Good Morning, Belarus

A Washington University screenwriting lecturer recalls a trip twenty years ago to Belarus that was not only “stranger than fiction” but “stranger than strange.”

March 25, 2022

The breakfast menu of Minsk’s “5-Star” Hotel Planeta boasted a beet omelet that under the fluorescent lighting appeared to be a fluffy concoction of powdered eggs and a mass of purplish cabbage. Good Morning, Belarus… a grim totalitarian wedge carved out of Cold War Soviet Union, Poland, and maybe a sliver of Romania?

“So you’re off to the bad place today?” Looming over me was Dr. Bill Novick, the pediatric cardiac surgeon from Memphis whom I had already cast as Brad Pitt for the movie I was researching for HBO in the fall of 2002. Brad did not know about any of this yet but how could he resist playing the former Alabama football star, now the quarterback of a crack surgical team funded by the Chernobyl Children’s Foundation, co-founded by Bono’s wife Allie Hewson and her cadre of radical humanitarian Irishwomen? This was going to be a strange trip, indeed, but for a somewhat cynical screenwriter it might turn into “Oscar Gold”—that rare alchemy that transforms a compelling true story into movie magic. I would soon find out that in Belarus truth is not only stranger than fiction, it is stranger than strange.

The heart is one of the organs most vulnerable to the effects of radiation and thousands of children in Ukraine and Belarus are born with genetic heart diseases and defects.

Bill comes to Belarus every year with the Flying Doctors Cardiac Mission. He assembles an international crew of volunteer surgical nurses, an anesthesiologist, and a perfusionist to perform seventy-five open-heart surgeries on children ranging in age from six months to sixteen years. Operating on a heart the size of a walnut requires amazing dexterity and looking at Dr. Bill’s giant mitts it was hard to believe he had become one of the world’s top pediatric “chest cutters.” He is also the last hope for these kids who suffer from “Chernobyl Heart,” a congenital heart disease whose roots go back to radiation fallout from the nuclear reactor meltdown. The heart is one of the organs most vulnerable to the effects of radiation and thousands of children in Ukraine and Belarus are born with genetic heart diseases and defects.

Fetal alcohol syndrome inherited from their birth mothers was yet another death card they are dealt. Tomorrow I would watch Dr. Novick trying to shuffle the deck and help these doomed youngsters cheat the Reaper. But today I was on my way to the Gomel region, also known as “The Zone of Exclusion.”

“I’ve got a driver, an old Mercedes, and a minder. Anything else I need?” I asked Bill, who was already decked out in scrubs.

“A rad detector and an appetite for the bizarre.” Off my puzzled look, Bill just smiled, then looked down at my barely dented omelet: “You gonna finish that?”

The road to Gomel

Yes, this part of Belarus was definitely in Rod Serling’s zipcode. Since its founding at the end of the first millennium AD, Gomel has been attacked, destroyed, occupied, rebuilt, and destroyed again by barbarous Slavic tribal unions, Polish princes, Lithuanian Grand Dukes, and finally “invited” into Catherine the Great’s Russian Empire in 1772. Gomel flourished into the twentieth century but was again ravaged when the Red Army’s “liberation” brought it into The Soviet Federation of Socialist Republics. World War II brought the brutality of Nazi occupation when 80 percent of Gomel’s capital was destroyed. Postwar Belarus bounced back, survived Stalin, and was hopeful of achieving independence during Perestroika, but again tragedy struck with massive contamination from neighboring Ukraine’s Chernobyl disaster.

Belarus finally declared independence in 1990 but it was a republic ruled by Vladimir Putin’s puppet president, Alexander Lukashenko—the last of the old-school ironfisted dictators, whose reign continues to this day.

