The secret at the bottom of the whole business is simply this: there is no such thing as a man of genius. I am a man of genius myself, and ought to know. What there is, is a conspiracy to pretend that there are such persons, and a selection of certain suitable individuals to assume the imaginary character. The whole difficulty is to get selected.

On reflection I perceive that this explanation is too straightforward for anyone to understand. Let me try to come at it by another way. You will at least admit that Man, having, as he cynically believes, excellent private reasons for not thinking much of himself, has a praiseworthy desire to improve on himself—an aspiration after better things is what you probably call it. How when a child wants something it has not got, what does it do? It pretends to have it. It gets astride of a walking stick and insists on a general conspiracy to pass that stick off as a horse. When it grows to manhood it gives up pretending that walking sticks are horses, not in the least because it has risen superior to the weakness of conspiring to cherish illusions, but because on leaving the nursery it has passed into a sphere in which real horses are attainable, at which point the pretense becomes unnecessary. The moment it becomes necessary, the pressure which kept all eye closed to its absurdity ceases. Here you have the whole explanation of the fact that the grown man is more “sensible” than the child, or the civilized man than the savage. Because he is able to attain more, he pretends less. With regard to the things that are beyond his attainment, he pretends as arrantly as his 5-year-old boy.

The secret at the bottom of the whole business is simply this: there is no such thing as a man of genius. I am a man of genius myself, and ought to know.

For example, he wants, as aforesaid, to improve on himself. But is such a want possible, seeing that Man, whatever he may suppose to the contrary, most certainly cannot conceive anything that is outside his own experience, and therefore in a sense cannot conceive anything higher than himself, nor desire a thing without conceiving it. But that difficulty is very easily got over. Pray, amiable sir or madam, what is the thing you call yourself? Is it yourself as you are with people you like or as you are with people who rub you the wrong way? Is it yourself before dinner or after it? Is it yourself saying your prayers or driving a bargain, listening to a Beethoven symphony of being hustled by a policeman to make way for a public procession, buying a present for your first love or paying your taxes, fascinating everyone in your best clothes or hiding your slippers and curl papers from the public eye? If your enemy might select some one moment of your life to judge you by, would you not come out mean, ugly, cowardly, vulgar, sensual, even though you be another Goethe; or if you might choose the moment yourself, would you not come out generous and handsome, though you may be, on average of all your moments, a most miserly and repulsive person? At worst, you are brave when there is no danger, and openhanded when you are not asked for anything, as one may see by your sympathy with the heroes of your favorite novels and plays.

Our experience does, then, provide us with material for a concept of the superhuman person. You have only to imagine someone always as good as you were in the very loftiest 10 seconds of your life, always as brave as you felt when you read The Three Musketeers, always as wise at a moment’s notice as the books into which philosophers have garnered the corrected errors of their lifetime, always as selfless as you have felt in your hour of utmost satiety, always as beautiful and noble as your wife or husband appeared to you at the climax of the infatuation which led you to the matrimonial experiment which you may or may not have regretted ever since, and there you have your poet, your hero, your Cleopatra or whatever else you may require in the superhuman line, by a simple rearrangement of your own experience, much of which was itself arrived at by the same process.

Wise indeed and wisest among men would be he who could now say to me: Why should I deceive myself thus foolishly? Why not fix my affections, my hopes, my enthusiasms on men and women as they are, varying from day to day, and but rarely seeing the highest heaven through the clouds, instead of on these ideal monsters who never existed and never will exist, and for whose sake men and women now despise one another and make the earth ridiculous with Pessimism, which is the inevitable end of all Idealism? But the average man is not yet wise: he will have his ideals just as the child will have his walking stick horse. And the lower he is, the more extravagant are his demands. Everyone has noticed how severely fastidious a thoroughpaced blackguard is about the character and conduct of the woman to whom he proposes to confide the honor of his name, whereas your great man scandalizes his acquaintances by his tolerance of publicans and sinners. Again, if you are a dramatist writing plays for a theatre in a disreputable quarter, where every boy in the gallery is a pickpocket, your hero must be positively singing like a kettle with ebullient honesty, a thing which no law-abiding audience could bear for half an hour.

