Marty Schottenheimer and the Meaning of Coaches

A renowned football writer remembers how great a coach can be, even if he does not win the big one.

March 30, 2021

My actions are my only true belongings. I cannot escape the consequences of my actions. My actions are the ground upon which I stand.

—Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh

In this is the true artistry in my profession: the ability to do the right thing at the right time at the right place for the greatest possible number of times under the stress of a game.

—Football coach Paul Brown

There comes a point in one’s life as a sports fan, when aging and reality and a smattering of wisdom start catching up with you. You may still have posters of athletes on your wall, you may still go to games wearing your favorite player’s jersey—but as the years progress, some ineffable shift in focus starts, and you begin to realize the importance of, and start identifying with the predicament of, the head coach. Gradually, the admonitions and exhortations that you find yourself yelling during games sound more like things yelled by coaches than by teammates. As Chuck Noll once said about his first years in coaching, “I became aware of how much I wasn’t aware of as a player.”

This change occurred for me in my late 20s and early 30s, and coincided with becoming a parent. Suddenly, amusement parks became less enjoyable as I began to understand all the things that could go wrong there. Similarly, as I aged out of the athletes’ peer group and toward the coaches’ peer group, I became more aware of the complex interrelationship between players and coaches, and the fragile ecosystem of teams.

It was around then, in the early ’90s—when I was ostensibly becoming a full-time adult—that I became devoted to Marty Schottenheimer. He was part of my growing up.

• • •

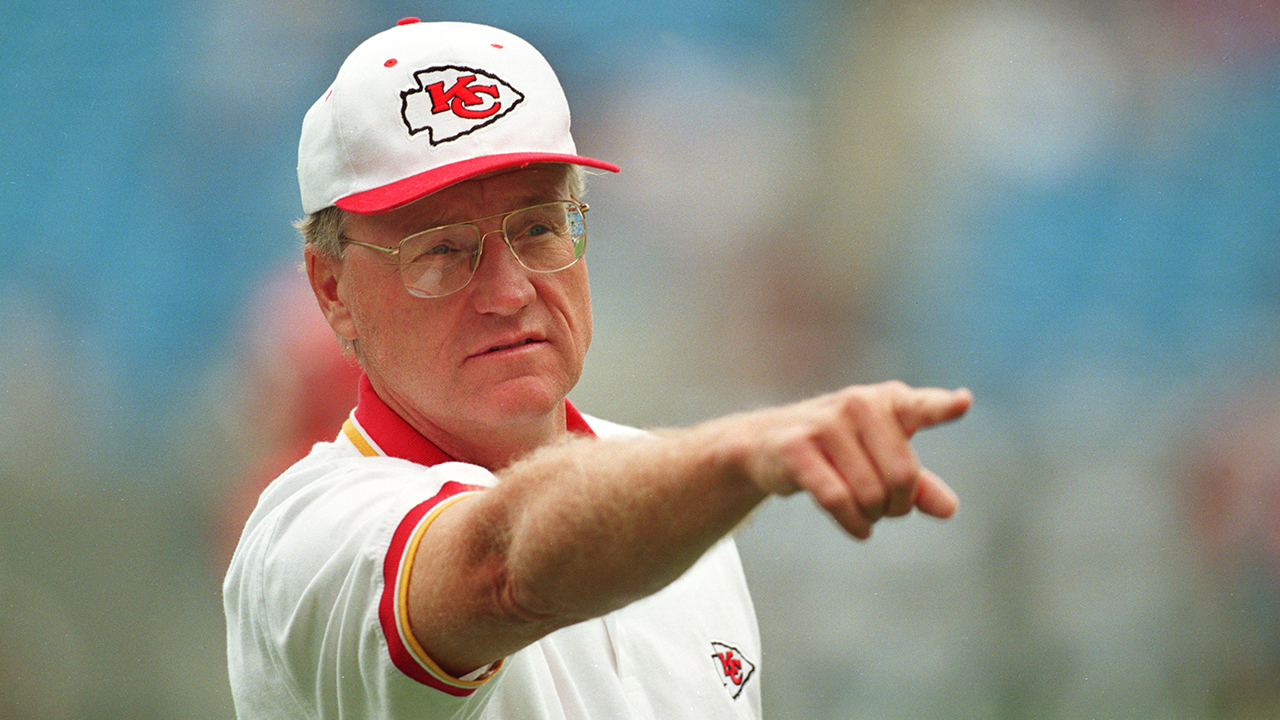

In almost any period in the past 50 years, Schottenheimer could have been cast as the “square” dad in a situation comedy. He was the quintessence of matter-of-factness, the earnest striver whose word was always good, but who would not have known the latest dance moves—or even the name of the latest dance. Schottenheimer exhibited a strain of cheerful seriousness or serious good cheer, take your choice.

