Marriage in the White House

Do we understand a presidency through its policies or through the state of the president’s marriage?

November 19, 2021

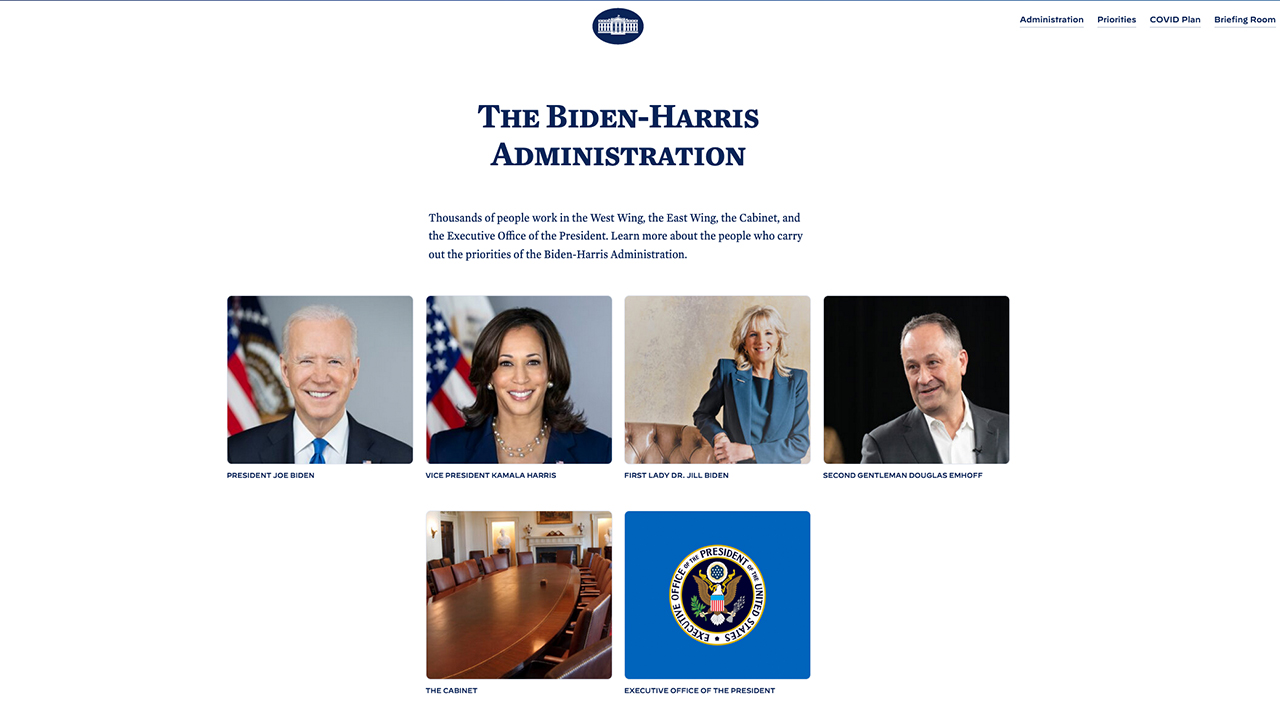

The White House website has four principal tabs: Administration, Priorities, COVID Plan, and Briefing Room. At the top of the “Administration” page are four people, or rather two couples: Joe and Jill Biden, and Kamala Harris and Douglas Emhoff. Below them are “the Cabinet” and “Executive Office of the President.”

It is a far cry from earlier incarnations of the White House website. Constructed in 1994 with a design that now seems crude by any comparison, the homepage included one link for “Executive Branch” and another for “The First Family.”

At first glance, the gallery of these four smiling faces seems so contemporary, a reflection not only of the current President, Vice-President, and their spouses, but also a particular moment in the ways Americans talk about marriage. All this is true, but there is a deceptive assumption at work here as well: that presidential marriages have only recently become the stuff of public discussion, and that presidential spouses have only recently become public figures.

Who can blame anybody for reaching that conclusion? Any discussion of presidential marriages tends to skew toward the recent and either the scandalous or the romantic: the betrayals of Bill Clinton and Donald Trump, the love of Barack and Michelle Obama, the partnership of George and Barbara Bush in shaping a political dynasty.