Observe now that the actor who plays to the thieves’ gallery is not really an outrageously honest man: he only lends himself to the desire of the audience to pretend that he is. But do not therefore conclude that he enjoys his position through no merit of his own. If that were so, why should he, and not the “extra gentleman” who silently carries a banner, and who vehemently covets his salary and his place in the cast, be the hero of the play? Clearly because of the superior art with which the hero is able to lend himself to the conspiracy. The audience craves intensely for every additional quarter inch of depth of belief in their illusion, and for every quarter inch they will pay solid money; whilst they will no less feelingly avoid the actor who fails to bear it out, or who, worse still, destroys it. Therefore the actor, though he may not have the merit they ascribe to him, has the merit of counterfeiting it well; and in this, as in all other things, it takes as Dumas fil well said, “a great deal of merit to make even a small success.” But that is only because the competition for leading parts is so tremendous in the modern world. The public is not exacting: it will choose the better of two actors for its hero when it has any choice; but it will have its hero anyhow, even when the best actor is a very bad one, as he often is.

… if you are a dramatist writing plays for a theatre in a disreputable quarter, where every boy in the gallery is a pickpocket, your hero must be positively singing like a kettle with ebullient honesty, a thing which no law-abiding audience could bear for half an hour.

Now let us go from the microcosm to the macrocosm—from the cheap theatre to Shakespeare’s great stage of “all the world,” which, also, be it observed, has its thieves’ gallery. On that stage there are many parts to be cast, since the audience will have its ideal king, its President, its statesman, its saint, its hero, its poet, its Helen of Troy, and its man of genius. No one can be these figments; but somebody must act them or the gallery will pull the house down. Napoleon, called on, as a man who had won battles, to case himself for Emperor, grasped the realities of the situation, and, instead of imitating the grasped realities of the situation, and, instead of imitating the ideal Caesar or Charlemagne, took lessons from Talma. Other king’s parts are hereditary: your Romanoff, your Hohenzollern, your Guelph walks through his part at his ease, knowing that with a crown on his head his “How d’ye do?” will enchant everyone with its affability, his three platitudes and a peroration pass for royal eloquence, and his manners and his coat seem in the perfection of taste. The divinity that hedges a king wrecks itself as effectually on a born Republican as on an English court tailor. I have seen a book by an American lady in which the Princess of Wales is ecstatically compared to “a vestal kneeling at some shrine.” In England a judge is as likely as not to be some vulgar promoted advocate who makes coarse jokes over breach-of-promise cases; passes vindictive sentences with sanctimonious unction; and amuses himself off the bench like an ostler. But he is always spoken and written of as a veritable Daniel come to judgment. Mr. Gladstone’s opinions on most social subjects are too childish to be intelligible to the rising generation; and Lord Salisbury makes blunders about the functions of governing bodies which would disqualify him for employment as a vestry clerk: but both gentlemen are highly successful in the parts of eminent statesmen. The fool of the family scrapes through an examination in the Greek testament by the bishop’s chaplain; buttons his collar behind instead of before; and is straightway revered as a holy man. And the policeman, with his club and buttons, represents unspeakable things to the child in the street. The public has invested them all with the attributes of its ideals; and thenceforth the man who betrays the truth about them profanes those ideals and is dealt with accordingly.

It is now plain how to proceed in order to become a man of genius. You must strike the public imagination in such a fashion that they will select you as the incarnation of their ideal of a man of genius. To do this no doubt demands some extraordinary qualities, and sufficient professional industry; but it is by no means necessary to be what the public will pretend that you are. On the contrary, if you believe the possibility of the ideal yourself without being vain enough to fancy that you realize it—if you retire discouraged because you find that you are not a bit like it—if you do not know, as every conjurer knows, that the imagination of the public will make up for all you deficiencies and fight for your complete authenticity as a fanatic fights for his creed, then you will be a failure. “Act well your part: there all honor lies.”

