The house in Washington, D.C., where I lived as a child was up the street from that of my friend Trevor Sampson. When I was in first or second grade, Trevor’s family arrived from South America—to this day I do not know which country—and Trevor spoke with an accent that, while not preventing him from finding a place among the other brown-skinned kids in our neighborhood, definitely marked him as different. His family stood apart in other ways, too. One Labor Day I went to Trevor’s house to see if he could hang out, but he could come no farther than his front porch, because his family was committed to watching Jerry Lewis raise money on his annual muscular dystrophy telethon. I do not recall what we talked about on his porch; all I remember is the moment when his mother poked her head out and said to Trevor with a huge smile, “They got twenty-one million.”

That story, when I tell it in person, never fails to get a laugh, one that I am not sure is at the Sampsons’ expense. What was peculiar, after all, was not some custom the family had brought with them from elsewhere, but the one they latched onto when they got to D.C.; the Jerry Lewis telethon was as pure a piece of Americana as ever there was, and in laughing about it, we—whoever “we” are—laugh about ourselves. Whatever foreignness or otherness led the Sampsons to watch the telethon, to be so utterly, blatantly square as to embrace such mainstream, popular, big-hearted dorkiness, also showed that they fit right in. If the Sampsons were set apart, they should not have been. That idea was illustrated, too, by a name we D.C. kids never tired of calling each other. “Bama” meant a clueless, badly dressed, or otherwise uncool person, though nobody knew why it meant that, as was demonstrated when, on my high school’s “Bama Day,” for which everyone showed up wearing out-of-style or unmatching clothes, nobody could agree on how to spell “bama.” As seems obvious in retrospect, the term was short for “Alabama,” or a person who had (however long ago) brought his unhip country ways to the city, and there were enough of those poor souls around to make the insult common. To put it another way: everybody in D.C.—a majority-black city in those days, if not now—was from somewhere else. We (or our parents) had come to Washington, which was south of the Mason-Dixon Line and yet represented a spiritual North for those seeking opportunity, or refuge, or a second chance.

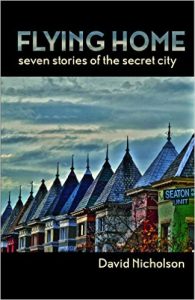

Being from somewhere else is a condition common among the characters of David Nicholson’s wonderful, rich collection, Flying Home: Seven Stories of the Secret City. “Somewhere else” may be a physical place—the West Indies in the case of “Gettin’ on the Good Foot,” America’s Deep South in “Among the Righteous” and “Seasons”—or it may be a lower socioeconomic class and its attendant emotional landscape, as in the title story, in which a successful man and his teenage daughter encounter a down-and-out woman the man knew in his youth.

The stories themselves gaze back at the past—the 1960s and 1970s—a time before gentrification, before U Street Northwest had or needed a tanning salon, a time when, if the symbols of national government made up the city’s shell, working-class blacks were its heart.

Wherever they are from, though, these black characters are now in Washington, the “Secret City” of the subtitle, secret because the lives and struggles unfolding on its streets are far from “the Capitol and the distant white icons of the monuments,” which constitute “what people who visit from other places think is Washington,” as the narrator of “Saving Jimi Hendrix” puts it. Sometimes the characters’ struggles involve finances; often they concern the wariness or actual distrust between men and women or the negotiations and disillusionment that characterize long marriages; many times they are about having been betrayed or having betrayed someone, purposefully or not; occasionally they include characters’ wistful or regretful thoughts about the past; in some instances they touch on the limits of fathers’ ability to protect their children; and, always, they are communicated in the Southern or island speech of these men, women, and children, lending a local flavor to the stories’ universal themes. The stories themselves gaze back at the past—the 1960s and 1970s—a time before gentrification, before U Street Northwest had or needed a tanning salon, a time when, if the symbols of national government made up the city’s shell, working-class blacks were its heart.

And the flavor of D.C. includes the city’s other sounds, too—the cicadas of its summers, snatches of TV shows heard through windows—as well as its look, smell, and feel. In the first story, “Gettin’ on the Good Foot,” the only one of the seven with a young protagonist, Nicholson does an especially fine job of capturing the city through the senses, wisely using childhood—that time of idle, sharp, indelible observation—as a lens:

Halfway down the cracked concrete steps to run an errand for his mother, Neville stands transfixed. It’s like looking up from the bottom of a pool of clear, pristine water. Later, the heat will become almost audible, a soft, whirring insect whine, and only those with someplace to go—or no place at all—will brave the afternoon. Sounds will seem to come from far away, dim voices from radio or television, fragments of conversation, a child crying, a screen door slamming. But now, heartbeats before the rude slam of a screen door disturbs the morning stillness, the liquid air makes the world new again.

Neville, who has moved with his family from Freeport, faces that classic young immigrant’s dilemma: trying to fit in while facing psychic pressure from his parents if he does so too well. His father tells him, referring to Neville and Neville’s friend, “You changin’ right before me eyes. I lyin’ upstairs listening, and I can’t tell which onea you talkin’. You sounding like a regular little American.” Neville tries to navigate the codes and trends among the boys his age in the neighborhood (who is this James Brown, anyway?) and struggles to understand the behavior of his adult neighbors, particularly the way they talk and act when romance is involved. The boy’s parallel concerns converge in a heartbreaking manner at story’s end.

