Hindu Marriage: Divine, Dharmic, or Daring!

Or, how I learned to stop worrying and accept endogamy.

By Deepak Sarma

November 19, 2021

0. Married to my work

There are many reasons why I began to study Hinduism as an undergraduate at Reed College. One of them was to uncover reasons why I was supposed to have an arranged marriage, Hindu style, with the suitable bride, from the suitable background, with the suitable pedigree. My parents, who incidentally/ironically did not have an arranged marriage, would fantasize often when my brother and I were younger about orchestrating such an alliance for us.¹ Once I hit puberty and my “American” (i.e., White, Caucasian, non-Indian) friends began dating, I started questioning this arrangement that seemed to deny me my personal choices and the right to find a partner of my own. In college, I strategized that one way to gain control of my destiny, to deflect and deflate my parents’ desires to arrange my marriage, was to major in religious studies, go to graduate school, learn about Hinduism, and to become an expert.

1. Amar Chitra Katha (Immortal Illustrated Stories)

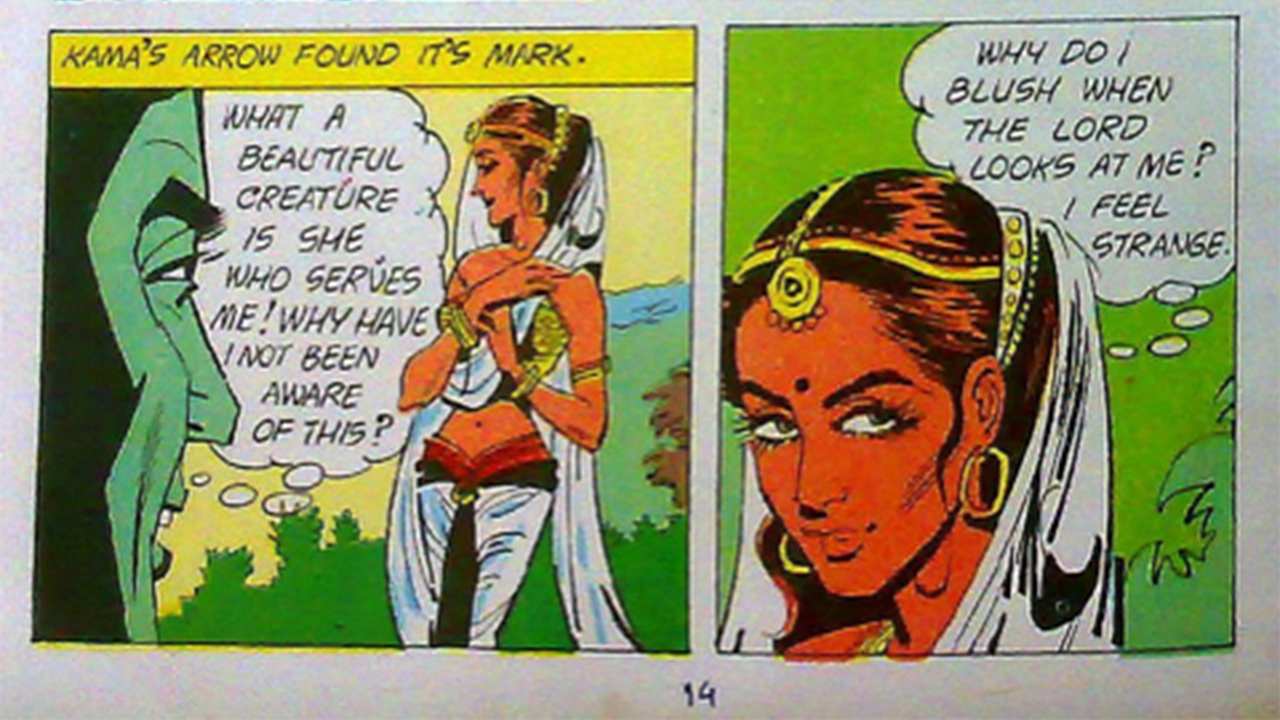

My confusion was not merely because of the tension I experienced as the child of first-generation Indian immigrants. It was also the product of being an avid reader of Amar Chitra Katha (Immortal Illustrated Stories) (hereafter ACK), a comic book series that was born in 1967 and was designed to inculcate/indoctrinate English-speaking Hindu children in India and in the diaspora about the stories and myths of Hinduism and India. These entertaining stories and myths were conglomerations of tales from several Hindu texts, including the Purāṇas, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata, and even plays written by the fifth-century dramatist Kālidāsa. The goddesses and gods, heroines and heroes portrayed were, in my eyes, aspirational models for my behavior, morals, and outlook. ACK provided, in the minds of many Hindu parents (who likely never read it) and in the mind of Anant Pai, the creator of the series, good, clean, and wholesome fun. Not to mention a way to pass on Hindu stories and mores to the younger generation, and especially those of us in the Hindu diaspora.