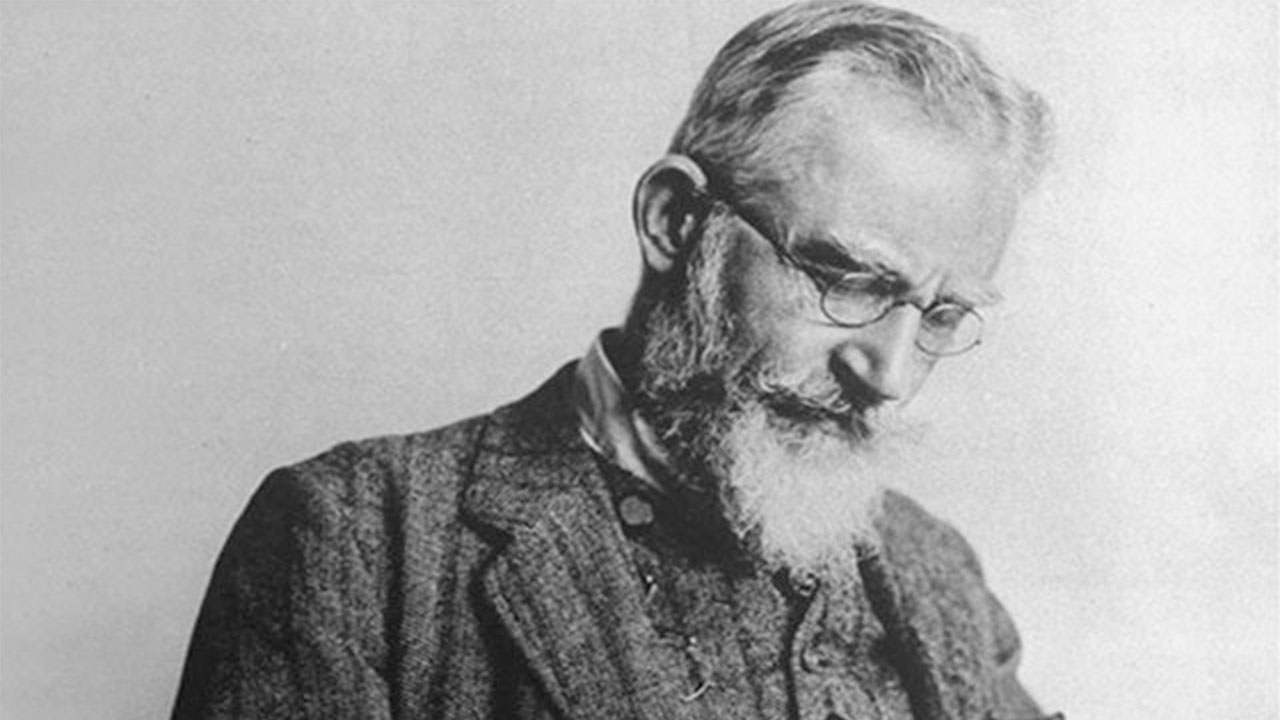

It is possible, however, that circumstances may cast you for such a humble part that it may be difficult even by any extremity of good acting to raise it to an prominence. You must then either be content in obscurity or else do what Sothern did with the part of Lord Dundreary in “Our American Cousin” or what Frederic Lemaître did with the part of Robert Macaire in “L’Auberge des Adrets.” You must throw over the author’s intention and create for yourself a fantastic leading part out of the business designed for a mere walking gentleman or common melodramatic villain. This is the resource to which I myself have been driven. Very recently the production of a play of mine [Arms and the Man] in New York led to the appearance in the New York papers of a host of brilliant critical and biographical studies of a remarkable person called Bernard Shaw. I am supposed to be that person; but I am not. There is no such person; there never was any such person; there never will or can be any such person. You may take my word for this, because I invented him, floated him, advertised him, impersonated him, and am now sitting here in my dingy second floor lodging in a decaying London Square, breakfasting off twopenn’orth of porridge and giving this additional touch to his make-up with my typewriter. My exposure of him will not shake the faith of the public in the least: they will only say “What a cynic he is!”, or perhaps the more sympathetic of them may say, “What a pity he is such a cynic!”