He had a commanding presence, based in large part on his love of the curriculum of football, and his ability to convey the component parts to his players. Football coaches succeed when they can get players to sacrifice for the common good, and then realize positive results while doing so. This happened countless times for Schottenheimer’s teams. He found success throughout his coaching career—building Cleveland into a perennial power in the mid-’80s and reviving the Chargers’ fortunes in San Diego in the early 2000s. But his impact was felt most clearly at the place he stayed the longest, in Kansas City during his 10-year tenure as head coach of the Chiefs.

His death last month prompted a minor furor in the world of sports. The obituary headline in the Washington Post was as remorseless as the sound of a judge’s gavel: “Marty Schottenheimer, NFL Coach Whose Teams Wilted in the Postseason, dies at 77.” It seemed that one of the winningest coaches in football history was destined to be defined by his playoff failures. Fans in Cleveland, Kansas City and San Diego knew all about these agonizing setbacks. (Buy me a drink; I can tell you war stories.) But while those losses were part of the story, they were not all the story, or even its main part. For that you had to understand what Schottenheimer accomplished, what he changed in the team and the city and beyond.

I grew up in Kansas City, a full-fledged true believer. In 1970, I had watched Super Bowl IV as a six-year-old dressed in a Chiefs uniform, cheering the team on to a world title. Two years later, on Christmas Day in 1971, I was an eight-year-old traumatized and reduced to tears by the Chiefs’ inexplicable double-overtime playoff loss to the Miami Dolphins in the longest game ever played. The first cut is the deepest.

His death last month prompted a minor furor in the world of sports. The obituary headline in the Washington Post was as remorseless as the sound of a judge’s gavel: “Marty Schottenheimer, NFL Coach Whose Teams Wilted in the Postseason, dies at 77.”

From there, the team went into a kind of free-fall for the rest of the ’70s and much of the ’80s. To a national football audience, they became anonymous, invisible, irrelevant. When Kansas City finished its 1988 season with a 4-11-1 record (their 11th losing season in 15 years), the team had experienced an unconscionably long run of ineptitude in a league built on parity. The Chiefs had become the object of such widespread ridicule that Chris Berman, the host of ESPN’s NFL PrimeTime show, had taken to referring to them—repeatedly and over a number of years—as the “Chefs.”

Then they hired Marty Schottenheimer. And things instantly changed.

The Chiefs were not rebuilt so much as transformed. It was under Schottenheimer (and visionary executive Carl Peterson) that the team became instantly competitive, and Arrowhead Stadium went from being a handsome but sterile modern football facility to being something much more: a fiesta, a fandango, a fortress—one of the best places in the world to watch a football game, and one of the most difficult environments in the league for visiting teams.

I left Kansas City for college in 1981, and have not lived there since. But starting with the home opener in 1989, I began arranging trips back home each year–sometimes two or mor –to watch the team of my youth. Marty Schottenheimer’s teams brought me home.

There is something quietly powerful, after years of dismal results, about having your hometown team suddenly strong again. I was living in Austin by the time it happened, and reveled in the resurgence. And like countless others, the mere fact that the Chiefs were respectable meant that watching each week’s game—even while living 750 miles from Arrowhead Stadium with almost none of their games televised in the local market—became compulsory. Schottenheimer’s first season in Kansas City, 1989, was also the year I started casting about the highly disorganized sports bar scene in Austin. It was the era before the NFL Sunday Ticket package, when finding an out-of-market game was a matter of luck, politesse, and hoping the bartender on duty was proficient at navigating a satellite dish in such a way to pick up a game on Telstar 301. It was in those sports bars in the early ’90s that I met an assortment of fellow dislocated Kansas Citians, a few of whom would become friends for life.

By Schottenheimer’s third season, 1991, no one was calling us the Chefs anymore. Those on the field and at the stadium on the night of Oct. 7, 1991 still speak of the scene for that Monday Night Football game—the Chiefs’ first prime-time national TV appearance in six seasons—as an unforgettable night. It was the coming-out party for a new generation of Chiefs fans, as Derrick Thomas and a relentless pass rush harried the undefeated defending AFC champion Buffalo Bills, in an emphatic 33-6 win. The stadium that night was a throbbing din, as many of the 76,120 in attendance remained standing throughout the game. “I’ve never seen anything like that in my life, before or since,” said Tony Dungy, then an assistant coach for the Chiefs.

