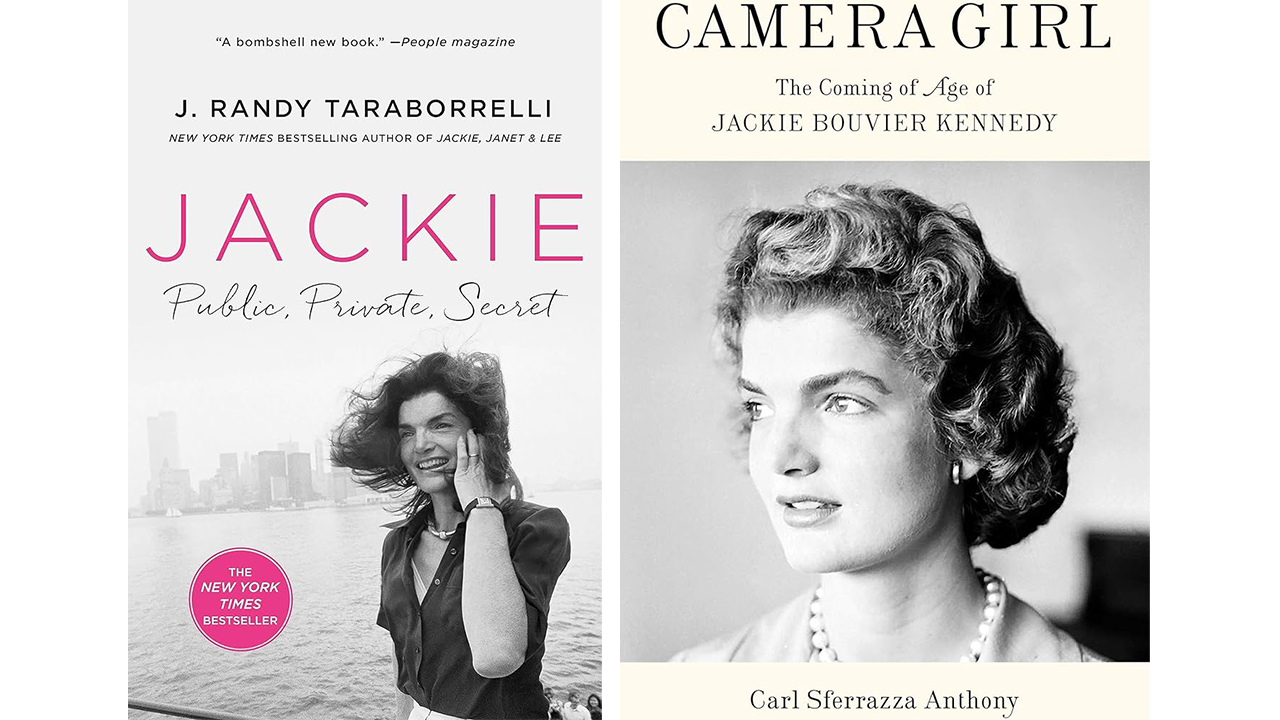

Jackie: Public, Private, Secret by J. Randy Taraborrelli ; St. Martin’s Press (2023) 501 pages with index, endnotes, and photos

Camera Girl: The Coming of Age of Jackie Bouvier Kennedy by Carl Sferrazza Anthony; Gallery Books (2023) 379 pages with index, endnotes, bibliography, and photos

Carl Sferrazza Anthony and J. Randy Taraborrelli are no strangers to the allure–and the perils–of documenting the lives of some of the most captivating and elusive figures of the twentieth century. Anthony’s previous books, As We Remember Her: Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis in the Words of Her Family and Friends and The Kennedy White House: Family Life and Pictures, 1961-1963, and Taraborrelli’s multiple Kennedy biographies, including Jackie, Ethel, Joan: Women of Camelot, and After Camelot: A Personal History of the Kennedy Family–1968 to the Present, position these biographers as contemporary authorities of the complicated personal and political lives of the Bouviers and Kennedys.

Writing a biography about Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, however, remains a daunting task, even thirty years after her death, not only because so many biographers have already attempted it, but also because this particular biographical subject spent significant time and resources resisting attempts to make her private life publicly available. In 1961, Jackie Kennedy tried to put a stop to a biography her mother had arranged with journalist Molly Thayer. In 1967, she filed a lawsuit to halt the publication of William Manchester’s book on JFK’s assassination. A decade later, she cut ties with her half-brother after his participation in Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized (and decidedly unforgiving) biography–a rift that remained irreparable to Jackie’s final days.