1.1 Goddesses or pin-ups?

But many well-intentioned and innocent parents did not consider what AKC could do to young and malleable minds. AKC was filled with gender stereotypes and representations, unvirtuous godly behavior, and presented the unjust hierarchy of the class and caste system as if it were acceptable. The goddesses and female characters, for example, were portrayed as hyper-sexualized. They were scantily clad, drawn with big breasts and tiny waists, had wide hips, and wore lots of jewelry. They looked nothing like the south Indian girls that I had seen at Carnatic Music concerts and at the Śri Mahā Vallabha Ganapati Devasthānam in Flushing New York² who usually wore a pavada (a traditional dress worn mainly by young girls comprising a “tunic” and skirt that hangs from the waist down to the toes), or the south Indian mothers (the “aunties”) who wore the traditional Indian sari (ignoring the midriff exposure) or the “modern”: salwar kameez, which was—gasp!—a north Indian style.

These AKC voluptuous vixens had sex out of wedlock with whichever bulging biceped God/hero saved them from whatever predicament they were in. (Their sexual congress, of course, was implied and never depicted in the AKC comics). And their marriages, moreover, which sometimes took place after their suggested liaison, were certainly not arranged!

Young impressionable reader that I was, I wondered if I was going to marry a woman who looked (or behaved) like one of these goddesses? If so, then why would my marriage need to be arranged?

1.2 Divine Darśan (vision): Epic love at first sight

In some cases, such as the affair between King Duṣyanta and Śakuntalā, told by Kālidāsa in his play Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā), and retold of course in my favorite Amar Chitra Katha comic, Duṣyanta, the hero/protagonist, falls in love with Śakuntalā merely after seeing her.³ Stunned, he says, “What? This is the daughter of Kanva? How amazing!”⁴ And then seeing her partly disrobed (her clothes are caught in some foliage), he describes her:

Lower lip has the hue of a sprouting tendril,

her arms imitate tender branches.

Youth, desirable like a flower, is primed

in her physique.⁵

And then, just before she is tormented by a bee and is saved by the valiant and chivalrous Duṣyanta, he thinks to himself:

Doubtless she is fit to be wed by a warrior,

since my heart desires her so.⁶

If King Duṣyanta could fall in love at first sight, then surely I could. And to make matters even more romantic, similar feelings are evoked in a passionate Śakuntalā. She thinks to herself:

What is this? No sooner have I seen him than I have become susceptible to feelings out of place in this penance grove.⁷

Having read, and reread, the corresponding pages in the AKC comic books version,⁸ I innocently developed an adolescent crush on Śakuntalā and dreamed of marrying her one day. The Buffoon in Kalidāsa’s play worries about Duṣyanta: “He’s suffering another bout of the “Śakuntalā”-disease. I don’t know how he can be cured.”⁹ How could I be cured of this pre-pubescent pining?

In other cases, the family of the bride-to-be arranges a svayaṁvara (literally “self-choice”), a contest where suitors display extraordinary (and often divine) feats of strength in order to “win the hand of the bride.” In the Rāmāyaṇa, for example, the god Rāma successfully lifts and breaks Pināka, the bow of Śiva, and thus proves himself worthy to be the husband of the goddess Sītā and is awarded her hand in marriage.¹⁰ Rāma and Sītā are described by R. K. Narayana in his retelling as having seen each other before the competition and, like Duṣyanta and Śakuntalā, felt instant attraction for one another:¹¹

. . . Now Rama observed on a balcony princess Sita playing with her companions. He stood arrested by her beauty, and she noticed him at the same moment. Their eyes met. They had been together not so long ago in Vaikunta, their original home in heaven, as Vishnu and his spouse Lakshmi, but in their present incarnation, suffering all the limitations of mortals, they looked at each other as strangers. Sita, decked in ornaments and flowers, in the midst of her attendants, flashed on his eyes like a streak of lightning. She paused to watch Rama slowly pass out of view, along with his sage-master and brother. The moment he vanished, her mind became uncontrollably agitated. The eye had admitted a slender shaft of love, which later expanded and spread into her whole being.¹²