… the time is coming when grown up people will no more cry for their present ideals than they now do for the moon.

It is a mistake, however, to suppose that a man must be either a cynic or an idealist. Both of them have as a common basis of belief the conviction that mankind as it really is is hateful. From this dismal and disabling infidelity the idealist escapes by pretending that men can be trained and preached and cultivated and governed and educated and self-repressed into something quite different from what they really are. The cynic sees that this regeneration is an imposture, and that the selfish and sensual Yahoo remains a Yahoo underneath the scholar’s gown, the priest’s cassock, the judge’s ermine, the soldier’s uniform, the saint’s halo, the royal diadem and the poet’s wreath. But pray where do these idealists and cynics get their fundamental assumption that human nature needs any apology? What is the objection to man as he really is and can become any more than to the solar system as it really is? All that can be said is that men, even when they have done their best possible, cannot be ideally kind, ideally honest, ideally chaste, ideally brave and so on. Well, what does that matter, any more than the equally important fact that they have no eyes in the back of their heads (a most inconvenient arrangement), or that they live a few score years instead of a few thousand? Do fully occupied and healthy people ever cry for the moon, or pretend they have got it under a glass case, or believe that they would be any the better for having it, or sneer at themselves and other people for not having it? Well, the time is coming when grown up people will no more cry for their present ideals than they now do for the moon.

Even the idealist system itself is no proof of any want of veracity on the part of the human race. Moral subjects require some power of thinking: and the ordinary man very seldom think, and finds it so difficult when he tries that he cannot get on without apparatus. Just as he cannot calculate without symbols and measure without a foot rule, so, when he comes to reason deductively, he cannot get on good of anything really existent. The actions of a capitalist as deduced by a political economist, the path of a bullet as deduced by a physicist, do not coincide with the reality, because the reality is the result of many more factors than the economist or physicist is able to take into account with his limited power of thinking. He must simplify the problem if he is to think it at all. And he does this by imagining an ideal capitalist, void of all but mercenary motives, an ideal gun, pointed in an ideal direction with ideal accuracy and charged with ideal gunpowder and an ideal bullet governed in its motion solely by the ideal explosion of the ideal powder and by gravitation. Allow him all these fictions and he can deduce an ideal result for you, which will be contradicted by the first bargain you drive or the first shot you fire, but which is nevertheless the only thinkable result so far.

What is the objection to man as he really is and can become any more than to the solar system as it really is? All that can be said is that men, even when they have done their best possible, cannot be ideally kind, ideally honest, ideally chaste, ideally brave and so on.

Bit by bit we shall get hold of the omitted factors in the calculation, replace the fictitious ones by real ones, and so bring our conclusions nearer to the facts. It is just the same in our attempts to think about morals. We are forced to simplify the problems by dividing men into heroes and villains, women into good women and bad women, conduct into virtue and vice, and character into courage and cowardice, truth and falsehood, purity and licentiousness, and so forth. All that is childish; and sometimes when it comes into action in the form of one man, dressed up as Justice, ordering the slaughter of another man, cased up as Crime, it is sufficiently frightful. Under all circumstances, its pageant of kings, bishops, judges and the rest, is to the eye of the highest intellect about as valid in its pretension to reality as the Lord Mayor’s Show in London is valid in its pretention to dignity. We shall get rid of it all some day. America has already got rid of two of its figures, the king and the subject, which were once esteemed vital parts of the order of nature, and defended with unmeasured devotion and bloodshed, as indeed they still are in many places. The America of today is built on the repudiation of loyalty. The America of tomorrow will be built on the repudiation of virtue. That is the negative side of it. The positive side will be the assertion of real humanity, which is to morality as time and space are to clocks and diagrams.