It is, perhaps, a testament to Jackie’s success as a resistant subject that these latest biographies–both meticulously researched and attuned to the complexity of Jackie’s political and personal contexts–arrive at such different versions of their central figure. Both Taraborrelli and Anthony reach for an authentic Jackie beneath the layers of scrupulously constructed self-representation populating the archives and historical record. In his preface, Taraborrelli laments that generations of fans, reporters, and the general public have long been “guilty of trying to make her something she was not and never wanted to be–not a mere mortal but, rather, some sort of mythological figure.” (xix) Taraborelli finds the authentic Jackie in her most “unguarded moments,” suggesting that we glimpse her humanity when Jackie’s carefully cultivated image momentarily falls away. He takes his subtitle from part of a conversation between Jackie and her friend and collaborator Jack Warnecke, who shared Jackie’s self-reflection: “I have three lives. Public, private, and secret.” (xix) For his part, Taraborrelli is clear that his biographical interests lie in the “secret” as he focuses on her early family dynamics and intimacies as a key to understanding her ambitions and relationships. Anthony, by contrast, locates the authentic Jackie in her early identity as a journalist and writer who sought independence from stifling familial influence and expectation and challenged the gender and class conventions of the time. Taken together, these latest biographical offerings provide even more complexity to an already-elusive woman who was simultaneously incredibly public and relentlessly private.

Writing a biography about Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis remains a daunting task, even thirty years after her death, not only because so many biographers have already attempted it, but also because this particular biographical subject spent significant time and resources resisting attempts to make her private life publicly available.

In the opening pages of his book, Taraborrelli writes that as Jackie was dying from cancer in 1994, she invited friends and loved ones, one at a time, to visit her Fifth Avenue apartment. As part of the occasion, she asked each of her visitors to help her review a selection of letters from a lifetime’s worth of written correspondence, before burning it, letter by letter, in the library fireplace. Jackie’s fierce commitment to protecting others’ privacy during her final days was matched only by a commitment to protect her own–and her children’s–privacy, even as she understood the very public and historical obligations of the life she lived as First Lady.

Indeed, from the early days of her relationship with Jack Kennedy, Jackie expertly navigated the unclear and evolving boundaries between public and private life, particularly as she and her ambitious husband moved in circles increasingly caught up in the spectacles of midcentury state and national politics. The relative privacy and class propriety that governed Jackie’s well-to-do upbringing–offering just enough publicity to secure a social reputation among the elite social circles–ran up against ongoing demands for disclosure and transparency after she married the up-and-coming Massachusetts junior senator and presidential contender. As Taraborrelli’s account reveals, Jackie herself well understood how to negotiate the gendered divisions between political publicity and familial privacy, consistently reinforcing a public image of Jack Kennedy as a devoted husband and father while simultaneously concealing the often-tumultuous realities of her private life. In addition to documenting the many ways that Jackie cultivated her many public and semi-public roles during and after the JFK years, Taraborrelli remains interested in the “secret” parts of Jackie’s imaginative and personal life that she stubbornly kept separate from either the public persona she could often (but not always) control and the private life that others tried to direct.

For Taraborrelli, the key to understanding the trajectory of Jackie’s life is her childhood as the daughter of a formidable mother determined to elevate her family’s social standing and secure a comfortable future for her two oldest daughters. Divorced from her daughters’ perpetually unfaithful father, Janet married Hugh Auchincloss, heir to the Standard Oil fortune, when Jackie was ten years old. The blended Auchincloss family–which included two of Hugh’s children from a previous marriage, Jackie and Lee Bouvier, and two younger children born to Janet and Hugh–gave Jackie privileged access to elite social networks, boarding school, excursions to Europe, and a private college education. Janet’s careful orchestration of Jackie’s social reputation (working especially to overcome the potential stigma of divorce and the family’s Catholicism within a largely WASP social elite) aimed above all at successful marriages for Jackie and Lee, who would have no inheritance of their own to rely upon when they came of age. “Mummy’s” intense control over every aspect of Jackie’s life–from clothing choices to her diet, social engagements, and choice of college–were non-negotiable and harshly enforced when necessary by a firm double slap across the face. When Jackie won a prestigious contest to become a junior editor at Vogue magazine,—a contest that Janet initially encouraged Jackie to enter–Janet forced her to quit after only a day on the job, presumably fearing that it would ruin Jackie’s marriage prospects and take Jackie permanently to Paris. Soon after Jackie became engaged (again, with her mother’s initial approval) to stockbroker John Husted, Janet forced Jackie to call it off after hearing about his financial debts. When Jackie’s seventeen-year-old sister Lee seemed to hit it off with a young Jack Kennedy at a Palm Beach party at the Kennedy compound, Janet demanded that Lee step aside so that Jackie could pursue him.