It was the night when all that Schottenheimer had built coalesced. “I could tell when we came out for warm-ups that the crowd was going to be a factor,” he said after the game. “The crowd was so alive that it made the hair stand up on your arms.”

The Chiefs had become the object of such widespread ridicule that Chris Berman, the host of ESPN’s NFL PrimeTime show, had taken to referring to them—repeatedly and over a number of years—as the “Chefs.” Then they hired Marty Schottenheimer. And things instantly changed.

For me, the scenes at Arrowhead were like a beacon; I wanted to be there, to be part of it. My mother had moved back to her native Chicago, so by the mid-’90s, when I thought of “going home” to Kansas City, the place that felt most like home—both in the sense of the place I knew best, but also the place I returned to most often when I came back—was Arrowhead Stadium.

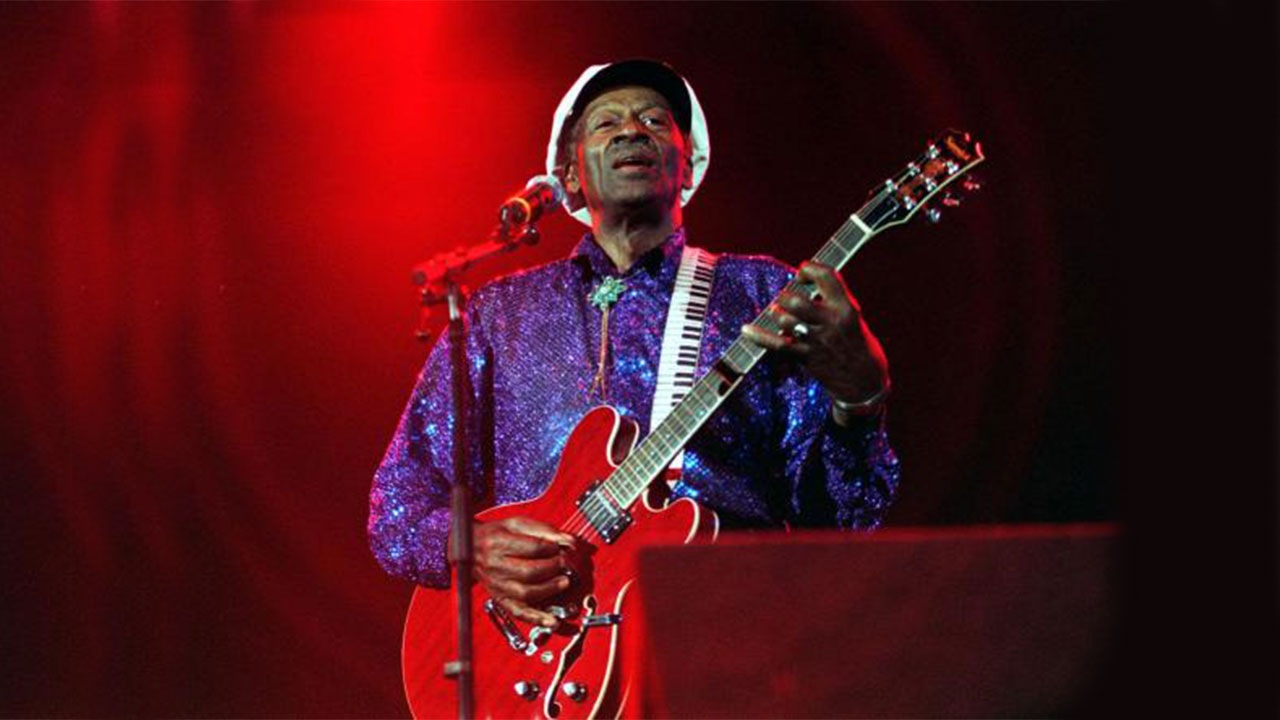

It was ridiculously loud. It was gloriously welcoming, with row upon row of tailgates and portable grills in the parking lot pregame. Walking down any row of cars, you might hear a musical mélange that included Eagles, Marvin Gaye, George Strait, Stevie Wonder, Willie Nelson and 2Pac from the sound systems.

It had become an extraordinary slice of Americana. And it was, in a real sense, Marty’s house.

