Orson Welles’s reputation stands on three famous statements, a creaky tripod of words that still prop up his legacy even today.

The first is, of course, “Rosebud!” The loudest whisper in all film history, and also the most famous one-word line in all of film. No other word in the lexicon links childhood dreams to squandered adult aspirations quite like it.

The second is Welles’s self-deprecating remark later in life, when his own adult aspirations failed to materialize. “I started at the top and have been working my way down ever since,” he said.

The third? It must be Welles’s 1970s-era commercial plug for the Paul Masson winery: “We will sell no wine before its time.”

They were the famous last words of the film world’s greatest might-have-been. Welles, the film director and actor who once bestrode the world like a colossus as the 25-year-old prodigy behind “the greatest film ever made” in Citizen Kane, released 1941, had fallen so far that only a mediocre brand of sparkling wine could pay his bills. And conventional wisdom at the time said he had no one but himself to blame. Even if untrue, there is evidence that Welles was not nearly as industrious in his old age as when young, as outtakes of an inebriated old man on the advertising set attest.

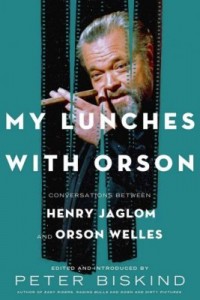

Peter Biskind’s book of transcribed and edited lunch conversations between Welles and younger film director Henry Jaglom, who plays a kind of James Boswell to Welles’s Samuel Johnson, covers terrain from all three Welles-ian landscapes.

Mostly, however, it answers the age-old question: What might a film legend and established Hollywood director talk about when they meet for lunch? If Biskind poses this question in any conscious manner at all, we should remember that tape conversations can be edited for omission, as well as inclusion.

My Lunches With Orson reads almost exactly as you might imagine it, as a kind of Socratic dialogue on life, art, and the manic energy and luck it takes to get a film project off the ground.

Over three years of running tabs at Los Angeles’ Ma Maison restaurant, from 1983 to 1985, the year of Welles’s death, the two run the conversational gauntlet. They talk about film, and sometimes film craft. They kvetch and gossip about other film actors and directors, sometimes mercilessly. “Gielgud used to play Shakespeare as though he were dictating it to his secretary. I told him that myself,” Welles says to Jaglom.

To their great credit, the two criticize each other, and themselves. Jaglom upbraids Welles for his contradictions, his hypocrisy and, most especially, his occasional bigotry toward “ethnic types” in casting film roles.

“I don’t think you’re human if you don’t acknowledge some prejudice,” Welles says to Jaglom, early in their series of lunches. “I don’t need you as my conscience, my Jewish Jiminy Cricket.”

Otherwise, My Lunches With Orson reads almost exactly as you might imagine it, as a kind of Socratic dialogue on life, art, and the manic energy and luck it takes to get a film project off the ground. As noted in the book’s appendix, Welles started, dabbled in, or left incomplete nineteen different film projects before his death. But as Welles’s rabid fans—it is rare to find any other kind—will tell you, that unfinished legacy pales next to the ten completed works he directed and left behind, not to mention such famous film roles as the villainous Harry Lime in Carol Reed’s 1950 film The Third Man.

If we remember Welles more as the director with terminal inability to fund and finish other films, it is only because his talent held a seeming infinite promise.

Jaglom probes Welles’s mind just enough to reveal the man’s shifting focus, and Biskind’s book edits their conversations just enough to lift the veil on perhaps why the famous figure never completed such beloved projects as a complete film version of King Lear, or his political drama The Big Brass Ring.

Character, as Aristotle posited, is action. But it is also in large part the words and thoughts that people dwell on, as Jaglom’s conversations with Welles reveal. Amid brief interruptions from wait staff over cold chicken on a hot plate, cursory glances at a David Hockney painting on the restaurant wall, and even the rank flatulence of a nearby dog, Welles spends too many of his words stirring grudges or wondering why others could not see matters in line with his own. At one point, Welles tells Jaglom to stop plumbing the source of his many antipathies toward people he’s worked with over decades in Hollywood. All that matters is that Welles has them, and they fit him comfortably.