For Taraborrelli, the key to understanding the trajectory of Jackie’s life is her childhood as the daughter of a formidable mother determined to elevate her family’s social standing and secure a comfortable future for her two oldest daughters.

Taraborrelli’s account offers us a “secret” side of Jackie who, from her youth, actively seeks ways to flourish within considerable constraints imposed by her family and social expectations. This “secret” Jackie, quite different from the Jackie who remains impossibly dignified in the face of pain and crisis, is not only fallible but also experiences levels of suffering that remained hidden, even from those who thought they knew the “private” Jackie. Taraborrelli, for example, describes Jackie’s intense feelings of betrayal in response to Jack’s repeated infidelity–including multiple affairs with mutual acquaintances and more public figures like Marilyn Monroe–before and during the White House years as well as Jackie’s grief and abandonment after an early miscarriage and her subsequent delivery of a stillborn daughter while Jack was vacationing in Europe with friends. More than once, Taraborrelli reveals, Jackie contemplated divorce.

Taraborrelli also argues that growing up with a mother dedicated to upholding a flawless public image was important preparation for Jackie becoming part of the Kennedy family. Taraborrelli documents Jackie’s deep admiration for the Kennedys and a devotion to her in-laws that remained strong even decades after Jack’s murder, while also refusing to romanticize the stakes of belonging to such a powerful political family. Beyond the mutual affection between Jackie and the Kennedys, the match between Jackie and Jack was a savvy political choice that continued to pay off as Jack took national office–and her influential role was one that the Kennedys sought to preserve. As Jackie seriously considered divorce after the ordeal of the stillbirth (and speculated that a sexually transmitted infection she contracted from Jack had contributed to complications with the pregnancy), Jackie agreed to remain in the marriage after Joe Kennedy, Jack’s powerful father, offered her $100,000 for each living heir she would bring into the Kennedy family. Over time, Jackie found ways to live with her husband’s infidelities, just as Rose Kennedy, the family matriarch, had done with her own perpetually unfaithful husband. The death of Jack and Jackie’s son Patrick only four days after his premature birth in 1963 brought them closer in the months before Jack’s assassination. Taraborrelli makes clear that belonging to the Kennedys and sharing in the family’s political prowess came with emotional and personal costs.

In Taraborrelli’s telling, Jackie’s ability to navigate tremendous personal difficulties outside of the public eye, combined with her willingness to make concessions to maintain power and wealth, renders her both more flawed and more impressively human. But even as he seems to want to champion the headstrong and self-assured Jackie–the one who challenges her mother’s control, the propriety of sexual conventions, and the expectations of wifely self-sacrifice–Toraborrelli’s narrative imposes its own constraints on Jackie’s life story. With the exception of a brief preface describing Jackie’s final days, Jackie’s story takes shape largely in terms of the men in her life: the charismatic father (Jack Bouvier) she adores, the stepfather (Hugh Auchincloss) who provides her and her mother emotional and financial stability, and her two extraordinarily famous husbands. Where we might expect more of a chronological account of Jackie’s early years, the narrative proper begins with the immediate aftermath of JFK’s assassination–as if Jackie truly comes to life only through her husband’s fame and tragic death. As Taraborrelli moves back and forth in time throughout the first half of the book, we see Jackie hovering on the sidelines of national events like the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis–ready to perish with her husband and children on the front lawn of the White House rather than retreat to the underground bunker. She stands as an emotional, private resource for the president but not fully in touch with the political complexities of these critical moments. After Dallas, she becomes the “tragic heroine,” nobly witnessing the transfer of power and orchestrating Jack’s funeral as an event of national mourning. Her subsequent “rebirth” comes in the form of her relationship with Aristotle Onassis. To be sure, these events, especially JFK’s assassination, continued to shape Jackie’s choices, but Taraborrelli’s decision to frame Jackie’s life story as one dependent on a series of powerful men threatens to obscure Jackie’s considerable resistance to the powerful men who surrounded her and of her life separate from these relationships.