• • •

Nearly every great coach is a great teacher first. And the best coaches never stop being great teachers, even after they are elevated to the top of their profession.

Schottenheimer’s philosophy—“Martyball,” as it was called—respected football’s eternal verities: it was a sound, tough, intelligent approach to the game, stressing strict adherence to fundamentals and discipline, with a healthy dose of emotion. Don’t beat yourself, do the simple things well and consistently, play passionately, and you will prevail often. (One of the most revealing indices of coaches who preach discipline is turnover differential, and every one of Schottenheimer’s Kansas City teams finished in the plus category; they always took the ball away more than they gave it away.)

And the teaching never stopped. NFL Films would often catch Schottenheimer on the sidelines during a break in the action, staring straight into the eyes of one of his players, a hand on each shoulder, to command undivided attention. He was still teaching during the games.

His pregame speeches were monuments to unified purpose—index finger extended to emphasize the point, eyes intently searching those of his players, Schottenheimer would intone, “There’s a gleam, men…” His Chiefs would take that gleam into action, posting winning records in each of his first nine seasons in Kansas City.

The lesson was clear: The eternal verities worked. A solid offensive line, a strong running game, a defense that got pressure on the quarterback with only four men rushing, a linebacking corps that could fill gaps and tackle in the open field, and a secondary that was full of ballhawks with short memories. Defense was Schottenheimer’s metier, his natural element.

But offensively, the Chiefs could be one of the least exciting teams in football. Have you ever watched someone packing for a trip in the most deliberate way imaginable? The sporting equivalent was the Chiefs’ offense in the early ’90s. Thudding off-tackle runs. Humble flare patterns to gritty possession receivers. A journeyman quarterback, Steve DeBerg, whose single greatest skill was the play-action fake.

NFL Films would often catch Schottenheimer on the sidelines during a break in the action, staring straight into the eyes of one of his players, a hand on each shoulder, to command undivided attention. He was still teaching during the games.

We did not care. We were finally winning. And nowhere were Schottenheimer’s transformative powers more apparent than against the Chiefs’ longtime archrivals, the Los Angeles/Oakland Raiders. By the end of the 1988 season, the Silver and Black had won 21 of the previous 30 games between the two teams, dominating the series that was once the most bitter and hotly-contested rivalry in all of football.

As soon as Schottenheimer arrived, “Raiders Week” began to take on a different aspect. Over the next ten years, Schottenheimer’s Chiefs sported an 18-3 record against the Raiders. Many coaches have made a priority out of rivalry games, but Schottenheimer went beyond that. He viewed character as destiny. He made a case to his players that despite the Raiders’ talent, their undisciplined style would cause them to make mistakes eventually. And the Chiefs would win the game if they held on, stayed close, played smart. Then he constructed a team that would capitalize on those inevitable Raider errors.

“One play at a time. Stay together, play together, we’ll get it done.”

They would do that, and a lot more. Under Schottenheimer, a new generation of fans would become devoted to the Chiefs and the modern incarnation of Arrowhead as the loudest stadium in the world began to take shape.

We loved the mantle of virtue that Schottenheimer provided for us. And yet, among my friends–the zealots who followed the game as if it were a religion—deep down we thought we knew better. For all our gratitude for the stout defense and sound, self-contained offensive strategy, we sensed that Marty was too conservative, too narrow-minded, too square to be truly capable of the brilliance the best football coaches needed to get to the top level. He was using Lombardi methods in the age of Bill Walsh.

Yet Schottenheimer was a master at taking what was given him and finding a way to succeed. On Dec. 28, 1991, the Chiefs played their first playoff game in the 20-year history of Arrowhead Stadium. My friend Rob and I drove up from Texas for the game, meeting another friend from Austin, Brad, at the stadium. It was a cold Saturday morning, and the two teams staged the sort of desperate, pitched battle that is so characteristic of playoff football.

For all our gratitude for the stout defense and sound, self-contained offensive strategy, we sensed that Marty was too conservative, too narrow-minded, too square to be truly capable of the brilliance the best football coaches needed to get to the top level. He was using Lombardi methods in the age of Bill Walsh.

In the fourth quarter, clinging to a 7-6 lead, the Chiefs drove down to the Raiders’ one-yard line. But on fourth-and-goal, Schottenheimer played it safe and chose to kick the field goal.

And in the chilled bedlam of the stadium that day, we all complained.

Rob and I exchanged a look. This was Marty being Marty. Too safe. Too fundamental. Too conservative. Nick Lowery converted the chip-shot 18-yard field goal, and the Chiefs led by 10-6.

