraising helped fuel her rise in the leadership and she eventually won the top job in her party.

The late Supreme Court Justice William Brennan was fond of saying that one of the most important skills for a member of the court to have is the ability to count to five, in order to achieve a majority. For Pelosi, the magic number is usually 218, and on the big votes she rarely comes up short.

She is not prone to invade people’s space, a technique preferred by Senate Majority Leader and President Lyndon Johnson. Her style is calm, but firm, a skill set she often used effectively when raising the five Pelosi children.

“I consider myself a weaver. I’m at the loom valuing every single thread for what it brings, he or she, brings to the tapestry and the beautiful diversity of it and the strength of it,’’ Pelosi told Page. (355)

The late Supreme Court Justice William Brennan was fond of saying that one of the most important skills for a member of the court to have is the ability to count to five, in order to achieve a majority. For Pelosi, the magic number is usually 218, and on the big votes she rarely comes up short.

Christine Pelosi, one of the speaker’s daughters and an accomplished political operative in her own right, described her mother as follows: “She is always whipping or weaving. And even when she’s not whipping a vote, she’s always counting.’’(355)

Those skills paid off when Pelosi led the efforts to pass the Affordable Care Act, the most significant domestic policy achievement in recent years. Most people know it better as Obamacare.¹

With unanimous Republican opposition, and nervousness among some moderate and conservative Democrats, Pelosi had little margin for error. But she helped cut deals, held the figurative hands of those who needed it, and pushed Obama not to scale back the plan too much. Another problem was that Obama did not enjoy the nitty gritty politicking that is needed to accomplish things on Capitol Hill. He thought much of that was beneath him and was more of a big-picture person. No one will ever confuse him with LBJ.

Page’s chapter on that bill is fast-paced and puts the reader in the room, without getting bogged down with excessive jargon or wonkery.

“Some on Pelosi’s team suspected the White House never felt confident the bill could be passed –not an unreasonable concern, all in all—and that they were happy to make it more the Speaker’s fight than their own, just in case it failed,’’ Page writes. “She had to work to get some votes she thought the White House could have delivered.’’(240)

While Obama presented an array of challenges for Pelosi, at least she believed they were mostly working toward common goals. The same could not be said for President Donald Trump. Not only did Pelosi loathe his policy agenda, but she thought personally he was beneath contempt.²

She was also an astute leader of the opposition.

During much of the first year of her second stint as speaker, she resisted the efforts of several of her caucus’ most liberal members to begin impeachment proceedings against Trump. Part of her reasoning was practical. She initially doubted there were enough votes among House Democrats, assuming few, if any Republicans, would support it. Pelosi was also skeptical that there would be 67 votes to convict in the Republican-controlled Senate.

Ever the vote counter and protector of her flock, she was reluctant to force her members to take a tough vote if it was just to score political points. She also doubted there was sufficient evidence linking Trump to Russia during the 2016 campaign to warrant impeachment. In addition, even though Trump’s overall approval rating was always below 50 percent, several members of her caucus represented districts that supported him.

While Obama presented an array of challenges for Pelosi, at least she believed they were mostly working toward common goals. The same could not be said for President Donald Trump. Not only did Pelosi loathe his policy agenda, but she thought personally he was beneath contempt.

Pelosi and her fellow leaders changed their minds when evidence surfaced that Trump had threatened to withhold financial assistance from Ukraine if the country did not launch an investigation of the business activities of the family of former Vice President and likely presidential candidate Biden.³

Trump was of course impeached, but found not guilty in the Senate, mostly along party lines. Page chronicles Pelosi’s active involvement in devising the impeachment strategy and even stayed up in the middle of the night while leading a congressional delegation abroad during the Senate trial. Page does not second guess the wisdom of Pelosi’s approach.

Unfortunately, the book was completed before much of the action in the 2021 impeachment took place, following the January 6 insurrection in the Capitol. It would have been fascinating to have learned about Pelosi’s role in devising and implementing her party’s strategy, especially since the evidence against Trump was much stronger the second time around.

The U.S. House has had just a handful of speakers who can truly be described as transformational. In modern times only Newt Gingrich and Pelosi fit that description.

Gingrich, who served from 1995 to 1999, not only brought the Republicans back to the majority after a 40-year drought but also centralized power in his office and enabled the chamber to operate efficiently and pass major legislation such as welfare reform.

Although Pelosi is the ideological opposite of the gentleman from Georgia, she has led her caucus just as forcefully and used some of the same strong-armed tactics. She has also made life difficult for some Democrats who disagreed with her on key issues or crossed her politically. But her political skills were instrumental in getting the House to pass several key measures.

In addition to the aforementioned Affordable Care Act, her key accomplishments include the financial rescue package of 2008, the Dodd-Frank Act which overhauled financial regulation and established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the stimulus package put forth by Biden earlier this year.

Oddly, Page does not spend any time on Dodd-Frank and unfortunately the action on the stimulus bill took place after the book was finished. Also, while Pelosi gave Page several interviews, she rarely talked about personal subjects. As a result, the reader does not come away with much of a sense of what Pelosi the person is like.

Despite those shortcomings, Page’s book is an enjoyable and insightful look at one of the country’s most significant political leaders.