Gurgaon in plain sight is a dismal city near New Delhi, India’s self-absorbed capital. Flanking a national highway and hedged on one side by a forest of hardy shrubs, Gurgaon lies in a suburban sprawl that has no center even though there are several buildings that proclaim ‘City Center.’ Builders claim it is ‘modern,’ but what they mean is new. Its inhabitants do not know the names of most of its roads. They too are new, chiefly seniors who have fled Delhi and young couples from all over of the nation who work in the corporations that have set up offices in Gurgaon. Just a few years ago, a different kind of people used to live in Gurgaon leading a very different life. They were farmers who used to grow grain, millets and mustards. Then the builders made them offers they could not refuse. Hectares of land were sold to the builders transforming villagers into sudden millionaires. They went with bags filled with cash to buy cars. They started businesses, many became land brokers. Their diet changed, habits changed. As one of them told me, about seven years ago when the transformation was still fresh, they were introduced to “heart attack.” They bought fancy villas. A resident of one of Gurgaon’s villas, the wife of a retired railway officer, told me that one day she saw a woman at her gates. “I thought she wanted a job as a maid but then I realized she wanted to buy a house.”

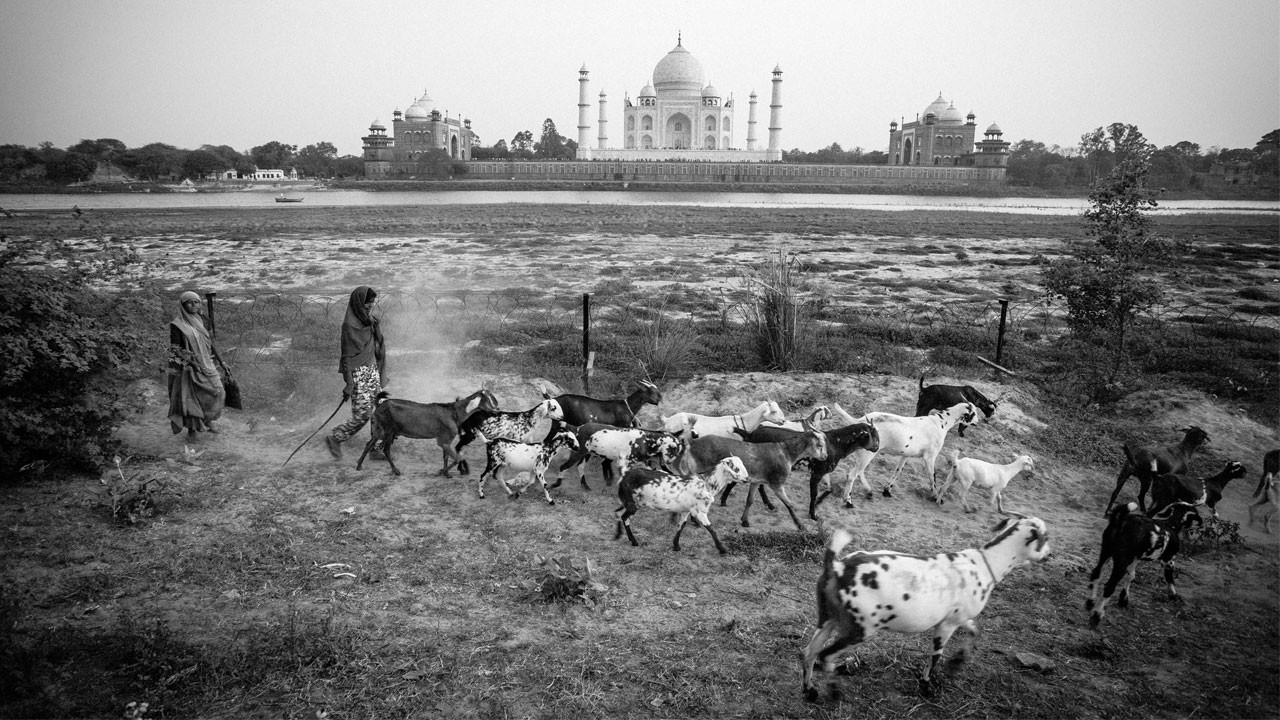

Farmers have not entirely vanished from Gurgaon, but they have retreated into the ever-receding margins where they live on small farms with ever-masticating camels and cows. They await the builders. That is what agriculture in India is today—land awaiting the builders, farms waiting to become real estate.