And in R. K. Narayanan’s mind things did not fare better for Rāma:

At the guest house, Rama retired for the night. In the seclusion of his bedroom, he began to brood over the girl he had noticed on the palace balcony. For him, too, the moon seemed to emphasize his sense of loneliness. Although he had exhibited no sign of it, deeply within he felt a disturbance. His innate sense of discipline and propriety had made him conceal his feelings before other people. Now he kept thinking of the girl on the balcony and longed for another sight of her.¹³

Were Rāma and Duṣyanta also pierced by the arrow of Kāma (the god of love)? Would I succumb in a similar way? How could I make myself a target of the god Kāma? This sort of romance seemed nothing like the arrangement proposed by my parents, where love came after, not before, marriage.

In the epic, the Mahābhārata Arjuna wins the hand of Draupadī, by shooting five arrows through a hole in a wheel (according to the account in the AKC, the task was even more challenging: the suitor should penetrate the eye of a fish placed up high on a revolving pole while looking only at its reflection in a nearby pool of water!).¹⁴ While this seems somewhat reasonable, in an epic hero sort of way, it is made much more complicated by Kuntī, his mother. He reports to her that he has brought home some “alms” and, before knowing what (or who) it was, she tells him that he needs to share it with his four brothers!:

[They spoke] . . . of Draupadi, “Look what we found!”

She was inside the house without seeing her sons

And she merely said, “Now you share that together!”

Later on did Kunti set eyes on the girl

And cried out, “Woe! O what have I said!”¹⁵

Draupadī thus becomes the most well-known polyandrous wife in Hindu mythology, with five husbands to boot.

What was a young ABCD “(American Born Confused Desi)” to do with these narratives? Was getting a degree in engineering or gaining admission to medical school akin to Arjuna’s feat of strength, albeit intellectually/academically manifested? Or did I need to train in a gym for the equivalent of American Ninja Warrior? And the fundamental dilemmas remained: How was I to fulfill the desires of my beloved parents to have an arranged marriage and, at the same time, fulfill my own desires? How did one find a suitable and compatible partner?

What was a young ABCD “(American Born Confused Desi)” to do with these narratives? Was getting a degree in engineering or gaining admission to medical school akin to Arjuna’s feat of strength, albeit intellectually/academically manifested?

2. Paradoxes and paradigms

On the one hand, Hindus have placed tremendous importance on arranging the marriages of their children and relatives. On the other hand, there is an important (and impossible to ignore) history of pre-marital sex, love marriages, and even polyamorous relationships among the goddesses and gods in texts held sacred by the same Hindus. Which one is endorsed (and who endorses it)? The erotic model or the ascetic one?¹⁶ The one in which a young man should welcome romance, or the model in which a young man should avoiding talking with women and be celibate? How are they to be understood in the time of Netflix’s immensely popular Indian Matchmaking, a cringeworthy docuseries about a zealous matchmaker in India?

3. Divine, Dharmic, Dharma-derived, and daring marriages

I will stipulate that there are four types of Hindu marriages: Divine, Dharmic, Dharma-derived, and Daring. Divine marriages are depicted in the Hindu myths and epics (and in Bollywood films). Dharmic ones are models prescribed or described in the dharma-śāstras (treatises on proper—and improper!—behavior). Dharma-derived marriages are those followed by contemporary practicing Hindus who seek to uphold the caste and class system. Daring marriages, which are the most unconventional, are for those families and couples who merely seek to ensure spousal compatibility, independent of caste or class concerns.

It is obviously not the case that examples found in actual Hindu marriages are necessarily going to fit perfectly in any one of these four categories. Take the case of my parents, for instance, where my father had a love marriage, and my mother had an arranged one. Their marriage is a hybrid and stands between Dharma-derived and Daring. Hence, these various groupings are best understood as ideal types and as useful heuristic devices.

3.1 Divine marriages: marriages made in heaven

The styles and kinds of marriages in the Hindu myths and epics (such as those depicted in the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata mentioned previously) do not fit the pattern embraced by most contemporary Hindus. These unions are regarded by more secular-minded Hindus as mere fantasy or matters of imagination. And for those who are more religiously minded, the gods and goddesses are given a divine carte blanche, a blessed loophole to follow an entirely different set of rules. After all, gods and goddesses flirt in mysterious ways!

