Nat Hentoff arrived at the right place at the right time, albeit “out of step.” Born in 1925, “Boston Boy” came of age during the bebop revolution after World War II and established himself as the most influential jazz critic during the Golden Age of jazz in the 1950s and 60s, the Age of Charlie Parker, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Abbey Lincoln, Bud Powell, Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, and others. (Only Rollins survives now: perhaps tellingly the victim of a recent failure at satire in the New Yorker.) Today’s jazz critics debate whether jazz itself survives and, if so, whether it has become museum music in the hands and heads of numerous graduates of jazz degree programs. Hentoff’s “Final Chorus” closed each issue of Jazz Times from February 1999 through February 2012 before Hentoff, never a stranger to controversy, left over creative differences. It is not surprisingly ironic that he wrote his last jazz columns for this magazine, the rival of DownBeat, which he solidified as its New York editor more than 50 years ago.

Hentoff’s parallel rocky path led him to a weekly column on American social and legal history in the Village Voice from 1957 until he was “laid off” in December, 2008. He also wrote extensively for the New Yorker and Playboy. In 2009 he joined the libertarian Cato Institute as a senior fellow, and he has continued to write a column for WorldNetDaily.com. In a tribute to Hentoff in the credits of The Pleasures of Being Out of Step, David L. Lewis assures viewers, “He still writes everyday, and he still pisses people off.”

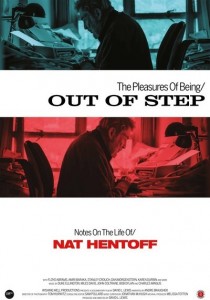

This documentary profile of the famed and feisty Hentoff had its world premiere in 2013 at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival sponsored by the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. According to a recent post on the film’s Facebook page, Pleasures is currently one of 134 new documentary films to qualify for Oscar consideration. The film has been shown at several film festivals, including Cinema St. Louis’s International Film Festival in November, 2013. It was released in DVD format sometime early in 2015.

Pleasures cuts briskly but evenly between Hentoff’s jazz life and his political life; in fact, the film insists that ultimately these lives are of course one and the same, focused intensely and abidingly on the individual’s right of free expression. Hentoff’s fellow jazz writers such as Dan Morgenstern, Stanley Crouch, and Amiri Baraka praise his unfettered knowledge of and devotion to the music and the musicians, particularly the turbulent work and life of the bassist and composer Charles Mingus, who regarded Hentoff as one of the few white men he could trust. Hentoff’s reviews and his detailed and incisive liner notes of jazz albums set a high standard for his colleagues and affirm his wife Margot’s assessment of him as “a teacher through his writing.” (She also provides the epithets in the title of this review.)

Pleasures cuts briskly but evenly between Hentoff’s jazz life and his political life; in fact, the film insists that ultimately these lives are of course one and the same, focused intensely and abidingly on the individual’s right of free expression.

Like his more seasoned contemporaries Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff at Blue Note Records, this son of Jewish immigrant parents—all “outsiders,” as Baraka says in the film—identified with African-American musicians and for at least two years in the early 1960s produced about 40 jazz albums for Candid Records, by avant-garde artists such Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, Eric Dolphy, Cecil Taylor, and Mingus. Roach’s “We Insist!”, subtitled “Freedom Now Suite,” was one of those albums, famous now not only for its music but also its notoriety in being banned in South Africa. Jazz fans of today might not realize that Hentoff was creative director of The Sound of Jazz, broadcast on CBS TV in 1957, an elegant but unadorned exposition of some of the music’s greats, including Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Monk, and Holiday, performing live in a studio.

Hentoff’s disquisitions on First Amendment issues and cases are more widely and infamously known than his contributions to jazz. In 1977, when the National Socialist Party of America announced its intention to march through the Chicago suburb of Skokie, a predominantly Jewish community, Hentoff defended its right to do so. In the film a woman who was 16 at the time, speaks of her outrage at Hentoff, whom she had admired for his jazz writings. Yet after writing to him, she received a lengthy letter in return and a patient, detailed explanation of his position on Skokie, which, she states, taught her what she now reveres about the Constitution. (Ultimately, the march never happened.)

In the mid-1980s, Hentoff departed from his wife’s and many women friends’ beliefs in a woman’s right to an abortion as part of her fundamental right to privacy and control over her body. He had become curious not only about the case of Baby Jane Doe, a Long Island infant born with spina bifida, and fetal surgery that can allow babies with the condition to grow up as productive adults, but also the press coverage the case received. Hentoff wrote, “When I see that kind of story, where everybody agrees, I know there’s something wrong. I finally figured out that they were listening to the parents’ lawyer.” His essay, “The Awful Privacy of Baby Doe,” was published in The Atlantic, and Hentoff then became the “Champion of ‘Inconvenient Life.’” Hentoff added later, “The ‘slippery slope’ business began to make sense to me then. From there it was ineluctable—not just abortion, but euthanasia as well.”

David L. Lewis published a companion volume to his documentary film, The Pleasures of Being Out of Step: Nat Hentoff on Journalism, Jazz, and the First Amendment: An Oral History” (CUNY Journalism Press, 2013). Fans of Hentoff will find the book an essential, irresistible read. Half the interviews in its chapters are devoted to jazz and half to “Civil Rights” and “Political Battles,” and Hentoff himself gets the best lines. The form of the book echoes Hentoff’s renowned book of interviews of jazz musicians, Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya: The Story of Jazz As Told by the Men Who Made it (with Nat Shapiro, Dover, 1955). Mingus praised Hentoff for “digging the meaning of the questions” he asked, and Lewis, a reporter, television news producer, and journalism professor, follows suit.

Music lovers will appreciate the film’s soundtrack, which is made up of seminal selections by some of jazz’s greatest artists. Margot Hentoff says of her husband, who is approaching 90, “He reads and he writes. That’s all that he does.” Hentoff himself says, “I write to write.” The film’s credits close with a track on trumpeter Booker Little’s Candid album, “Out Front,” and this plaintive tune is dedicated to Nat Hentoff. The title is “Man of Words.”