The productivity of Indian agricultural land has improved vastly over the decades but it lags far behind not just developed economies but also other middle-income countries. India’s rice productivity per hectare is half of that of China’s, and its wheat productivity is less than 60 percent. About half of India’s population is employed in agriculture or associated industries, but contributes less than 20 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. But India is vast, and more than 60 percent of its land is used for agriculture. Only the United States has more arable land than India. As a result India is a statistical giant in farm produce. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, Indian agricultural exports in the decade between 2003 and 2013 grew faster than those of any other nation. India is among the largest producers of several crops. India can feed all its people and more. In fact, one of its major problems is that huge quantities of grains that are meant for the poor rot in warehouses.

So, the question that Indians with socialistic leanings—nationalists, traditionalists and others who are suspicious of science and foreign corporations—ask is why India should bother at all with the seemingly risky genetically modified crops. Isn’t all well as things are?

India has consistently demonstrated its will to stand up to the whole world to protect the commercial interests of the farmer, who is politically crucial.

Genetically modified crops have better yields, are more resistant to conventional pests than organic crops, and use less fertilizer. India permits the use of genetically modified seeds only in cotton cultivation. Since 2002, when the technology was allowed, India’s otherwise doomed cotton production increased many folds and the nation is today one of the major cotton producers in the world. But the technology has also been mired in controversy with activists alleging that seed companies, chiefly Monsanto, which produces Bt Cotton, have exaggerated the benefits and played down the reverses. They have accused Monsanto of being responsible for farmers falling into debt traps, and for their suicides. Several independent studies have disproved this hypothesis but the issue has become a matter of belief. Years of campaign against the technology by both honest and spurious activists, and the tendency of Indian journalists who cover rural affairs to be suspicious of multi-national corporations, have instilled the fear in the minds of farmers that the products of biotechnology would make them beholden to seed companies like Monsanto.

The fact is that India has an exemplary law in place that protects the Indian farmer from becoming a slave to the monopoly of private corporations. Also, India has consistently demonstrated its will to stand up to the whole world to protect the commercial interests of the farmer, who is politically crucial. Yet, Indian politicians, who are usually practical men of the world, as a result short-term players, see no immediate gain in risking the wrath of farmers, activists and nationalists.

• • •

In May this year, after the new government was sworn in, India’s agriculture minister, Radha Mohan Singh, said on his first day in office, “I have spoken to government officials and feel GM technology is important.” But he added, “If it is very essential then we will implement it.”

The Bharatiya Janata Party, which was triumphant in the general elections held this year, had maintained through out its campaign that it would permit genetically modified crops only after serious scientific evaluation in Indian conditions. It was an admirable stand but the new government, like its predecessors, has succumbed to the pressures of activists and put on hold its valiant plans to understand the technology better from a purely scientific point of view. There is a case for India to be circumspect, but it has done nothing to comprehend its own circumspection and to make an informed decision. Instead, the Indian government has yielded to the threats and campaigns of activists.

There are several reasons why there is an urgent need for India to overhaul its agriculture through modern technology, bio-technology being just one of the many sciences it must prospect.

Farming is venerated in India, chiefly by those who are not farmers. An overwhelming majority of India’s farmers are unable to share this quaint adoration because they are impoverished. Working on an Indian farm is among the least paying jobs in India. Not surprisingly, the aspiration of young rural Indians is to find liberation from farming. In fact, it is the lack of good opportunities in agriculture that is driving millions of young Indians to seek their future in the cities, where they live in inhuman conditions. Skilled farm workers are arriving in cities to become unskilled security guards in para-military uniforms, who are so malnourished even stray dogs taunt them. They also become drivers, gardeners, and maids. The educated are luckier but they struggle against the more sophisticated urban graduates. Many of India’s social problems and urban nightmares emerge from the crushing poverty meted out by India’s agricultural sector to its own.

States like Punjab and Maharashtra have shown that increasing the productivity of its agricultural land and the associated industries such a growth would create can transform societies within the lifespan of a government. Biotechnology is not the answer, but it is a part of it. For instance, Indian agriculture is a perennial victim of the extreme forces of nature. India is constantly hit by droughts and floods, and by pests. The Indian government has an unambiguous humanitarian reason to investigate whether biotechnology can solve some of the nation’s unique problems. If India can create crops that can withstand droughts and floods, it would be an achievement that is far greater than sending a color camera to orbit Mars.

