Like most viewers of episode five of Ryan Murphy’s FX series Feud: Capote vs. the Swans who knew that time, a meeting between James Baldwin and Truman Capote? I was astonished.

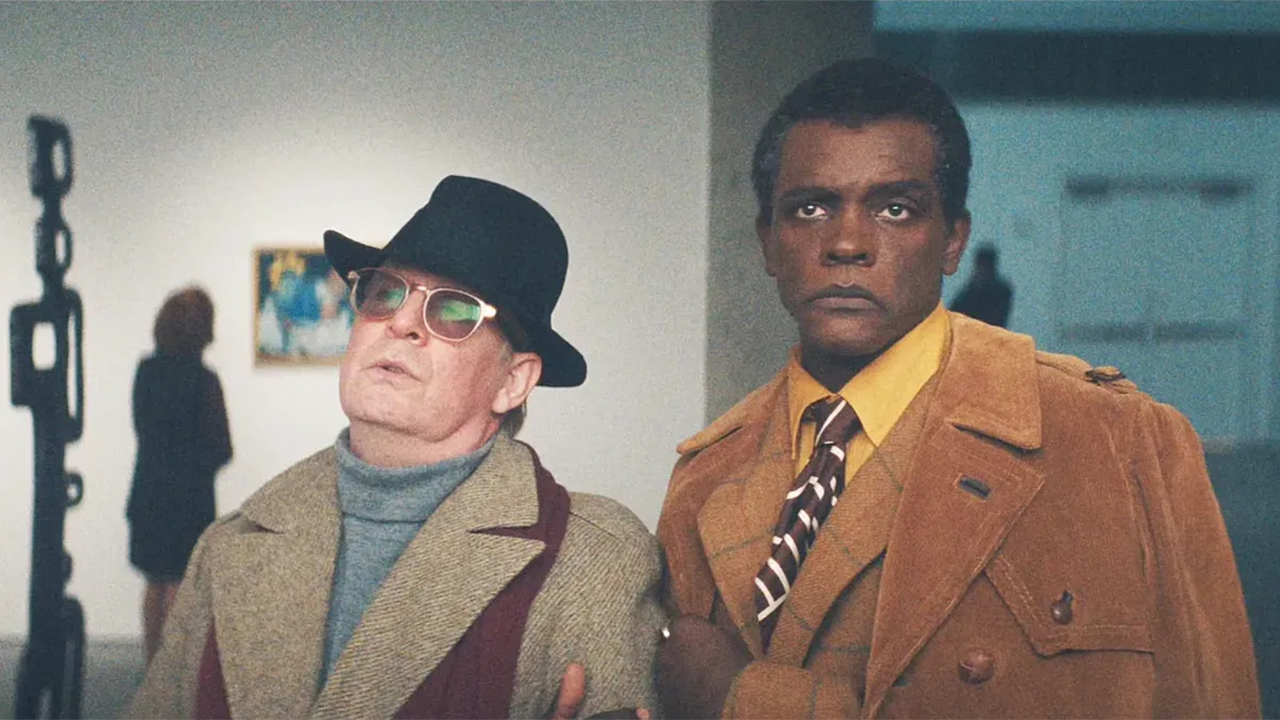

Tom Hollander’s portrayal of Capote was brilliant, and Chris Chalk’s embodiment of Baldwin was believable and riveting.

This particular episode takes us back to 1975. Capote has just published a fictionalized account of the scandal between Babe Paley and Slim Keith, and as a result, Capote has been ostracized, and fallen into writer’s block, soothing his pain with pills and alcohol. He gets a call from his old friend, James Baldwin, who drags Capote back into the world.

Baldwin is hell-bent on getting Capote over his writer’s block. In the course of the evening, Baldwin gets Capote to admit he is a racist. And at the end of the episode, Capote has some insight into his dilemma and can begin writing again.

Critics seized on the improbability of the episode. Fletcher Peters of The Daily Beast denies that it could not have happened in real life. The actor, Chris Chalk, claims that he was not interested in the actuality.

The American media does not have much information about the lives of Truman Capote and James Baldwin. Even literary critics, who reviewed the episode, have very little information about James Baldwin, who lived in Europe most of his life.

Baldwin is hell-bent on getting Capote over his writer’s block. In the course of the evening, Baldwin gets Capote to admit he is a racist. And at the end of the episode, Capote has some insight into his dilemma and can begin writing again.

The circle of writers included Baldwin and Capote, as well as Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow, James Jones, Terry Southern, and many more. If we had more understanding of literary art in itself, we would not be so ready to misunderstand the relationship between Capote and Baldwin.

