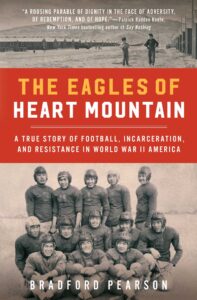

The Eagles of Heart Mountain: A True Story of Football, Incarceration, and Resistance in World War II America

Barreling through the red zone like an oversized running back, a new book blending World War II history and football has scored with surprising flair. The Eagles of Heart Mountain by Bradford Pearson, published in 2021 by Atria Paperback, tells the history of Japanese-American incarceration during World War II through the experiences of several young men from California who went from local athletic heroes to prisoners of war in their own country in shockingly little time. Through powerful firsthand accounts based on primary research and interviews, Pearson provides a stirring narrative of this misunderstood period of American history. He emphasizes football as a form of American cultural expression in which the young men excelled prior to their incarceration. Athletes like George Yoshinaga, Babe Nomura, and Rabbit Shiraki were integral members of their high school teams, receiving praise from the stadium stands and the local press for their exploits on the field. The press coverage could be insensitive at times, with racist headlines such as, “Slit-Eyed Game Ends in Riots,” but it still demonstrated the newsworthy prowess of these young men. After the forced internment at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Cody, Wyoming, football’s importance only grew for the high school-aged prisoners. It became a temporary reprieve from the drudgery of life in the camp, a rare opportunity to reassert one’s humanity, and an acceptable outlet for aggression. The Eagles of Heart Mountain is an engaging entry point into the ugly xenophobia and racism in American society during the Second World War.

Pearson employs a third-person narrative approach to present this history in an engrossing fashion. The text is divided into three sections: the first sets up the key figures and their family histories before Pearl Harbor and U.S. involvement in World War II. The second details the rapid shifts in domestic policy and the formation of internment camps following the Japanese attack on Hawaii. The final section centers on the brief existence of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, using the makeshift football team’s games as a means of characterization and drama.

Pearson emphasizes football as a form of American cultural expression in which the young men excelled prior to their incarceration. Athletes like George Yoshinaga, Babe Nomura, and Rabbit Shiraki were integral members of their high school teams, receiving praise from the stadium stands and the local press for their exploits on the field.

Pearson’s terminology is purposeful, and this review remains consistent with his distinctions. As he writes, the common phrasing of “Japanese internment,” is both an inadequacy and incorrect. The people forced from their homes at this time were, “Americans of Japanese descent,” or, Japanese who “had been in the United States for decades and were barred from naturalization.” (ix) He further clarifies that the term “internment” does not properly encapsulate the treatment of the average Japanese Americans forced into camps like Heart Mountain, and the more accurate phrasing should be “incarceration.” (ix) Internment refers to a much smaller population and form of detention for “enemy aliens during wartime,” but most of those relocated to the War Authority Camps were American citizens. (ix) Pearson acknowledges it is an imperfect solution to use the prison terminology of incarceration, as it implies those inside had committed crimes, but he follows the lead of Japanese-American historians in emphasizing the forced conditions of these camps. These deliberate choices distinguish Pearson’s scholarship and approach to his subject, particularly when the misnomer of “Japanese internment” has become so commonplace. Furthermore, the need to revise the terminology around this period demonstrates that we, as a society, have not properly reckoned with this period of history, and The Eagles of Heart Mountain is an important early corrective step.

The book opens with a powerful first-hand anecdote about sixteen-year-old George Yoshinaga, who was confronted on December 7, 1941, by a White neighbor with the forceful question, “Do you know what your people did?” (3) The native of Mountain View, California, was confused on multiple levels by who “his people” could be, and what had occurred. Pearson uses this personal story to draw the reader into the history of Japanese-American incarceration, and we continue to follow Yoshinaga and several other young athletes throughout the text. The personal characterization invests the reader in the tragic historical events and supports Pearson’s theme that the humanity of those incarcerated in so-called internment camps was stolen. The Eagles of Heart Mountain reasserts their vitality.