In February of last year, Manmohan Singh, in his final weeks as prime minister said, “Use of biotechnology has great potential to improve yields. While safety must be ensured, we should not succumb to unscientific prejudices against” genetically modified crops.

But it appears that he could not convince his own government to adopt the technology. Genetic Engineering Approval Committee (GEAC), which has the mandate to regulate the development and cultivation of genetically modified organisms in India, had cleared several GM crops for field trial in 2013, but the minister of environment and forest, Jayanthi Natarajan put them on hold. She was replaced by a man who claimed that she had misread a court directive. He approved the trials. But in May, after the general elections, the government headed by Manmohan Singh ceased to exist, and a new government headed by prime minister Narendra Modi was sworn in. In July, the Approval Committee, cleared thirteen crops for field trial, but a few days later the government put the trials on hold. The turnabout was influenced by objections raised by two outfits, one of whose philosophy is to reject, “materialistic and imperialistic homogenisation (sic) and aimless transnationalism of the Western assumption”; and the goal of the other outfit is, “to collect, experiment, innovate, improve and publicise (sic) the centuries old practices and usages in the agriculture field …”

It is not hard to comprehend the nature of the opposition to biotechnology in India.

The current Indian government is not opposed to genetically modified organisms. Nor was the government that it replaced. Their reluctance cannot be attributed to scientific scrutiny or concern for the commercial wellbeing of its farmers or the health of its citizens.

In almost every sphere of life, India shows no regard for the welfare of its citizens. Indian cities are among the most polluted in the world. Vehicles that are long dead are allowed to ply on the road. Children travel to school in open rickshaws, a dozen crammed into one that can fit only four. Several die in accidents on the way to school or on their way back. Chemical factories have very poor safety precautions. Buildings collapse because they have been built on loose soil or with poor material. Almost every restaurant is a serious fire hazard. Poorly designed roads, as much as wild driving, cause hundreds of fatalities every day. In Mumbai’s suburban trains, men dangle from the doorways because those trains do not have automatic doors—hundreds die every year by falling. Yet, it is possible that such a nation would be concerned about the health implications of a technology even if developed economies have deemed safe for their citizens. Such a concern would have been honorable, even touching. But then the fact is that India’s biotech policy has been disproportionately influenced by a mob of urban and provincial elites who hold on to traditions to sustain their own relevance in a changing world.

The two outfits that coerced the government to put the trials of genetically modified crops on hold—Swadeshi Jagran Manch and Bharatiya Kisan Sangh—are affiliated to the Hindu nationalistic Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the ideological mothership of the party that governs India today. The RSS, in Indian public conscience, is a fellowship of adult males in billowing khaki shorts and shirts, who perform morning drills in rudimentary physical exercise. Membership is not open to women. The stated purpose of the organization is to preserve and promote India’s Hindu ideology. It is a society of fierce intellectuals, academics, writers and thugs, which is despised by the nation’s westernized liberals. But the requirements of activism have brought together the fellowship of male ideologues and urban liberals, among them “eco-feminists,” whatever that might be, on the same side in the battle against GMOs.

The aristocracy of these liberals are the village romantics. They are usually affluent, western educated, city-dwellers who are the beneficiaries of hailing from the top layers of India’s social hierarchy. They inherited not just wealth, but also class, privileged education, social contacts and other forms of exceptional advantages that ensured that they would remain the aristocracy even if the world changed fast. Like Gandhi. He too, unsurprisingly, was a village romantic.

They like the idea of the unchanging Indian village inhabited by colorful unchanging rustics who work on their small organic farms. Yet, what they love is the illusion of the Indian village, a village that does not now exists or ever actually existed. Deep within, the Indian village was a perpetually miserable place. The primary author of the Indian Constitution, B.R. Ambedkar, said six decades ago, “The love of the intellectual Indian for the village community is of course infinite, if not pathetic. … What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow mindedness and communalism?”

Its oppressed have prayed for the village to be transformed. But the village romantics, who live far away in their bungalows, do not like the evolution of the village. They find economic progress, which transforms farms into real estate, visually ugly. They wish everything remained the same, because when everything remains the same they have something beautiful to marvel at from the outside—small, lush fields that are not very productive, good natured rustics who are stranded in their lives, zero-emission bullock carts.