Bollywood heroes and heroines, like their divine counterparts, very rarely follow the prevailing practices concerning arranged marriage. Instead, the plots often involve heroes and heroines abandoning arranged marriages just as the bride (or groom) is sashaying towards the wedding mandap (wedding altar) and running off with their true love for a romantic song and dance sequence on some picturesque Swiss or Kashmiri mountain.

Some believe that since the gods and goddesses are members of the kṣatriya class, the rules that they followed were appropriate and different from Brahminical ones. This, of course, is a variant of the divine loophole but placed in the caste context. In this interpretation, Brahmins may maintain the protocols of the dharma-śāstras (treatises on proper behavior) and excuse the kṣatriya gods and goddesses for their permissible transgressions.

Incidentally, the stories told in Bollywood films resemble those found in the Purāṇas, the Rāmāyaṇa, and Mahābhārata. Bollywood heroes and heroines, like their divine counterparts, very rarely follow the prevailing practices concerning arranged marriage. Instead, the plots often involve heroes and heroines abandoning arranged marriages just as the bride (or groom) is sashaying towards the wedding mandap (wedding altar) and running off with their true love for a romantic song and dance sequence on some picturesque Swiss or Kashmiri mountain. The modern gods and goddesses of the silver screen are given cinematic autonomy, a celluloid escape clause, not unlike the gods and goddesses that they often imitate. I wonder if these serve to create the same sort of confusion for younger Desis that I felt when I read the Amar Chitra Katha comic books growing up in the ’70s.

3.2 dharma-śāstras (Treatises on Proper Behavior): Varṇa (class), Jāti (caste) and śuddha (purity)

Arranged marriage is a paradigmatic example of endogamy, the practice of marrying within a specific community. Though endogamy is practiced throughout the world, and, yes, even in the United States, it has been codified and instituted to the highest degree in Hinduism and in India in the context of varṇa (class) and jāti (caste) (a subset of varṇa). There are four varṇas, namely the brahmins (priestly class), kṣatriyas (the ruling class), vaiśyas (the merchant class), and the śūdras (the laboring class).¹⁷ Each of these were further subdivided into jātis. References to this social ordering are plentiful in most Hindu texts. It is central, however, to the prescriptions and prohibitions found in the dharma–śāstras. Among these, the most infamous is the Mānavadharmaśāstra (The Law Code of Manu). In the text, one finds the hierarchically arranged social world to be governed by śuddha (purity). Purity issues were preeminently embodied in the varṇa and jāti system as well as in gender protocols. They were manifested in terms of permissible and forbidden exchanges.¹⁸

The Brahmins were regarded to be the purest and were at the top of this society. In fact, some Brahmins were believed to be so pure that they purified those that they sat beside. According to the Mānavadharmaśāstra:

[On the topic of] Brahmins who purify a row of eaters defiled by someone alongside whom it is unfit to eat –listen to a complete enumeration of such Brahmins, who purify those alongside whom they eat. Men of pre-eminence in all the Vedas in all the expository texts, as also descendants in a line of vedic scholars, should be regarded as persons who purify those alongside whom they eat . . . ¹⁹

Though by nature pure, Brahmins still had to follow practices that ensured, maintained, and enhanced their purity. In the dharma–śāstras one finds lists of activities that incurred aśuddha (impurity). These activities largely centered on transactions between members of different varṇas and jātis, between members of the same jāti, and even with oneself (bodily fluids). Arranged marriage (and endogamy) is prescribed in this text as it is essential to maintaining and perpetuating śuddha (purity).