As Taraborrelli moves back and forth in time throughout the first half of the book, we see Jackie hovering on the sidelines of national events like the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis–ready to perish with her husband and children on the front lawn of the White House rather than retreat to the underground bunker.

Although Taraborrelli continues Jackie’s story well after Jack Kennedy’s death in 1963, his account is largely characterized by looking back to an inevitable comparison with the JFK years. Even in the decades following the assassination, Taraborrelli chronicles Jackie’s life as an escape from an image of the forever-grieving First Lady of the Kennedy years. Tarborelli also makes the case that Jackie’s attachment to a lifestyle that required enormous wealth–travels, fashion, art–led to her marriage to Aristotle Onassis, a partnership that Taraborrelli asserts was even more transactional and financially driven (on her part) than most people ever suspected. In his account, Jackie, like her mother before her, secured her own and her children’s futures in an agreement that guaranteed lifetime financial security, all without having to ever have sex with her second husband. Aristotle, for his part, continued his decades-long affair with opera singer Maria Callas as part of the agreement, content with having the famous Jacqueline Kennedy–now Jackie Onassis–as his bride. As Taraborrelli suggests, Jackie somehow managed to carve out a private existence and to maintain at least some secrets in yet another marriage that made her private life a source of ongoing and often intrusive public scrutiny.

Perhaps it is because Taraborrelli’s book gives us a powerful sense of Jackie’s ability to construct her persona for a wide variety of audiences, it is difficult to accept a version of Jackie who is anything but proactive, even if behind the scenes. Jackie’s letters to intimates, her family, her beloved Kennedys, politicians (including many to LBJ), and acquaintances from her travels illuminate her keen awareness of storytelling and strategic self-expression as much as her deep sense of loyalty and friendship. A reader gets the feeling that Jackie took special and practiced care never to reveal more than what she wanted others to see. Learning early in her teens that her father would only disburse allowances and gifts in exchange for her continued letters of affection to him, Jackie learned early on the value of consistent writing and performance of obligation. (In a world before email communication and social media, Jackie’s likely assumption that personal correspondence conferred a certain privacy helps to explain her powerful responses to hearing that her letters to family and friends had made their way into the hands of unauthorized biographers.) Rather than providing a straightforward glimpse into “the private world” of Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Jackie’s correspondence offers yet more layers of strategic self-presentation. Certainly, too, she understood the power of words and storytelling. Not only was she a voracious reader from a young age–finding solace in books rather than people after her parents’ divorce–but she learned early the value and purpose of family mythmaking. Her mother, Janet Lee Bouvier Auchincloss, repeatedly embellished a family tree that traced her lineage back to Lees of the American South rather than to Ireland. Janet’s enthusiasm to enlist Molly Thayer to pen the family biography stemmed in part from her determination to have everyone focus on Jackie and Jack and forget about Jackie’s previous fiancé in the process. Jackie herself tapped into the power of this familial mythmaking when, shortly after Jack’s assassination, she gave an interview with Life magazine. It was then that she reminisced about Jack’s love for the musical Camelot and attached it to his legacy–framing the nostalgic quasi-royal narrative of the Kennedys that America would also adopt for decades to come.

In Taraborrelli’s telling, Jackie’s ability to navigate tremendous personal difficulties outside of the public eye, combined with her willingness to make concessions to maintain power and wealth, renders her both more flawed and more impressively human. But even as he seems to want to champion the headstrong and self-assured Jackie–the one who challenges her mother’s control, the propriety of sexual conventions, and the expectations of wifely self-sacrifice–Toraborrelli’s narrative imposes its own constraints on Jackie’s life story.