To the western world, the most famous of the contemporary Indian village romantics is Vandana Shiva, who is also among the world’s most prominent activists against genetically modified organisms.

• • •

A recent article in The New Yorker magazine by Michael Specter portrayed her campaign. It is inevitable that a story of this nature would provide Shiva’s perception of India’s Green Revolution that began in the 1960s and transformed Indian agriculture through innovations and the use of fertilizers and pesticides. “Shiva believes that it destroyed India’s traditional way of life,” Specter writes, “She told me that, by shifting the focus of farming from variety to productivity, the Green Revolution actually was responsible for killing Indian farmers. Few people accept that analysis, though, and more than one study has concluded that if India had stuck to its traditional farming methods millions would have starved.”

They [the village romantics] wish everything remained the same, because when everything remains the same they have something beautiful to marvel at from the outside—small, lush fields that are not very productive, good natured rustics who are stranded in their lives, zero-emission bullock carts.

Vandana Shiva is among the Indian intellectuals whom the West looks up to for an interpretation of Indian maladies. There are times when what these people say is so ridiculous to an Indian ear that one wonders if they realize that Indians, too, would be reading their analyses.

Shiva’s imagination of a pastoral paradisiacal India before the Green Revolution is so outrageous it borders on hilarious. Almost all of Indian literature and cinema of an age are essentially about the crushing, numbing poverty on the Indian farm before the Green Revolution began to transform the society. In fact, India was so food deficient before the Revolution that there would be police raids on wedding feasts to check if the guests were being fed too much food.

India paid a price for the advancement, of course, through ecological damage. But generations of Indians would agree with Specter’s analysis that the incontrovertible fact is that the Green Revolution saved millions of Indians from starvation. In a way, the Revolution created India’s vast educated middle class, the progeny of farmers who did not essentially get rich but prospered enough to send their children to schools and colleges, who in turn formed a formidable mass of first generation literates that straddled across metros and small towns, and became the very backbone of modern India.

The New Yorker story seriously challenges the credibility of many of Shiva’s claims, and of Shiva herself. Specter writes, “Shiva said last year that Bt-cotton-seed costs had risen by eight thousand per cent in India since 2002. In fact, the prices of modified seeds, which are regulated by the government, have fallen steadily… Shiva also says that Monsanto’s patents prevent poor people from saving seeds. That is not the case in India. The Farmers’ Rights Act of 2001 guarantees every person the right to “save, use, sow, resow, exchange, share, or sell” his seeds. Most farmers, though, even those with tiny fields, choose to buy newly bred seeds each year, whether genetically engineered or not, because they insure better yields and bigger profits.”

These are vital facts, and Shiva is unable to contest them in her written response to the article. All through her response, which she posted on her website, she adopts the classic activist strategy of appearing to rebut the specific points raised in an article but discussing a range of issues that the story never stated or implied in the first place. Shiva denies that she ever said that the Bt-cotton seed costs had risen by eight thousand percent in India. Then she goes on to show the difference in prices between natural cotton seeds before Monsanto entered the market and Bt, which was not the comparison the article was claiming to make.

Also, the story raises the serious question whether activists like Shiva are, in fact, responsible for the starvation or malnutrition of millions in the world’s poorest nations. By protesting against genetically modified crops that are enriched by vitamins, crops that are developed by non-profits and have been proven to be safe, are they not denying the poor their right to better foods? Shiva’s response does not address this crucial question.

On the plates of India’s poor, when they do find food, there is always a huge portion of grain. Their meals are chiefly mere starch. The free or cheap food that they receive is almost entirely in the form of grains. India has a responsibility to scientifically investigate the genetically modified crops that add nutrition to grains, and clear them for consumption if they are indeed safe. Even if Shiva would raise hell.

More than The New Yorker story it was Shiva’s insubstantial response that indicted her as a person who employs hyperbole to stir the emotions of her western audience. It is an outdated mode of activism. In the age of information, the smartest activists stick to facts.

Her most powerful claim—that Monsanto was responsible for the suicides of indebted farmers in India, and that the company was responsible for “a genocide”—is largely discredited in India’s mainstream news media, which was once instrumental in the wide dissemination of the hysteria when it began. Several independent studies by highly regarded academics have attempted to explain the so-called ‘farmer suicides’ and they have found Shiva’s favorite hypothesis outlandish.

India can yet ban genetically modified life in India, but it should have an honorable reason for doing so.