If the role of marriage in the presidency and the public attention it receives has changed, it is more a matter of degree and of detail than any sort of revolution. Marriage has always been an inextricable feature of the presidency, and in three different spaces: a private and intimate experience of presidents and First Ladies, a public realm in which presidential families have navigated the scrutiny of those around them, and a world of memory in which people have framed both the presidency and marriage by looking at presidential families.

Certain features of presidential marriage are familiar and straightforward, the important and regular stuff of biographies, news media accounts, Beltway gossip, and rumors. The presidency places extraordinary pressure not only on the president but on the president’s family. In some cases, a close and supportive marriage enabled the president and First Lady to withstand the stresses of office. In others, marriages that were dysfunctional from the start became even more frayed in the White House.

Marriage reveals the uncertain degree to which presidents and their families are both private individuals and public figures. It also demonstrates the ways that American politics is never entirely about familiar political institutions, but also a product of culture.

In some cases, a close and supportive marriage enabled the president and First Lady to withstand the stresses of office. In others, marriages that were dysfunctional from the start became even more frayed in the White House.

Understanding presidential marriage begins with a difficult task: seeing beyond either the recent presidents from our own lifetimes and also beyond those most famous presidents (the contenders for top billing on all those lists ranking the presidents) who shape our understanding of the institution. It also means looking beyond the strictly biographical dimensions of individual First Families: Who was happy? Who was miserable? Who betrayed who? And just how weird was it for all this to be happening in the White House?

What follows here is a different account, not of how the presidency helps us understand marriage, but how marriage helps us understand the presidency.

• • •

All living observers of the presidency know that there is a president and a First Lady and that the two are married. They both have public roles and large retinues, and that their private lives are the subject of extensive public discussion.

That story of presidential marriage begins with two seemingly contradictory facts: 1) there has always been a couple in the White House, and 2) not all presidents—or even First Ladies—were married.

Eight presidents were unmarried when they were elected (six widowers and two bachelors). Three presidents (John Tyler, Benjamin Harrison, and Woodrow Wilson) became widowers in office. Two presidents (widower Woodrow Wilson and bachelor Grover Cleveland) were married in office.

The bachelors and widowers never operated alone. When widower Thomas Jefferson brought his daughter, Martha Washington Randolph, to the White House, he announced what would become a commonplace occurrence during the nineteenth century: that there should always be a woman in the White House to support the president.

In the decades that followed, eleven women who were not married to presidents served as First Ladies. They ranged from daughters to nieces to sisters, all of them to one degree or another assuming the roles otherwise reserved to the president’s wife.

Nowhere does the Constitution discuss the First Lady, and yet the presidency has always operated from the assumption that the president is to have a female companion. Even the most withdrawn First Ladies found it difficult to excuse themselves from hosting public events, while more assertive First Ladies—along with the presidents they had married—regularly reminded Americans that most presidents arrived in the White House with a spouse.

When widower Thomas Jefferson brought his daughter, Martha Washington Randolph, to the White House, he announced what would become a commonplace occurrence during the nineteenth century: that there should always be a woman in the White House to support the president.

Consider the case of the first woman to be called “First Lady.” Harriet Lane arrived in Washington in 1853 at the request of her uncle, President James Buchanan. Unmarried throughout his life, Buchanan was the subject of gossip within Washington political circles that questioned his sexuality, and by extension his masculinity. In an office whose all-male occupants have always operated from certain codes of masculinity, Buchanan’s private life was never removed from the public realm of politics. While Harriet Lane did not resolve the political problem facing Buchanan in the absence of a female romantic partner, at least she filled the necessary role of a female presence within the White House.

The absence of marriage was a regular occurrence in the nineteenth-century presidency. It was not gender norms so much as medicine that removed the ambiguous circumstances of presidents who were not married to First Ladies. Since 1915, every First Lady has outlived her husband’s term of office, and most have outlived their husbands after leaving office. Two presidents (Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump) were divorced before coming to office and various unsuccessful candidates have been divorced, but no presidents have become divorced while in office. Single status, divorce, and the loss of a loved one to death have all been removed from the presidency. Instead, for over a century, marriage has been an unshakable presence within the presidency.