Despite the rancor, readers can appreciate that Welles has style to spare, even when hurling insults at fellow actors.

“I’ve always felt there are three sexes: men, women and actors,” he tells Jaglom. “And actors combine the worst qualities of the other two.”

The only moment where warts overtake wit comes in a business conversation between Welles, Jaglom and an HBO executive curious about the legend’s next big project. The dialogue disintegrates the very second the executive, a woman, apparently changes her demeanor (at least in Welles’s eye) to suggest a change in set location. Welles loses interest, argues, and then refuses to carry on in good faith.

“Wait a minute,” Jaglom says in attempt to salvage the effort of a possible film deal. “Orson, there is a story.”

“There are a lot of stories. But when I get that dead look, I’m dead! I can’t do it,” Welles tells him. “I begin to wonder what I’m talking about. I have to get a little spark from somebody. If I don’t get it, that’s it. I’m lost.”

Fittingly, this entire exchange is in a chapter entitled, “I’m in Terrible Financial Trouble.”

Welles’s Achilles heel, the book shows, isn’t just a fragile, temperamental nature, but incuriosity, a stubborn refusal, to look under the hood for a measure of trouble-shooting and repair. In lunch after lunch, Welles reveals himself only in talking about others. There is no “Rosebud” moment casting the sum of Welles’s parts back to his elemental past. Jaglom reveals his awareness of this, in his words to Biskind in the book’s introduction: “The final scene of The Lady from Shanghai [1947] is perhaps the most autobiographically truthful metaphor in all his work. It is ultimately impossible to find the real Orson Welles among all the fun-house mirrors he so energetically set in place.”

So we settle for mirrors, and other fascinating reflections.

Jaglom has Welles admit without hesitation that all artistic judgments are, at base, subjective. If you thrilled to Welles’s own aesthetic terms across his film output, there is no resisting the temptation to keep track of the director’s personal favorites as part of your own aesthetic scorecard.

He prefers Tolstoy to Dostoevsky, and Mozart to Wagner. Directors John Ford, along with the British filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger—purveyors of lush, color-drenched epics such as Black Narcissus [1947] and The Red Shoes [1948]—are deemed a waste of time.

He loathes Vertigo, Hitchcock’s 1958 masterpiece and the only film yet to unseat Kane as Sight and Sound’s greatest film of all time in a 2012 poll. But it is the famed British director’s Rear Window [1954] that earns his most grating disgust. “Everything is stupid about it,” Welles tells Jaglom.

Buster Keaton soars above Charlie Chaplin, with Welles lavishing the 1926 silent film The General as “The most poetic movie I’ve ever seen.” Almost in passing, he drops the bombshell that it was he, not Chaplin, who wrote the script for Chaplin’s 1947 film Monsieur Verdoux. (Previous credit was given to Welles only for the film’s story-idea.)

Those looking for insights into Welles’s own work and working method will probably be disappointed. He calls Kane a comedy, without elaborating any further, “because the tragic trappings are paranoid.” He tells Jaglom the details of how he maintained additional source footage for every scene shot—“another reel that includes every fragment of what I’ve picked out that might be good”—so that he might always be prepared to mend or improve a bad take later on, when directing has ended and the edit begins.

Otherwise, we get exchange upon exchange of Jaglom indulging, questioning and even interrogating one of the greatest figures in all of film.

“My idea of art—which I do not propose to be universal—is that it must be affirmative,” he tells Jaglom.

“But, wait a minute, Orson, what are you talking about? This is a stupid conversation,” Jaglom replies. “Touch of Evil [1958] is not affirmative.”

The reader can hear the distinctive grain of Welles’s voice in that, and every contentious exchange that follows, in Biskind’s book. It leaves you grateful that Jaglom kept his tape-recorder running during Welles’s interminable blusters of ego, bites of egg-salad sandwich, and tales of his own extravagant life in film.