3.2.1 Endogamy and eight types of marriage

Chapter Three of Manu concerns the selection of a bride after a young man has completed his religious education and states the quintessential prescription for endogamy in Hinduism. This is undeniably a precursor of the modern Hindu arranged marriage. Manu states:

. . . the twice-born should marry a wife belonging to the same class and possessing the right bodily characteristics. A girl who belongs to an ancestry different from his mother’s and to a lineage different from his father’s, and who is unrelated to him by marriage, is recommended for a twice-born man.²⁰

This must have been the basis for my parents’ insistence that I have a dharma-derived, arranged marriage. Manu next adds some guidance regarding polygamy and hypogamy (marrying someone of a lower varṇa or jāti):

At the first marriage, a woman of equal class is recommended for the twice-born men; but for those who proceed further through lust, there are, in order, the preferable women. A Śūdra may take only a Śūdra woman as a wife, a Vaiśya, the latter and a woman of his own class, a Kṣatriya, the latter two and a woman of his own class; and a Brahmin, the latter three and a woman of his own class.²¹

But then he offers this prohibition, which suggests that, for some, hypogamy is possible but not preferable:

Not a single story mentions a Brahmin or a Kṣatriya taking a Śūdra wife even when they were going through a time of adversity. When twice-born men foolishly marry low-caste wives, they quickly reduce even their families and children to the rank of Śūdras.²²

Setting the discrimination and social injustice aside, difficult as it may be, the text is clearly endorsing endogamy, which is foundational for those contemporary Hindus who are proponents of Dharma-derived arranged marriages.

Immediately following this section is one that outlines eight types of marriage, which are permissible for some varṇas but not others. This section is descriptive and not prescriptive and addresses marriages and unions that are not always arranged and some which have already occurred. These are “the Brahma, the Divine, the Seer’s, the Prājāpatya, the Demonic, the Gāndharva, the Fiendish, and the Ghoulish, which is the eighth and the worst.”²³ These are explained in detail:

When a man dresses a girl up, honors her, invites on his own a man of learning and virtue, and gives her to him, it is said to be the “Brahma” Law. When a man, while a sacrifice is being carried out properly, adorns his daughter and gives her to the officiating priest as he is performing the rite, it is called the “Divine” Law. When a man accepts a bull and a cow, or two pairs of them, from the bridegroom in accordance with the Law and gives a girl to him according to rule, it is called the “Seer’s” Law. When a man honors the girl and gives her after exhorting them with the words: “May you jointly fulfill the Law,” tradition calls it the “Prājāpatya” procedure. When a girl is given after the payment of money to the girl’s relatives and to the girl herself according to the man’s ability and out of his own free will, it is called the “Demonic” Law. When the girl and the groom have sex with each other voluntarily, that is the “Gāndharva” marriage based on sexual union and originating from love. When someone violently abducts a girl from her house as she is shrieking and weeping by causing death, mayhem, and destruction, it is called the “Fiendish” procedure. When someone secretly rapes a woman who is asleep, drunk, or mentally deranged, it is the eighth known as “Ghoulish,” the most evil of marriages.²⁴

The belief that the rules that gods and goddesses followed were appropriate and different since they were Kṣatriyas is confirmed in two types of marriages: “the Gāndharva and the Fiendish, whether undertaken separately or conjointly, are viewed by tradition as lawful for Kṣatriyas.”²⁵ Marriages that are products of conventional “American” dating culture would be characterized as Gāndharva marriages in this view, and, in this context, are the most daring.

One may incorrectly think that varṇa and jāti are no longer relevant in today’s secular India. It is undeniable that Articles 15 and 17 of the Indian Constitution prohibit class and caste discrimination:

15. Prohibition of discrimination of grounds of religion, race caste, sex, and birth.

17. Abolition of Untouchability –“Untouchability: is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of “Untouchability” shall be an offense punishable in accordance with law.²⁶

That these Articles now exist does not mean these socio-religious structures were not a part of the history of “Hinduism.” The abolition of varṇa and jāti by these Articles, moreover, do not mean that they have been abolished in practice. Indeed, varṇa and jāti are very much alive today in India and still play a significant role in Hindu arranged marriages and are the core of the dharma-derived ones.

3.3 What about dowry? The price of a Hindu marriage

Many still demand dowries, where the groom’s family stipulates that the bride’s family pay them money and/or property at the time of marriage. Ironically this is the opposite of the practice of purchasing a wife, which is forbidden in Manu. Manu proclaims:

A learned father must never accept even the slightest bride-price for his daughter; for by greedily accepting a bride-price, a man becomes a trafficker in his offspring. When relatives foolishly live off a woman’s wealth—slave women, vehicles, or clothes—those evil men will descend along the downward course.²⁷

The only references to a practice akin to today’s practice of dowry are found in the “Divine Law” and “Seer’s Marriage”:

When a man, while a sacrifice is being carried out properly, adorns his daughter and gives her to the officiating priest as he is performing the rite, it is called the “Divine” Law. . . . When a man accepts a bull and a cow, or two pairs of them, from the bridegroom in accordance with the Law and gives a girl to him according to rule, it is called the “Seer’s” Law.”²⁸

While this is illegal in India²⁹ and standard practice in Hindu arranged marriages, it is not prescribed in Manu.