I met Baldwin in Paris, in the summer of 1973. I met Capote in Key West, Florida in 1975, a few months before Esquire published “La Côte Basque, 1965” that November.

My French publisher had invited me to Paris to work on the translation of my 1969 novel, The Life and Loves of MR. Jiveass Nigger into French. (The word nigger was not a problem with the French—it was the word “jive” that threw them.)

Before Baldwin and Capote became famous, the American colony was scuffling. They were poor and broke—and friends. Jimmy, as I came to call Baldwin, wanted me to know that, and being a country farm boy from North Carolina, he found in me an apt student.

They learned to survive as writers, as artists. Jimmy became very much the type of person who would remind his friends that they were important simply because they were writers! No matter how bad things get, you have got to remember you are a writer!

So in the television episode, I found it very believable that Jimmy would do for Capote what he had done for me and many others.

The education Jimmy laid on me involved taking me to cafés in Paris and talking about people he knew back in the days when life in Paris was tough on American expatriates. He took me to meet James Jones, author of From Here to Eternity (1951), who threw a weekly party in his villa on Îsle Saint-Louis, where I heard stories about other writers who survived the second American colony.

… I found it very believable that Jimmy would do for Capote what he had done for me and many others.

At the end of the summer, I went down to the south of France, to St-Paul de Vence, to visit Baldwin. There I heard more stories about the American colony when they were really broke. I heard more stories about Capote from Jimmy and his friends. In the Feud episode, Baldwin asks Capote, “Why didn’t we become lovers?” I heard this differently. Jimmy dismissed jokes about trying to pick Capote up, laughing and saying that Capote was too “paternalistic.”

I came back home to Berkeley in 1974. I went across to San Francisco and talked to Jann Wenner, the Berkeley dropout who had recently started a magazine called Rolling Stone. I convinced him to send me to New Orleans to interview Tennessee Williams.

Wenner asked me if I knew Williams; I “knew” his “writing,” and had read all of his work. He asked me where Williams lived. I said in the Garden District in New Orleans. With that, he assigned me the interview. When I got to New Orleans, I did not have an address for Williams. I walked around the Garden District asking people if they knew where Tennessee Williams lived.

I met a bookseller who pointed me to the house where Williams lived. When I knocked on the door, the guy who opened the door, said “Mr. Williams, he is in his other house.”

I discovered that his “other house” was in Key West, Florida. I got on the phone and told Jann that they had to send me to Key West. When I got to Key West, Williams opened the door, somewhat perplexed. He had a telephone in his hand. “My agent told me that I shouldn’t talk to you… come on in. I will give you an interview!”

The interview should have taken only a day but Williams and I got along so well that I extended it to a week. Williams was basically a poet and I was a lover of his favorite poet Hart Crane. He also loved Shakespeare, and I spent a year at Columbia, studying all Shakespeare’s poems and plays. We would get high on good wine and cite passages from Shakespeare.

When I went back to the hotel that first evening, I discovered that the hotel was full of writers and actors because someone was making a movie starring Peter Fonda. Jim Harrison, the novelist and poet, was also living there. The word had gotten out that there was a writer from Rolling Stone there to interview Williams.

As it turned out, Williams was a local celebrity. Everybody knew who he was, but he was a bit of a recluse, and nobody would go over and talk to him. Tennessee liked nothing better than going to lunch with me where we were in view of other people who did not dare to come up to him and lollygag.

I also met Jimmy Buffett, the singer, who had a big yacht parked out in the Atlantic. Just as I stumbled upon the American colony in Paris, here was another writers’ colony in Key West.

It was not long before Rolling Stone sent a photographer to take pictures of Tennessee. Her name was Annie Leibovitz. At that time, she had not done so much. We immediately got into an argument. She wanted to take Tennessee out and take pictures of him sitting in the back of a Rolls-Royce.

For some reason, I felt she was trying to take over my interview. She also told me she had heard that I had been in a popular bar, picking up women by telling them that I was interviewing Tennessee. There was some truth in that.

The next night I was perched up there at the bar with a sign saying “I’m interviewing Tennessee Williams.”

But the best part was the time of Capote. After shooting the breeze with Peter Fonda and director/writer Thomas McGuane, there to make the film 92 in the Shade, I would meet up with Capote for a late-night session of gossip, drinks, and barbecue. Capote had taken the art of gossip to its highest point.

The setting was perfect. Like the movie title, every day in Key West was 92 in the shade, with the evenings cooling off. There would be a select group of American expatriates gathered around Capote, who would be sipping his favorite cocktail and ripping into some good barbecue. I still remember a great story he told about Bianca Jagger falling in love with Jimi Hendrix at a dinner party); but he also had advice about how to write.