In addition to the biographical material of the representative incarcerated individuals, Pearson alternates chapters detailing the ongoing historical events and institutional responses that built on xenophobic regulations to the mass imprisonment of Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. He employs a similar strategy of building a history through individual narratives, though government officials are presented at a greater distance than the Japanese Americans, at the heart of the book. This is representative of both the research methods and the sympathies of the author, as there are more personal family interviews of the primary subjects of the text, and those responsible for their incarceration are rightfully given less consideration. Early in Part One, Pearson provides background on General John DeWitt, one of the key architects of the concentration camps. The author demonstrates through his biography that DeWitt, “was a bureaucrat in the most derisive definition of the word. His indecisiveness bred paranoia and anxiety, a cluster of traits no one wants to define its military leaders.” (84) The author’s editorializing is justified through the historical evidence he provides in these informative early chapters.

What sets The Eagles of Heart Mountain apart from other histories of this period is Pearson’s emphasis on football as a cultural signifier. The athletic prowess of young men such as George Yoshinaga, Babe Nomura, and Rabbit Shiraki are presented early in the book as emblematic of the assimilation of second-generation Japanese Americans. Yet despite playing pivotal roles on their high school teams, their marginalization as token Japanese players on largely White teams foreshadows the rapidity with which they are removed from society in early 1942. Football ultimately becomes a source of pride and an outlet for contained aggressive revenge, as the makeshift high school team at Heart Mountain posts dominant wins over the local competition in Wyoming. Pearson’s prose in these sections shifts from somber historian to rousing sportswriter as he transports us to the sidelines of the Eagles gridiron. Of a pivotal game near the end of Heart Mountain’s season, Pearson recounts, “So Rabbit did the second-best thing rabbits do: he ran as fast as he could. He ran past his own stunned teammates. Then he ran past Afferbach. Then he ran past the best athlete in the state. He ran 60 yards, and when he was done, the Eagles were heading into half-time down just 19-13.” (277) The excitement that follows the journey of the Heart Mountain Eagles from game to game propels the larger historical narrative of the incarcerated Japanese Americans with the urgency of a last-minute drive toward the end zone. The imprisoned teenagers at the center of this story are not victims or alien beings, but strong human beings capable of matching any local high school at a sport that was a central cultural signifier of local and national pride.

Pearson’s research is impressive for a text not published by an academic press. He includes sixty-six pages of end notes demonstrating the myriad of sources that comprised the information within The Eagles of Heart Mountain. Much of the information included comes from primary sources of family interviews and archives, along with archival materials from the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, local municipal archives, government, and military records. This is supplemented by secondary materials such as the self-published camp newspapers Heart Mountain Sentinel and Echoes, local sports journalism, and existing scholarship on Japanese immigration, Pearl Harbor, World War II, and the incarceration camps. This rich conglomeration of evidence allows Pearson to write an authoritative history of Japanese-American incarceration through the lens of the Heart Mountain Eagles football team.

The excitement that follows the journey of the Heart Mountain Eagles from game to game propels the larger historical narrative of the incarcerated Japanese Americans with the urgency of a last-minute drive toward the end zone. The imprisoned teenagers at the center of this story are not victims or alien beings, but strong human beings capable of matching any local high school at a sport that was a central cultural signifier of local and national pride.

The Eagles of Heart Mountain is an impressive study of the concentration camps that imprisoned over one hundred thousand Japanese Americans during World War II. The engrossing narrative of several prominent athletes gives Pearson a springboard from which to recount this disturbing history of wartime incarceration. This is by no means the only history of the Japanese concentration camps, but it is unique in its focus on the Heart Mountain facility of Wyoming and its emphasis on the role of football to provide some joy and self-expression for some of those imprisoned. Football fans seeking a novel tale of a forgotten underdog may be enlightened by the historical context that remains understudied, and those familiar with domestic history during World War II will find engrossing new insights through the exploits of the young athletes of Heart Mountain. The Eagles of Heart Mountain is an essential reminder of the resiliency of human collectives when faced with dire adversity. Much like those heroic players, this book is a winner.