Whereas Taraborrelli’s narrative seems to suggest that Jackie’s ambitions for money and power, combined with powerful familial and social forces, left her little say in a life defined by her politically savvy marriage and continuous adjustment to her husband’s political life, Anthony’s account positions Jackie as the unmistakable protagonist of her own life, her experiences and education laying the groundwork for choosing a life with Jack Kennedy characterized above all by shared ambition. This Jackie becomes a different kind of senator’s wife and a different kind of First Lady, reinventing the possibilities of an expected public image while cementing an unprecedented form of partnership behind the scenes. This biography also implicitly asks what JFK might have been like without Jackie–a question that Kennedy himself hinted at on a number of occasions.

In contrast with Taraborrelli’s version of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis, who stands as unique in spite of others’ relentless attempts to shape her image and direction, Anthony’s biography charts the story of a young woman who routinely challenges rigid expectations of gender and social class in pursuing her distinctly professional goals. While Taraborrelli’s narrative does not do justice to Jackie’s intellectual development and early career or, for that matter, help us understand why such a wealthy national figure would end her career as a book editor, Anthony offers us a portrait of a strong-willed, highly intellectual, and enterprising young woman most at home behind the camera, not in front of it.

Anthony highlights the clear intellect and creative vision of a young, driven Jacqueline Bouvier coming of age during a time when young women of her social class were not expected to graduate from college or have professional goals. Invited to list her ambition in her high school yearbook, she reported simply “Not to be a housewife,” defying the ideals her mother had already been scripting for her. (8) While Jackie certainly loved dancing, horseback riding, fashion, and the social life of New York City, she also immersed herself in her studies at Vassar, even petitioning to attend a study abroad program at the Sorbonne so that she could study art and become fluent in French. Jackie fell in love with Paris–and with her own independence–during her junior year abroad, even convincing her parents to extend her time in Europe well beyond the end of the semester. Although the facts remain unclear, it may have been Jackie’s willingness to break the rules (particularly a strict curfew) that led to her transfer to George Washington University (and to commuting from home) for her senior year–but she remained intent on graduating from college.

Jackie also stood out academically throughout her years at school, learning multiple languages, happily immersing herself in the classics, and contemplating a future in journalism. Anthony details the tremendous and sustained effort and range of insight that Jackie demonstrated in her multiple rounds of carefully researched and crafted submissions and in an assignment to reimagine an entire issue of the magazine. As Anthony describes it, her essay for the final round of the contest was “a small masterpiece” (120) that included an introductory editorial and outlines for six articles about fashion and five other feature articles that showcased her wide-ranging knowledge of contemporary fashion, literature, and culture. Anthony, like Taraborrelli, describes Janet’s harsh refusal to allow her daughter to assume the junior editor roles promised as the reward for winning the contest, including her worries that the job would take her back to Paris and away from marriage prospects at home. Unlike Taraborrelli, however, Anthony stresses just how crucial the Vogue win was for Jackie’s understanding of her own potential. She may have ultimately been thwarted in her goal to work at Vogue, but winning the contest enabled her to envision a future as a writer.

While Taraborrelli’s narrative does not do justice to Jackie’s intellectual development and early career or, for that matter, help us understand why such a wealthy national figure would end her career as a book editor, Anthony offers us a portrait of a strong-willed, highly intellectual, and enterprising young woman most at home behind the camera, not in front of it.

Not at all deterred from the idea of a job in journalism, Jackie used her family connections to secure a part-time job at the Washington Times-Herald after graduating from George Washington University and a summer with her sister in Europe. In these formative years (ones that Taraborrelli barely mentions), Jackie worked diligently to prove herself to her editor, Frank C. Waldrop. First taking on part-time clerical work, Jackie was soon assigned to ask everyday people on the street questions about current events and trends in support of a column called the “Inquiring Photographer.” The column eventually became hers, marking the first time the column was written by a woman, and the column itself was soon renamed “Inquiring Camera Girl.” Jackie learned how to use a Speed Graflex camera and built a following for her columns, which also often included her cartoon illustrations. Anthony emphasizes Jackie’s skillful ability to seek out and interview subjects from a wide range of backgrounds–from working-class people on the street to senators and movie actors–asking about issues that spanned current fashion trends to political events. Building on her past experiences traveling in Europe, Jackie cultivated an ability to talk with a diversity of people she would not otherwise have encountered in her social circles, a formative experience that would help her succeed in the world of politics in her life to come. Characteristically, too, Jackie sought to excel at the work, to turn an everyday column into something greater and more far-reaching. Aspiring to write feature articles for the paper, she put in long hours and met her deadlines for the six-day-a-week column, all the while carefully honing her craft. Her work eventually earned her not only a byline and two significant raises, but the respect of her colleagues.

