Frankenstein Meets Climate Change: Monsters of Our Own Making

Taming the monster: Applying Shelley’s lesson to global warming.

October 26, 2018

Mary Shelley started writing Frankenstein just over 200 years ago. It is a brilliant story of warning and caution that has captured the attention of readers ever since, in part because of its relevance during every phase of our technological history. Recently, a great deal has been made about the warning that Frankenstein provides for modern biomedicine and artificial intelligence. Should we give in to our Promethean urges and meddle in the realm of gods? I will follow a different path here and look at climate change, both in the role it played in the writing of Frankenstein, 200 years ago and in the role it plays now, as a monster of our own making.

The topic of climate first comes in with the writing of the book, in 1816. The 18-year-old Mary Godwin was vacationing in Geneva, Switzerland, with her soon-to-be husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, as well as friends Lord Byron and writer-physician John Polidori. Unfortunately, it was not much of a vacation because the weather was terrible: gloomy, dark, rainy, and cold. So, the group of writers decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story, matching the mood of the season. Mary wrote Frankenstein.

The weather throughout western Europe that summer was miserable. Flooding was so bad that several countries established their first meteorology programs to try to understand and forecast future weather. The reason for the bad weather was a very large volcanic eruption, the largest in the past 500 years. In 1815, Mt. Tambora, on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, sent roughly 100 cubic kilometers of tephra—rock and ash—into the atmosphere and devastated the surrounding islands. [Figure 1]

More invisibly but no less dramatically, the eruption changed climate globally by ejecting over 100 million tons of sulfate aerosols, tiny liquid droplets mostly less than a micrometer (a millionth of a meter) in size. These aerosols partially block incoming sunlight, lowering global temperatures and altering atmospheric flow patterns. North Atlantic atmospheric circulation over the summer of 1816 changed so that storm tracks that would normally have missed central Europe were shifted to the south, and recurrent low-pressure air systems brought cold air and heavy and long-lasting rainfall to western and central Europe. [Figure 2] A volcano in Indonesia altered climate around the world, ruining Mary Shelley’s holiday. Lord Byron summed it up well in the start of a poem (Darkness) that he wrote in 1816: “I had a dream, which was not all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish’d.”

The effects were also large on the other side of the Atlantic. The 1816 summer in New England was cold and severe, with widespread crop failures and snows in July and August, leading to the well-known label of “the year without a summer.” The Vermont town of Granby actually disincorporated, and people packed up and left. Many residents of New England and the Mid-Atlantic states left their homes and headed south and west, looking for greener pastures.

As Will Durant allegedly said, “Civilization exists by geologic consent, subject to change without notice.” We have now turned the tables on Will Durant: in our own era, geology occurs through civilization’s consent. Humans are now Earth’s primary agent of geologic change, and this is nowhere better seen than in a part of the world that was central to the story of Frankenstein: the Arctic.

This played an important role in the settling of the United States. Even though the Louisiana Purchase had occurred a dozen years earlier, it was starting in 1816 that the big push westward occurred, and statehoods followed: Indiana in 1816, Illinois in 1818, and Missouri in 1821. A volcano in Indonesia shaped American history. This was not the first time that a volcanic eruption caused significant short-term changes to climate that impacted humans. Large eruptions of sulfate aerosols had previously occurred in Iceland (Laki, 1783), Peru (Huaynaputina, 1600), Vanuatu (Kuwae, 1452), Lombok (Rinjani, 1258), and before. Each of these was associated with drops in temperature, crop failures, famines, plagues, and collapses in government. Each of these has a complex story of human impacts equally as fascinating as that of Tambora. As Will Durant allegedly said, “Civilization exists by geologic consent, subject to change without notice.”