From a pure storytelling standpoint, “Good Foot” is the most successful piece in Flying Home, with an ending that is both surprising and perfectly logical, seemingly even inevitable, given elements that were skillfully set in place from the beginning. A couple of the other stories, by contrast, are like fascinating psychological studies in which Nicholson has skewed the data ever so slightly to get the results he wants. The daughter’s line to her father at the very end of the title story, for example, seems to come less from the character the writer has created than from the point he wants to make; the same could be said of an exchange between the long-married husband and wife late in “Seasons.” The ending of “A Few Good Men” has the opposite problem: Some characters catch on to the revelation about one of the barbers while others miss it, but they all lag behind the reader.

Love is depicted as a species of negotiation that sometimes breaks down into armed conflict; marriage resembles a kind of long-term embrace/wrestling match in which one’s struggle to subdue the other is indistinguishable from the effort to hold on for support.

Those same stories, however—“Flying Home,” “Seasons,” “A Few Good Men”—are also examples of Nicholson’s considerable strengths, chief among them, perhaps, his ability to capture the texture of daily life among his D.C. folks. In “Flying Home,” when the main character lets the down-and-out woman from his youth into his car, the reader can hear her voice—“Least lemme ride witchu”—just as “the smell of sweat, wine, and urine” fairly waft from the page; in “Seasons,” an aging onetime Negro League pitcher tells a rapt young boy, not for the first time, about his glory days, the cadence of his voice evoking the heat of the park and the sound of the ball landing deep in a leather glove. “A Few Good Men” is set in a barber shop, that black male port in a storm, where the voices of the owner, the two other barbers, and the customers trade fours and build on one another, call and respond like the reeds, brass, drums, bass, and piano in a performance by that hometown boy Duke Ellington’s band:

“And then?” Doc says as he approaches the chair. “What happened next?”

“Whatchu mean, ‘what happened’?”

“I mean what happened? It didn’t just end that way. What happened?”

“Whatchu think happened? Wasn’t but a couplea days after he put the house in her name, Carver come home and found two suitcases on the porch. Key didn’t work ’cause she’d done had the lock changed …”

The subject, of course, is women—how you have got to treat ’em, how they will treat you if you are not careful, just look at how such-and-such’s woman did him. In most of the stories, the theme of male-female relationships is strongly present if not front and center. Love is depicted as a species of negotiation that sometimes breaks down into armed conflict; marriage resembles a kind of long-term embrace/wrestling match in which one’s struggle to subdue the other is indistinguishable from the effort to hold on for support. The husband and father in “Among the Righteous” dreads telling his “hard-headed woman” about losing his job of seventeen years, then resists her advice for getting it back, while the wife in “Seasons” considers what she gave up long ago out of desire for her longtime husband, desire that has turned to ashes.

That kind of regret is practically a character in some of the stories. Nicholson’s D.C. residents have come from all over, but where they have all come from is the past, which lives on in their minds as a place where things might have gone differently. That theme ties the last piece in the book to the others, from which it is otherwise very different. I write “piece” rather than “story” because “Saving Jimi Hendrix” is, or at least takes the form of, a personal essay; it begins with a fantasy on the part of the book’s only first-person narrator, a fantasy that involves, well, saving Jimi Hendrix—preventing his real-life fate of choking on his own vomit at age 27 and letting him flourish musically for decades more. From there, Nicholson (or his narrator) ruminates engagingly on his own youthful experiences as a music fan growing up in D.C., in a time when his explorations of different genres (blues, rock, soul) paralleled his shuttling between black and white friends, “passing from one world to the other and feeling comfortable in neither.” (Nicholson’s narrator attended school at the prestigious, mostly white Sidwell Friends.) Hendrix’s music suggested—much the way Ralph Ellison’s writing did, as Nicholson would later discover—“the possibility for a kind of freedom that transcended definitions laid down by others.” If only, if only, Hendrix could have kept playing.

Nicholson’s D.C. residents have come from all over, but where they have all come from is the past, which lives on in their minds as a place where things might have gone differently.

But for Nicholson’s characters, regret tends to give way eventually to resignation, from which, in turn, grows acceptance. Seen from this point of view, “Carolina Is Dancing,” the fourth and by far the shortest of the seven stories—a kind of interlude—captures the spirit of the book. Carolina, with her “stick legs in mesh stockings,” dances in a bar for customers who have come hoping to see another dancer, Lola. The customers may be disappointed, but they will have to make do.

Nicholson is a product of both the University of the District of Columbia and the Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa—which must make him rare, if not unique—and has served as an editor and reviewer for the Washington Post Book World as well as the founding editor of Black Film Review. He has also worked for the San Francisco and Milwaukee bureaus of the Associated Press. Flying Home is his debut collection.

And it is a fine one: a heartfelt, sympathetic portrait of a slowly vanishing world. For readers who are new in town, this volume is a tour through a Washington they will not learn about in any guidebook. For others, reading this collection is like, yes, flying home.