Presidential marriage has followed a certain linear progression. It has tracked with prevailing gender norms, and particularly with the fundamental inequalities imbedded in the history of gender and the history of marriage.

Men serving as president wielded political power, controlled family finances, dragged wives and children with them in pursuit of political power. First Ladies operated within a nation where women faced formal restrictions from holding public office and still face lingering doubts about their ability to do so.

While presidents supervised the business of government, First Ladies managed the domestic space of the White House. While presidents met with other government officials, First Ladies organized social gatherings.

Two presidents (Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump) were divorced before coming to office and various unsuccessful candidates have been divorced, but no presidents have become divorced while in office.

First Ladies also did a lot of what would now be called emotional work on behalf of their husbands. And this work was filled with political content. John Adams, James Madison, and John Quincy Adams were all known as irascible characters, and none were ever good at the social schmoozing of politics. They succeeded as politicians in part because Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, and Luisa Adams were adept in exactly those social areas where their husbands struggled.

This was always a delicate balance. When First Ladies met the social obligations of their role but went no further, observers considered the presidential marriage itself to be a success. When First Ladies chose not to do so, the presidential couple faced accusations that they were failing to meet the customs of the office. Conversely, when some First Ladies sought a greater involvement in policymaking, both the president and the First Lady could face intense criticism. Long before critics charged Hilary Clinton with assuming an outsized role during Bill Clinton’s presidency, Edith Wilson faced charges that she had stepped over the line when she became the gatekeeper for Woodrow Wilson following his debilitating stroke in 1919.

• • •

So where was the space for private life within this arrangement? Like the role of First Ladies, privacy proceeded on multiple trajectories at once. At one moment, it is a story of dissolving privacy that will appear familiar to most contemporary observers. But it is also a story of how privacy was created not by the first of most famous presidents or First Ladies, but rather by a later cohort.

Over time, the most seemingly private dimensions of life—health, finances, and intimate relationships—have become less private for presidents. In the early decades of the republic, the most direct scrutiny of presidents and First Ladies came from the political class in the nation’s capital. Mass communication (newspapers, books, and eventually radio) began circulating accounts nationwide. More recently, newer technologies (television, Web-based news and opinion outlets, and social media) provided the public with unprecedented access to married life within the White House.

But this assumption—that presidents lost the privacy they once enjoyed in their private lives, that First Ladies went from invisible spouses to public figures—belies both the shifting nature of privacy within the presidency and the experience of marriage in the White House.

Presidential marriage operated in clumps that responded to the stage of individual relationships and stage of life. The names Millard Fillmore, Abraham Lincoln, and Jimmy Carter are rarely uttered in the same breath, but all three presidents came into office with young children. Likewise, the Reagans and the Clintons may seem light-years apart on political beliefs, but both Nancy Reagan and Hilary Clinton faced similar accusations that they carried too much political influence within the husbands’ administrations.

Put simply, the presidency was not forged in privacy as it operates today, nor would all facets of presidential marriage follow a clear path. Marriage in the presidency was instead created by a strange amalgam of the American plantation and the European court. The majority of American presidents and First Ladies before 1861 were raised in a plantation society in which married life was hardly private. Enslaved African-Americans were a constant presence in the domestic spaces of their masters. Planter couples engaged in conspicuous public displays. John and Abigail Adams, as well as John Quincy and Louisa Adams, may not have come from the plantation South, but their years in European courts during John and John Quincy’s diplomatic careers acculturated them to a world of servants and grand ballrooms, spaces in which married couples underwent constant observation as well as scrutiny, and spaces in which wives participated in social gatherings that advanced their husbands’ public mission.

American presidents (like most of the civilian heads of government that emerged in Europe and the Americas during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) might reject the extremes of public display that marked early modern monarchies. Nonetheless, the cultures and experiences that produced presidents and First Ladies never made them so private as they may now appear.