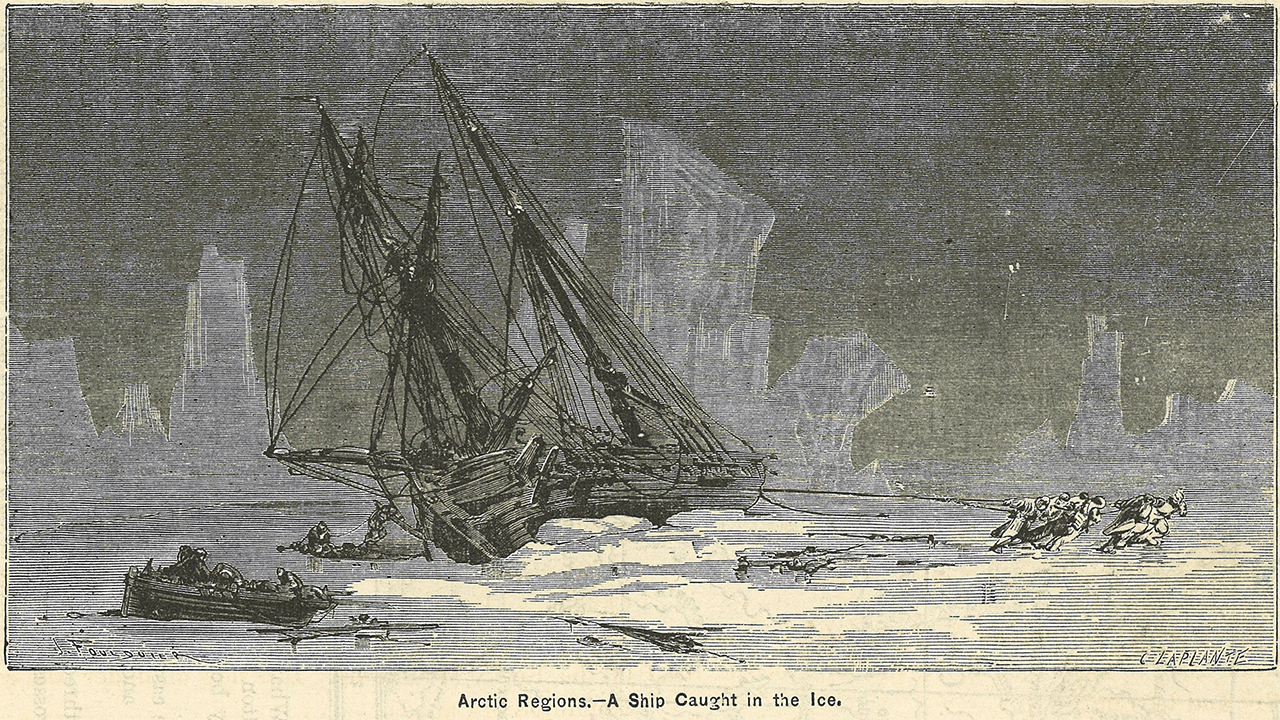

We have now turned the tables on Will Durant: in our own era, geology occurs through civilization’s consent. Humans are now Earth’s primary agent of geologic change, and this is nowhere better seen than in a part of the world that was central to the story of Frankenstein: the Arctic. In 1816, the Arctic Sea was still largely frozen. This was the last phase of the Little Ice Age, a period of decreased solar activity known as the Dalton Solar Minimum. The Arctic Sea remained largely impassible and therefore unknown and unmapped, and there was a lot of attention given to trying to find a Northwest Passage through and across it to the Pacific Ocean. [Figure 3]

Mary Shelley was fascinated with the Arctic. She had heard Samuel Taylor Coleridge recite his Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a poem awash in Arctic references, in the home of her parents. In her teens, she eagerly read accounts of early Arctic voyages. Although the Arctic setting was not in her original draft, she added it after reading about current efforts to drum up support for finding the Northwest Passage.

Two summers ago, I had the pleasure of being the “World Perspectives” lecturer on a National Geographic expedition that sailed from the island of Svalbard, up into the Arctic Circle, and then down the east coast of Greenland. It was a fabulous experience, but also a very sobering one. The ice was gone. [Figure 4] All the ice that used to prevent sailors from reaching the North Pole just was not there. The story of Robert Walton, the ship captain who recorded Victor Frankenstein’s tale while stuck in the Arctic ice, would be unimaginable if Mary Shelley were writing Frankenstein today.

The disappearing ice is part of the powerful trajectory of global warming that began with the Industrial Revolution and has increased ever since. There is no mystery associated with this. It is a direct result of the increasing amount of greenhouse gases that we release into the atmosphere, now more than 9 billion tons of carbon each year. We understand the physics of the greenhouse effect, and the increase in temperatures directly tracks the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide content. [Figure 5]

The year 2015 was the warmest year on record, until 2016 beat it the following year. Although most people are aware of the recent increases in global temperature, most are not aware of how unprecedented the current rate of warming is. Until the nineteenth century, temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere had slowly dropped almost 1 °C, passing through the “Medieval Warm Period” and into the Little Ice Age. Many sources have described the dramatic changes in regional climates over this transition, as well as the often-brutal impacts on civilization. We have reversed this in just one century. Over the past 12,000 years, spanning the entire “Interglacial” period that followed the most recent Ice Age, temperatures had generally been cooling since a peak about 7000-7500 years ago, but we have more than erased this with the warming of the past century, and temperatures are now increasing at a rate never before seen in the geologic record.

The year 2015 was the warmest year on record, until 2016 beat it the following year. Although most people are aware of the recent increases in global temperature, most are not aware of how unprecedented the current rate of warming is. Until the nineteenth century, temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere had slowly dropped almost 1 °C, passing through the “Medieval Warm Period” and into the Little Ice Age. Many sources have described the dramatic changes in regional climates over this transition, as well as the often-brutal impacts upon civilization. We have reversed this in just one century.