He told me three things you should never do when you write: “One, never use slang, it dates your work and you want to always make it classic; two, never take notes, and I forgot the third one, but I have it somewhere in my notes.”

I gathered that Williams and Capote were not on good terms with each other. They had once been the best of friends, but now they were on the outs. Capote’s relationship with Baldwin was in the same state.

Capote would ask me what I had been asking Tennessee that day. He would say things like “Ask him about Paco.” The next day, I asked Williams about “Paco.” He looked at me and said, “Who have you been talking to?”

One day when Williams and I went out for lunch, I told him about the advice that Capote had given me.

“Do you know,” he said, “ I do not believe that In Cold Blood is a good book. One night he told me that he did not believe that the people he wrote about were the actual people who committed the murder.” Williams looked over and said, “Isn’t that Capote over there?” And I looked and said, “No, that’s a lady and the big white hat.” “Yeah, but he wears hats like that!” Williams said.

Another time, I went to Williams’s house, and I saw that he was in the kitchen. But right before the kitchen, there was a table and at the table was sitting a Black woman, the maid, who asked me what it was that I was talking to Williams about. I told her we were discussing poets, like those who wrote “The Bridge,” and Rilke, the German poet.

She turned to Williams and told him to bring her a little more sugar for her coffee. Williams shuffled into the room with the sugar. I could not help but notice that he was serving her.

I mentioned it to Capote. He laughed and said to me. “Here’s an idea: you should write the whole interview from the point of that maid!”

It was not until I got back to Berkeley that I read a short story entitled, “A Day’s Work” in which Capote goes around with a Black cleaning woman, and interviews rich people on the east side of New York.

One evening, Capote had us all laughing about his encounter with James Baldwin.

“Jimmy told me that he was writing two novels,” Capote said but that he did want them to be “a protest novel,” or what he called, “a problem novel.”

Capote took a swig from his cocktail, and recalled the dialogue, “Jimmy, what is the plot of the novel that you’re having problems with?”

He said, “Well, the main novel is about a black homosexual being in love with a married Jewish woman!”

“I said, ‘My God, Jimmy, if that’s not a problem novel, I don’t know what the hell is!’”

The punchline sent us all sprawling into howling laughter.

He went on to say that his advice to Baldwin was not to write that novel but to concentrate on the manuscript that would become Go Tell It on the Mountain. Capote went on to say that after he read the manuscript, he, Capote, sent it to the publisher in New York who published it.

Which brings me back to the physical possibility of Baldwin being in New York during 1975-6, when Capote had his writer’s block and depression. When he was depressed around 1975, Baldwin arrived in New York, where he gave a talk at Saint John the Divine Cathedral.

Baldwin hated Nixon the way that we hate Donald Trump. In his speech, he called Nixon a “motherfucker.”

Gossip is a form of art that contains some truths, but it is also interactive in that each person must suss out the part that is true, and the part that is the vehicle of truth. The form itself is so orally tuned that it is easy to carry it without writing.

A little later in 1976, Baldwin showed up in Berkeley to visit me and we hung out and had a great time. Although he never mentioned Capote, I am willing to bet that if I had asked him he would have said, “Yeah, I stopped off to see if you were here to see to him on my way out of New York.” The fictional truth is a greater truth than any that we have in real life.

In 1982, I returned to Saint-Paul De Vence to visit Jimmy and was sitting with him and Bernard Hassell, an African-American expatriate, and the subject of Capote came up and I told the story he had told me about Baldwin’s “problem novel.” Jimmy laughed, but added that Capote had not given him advice and certainly had not helped him get the book published. He said it was “typical Truman!”

Gossip is a form of art that contains some truths, but it is also interactive in that each person must suss out the part that is true, and the part that is the vehicle of truth. The form itself is so orally tuned that it is easy to carry it without writing.

“I didn’t concern myself and I never would,” Mr. Chalk said in an interview this February in Town & Country magazine, “it’d be a train wreck to try. It would be too intimidating for me as an artist to go in and try to find the conversation and mimic it. So, whether it happened or not, my job was to make it feel fresh. In the time I had to prep, I just sucked up everything that I could that felt autobiographical and read a lot of Baldwin’s writing to get deeper into who he was so that I could honor it. That doesn’t really answer your question—did this really happen? I would never even care. I don’t want to bog myself down with that responsibility in that way.”

The artist has the responsibility of contributing to the welfare of society, Baldwin believed. When he saw Capote losing his self-esteem, he had to remind him of his obligation.

I have never seen a dramatic reenactment so true to the Baldwin I knew, and to the Capote I knew.