3.4 Never Gonna Fall For (Modern Love)

As the popularity of Netflix’s Indian Matchmaking and Amazon’s Arranged prove, arranged (or semi-arranged) marriages are still a very important part of Hinduism, both inside and outside of the Indian subcontinent. In every Hindu community, there are matchmakers who are adept at finding suitable alliances for willing parties. My parents, like so many others, have played a part in successful alliances for others or have been instrumental in arranging dates and eventually marriages.

One would think that “millennial” and “generation Z” Hindus have relegated the practice of arranged marriage to the dustbin of history.³⁰ But this is not the case. In this connection, I was fortunate to speak to undergraduate students of Indian heritage recently about issues concerning social justice and related topics. They almost unanimously said that they were dating (or would date) people across (humanly constructed) “ethnic,” “racial,” and “religious” lines, and this included varṇa and jāti. But when I pushed them on this and asked if they had told their parents about who they were dating, the vast majority reported that they had not let their parents know that they were dating in the first place. They balked when asked if they were comfortable bringing their significant others home to meet their parents if their partner was not “suitable” (i.e., incompatible) and if the union would be one that was not endogamous (and did not follow Manu’s prescriptions). Finally, and most telling, when I asked them if they would marry their partner, if their partner was not born into the appropriate varṇa and jāti, and they said “no.”

Alas.

Despite being somewhat romantically experimental at college, many, if not most, students were followers of the dharma-derived marriage plan. They anticipated having either an arranged marriage, or semi-arranged marriage, with a partner who fit their parents’ class and caste requirements and was properly vetted. When pushed, they repeated the party line–that they wanted to meet someone who had a similar background, similar dietary restrictions, spoke a similar language, and practiced similar rituals and customs. This last desideratum, to share customs and practices, is a coded way of stipulating that potential partners would have to share the same varṇa and likely the same jāti, and therefore reveals an endorsement of arranged marriage. Hindu arranged marriages of the dharma-derived variety are alive and well, even among the “millennials” and “generation Zs” who are not quite so daring as even the unconventional Hindu gods and goddesses!

One would think that “millennial” and “generation Z” Hindus have relegated the practice of arranged marriage to the dustbin of history. But this is not the case.

But surely this desire for similarity, characterized in the corporate world as similarity bias, is not really that unusual. While it is true that Hindu marriage involves arrangements according to very specific criteria, many marriages in non-Hindu worlds in North America involve endogamy. Non-Hindus often seek partners who have similar backgrounds: ethnic, religious, and sometimes even economic. These criteria may not be as overt as they are in the Hindu context, but it is hard to deny that these criteria exist (a quick look at the search categories on match.com will dispel any notion that arranged dating/marriage is not prevalent outside of Hinduism). Take, for example, Bridgerton, Netflix’s enormously popular serial about arranged dating among European aristocracy. People from the same social class and religious community often arrange dates between members. People from ethnic communities also do the same. And people are often encouraged to date others with similar backgrounds and are discouraged from dating outside of the approved pool. Sometimes these exhortations are simple threats: I briefly dated an African American woman in graduate school who warned me that I was the first person that she was involved with that was “outside of her race” (her language) and that if her brothers found out they would “beat me to a bloody mess.” That relationship, not surprisingly, was short-lived. My first marriage, which ended in divorce, was with a White-Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) woman whose White-liberal-racist parents, on countless occasions, expressed their disappointment that I was not also a WASP. While they may not have sought an arranged marriage for their daughter, like Matthew Drayton in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, they certainly did not embrace (and certainly sought to sabotage!) our cross-cultural, cross-religious, cross-racial combination. Their threat was much more subtle and insidious than the threat of violence and much more damaging too.

4. To arrange or not to arrange? That is the question!

The time immediately following my divorce was tumultuous and existentially disruptive, if not transformative. I wondered if I should I have followed the tried-and-true path of an arranged Hindu marriage? If I should have listened to Manu and sought “a wife belonging to the same class”? I wondered if, moving forward, I should embrace a dharma-derivative alliance (no more daring dalliances!)? Most critically, I wondered if I should ask my parents to screen any potential matches.