It took a different type of presidential marriage to imagine a more private life. Presidential couples with different backgrounds (men and women who were not raised on plantations, husbands who worked as attorneys rather than planters, political couples with more experience in state government than diplomatic appointments) pushed back against the assumption that presidents and especially First Ladies needed to be on public display or that First Ladies needed to fill a public role. These are often the forgotten presidents and First Ladies. The likes of Franklin and Jane Pierce, Rutherford and Lucy Hayes, or William and Ida McKinley, include presidents who tend to reside near the bottom of presidential rankings and the couples who have been discarded to the dustbin of collective memory. But they reconstituted presidential marriage, adapting it not only to the experiences they brought to the White House but also to a shifting culture of privacy in the nineteenth century that sought a clearer distinction between home and workplace, one which idealized domesticity as a private space for families.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, presidential marriage would swerve between these two poles, much of it shaped by how much the First Lady and the children of presidents engaged in public events. While Eleanor Roosevelt looms large as an example of how First Ladies could become public figures, she was bracketed by two other women—Lou Hoover and Bess Truman—who disliked public events. And where Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt along with their children were a presidential family on regular display, the Hoovers and the Trumans kept themselves and their children out of the public arena.

In the end, it was one of the most troubled of marriages that would create presidential marriage as we understand it today. The marriage of John and Jacqueline Kennedy established a new mode of presidential marriage, one that constantly and self-consciously put private life on public display for political purpose.

In 1961, John Kennedy joked in a speech that “I do not think it altogether inappropriate to introduce myself to this audience. I am the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris, and I have enjoyed it.” It was not simply that Jacqueline Kennedy played a public role, whether speaking at diplomatic functions or hosting a nationally broadcast television tour of the White House. Those actions reflected not only a change in the role of the First Lady, but also a change in the public presentation of the Presidential Marriage. The Kennedy administration showcased John and Jackie as a romantic couple, as loving parents, and as an effective political team.

Where young children had often kept young presidential couples more detached in the nineteenth century, the Kennedy’s children provided yet another means to establish the image of a presidential family.

Consider this 1963 photo of the Kennedy family vacationing in Hyannis Port. Smiling and casual, John and Jacqueline Kennedy watch their children playing with the dogs, the whole ensemble looking like any other happy family on vacation.

The photo emphasizes the seemingly commonplace joys of family life, obscuring both the reality of Kennedy the president and the grandeur of the Kennedy Compound.

Later presidents would follow that model, whether it was the Ford family on the South Lawn of the White House showcasing the amusing extremes of 1970’s fashion or Barack and Michelle Obama in a moment before a meeting of the diplomatic corps. The Ford family is standing together in every sense of the term. The Obamas are sharing something that only they know, and yet the photograph itself announces that this seemingly private moment provides a public opportunity to shape how Americans understood the Obamas.

In a November 2020 interview, Stephen Colbert joked with Barack Obama that Michelle Obama devoted sixty-three pages to their courtship and engagement in her memoir, Becoming, compared to three pages in Barack Obama’s A Promised Land. “Are you trying to get me in trouble?” Obama joked in response.

This exchange served as a reminder that marriage hardly ceased to frame the presidency after a president left office. Through the memoirs they wrote, presidents and First Ladies continued to paint their own portraits of marriage within the presidency. This was not an easy task. While former presidents had long written memoirs, and a few First Ladies had done so as well, these works all struggled to find a balance between the description of public offices and private lives. Only recently would the presidential couple develop a formula that would bind Republicans and Democrats into a uniform story of marriage before, during, and after the presidency.

Every presidential couple since Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson has produced its own memoirs, and the writings of president and First Lady operate together in lockstep. Both claim to offer a form of intimacy, but of two different types. Presidential memoirs claim to provide a first-hand view of politics and policy. First Lady memoirs claim to provide access to the “authentic” experience of life in the White House. Presidential memoirs discuss actions; First Lady memoirs discuss feelings.