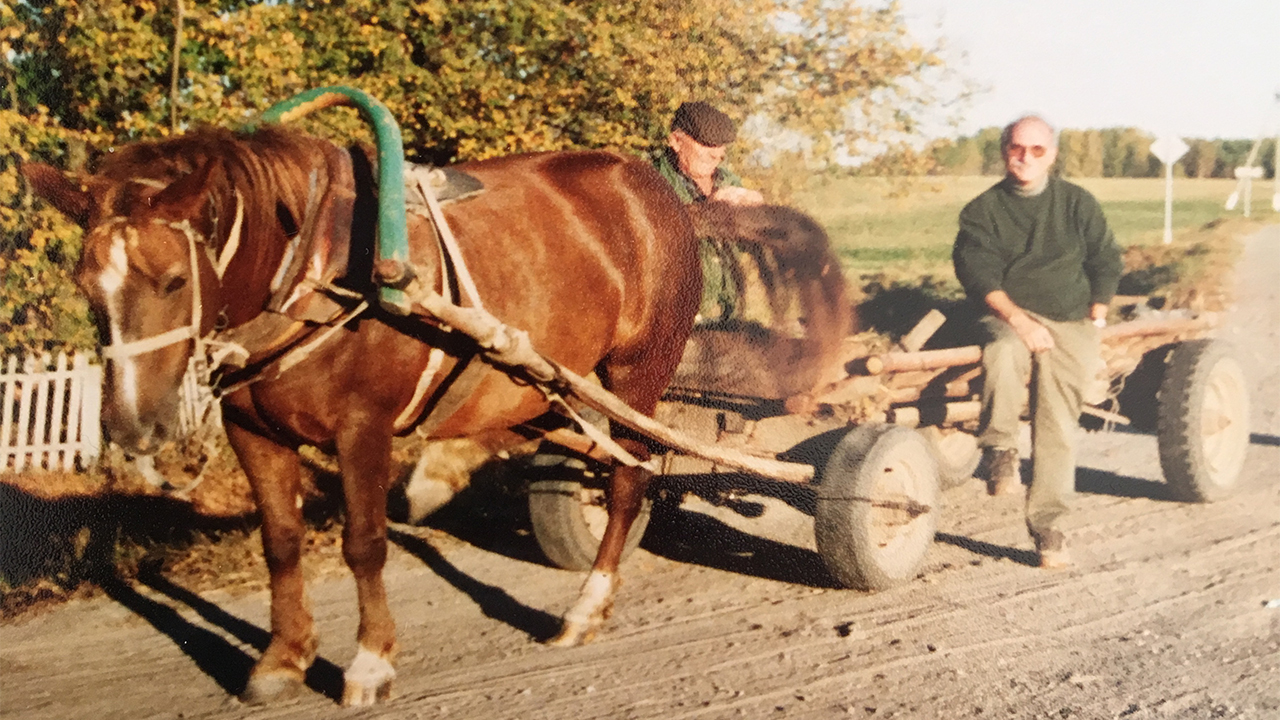

For me that day in 2002 was the beginning of a mashup of Fear and Loathing in Minsk meets Planes, Trains and Oxcarts as I got a guided tour of the no man’s land just across the Pripyat River from the decaying, hulking skeleton of the Chernobyl Reactor Dome. I was shocked to discover a far more chilling story than I bargained for: the reactor’s dome was falling apart—large holes in the ceiling through which pigeons come and go… and the fear that a good thunderstorm could collapse the dome, and accompanying gusts of winds could result in Chernobyl 2.0. A far greater disaster than the original as the reactor house would expel clouds of lethal radiation that would cover most of Europe.

My all-access backstage pass to “The Zone of Exclusion” led me through an eerie landscape of villages so radiated they have been buried and covered over with sand… a lone elderly survivor whose shack has miraculously escaped destruction described the aftermath of the deadly clouds that blew over Belarus: “Buses came in and took away all my neighbors… then the Liquidators (first responders) in their spacesuits… they shot all the dogs and pigs and chickens and buried them along with the whole town. I stayed. I survived Hitler… Stalin… They told me I would die if I remained. But I’m still here. Maybe I’m dead already.”

Before getting on the road, Dr. Bill had pulled me aside and warned me not to eat anything while in “The Zone.” So what would I do when invited for a lunch in my honor by a veteran firefighter and his cherubic wife who had spent half their monthly pension laying out a spread of smoked meats, fish, pickled delicacies… even caviar?

Let us just say that after three shots of Moldavian vodka, my comfort zone had expanded considerably. The festive atmosphere darkened with my host’s vivid descriptions of standing atop the smoldering reactor dome armed with a simple hose. Most of his fellow liquidators died young, with the bitter irony that Belarus got hit far worse than the reactor’s home country of Ukraine:

Seventy percent of the radioactive fallout landed in Belarus, heavily contaminating one-fourth of the country, one-fifth of its agricultural land—ultimately affecting 7 million people, 500,000 having relocated since 1986. Under Lukashenko’s despotic regime these figures were kept secret for decades. I witnessed the Belarussian collective paranoia as the Deputy Mayor of Gomel popped open a Polish vodka and poured some welcoming shots: “ First we find out who you are…” He poured again: “Then we find out what you’re doing here…” And with the third full shot: “And then… we find out who you really are!” Amid gales of laughter, I caught my driver’s eyes, urgently signaling it was time to hit the road.

My screenplay took on a new human dimension as I returned to Minsk and came face to face with the grim legacy of Chernobyl: I joined the surgical team as they performed complex open-heart surgery on the next generations who’ve been cursed with congenital disorders: I watched Dr. Bill perform miracles… experienced his explosive frustration when he lost a two-year-old: “I worked on him for five hours. I brought him back twice. Even shot ice water, an old trick I learned in Med School… but the little f—er checked out on me.”