With my self-confidence at an all-time low, I decided that I would ask my parents to assess my choices and gave them veto power. They were not confident about finding a suitable alliance for me as I was disadvantaged thrice over—i.e., I was not a “good catch.” Not only was I damaged goods (I had a life-changing head injury while I was in graduate school³¹), and not only was I a mere impecunious faculty member in a humanities department (and not a medical doctor, an engineer, or an IT savant), but I was a doomed divorcee.

I also worried that participating in the Hindu marriage system meant upholding and maintaining the humanly constructed injustices of the varṇa and jāti system. I decided then, to be daring and to embrace a “semi-arranged” marriage paradigm, where I might meet someone on my own, via an Indian oriented internet dating site such as shaadi.com or by any of the myriad ways of meeting potential partners, and, if things progressed, I would have my parents vet them. If they passed through this process unscathed then, and only then, might I consider taking things to the next level. But would a potential and compatible partner find involving parents so early to be acceptable?

5. Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā)!

A few months after making the momentous decision to include my parents, I met someone. “What?” “How amazing!” Her name was Śakuntalā, and she was a woman of Indian heritage, who was a Marwari Jain, and not a Hindu. Śakuntalā was about my age and had a similar way of thinking. Being a Jain, she was also a member of a religion that repudiated the varṇa system and this harmonized with my own ideas about social justice. I gave her my business card and on the back of it she took notes about my background–my degrees, my employment, my dietary restrictions (though next to “divorced” she did have a question mark!). I did the same. We decided to meet again, having each passed this preliminary vetting process. On our first official date, she explained that she would only move forward with our relationship if I spoke to her parents, have my “bio-data” reviewed, and was properly screened! I was pleasantly surprised and told her that this was my precondition as well.³²

I decided to be proactive and totally transparent and provided for her my bank statements, my credit card invoices, my divorce papers, and even my medical records! I had nothing to hide and did not want there to be any significant or deal-breaking surprises. She inspected the materials with a fine-tooth comb, and I, thankfully, passed.

We both made calls to each other’s parents. Śakuntalā’s father posed some difficult questions to ascertain my worthiness, health, and sincerity. Two that stand out were “Do you still have all of your hair?” and “Do you still have all of your teeth?” (Affirmative on both!) My parents did not have quite as many questions and, in fact, endorsed the alliance wholeheartedly when they learned that she was a medical doctor! We had both successfully jumped through these preliminary hoops. We began dating with the objective of continuing the vetting process and, if all proceeded as planned, marrying.

It was rather uncomfortable to be interrogated by someone who was, at that time, a dozen years younger than me but I endured it, knowing that it was an integral component in the vetting process entailed by and expected of arranged marriages.

We arranged a number of trips to visit one another’s parents and siblings and to have in-person interviews. These all had favorable outcomes, even if they were somewhat arduous, as we had expected. Everything was on track. After six months of dating, we began to accept the real possibility of getting married. We had followed all the prescribed protocols and, barring some unforeseen obstacle, marriage was inevitable.

But the vicious vetting was not entirely over–for me, at least. I took a research trip to India and when I was there, I was to meet Śakuntalā’s young 22-year-old nephew, whose aim was to scrutinize me and my purportedly sordid past to satisfy my wife’s entire (and orthodox) Jain Marwari clan (a very large one indeed). Scrutinize me he did! It was rather uncomfortable to be interrogated by someone who was, at that time, a dozen years younger than me but I endured it, knowing that it was an integral component in the vetting process entailed by and expected of arranged marriages.

One month after I returned, and eleven months after we first met, Śakuntalā and I eloped and were married. That was sixteen years ago. It was indeed rather daring!³³

6. Hindu marriages: “Happily, Ever After” or “Happily, Never After”?

The process and structure of the Hindu arranged marriage is intriguing for both Hindus and non-Hindus. Most unmarried Hindus either will agree to have an arranged (or semi-arranged) marriage or are vehemently against it. Non-Hindus are usually confused and concerned by the lack of individual choice, wanting to locate all their marital stories in a romantic narrative that accentuates concurrently agency and serendipity, even if there is an element of arrangement (or semi- arrangement): parents, blind dates, religious communities, and so on. The Hindu marriage, at least the dharma-derived sort, is based on endogamy and the corresponding codified varṇa and jāti system, which many (non-Hindus and Hindus) find offensive, despite the class and racial hierarchies that are concealed and otherwise lurking in their worlds and that are important components for their marriages, social interactions, employment practices and so on.