Every one of these books describes the president and First Lady as ordinary Americans in extraordinary circumstances. Regardless of party, region, age, or any other distinguishing factor, there are the same touchpoints: the strangeness of entering the White House, the loss of privacy as a married couple and as parents, the new and highly specific duties facing each of them. George and Laura Bush made this claim, even though George’s family wealth and his father’s presidency hardly made them an “ordinary couple.” Bill and Hilary Clinton did the same, even though they had moved into the governor’s mansion in Arkansas in their 30s and had lived in that public fishbowl for over a decade before Bill’s election in 1992.

And these books together would construct the notion of what the presidency does to marriage. Former presidents and First Ladies alike lament the painful separation from spouse and children. But they also announce themselves as a team, committed to supporting each other surrounded by the piranhas of American politics. It is an assertion of the conventional expectations of contemporary marriage: love and support, mutual respect, a preference for private dignity over public pageantry.

After joking “do you want to get me in trouble?” Barack Obama pivoted to his more serious side, informing Colbert that he had discussed his courtship with Michelle in other books. Perhaps so, but Colbert’s comparison was telling nonetheless. If First Ladies had often done the emotional work—with all its political implications—in the White House, the memoirs of First Ladies have been able to describe an accessible, familiar, romantic dimension to presidents that the presidential memoir does not allow.

These memoirs, and all the interviews that accompany them, portrayed a vision of life after the White House that hammered home assumptions as old as the presidency itself. George Washington’s biographers described him as the modern Cincinnatus, the warrior statesman who surrenders power rather than become a tyrant and retreats to his country estate. George Bush and Ronald Reagan sought to mimic this narrative, both of them retiring to their ranches. Most of Washington’s contemporaries made no reference to Martha Washington in their biographies of the first president, but Laura Bush and Nancy Reagan were central features to the vision of presidential retirement.

The fact remains that the majority of American presidents have sought some sort of public platform after leaving the White House. Some sought elected office, others sought to become arbiters of world peace, others sought to shape national policy and party politics. And yet the conventional story that Americans told about the presidency and that presidents told about themselves was one of retirement in marriage.

Through memoirs and biographies, former presidents and First Ladies, as well as those writing about them, constructed a story of dignified and loving retirement, with a life focused on each other and on family. In some cases, this narrative reflects reality. But it also served to reinforce a central notion of American democracy: that presidents leave office graciously, that they once again become private citizens. In their lives together as married couples with children and grandchildren, presidents and First Ladies are once again just what their memoirs announced: ordinary citizens despite living in extraordinary times.

• • •

Of course, we now know that the wellspring of the modern image of presidential marriage—the Kennedy marriage—was a sham. John Kennedy was a serial philanderer throughout his married life. Jacqueline struggled against the pressures she felt as First Lady.

Yet even that dimension of the Kennedy presidency would become a template of sorts. The realities of the Kennedy marriage would fuel the notion that presidents hide the unseemly details of their private lives and that the type of man who would pursue the presidency would be equally likely to betray his spouse.

During the 1960s and ’70s, Americans became both more critical of their political institutions and more comfortable challenging the claims from public leaders. The Vietnam War and Watergate were the primary political events triggering this change. But public revelations about the Kennedy marriage contributed to Americans’ shifting relationship with the presidency. The notion that Kennedy had lied about his marriage reinforced the notion that he—and other presidents—lied in other ways.

For all their efforts to produce an image of happy marriage designed to reinforce political support, presidential administrations struggled to keep pace both with the release of information and with the shifting cultures of gender and marriage. Subsequent presidents and First Ladies would find that in addition to assumptions of gender that had always shaped Presidential marriage, they faced a new degree of scrutiny. Americans demanded access to intimate details of the presidential marriage, often with an eye toward seeing the presidency itself refracted through that marriage.

. . . public revelations about the Kennedy marriage contributed to Americans’ shifting relationship with the presidency. The notion that Kennedy had lied about his marriage reinforced the notion that he—and other presidents—lied in other ways.

