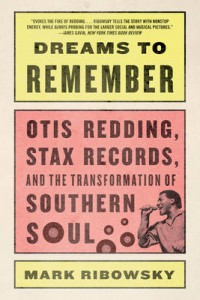

Like all biographers, Mark Ribowsky trades in legends. His earliest biographies focused on Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige, the two best ballplayers in the history of the fabled Negro Leagues. Since then, Ribowsky has chronicled pop-culture icons of the 1960s and 1970s: larger-than-life sports figures like sportscaster Howard Cosell, Oakland Raiders owner Al Davis, and Dallas Cowboys head coachTom Landry; and chart-topping musicians like Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Supremes, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, and producer Phil Spector. His latest book examines Otis Redding, the soul singer who was the face of Memphis-based Stax Records from 1962 until 1967, when he died in an airplane crash at age 26. In the Redding biography, entitled Dreams to Remember, Ribowsky hails the singer as the voice of the 1960s generation, “a prophet and a poet” who captured the hearts of young people on both sides of the color line. According to Ribowsky, Redding’s music spoke to the “angst and loneliness” of the baby boomers, who were “finding [their] way beyond the racial and political conditioning of [their] forebears.” Ribowsky believes that Redding was able to connect with young listeners because he too was broken-hearted and blue, and Dreams to Remember is framed as an answer to the question “[w]hy was [Redding] so lonely and alienated?” “This mystery,” Ribowsky writes, “has never been satisfactorily resolved.” Nor will it ever be. Ribowsky’s “mystery” is based on false assumptions, and attempting to solve it will lead only to misunderstanding Redding and his music.

Plenty of research went into Dreams to Remember. Ribowsky consulted three previous Redding biographies (by Jane Schiesel, Scott Freeman, and Geoff Brown), interviewed nine of Redding’s colleagues, and read hundreds of press clippings. But few, if any, of these sources support Ribowsky’s contention that Redding was burdened by a “cleaved heart.” In fact, those closest to the singer say just the opposite. Redding was a joy to be around, always eager to lift the spirits of his friends and family. He was beloved by everyone at Stax Records, from the executives and staff musicians to the secretaries, and as his celebrity grew, he became a favorite son in his hometown of Macon, Georgia. If the singer did indeed have a “tortured soul,” as Ribowsky asserts, no one knew it—not even Redding.

Ribowsky tries to bolster his claim by subjecting Redding to armchair psychoanalysis. According to Ribowsky, the singer was constantly afflicted with “pain and despondence”: “Clinically, much of this seemed clearly to have swelled as the result of his difficult relationship with [his father] Otis Sr.” Redding’s father was a Baptist deacon and church musician. With his father’s encouragement, Redding began singing in churches, studying the piano, and playing drums. He was also drawn to rhythm and blues music, and during his teen years he visited Macon nightclubs to hear sets by local legends Little Richard and James Brown. Soon Redding decided to become a professional rhythm and blues singer, an ambition that his father did not support at first. However, when Redding’s career took off, his father relented, and the two men repaired their rift: Redding Sr. even moved into a house on “The Big O Ranch,” the singer’s 300-acre farm near Macon.

Ribowsky’s misconception is understandable—almost. For more than a hundred years, outsiders have portrayed African American music as the product of unbridled emotion and raw physicality. Dreams to Remember revives this myth, exhuming turn-of-the-century myths about blues and jazz and applying them to 1960s soul music.

In addition to psychoanalyzing Redding’s paternal relationship, Ribowsky scrutinizes the singer’s marriage to the former Zelma Atwood, the mother of his three children. The couple married young, and at times their relationship was strained by Redding’s busy tour schedule and episodes of infidelity. But by all accounts, they overcame these early difficulties and formed an unbreakable bond that was a comfort to both husband and wife. Ultimately, the analysis of Redding’s marriage does not yield the psychical clues Ribowsky is seeking. So he turns to the singer’s performances and recordings, the last remaining pieces of evidence for the thesis of Dreams to Remember—that “Redding’s rare ability to make a heart hurt can only have been because his own was so breakable.” According to Ribowsky, album titles like Otis Blue and Pain in My Heart are proof positive of Redding’s emotional state, an unrelenting despair which somehow remained hidden until the moment he began to sing. “[Redding] was too comfortable with the blues,” Ribowsky writes, “and while that was good for business, even the big, blustery, carefree front he could easily unfurl … could not make his diffused burdens go away for long. Certainly, the … surfeit of pain in his songs reflected anything but carefree amusement.” In other words, the personality that endeared Redding to his family and friends was an illusion. The singer only revealed his true self, Ribowsky claims, when he was on stage performing for an anonymous audience.