In Anthony’s account, Jackie’s social life exists on the edges of her journalistic work. For her part, Jackie resisted the notion that she would have to choose between marriage and career, continuing in her role even after becoming engaged to John Husted, and her editor steered her toward further opportunities in the hope that Jackie would continue at the paper. While Taraborrelli’s biography depicts Jackie’s rejection of John Husted and her early courtship with Jack Kennedy as the outcome of an overbearing mother’s manipulations, Anthony mostly leaves Jackie’s mother out of the story, framing Jackie’s broken engagement to John Husted as an inevitable consequence of serious personal and intellectual incompatibility. Irritated by Jackie’s devotion to her work at the paper, Husted called her job “insipid,” clearly expecting her to give it up and move to New York. Jackie’s conversations with Jack Kennedy, on the other hand, were full of shared interests in global politics and culture. By all accounts, Jack quickly came to see Jackie as unique among the many women he dated for her intellectual curiosity and deep understanding of world events. Anthony dispels any temptation to see the newly available Jackie as patiently waiting for Jack Kennedy to notice her and to pull her into his political orbit. As Jack pursued his political ambition to unseat Henry Cabot Lodge as Massachusetts’ senator, Jackie was busy with her own plans as an aspiring writer, penning a children’s book and writing a television documentary script about nearby Octagon House, thought to be haunted by the ghost of First Lady Dolley Madison. As Anthony reveals, Jackie was conscientiously pursuing a career in writing, already looking to the next projects beyond her column work and seeking new opportunities to break into the field.

Anthony’s biography insists that we see Jackie Bouvier–intellectual, journalist, experienced world traveler–as someone who shaped Jack Kennedy’s narrative as much as he shaped hers, even if she could not always be seen doing so. Jackie’s deep knowledge of the history of French colonial rule in Vietnam and her fluent French made her a logical thought partner and translator as Jack developed his political speeches on Vietnam.

In his depiction of Jackie, Anthony offers us a portrait of a young professional seriously contemplating a future as a married journalist. Challenging the expectations of her editor and the culture at large, Jackie holds out hope for working in some capacity at the Times-Herald after marriage and is angered by a premature engagement announcement in the paper (presumably provided by the Kennedys) that reported her departure from her reporter job. As Anthony points out, Jackie’s angry disappointment signaled her attachment to her identity as an ambitious journalist unwillingly deprived of opportunity; this was not, as others would have it, the reaction of a newly engaged socialite happily absolved of professional responsibility.

Anthony’s biography insists that we see Jackie Bouvier–intellectual, journalist, experienced world traveler–as someone who shaped Jack Kennedy’s narrative as much as he shaped hers, even if she could not always be seen doing so. Jackie’s deep knowledge of the history of French colonial rule in Vietnam and her fluent French made her a logical thought partner and translator as Jack developed his political speeches on Vietnam. Jackie produced a report on the colonial and diplomatic history of French Indochina for Jack, translating key sources from the French. Culminating in an impressive eighty-four-page report that became a core source in Kennedy’s speech on the Senate Floor in 1953 advocating for an independent Vietnam, Jackie helped Jack secure his political reputation while also proving herself his intellectual equal. Anthony’s clear depiction of Jack and Jackie above all as “partners” offers a version of their marriage held together from the beginning by their personal, religious, and intellectual compatibility. Whereas Taraborrelli focuses on the painful moments of abandonment and betrayal that nearly end in divorce, Anthony showcases Jackie’s fortitude and clear-eyed awareness of her husband’s infidelities and other weaknesses, well known to her long before their engagement.

More than anything, however, Anthony’s biography offers a narrative of Jackie’s life before her marriage to Jack that quietly posits a counterfactual and equally plausible future for Jackie Bouvier as an accomplished writer and journalist. If a much older Jackie wistfully saw the unusual career of Gloria Emerson–the award-winning New York Times Vietnam war correspondent–as the path not taken, Anthony frames Jackie’s early years as setting up a biographical narrative that most certainly would have allowed for it.