Presidents and First Ladies also struggled to situate themselves within a culture that often was divided about marriage and gender, and there were always plenty of landmines. Pat Nixon and Betty Ford came across as oblivious to the sexual revolution (although Ford would later come to acquire allies who praised her as a feminist). Jimmy Carter sought to advance his image for forthright honesty during his bid for the presidency in 1976 when he admitted that “I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times.” The statement blew up in his face. He drew criticism from both ends of the political spectrum. Others were simply confused by a statement that was both opaque and out of step with the conventional boundaries of the intimate lives of presidents and First Ladies.

As more recent presidents faced the erosion of older norms that had insulated their predecessors both as public figures and private individuals, Americans looked to the past, and specifically to marriage and intimate relationships, to re-consider their presidents. After almost two centuries in which presidents had by-and-large been able to use their marriages as a form of image management, intimate life would become yet another way to interpret—indeed to re-interpret—most presidencies.

Even the most celebrated presidents with seemingly unshakable narratives were not immune. Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings—and the enslaved children produced by that union—would become the focal point of the wholesale transformation of Jefferson’s image from a one-dimensional icon of liberty to a more complex figure who championed freedom while promoting white supremacy. The tragedy of Abraham Lincoln appeared all the more so as the public learned of the emotional struggles that beset both Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. The marriage of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt—long described as a supportive, close-knit team—was in fact a train-wreck.

As presidents and those commenting on them used marriage to do battle over the virtues and failings of any particular administration, marriage remained a ready subject for the ways that novelists, film-makers, and television producers sought to humanize the presidency, as if chronicling the intimate dynamics within the White House somehow granted greater access to the “real” life of presidents.

Not surprisingly, these first attempts would deploy marriage as a way to celebrate presidents. Black and White biopics (Henry Fonda as Young Mr. Lincoln in 1939, Charlton Heston as Andrew Jackson in The President’s Lady in 1953) romanticized presidential marriages, often as a way to establish that personal virtues and romantic heartstrings produced a great president.

Americans demanded access to intimate details of the presidential marriage, often with an eye toward seeing the presidency itself refracted through that marriage.

A series of movies and TV film—Sunrise at Campobello (1960), Eleanor and Franklin (1976), and Warm Springs (2005) —all sought to tell the story of Franklin Roosevelt’s political life through his private relationships. Franklin Roosevelt’s charmed life is disrupted by polio, but with the help and support of Eleanor combined with his unbreakable spirit, he overcomes the trauma of disability, in the process preparing himself for the twin crises of the Depression and World War II. In the end, it took a rather strange movie (Hyde Park on Hudson, 2012) with an unlikely FDR (Bill Murray) to imagine the Roosevelt marriage in all its difficulty.

Film and television relied even more on marriage to tell their stories about fictional presidents. Independence Day (1996) and Air Force One (1997) both imagined the president as an action hero, but also as a caring husband with a marriage founded on romance and respect. The West Wing drew much of its praise from the notion that it was honest and accurate in its portrayal of the presidency. Central to that claim was the notion that President Josiah Bartlet and First Lady Abbey Bartlet had a believable presidential marriage. It did so by duplicating the storyline that former presidents and First Ladies had already created in their memoirs. What made Josiah and Abbey’s marriage accurate? The fact that they struggled with day-to-day problems like competing career goals (Josiah the president, Abbey the doctor), rebellious children, and mounting health problems capped by Josiah’s battle with MS. In other words, they were ordinary Americans in extraordinary circumstances.

• • •

Two recent Presidents—Bill Clinton and Donald Trump—would lay clear the linkages between marriage and the presidency. Both men faced criticism that infidelity within their married lives revealed the limitations of their public lives. Clinton’s behavior revealed his dishonesty; Trump’s behavior revealed his misogyny. Clinton and Trump are now the elephants in the room of any discussion about marriage and the presidency. Meanwhile, some of the best writing about marriage and the presidency concerns these two presidents.

For those reasons I have opted to keep them at the edge of the story, to see their presidencies as products of two centuries in which marriage shaped the presidency, rather than the wellspring for any discussion of presidential marriage.

It turns out that two of the presidents who Americans tend to know nothing about actually have a lot to say about marriage, the presidency, and the line between politics and privacy. And with that, we need to consider the case of the Grants and the Hardings.