Will Hindu arranged marriages become old-fashioned? Or eliminated, as Ambedkar had hoped, along with the caste and class system he so despised?³⁴ Given the popularity of the Netflix series Indian Matchmaking and the voiced reluctance of “millennial” and “generation Z” Hindus, it does not seem that it will lose favor any time soon. But even if the Hindu version of endogamy was to fade away, that does not mean that the more generic one that was glorified in Bridgerton will vanish either.

Are romantic songs such as Goose’s “Honey Bee” merely subliminal recommendations for listeners to seek an arranged marriage?

She’s my honey bee

Someone just like me . . .

. . . She’s my honey bee

Flying just like me. ³⁵

1 My father would agree that he did not have an arranged marriage. My mother, however, regards it as arranged.

2 https://nyganeshtemple.org

3 Kalidāsa, Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā), Scene 1

4 Kalidāsa, Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā), 1.73. All translations from Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā), are taken from Somadeva Vasudeva’s wonderful translation as published in the Clay Sanskrit Library’s Abhijñānaśakuntalā (The Recognition of Śakuntalā) (NYU Press, 2006).

5 Kalidāsa 1.90.

6 Kalidāsa 1.96.

7 Kalidāsa 1.120.

8 Pai, Ananta. Shakuntala. Amar Chitra Katha No. 12, Mumbai: India Book House, 1970).

9 Kalidāsa 6.83.

10 Rāmāyaṇa. Sarga 66, Bālakāṇḍa. See also Rama. Amar Chitra Katha No. 15, Mumbai: India Book House, 1970).

11 Narayan, R. K,. The Ramayana (London: Penguin, 1972), 24.

14 Vyāsa, The Mahābhārata, 1.12.178-180. Translated by J. A. B. van Buitenen. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980).

15 MBh, 1.12.182.1 See also The Pandava Princes. Amar Chitra Katha No. 13, (Mumbai: India Book House, 1970).

16 I am dependent here on Doniger’s insight on this tension as found in her Śiva; The Erotic Ascetic. Doniger, Wendy. Śiva; The Erotic Ascetic. (NY: Oxford University Press, 1973).

17 My reference to the varṇa (class) and jāti (caste) system here and throughout this paper does not mean that I support or even condone this discriminative and socially unjust system.

18 See L. Dumont, Home Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); T. N. Madan, “Concerning the Categories shuddha and ashuddha in Hindu Culture: an Exploratory Essay”, in J. Carman and F. Marglin, eds., Purity and Auspiciousness in Indian Society (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1985): 11-29; M. N. Srinivas, “Varna and Caste” in M. N. Srinivas, ed., Collected Essays (Oxford: Delhi, 2002): 166-172; M. Marriott, “Hindu Transactions: Diversity Without Dualism” in B. Kapferer, ed., Transaction and Meaning: Directions in the Anthropology of Exchange and Symbolic Behavior (Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1976): 109-142.

19 P. Olivelle, translator, The Law Code of Manu (NY: Oxford University Press, 2004): chapter 3, verse 183-3,185 at 57. All passages from Mānavadharmaśāstra are taken from this lucid translation. Hereafter MDS

20 MDS 3.4-3.5

26 https://www.constitutionofindia.net/constitution_of_india/fundamental_rights/articles/Article%2015

28 MDS 5.29-30

29 See The Dowry Prevention Act of 1961, https://wcd.nic.in/act/dowry-prohibition-act-1961

30 I am relying on the categories as defined by the PEW Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/

31 https://soundcloud.com/moca-cleveland/deepak-sarma-on-the-death-of

32 See Lee, Ji Hyun, “Modern Lessons from Arranged Marriages.” NY Times, 2013-01-20. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/20/fashion/weddings/parental-involvement-can-help-in-choosing-marriage-partners-experts-say.html

33 It was daring for me. Śakuntalā might say that it had more dharma-derivative elements than daring ones. So the marriage is mixed on many levels.

34 See B. Ambedkar. “The Annihilation of Caste” 1936. Ambedkar hoped that inter-caste marriage and dining would result in the death of the class and caste system.

35 “Honey Bee” by Goose. Debuted Dec. 21, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pO40zjmaxXo