The two teams continued to careen back and forth, engaging in a sort of trench warfare that would be almost unrecognizable in today’s pro football. And we nervously waited for Schottenheimer’s conservative decision to do us in.

But he knew his team, and had faith in his defense to repel the Raiders and their overmatched rookie quarterback, Todd Marinovich. In those waning minutes, as the Raiders tried to drive the length of the field for the touchdown they now needed because of the four-point lead chiseled out by Lowery’s field goal, Schottenheimer’s methods were borne out. Another interception, the Raiders’ sixth turnover of the day, and the Chiefs ran out the clock. We left Arrowhead jubilant, and a bit sheepish.

“Okay, I’ll admit it,” I said to Rob, while walking out of the stadium. “Marty was right.”

• • •

But as the ’90s progressed, we were right, too. More often than not, safe, solid ball-control football got you only so far. The Chiefs needed more of what coaches like to call “difference-makers,” the elite players who can conjure up moments of athletic and competitive genius. After an early playoff exit in 1992, Kansas City traded for legendary quarterback Joe Montana and signed free agent running back Marcus Allen. They got close that next season, but after winning two playoff games to advance to the 1993 AFC Championship Game at Buffalo, the Chiefs lost to the Bills and never won another playoff game under Schottenheimer.

Losing playoff games—especially at home—can take a terrible toll, on teams and fans alike. There was an inexplicable 10-7 home playoff loss to an inferior Colts team in 1995. And then, in 1997, the Chiefs lost a 14-10 heartbreaker to the Denver Broncos and John Elway. During his coaching career, with both the Browns and later the Chiefs, Schottenheimer became Ahab to Elway’s great white whale. Except, in this instance, the whale kept eluding him and capsizing the boat come January.

In 1998, in an effort to bring in more “difference makers,” Schottenheimer misread the volatile alchemy of the team. There wasn’t a gleam. It was his first losing season, after which he stepped away from the job. Watching the farewell press conference, I felt both grateful and sad. For a decade, he had given it his all; if there was a regret, it was that he had gone down in that last season with a team plagued by too many selfish, flaky, and undisciplined players. It was the Marty Schottenheimer team that was least like a Marty Schottenheimer team.

• • •

So how should he be remembered? In Cleveland, the playoff losses that scarred a generation of fans–“The Drive” and “The Fumble”–are now today rightly viewed as part of the glory days, the best period in the past fifty years for Browns fans. In San Diego, where the Chargers no longer reside, the franchise never had a better record than the 14-2 mark they posted under Schottenheimer.

In Kansas City, it is different. Recent years have seen the rise of Patrick Mahomes, a Super Bowl win, and the exorcism of decades of frustration and heartbreak. It is probably true that there has never been a better time to be a Kansas City football fan.

But to the degree that Arrowhead Stadium is a modern American icon of sports, and the gameday tailgating scene is the standard against which all other professional stadiums are judged, those things started in the ’90s. Schottenheimer’s teams set the blueprint for all that has followed in Kansas City.

It is understandable that so much is written and discussed about the heartbreaking playoff losses in the ’90s at Arrowhead. But it is worth remembering that they hurt so much precisely because, under Schottenheimer, Chiefs fans rediscovered hope and belief, for the first time in decades.

Sports are about results, of course. I remember talking to the coach-turned-broadcaster John Madden early in the 2000s, more than twenty years after he had retired from the coaching profession. I asked him if it was easier to do so because he had earned a Super Bowl ring. “Oh, sure!,” said Madden. “If I didn’t have a Super Bowl ring, I’d still be coaching today.” For fans of the Buffalo Bills, the sting of the four consecutive Super Bowl losses never quite disappears; you do not see all that many “Buffalo AFC Champion” t-shirts, even though no other team ever made it to four straight Super Bowls.

It is understandable that so much is written and discussed about the heartbreaking playoff losses in the ’90s at Arrowhead. But it is worth remembering that they hurt so much precisely because, under Schottenheimer, Chiefs fans rediscovered hope and belief, for the first time in decades.

Sports can transport. And as the first coach I ever truly identified with, Schottenheimer allowed me to see the game through fresh eyes.

The sages tell us it is the journey and not the destination. And at age 57, I have started to notice how often the Buddhist thinkers sound like football coaches. Or maybe it is vice-versa. “Focus… and Finish!,” was one of Schottenheimer’s mantras. He believed in taking it one play at a time. There are worse ways to go through life.