The story of Ulysses and Julia’s books shows how far presidents and First Ladies have moved, as marriage has gone from the periphery to the center of the story for these political figures.

Julia Dent and Ulysses Grant married in 1848 despite the disapproval of both their fathers. By the time he became president in 1873, Ulysses Grant had written repeatedly about how much he loved his wife and children and how painful it was for him to leave them. As First Lady from 1869-1877, Julia worked actively alongside Ulysses, a public presence in Washington who, as hostess, helped sustain the social links of Grant’s political network.

In 1884, Ulysses was diagnosed with throat cancer, a death sentence considering the state of nineteenth-century medicine. Broke and desperate to provide for Julia, he accepted a contract to write a memoir. Ulysses completed the manuscript within days of his death in 1885. The result was a sprawling and masterful work, the first true presidential autobiography. Yet in all two volumes and nearly 1,200 pages, one struggles to find the Grant marriage or the person of Julia Dent Grant.

Julia Grant’s memoir followed its own tortured path. Initially reticent to do so, Julia eventually wrote a manuscript, but died before it was published. It was the first memoir manuscript written by a First Lady, but was not published until 1975, by which point Julia Grant’s successors were just developing the customary rules of the First Lady’s memoir.

The story of Ulysses and Julia’s books shows how far presidents and First Ladies have moved, as marriage has gone from the periphery to the center of the story for these political figures.

When Warren Harding was elected President in 1920, he famously promised a “return to normalcy,” namely that the United States would return to a politics and culture that predated the upheavals and internationalism of the early twentieth century. Yet Warren’s own marriage was hardly “normal” within the idealized assumptions of the presidency. His wife, Helen, had been divorced. Meanwhile, Warren conducted a pair of extramarital affairs, the second of which, with Nan Britton, produced a series of love letters whose erotic content is all the more startling next to Warren’s staid, conservative public image.

The letters of Warren Harding and Nan Britton were only recently made public, and in the discussion that followed, we see presidential marriage as it operates today. Intimate details can and should be in the public domain. Harding’s marital deceit embodies the corruption that enveloped his administration in the Tea Pot Dome scandal. Helen was forced to endure the betrayal within an institution that liberated men and restrained women.

Joe Biden has implicitly made his own claims of a return to normalcy after the Trump administration. First among these was to restore the norms of the presidency, in all its forms. And presidential marriage is one of those norms. Where Donald Trump betrayed all three of his wives, Joe Biden’s story was one of love tragically lost with the death of his first wife and love reborn in the marriage to his second. Where Melania Trump seemed emotionally inauthentic and disconnected, Jill Biden has conspicuously conducted the First Lady’s emotional work. When Jill Biden told Joe Biden to “Pay attention!” during a speech in June 2021, she added to the Biden White House’s careful campaign to portray a marriage based on good humor and mutual respect. That campaign is all the more important after Biden faced accusations during the campaign ranging from inappropriate physical contact to sexual harassment to sexual assault.

. . . for all these claims to the new, presidential marriage remains what it has always been: a job for president and First Lady with clearly defined roles, a relationship that presidential administrations use to build political support, and a subject that can just as easily be turned against the president.

The First Lady is publicly referred to as Dr. Jill Biden, an ongoing reminder that she has her own life, her own career, and her own accomplishments separate from those of the President. But on the White House website, Joe and Jill Biden are a team, together with Kamala Harris and Doug Emhoff. These four are, at one moment, the vision of a new presidency: a First Lady who has continued her teaching career, a female Vice-President of color in an interracial marriage, two blended families with children from prior marriages that ended by death and divorce.

Yet for all these claims to the new, presidential marriage remains what it has always been: a job for president and First Lady with clearly defined roles, a relationship that presidential administrations use to build political support, and a subject that can just as easily be turned against the president.

Across more than two centuries, marriage would be a crucial feature of the presidency as a political office. It became a barometer that people used to assess their presidents even as presidents and First Ladies deployed marriage for their own image-making purposes. This was the case because the presidency has never been an exclusively political institution, but rather a cultural institution that Americans deploy to address innumerable concerns that often extend well beyond the strictly political. Marriage and the presidency are no exception.