Ribowsky’s misconception is understandable—almost. For more than a hundred years, outsiders have portrayed African American music as the product of unbridled emotion and raw physicality. Dreams to Remember revives this myth, exhuming turn-of-the-century myths about blues and jazz and applying them to 1960s soul music. To Ribowsky, Redding’s romantic ballads are “pain-streaked confessions,” while his uptempo tunes are virtually orgasmic: “tribal dances” of “writhing,” “milking,” “spitting,” and “exploding”—until his audience is left “stunned and damp.” (Moisture is a recurring theme in Dreams to Remember. Ribowsky has an odd habit of describing the singer’s audience as “damp”; odder still, his favorite adjective for Redding is “sweaty.”)

Why is Ribowsky so convinced that Redding was “a soul man unhappier than he had a right to be”? The most charitable explanation: Ribowsky loves the singer’s music so much that he forgets Redding was a performer. Redding learned to sing in the African American church, and he refined his craft on the old “chitlin’ circuit.” These experiences taught him how to use every tool in the performer’s arsenal—the voice, gestures, dance, even his stage attire—to convey the total meaning of a song, transforming music and lyrics into gripping drama. As Albert Murray and Paige McGinley have argued, many music genres are highly theatrical, none more so than gospel and blues, the styles at the core of Redding’s music. And just like a dramatic actor, Redding did not have to feel miserable himself in order to tug at the audience’s heartstrings. He was a masterful exponent of the rhythm and blues tradition, in which each aspect of a performance is precisely calibrated to deliver the maximum emotional impact. If Ribowsky feels a sense of catharsis after watching Redding perform “Try a Little Tenderness,” he should resist the impulse to question the singer’s emotional stability and instead applaud him for a job well done.

Ribowsky’s faulty psychological diagnoses are not the only myths in Dreams to Remember. The author is so committed to his vision of Redding as an Aquarian messiah—bearer of the baby boomers’ youthful burdens—that he depicts nearly all of the singer’s music-industry rivals as imposters and scoundrels. One of Ribowsky’s favorite targets is Motown Records, the label that was Stax’s biggest competitor on the rhythm and blues charts. Motown singers like Smokey Robinson were “big-city cool,” while Redding and his fellow Stax artists were “sweaty, Deep South church pulpit hot.” In Ribowsky’s view, record labels specializing in black music ought to make their studio sessions “as real and sweaty as possible.” If a label interferes when African American singers are attempting to release their pent-up emotions, the resulting recordings will be inauthentic—that is, not “black” enough. It is from this perspective that Ribowsky criticizes Motown’s strategy for producing crossover hits: “[Motown] built a strict producer-centric caste system in order to distill the blacker edges of blues-based music to expressly appeal to the white market, [but Stax] just let fly whatever came from the studio, where anyone could have a say in the production. As a result, the sound coming from [Stax’s] studio was blacker than the famed, heavily formulaic ‘Motown sound.’” Some Stax musicians liked to pretend that their all of their songs were recorded live with no overdubs, unlike Motown, and Ribowsky is happy to echo their critiques of Motown recordings as “mechanically done.” He must hope that his readers will overlook the inconsistency that emerges a few pages later when he quotes Stax executive Al Bell’s detailed description of the overdubbing procedures favored by Redding, who preferred to record the rhythm section first, followed by the horn section, and finally the lead vocals.

While writing Dreams to Remember, Ribowsky must have worn out his thesaurus’s entry for “bad guys.” Label owners and other industry professionals are attacked mercilessly, each insult more ridiculous than the last: “record industry lice,” “cigar-chomping sharpies,” “corporate thieves” and—the clincher—“Lucifer incarnate.”

The antipathy for Motown in Dreams to Remember will shock readers who know Ribowsky’s three books about Motown artists (the Supremes, the Temptations, and Stevie Wonder), in which his treatment of the label is much more even-handed. But the most jarring aspect of the present biography is the incessant vitriol that Ribowsky directs at the entire music industry, a faceless bête noire that he accuses of “abusing” Redding at every turn in the singer’s career. While writing Dreams to Remember, Ribowsky must have worn out his thesaurus’s entry for “bad guys.” Label owners and other industry professionals are attacked mercilessly, each insult more ridiculous than the last: “record industry lice,” “cigar-chomping sharpies,” “corporate thieves” and—the clincher—“Lucifer incarnate.” In unhinged passages like these, most readers will find it difficult to take Ribowsky seriously. And perhaps he wants his readers to bring a healthy sense of irony to Dreams to Remember. After all, Redding himself was active on both sides of the music industry. By 1967, he owned a music-publishing company and was producing records for other artists, while his longtime business partners were managing dozens of Southern rhythm and blues acts. If Redding had lived a few more years, his music-industry enterprises would have continued to expand, endangering Ribowsky’s idealistic image of the singer as a hero who never “[sold] his soul, or [sold] out soul, for a formulaic hit.”

Dreams to Remember is not without its redeeming features. Redding fans may appreciate Ribowsky’s enthusiasm for his subject. Also to Ribowsky’s credit, the book is less inflammatory than Scott Freeman’s 2001 Redding biography, which was so sensational that it became the subject of a libel suit. However, readers looking for new insights about Otis Redding and 1960s soul music should leave Dreams to Remember on the shelf.