There would be more life, mostly, thank God, and a few lost causes… grateful, sobbing parents… laugh-out-loud moments in the operating theater, which by now had become old hat to me as I got a crash course in pediatric cardiac surgery performed by all-star medicos. There were also mind-soul bending moments: the perfusionist is a medical technician whose job it is to drain all the blood from the heart and keep it circulating on his machine while the surgeon works on the heart. I witnessed the moment when the child’s life was literally passed over to him… in his care until the procedure was done… and then he flipped the switch and the blood was sent back into the heart—restoring life in a magical moment celebrated with high-fives by all.

In addition to teaching screenwriting at WashU, I was working on a television pilot with Sandra Bullock. This was my “operating theater” and a conference call was scheduled between me in Minsk, my writing partner in the Hollywood Hills, Sandra Bullock in her office, and a CAA agent “not-to-be-named” later in Beverly Hills.

Another surgery highlight came when I finally paid attention to the rock music the team used as a soundtrack to their operations. It was during a sensitive moment when Dr. Bill had to connect a thin PVC-like tube to a tiny ventricle. I could not believe the song that wafted over this dramatic scene: Bob Dylan… Knock, knock, knocking on heaven’s door. If I wrote that in a screenplay you would say, “Aww come on,” but here it was plain as day. I was about to point out the significance to the surgical nurse, but contained my enthusiasm, realizing it might be a dangerous distraction. The anesthesiologist, who had time on his hands, caught my eye and nodded—he, too was aware of this magical music cue and we shared the moment.

After a tear-inducing scene like this, I returned to The Hotel Planeta, for the most bizarre moment of my entire trip. And it did not come from life and death rescues… or the giddy paranoia of being followed and watched in my real-life spy fantasy… It came from… Hollywood.

At this time, in addition to teaching screenwriting at WashU, I was working on a television pilot with Sandra Bullock. This was my “operating theater” and a conference call was scheduled between me in Minsk, my writing partner in the Hollywood Hills, Sandra Bullock in her office, and a CAA agent “not-to-be-named” later in Beverly Hills. The international connection was crystal clear but I noticed there were a lot of clicks and an occasional buzz on the line. We were pitching jokes and “what-iffing” storylines when I had another “Dylan Moment”: there must be others listening in. Like the Belarus Intelligence Service, the KGB… certainly our own NSA and probably the CIA. I once again had to contain myself: we were throwing around all sorts of acronyms—CAA, CBS, NBC… we were using terms like agents, plot structure, killer deals… What must the intel guys be making of this code-like jargon? I kept this hilarious observation to myself, not wanting to distract from the life and death moments in a television pitch.

On the plane home I began stitching scenes together for my screenplay:

A bizarre, heartbreaking visit to an orphanage built by Bono’s wife and her Irishwomen where 170 of the “lost children” of Belarus await against-the-odds chances of adoption. They suffer from malnutrition, fetal alcohol syndrome, severe autism, and various crippling birth defects. The Children’s Fund volunteers do their best and my bag of toys collected from WashU students put smiles on their faces and provide a tiny ray of hope—someone cares.

A strange visit to the American Embassy where I meet the U.S. Ambassador to Belarus… a “Maytag Repairman-type” diplomat with virtually nothing to do because the United States is so hated he never gets invited to state dinners by the omnipotent megalomaniacal dictator, Lukashenko. In addition to the ambassador, the rambling embassy mansion, a leftover from Tsarist splendor, has only two other occupants: his assistant, an elegant, well-coiffed career foreign service lady, and a guy in a flannel shirt who looked like a plumber and was never introduced by name. Definitely the resident CIA spook.

I hand the ambassador’s card to the cops and they smile at each other, hitting the jackpot. They mistakenly think I am the U.S. Ambassador to Belarus and the price of the bribe just shot up threefold, leaving my driver shaking his head—it is going to be a very long day with this Amerikanski clown.

The ambassador chats amiably about his days as a Dartmouth history professor and wishes me well on my research assignment for HBO. He suggests that Kevin Costner should play Dr. Bill and then hands me his gold-embossed business card—if I need anything, do not hesitate to call.

His business card will come in handy on our road trip to Gomel when we are pulled over by bribe-seeking cops on the deserted highway outside Minsk. My driver is negotiating the amount when I decide to help him. I hand the ambassador’s card to the cops and they smile at each other, hitting the jackpot. They mistakenly think I am the U.S. Ambassador to Belarus and the price of the bribe just shot up threefold, leaving my driver shaking his head—it is going to be a very long day with this Amerikanski clown.

Epilogue

It took two more years for a French company to come in and pour tons of concrete to reinforce the Chernobyl Reactor Dome and it will be safe for decades to come… if it is not blasted by the Russian tanks currently parked out front.