The impacts of this warming have been huge. Glaciers around the world are melting at alarming rates. Together, Greenland and Antarctica now melt about 400 billion tons of ice per year. Combined with the warming and expansion of ocean water, this is now making sea levels rise at accelerating rates. The global average of sea-level rise is now about 4.0 mm/year. When I began teaching at Washington University in 1991, it was about 2.4 mm/yr. Not only is the sea level rising, but the rate of sea-level rise is rising. About 40 percent of the world’s population lives within 60 miles of a coastline, and nearly all of the world’s major cities are also major seaports. The last time there were over 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere (it is now 407 ppm and rising rapidly) global sea levels were 75-100 feet higher than today. This is where the Earth system will eventually go, and it is only because it takes a lot of energy to melt ice and to heat (and expand) seawater that this will not happen in our lifetimes.

It is important for us to accept that these recent changes in climate are our own doing. In fact, everything humans now do has a large impact on the planet. “Human impacts,” now a major field of geoscience research, are so great that many geologists discuss how we have brought about an end to the 10,000-year Holocene epoch and begun the new “Anthropocene.”

Personally, I think we are already beyond that. Our impacts may already have ended the 66-million-year Cenozoic Era. We now have our own era—the “Anthropozoic.”

Consider these facts. The total area of paved land in the United States—parking lots and roads—is now greater than the size of the state of Georgia. The area of developed land in the United States (towns and cities) is now greater than the size of California. We now use 40 percent of all continental land to feed ourselves—to raise or grow our food (it is > 50 percent of land in the United States).

The greatest cause of our impacts on Earth comes from our insatiable addiction to energy, which we now use at a rate of over 19 terawatts. For comparison, our planet cools off into space at a rate of 46 terawatts. We consume energy at a planetary scale. It is hard to grasp how much this is. One terawatt equals a trillion watts, or a trillion joules of energy per second. A joule is the amount of energy it takes to lift a 0.1-kilogram object (such as a small apple) up one meter. So, 19 terawatts equal 19 trillion apples lifted one meter, each second, continuously. If humans had to generate their own power, 19 terawatts would be equivalent to each man, woman, and child on the planet bench-pressing about 580 pounds, each second, continuously. For Americans, because they use more than their global share of energy, the amount would be even greater: approximately 2500 pounds each second. The majority of this energy comes from the combustion of fossil fuels, and it is the resulting release of carbon dioxide from this combustion that has powered global warming. Imagine what will happen in coming years, as our human population of 7.5 billion keeps growing and the level of development increases across countries.

Victor Frankenstein makes a creature and then abandons it. In response, the creature exacts revenge on him and his friends and family. The monster gives Victor multiple opportunities to acknowledge him, but still Victor flees and denies him. By the end of the novel, there is some doubt as to who the greater “monster” is, Victor or his creation. By analogy, humans may be the monsters for the inhumane ways in which we treat our planet.

This is not to deny progress on other fronts. When I was born, more than half of the world’s 3 billion people were illiterate and lived in extreme poverty. Now less than 15 percent of the world’s 7.5 billion are illiterate and less than 10 percent live in extreme poverty. Every day another approximately 300,000 people get access to electricity and clean water, and another approximately 200,000 rise out of extreme poverty.

But these human advancements have enormous consequences for our planet. During 1970-2012, the World Wildlife Fund reports that Earth’s vertebrate animal populations declined by 58 percent. The number of living mammals, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and fish is now only 42 percent of what it was when the EPA was created in 1970. What happens to them in the next 42 years? Will they all be gone? We know why they are dying: harvesting, hunting, habitat destruction, climate change, invasive species, and pollution. The WWF report also shows that more than 1.5 Earth’s worth of bio-resources are needed to supply our appetites. In other words, we are borrowing against our children’s future.

But enough doom and gloom. Frankenstein also contains a message of hope. In the end, a lesson is learned by the young ship captain, Robert Walton. In spite of Victor’s delirious entreaty that Walton continue on to the North Pole at all cost, for pride and glory, Walton does end up listening to the reasonable requests of his men and turns back home. What does this mean for us and our monstrous creation of global warming?

Many of us recognize the future hazards of global warming. The challenge is to get us to do something sufficiently significant about it. Part of the problem is that there is now so much bad news in circulation that most of us are overwhelmed by it. We become numb and tune it out. Perhaps this happened to you, reading the last several paragraphs. It is therefore important to offer examples where positive change is being made. Let us not go into denial, like Victor does.

Instead, let us acknowledge our mistakes and rectify them. “Sin” was originally an old English archery term that meant to miss the mark. If you sinned, you missed the mark; try again. Making mistakes is how we learn, and this applies to our impact on Earth’s climate as well. There are quite a few examples of where we “sinned,” then tried again and got it right:

• NASA scientists predicted that if we did not stop releasing chlorofluorocarbons into the atmosphere, the entire ozone layer would be destroyed by 2060. The world took counter-measures and the winter ozone hole over Antarctica is slowly beginning to close up.

• The health and environmental costs of burning coal have been increasingly recognized, spurring design innovations of wind turbines and solar panels, whose levelized costs are now cheaper than coal-powered electricity. As a result, coal companies are going bankrupt and solar and wind power are increasing by 20-30 percent per year.

• Since 1970, the U.S. population, energy consumption, and miles driven have all risen significantly, but air pollution has decreased by more than two-thirds.

We have the power to make things better if we set our minds to the challenges at hand.

So, how do we take responsibility for global warming? We have to start by teaching our children better. Children are open to new ideas and new challenges, and they are going to inherit the Earth, after all. It gives me great hope that there is a new and innovative way of teaching science that is sweeping our country’s schools called the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). The K-12 NGSS promotes a way of teaching that is centered around having students do the practices of science and engineering instead of memorizing facts about science. Started at the National Academy of Sciences and finished by a group of scientists and educators who worked with twenty-six participating states (half “red” and half “blue”), the NGSS built upon the latest research in not only science but also pedagogy, child psychology, and curriculum design. The NGSS is effective not only in increasing student understanding of science, but also in increasing student enthusiasm, appreciation, and engagement with science. In other words, kids find that science is fun.

The NGSS promotes phenomenon-based learning, which uses big-picture “essential questions” or “design challenges” to provide coherence and relevance for student learning. These “phenomena” provide engaging storylines of understanding that give students a framework for understanding the practices, content, and cross-cutting themes of science. Currently, all but ten U.S. states have either adopted or adapted the NGSS for their schools or are in the process of doing so, involving about 80 percent of U.S. school children. As for embracing the monster of global warming, the NGSS requires about a year’s worth of geoscience content in high school as well as middle school, largely focused on human impacts and climate change. This is a major shift from the old-fashioned biology/chemistry/ physics high school curriculum. An NGSS-designed high school curriculum involves a year each of life science, physical science (combining chemistry and physics), and Earth and space science. Most future U.S. citizens will participate in formal education about the science of climate change and our role in it.

Frankenstein also contains a message of hope. In the end, a lesson is learned by the young ship captain, Robert Walton. In spite of Victor’s delirious entreaty that Walton continue on to the North Pole at all cost, for pride and glory, Walton does end up listening to the reasonable requests of his men and turns back home. What does this mean for us and our monstrous creation of global warming?

The NGSS also focus on the design of solutions to problems such as climate change. Yes, the NGSS address human impacts, pollution, global warming, and impacts to the biosphere. But rather than presenting climate change as a tragic result of societal sins, the NGSS challenge students to analyze, assess, design, and engineer solutions to it. The NGSS have a strong emphasis on socially relevant topics such as information technologies, genetics, and human impacts that let students know how powerful they are (all that Anthropozoic stuff), but in a manner that emphasizes the social responsibility that must come with the geologic power that humans now possess.

Frankenstein serves as a warning to young Victors (and Victorias) everywhere. Modern biomedicine and bioengineering actually do give 22-year-olds the power to play with the rules of life itself and dare to be godlike, but the lesson of Frankenstein is that scientific power must be tempered with social responsibility. We, all of us, are now playing god with our planet, and we are making a mess of it. Still, it is not too late. We can learn the lesson Mary Shelley put forth for us. We do not have to deny our monster, run from it, or feel shame for it. We can learn from Victor’s mistakes, take responsibility for global warming, and work to stop it.

Frankenstein is a tragedy that provides a lesson for us now. Victor was no match for the monster he created, which was bigger, stronger, faster, smarter, and always a step ahead. Perhaps it was a mistake to make the creature in the first place, but having done so, the more serious mistake was for Victor to refuse to take responsibility for his creation. That is one reading of the novel. A different one is that we do not have to continue to make the same mistakes, over and over again. As with Captain Walton, we can choose to turn back.

Frankenstein serves as a warning to young Victors (and Victorias) everywhere. Modern biomedicine and bioengineering actually do give 22-year-olds the power to play with the rules of life itself and dare to be godlike, but the lesson of Frankenstein is that scientific power must be tempered with social responsibility.

We, all of us, are now playing god with our planet, and we are making a mess of it. Still, it is not too late. We can learn the lesson Mary Shelley put forth for us. We do not have to deny our monster, run from it, or feel shame for it. We can learn from Victor’s mistakes, take responsibility for global warming, and work to stop it.

Today’s children will face some serious challenges as they grow up. But I am hopeful. With a K-12 education that embraces environmental earth issues, including climate change and our role in it, they may just make the right choices.